The Effects of Service Employee Resilience on Emotional Labor: Double-Mediation of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Job Demands–Resources Model

2.2. Emotional Labor

2.3. Resilience

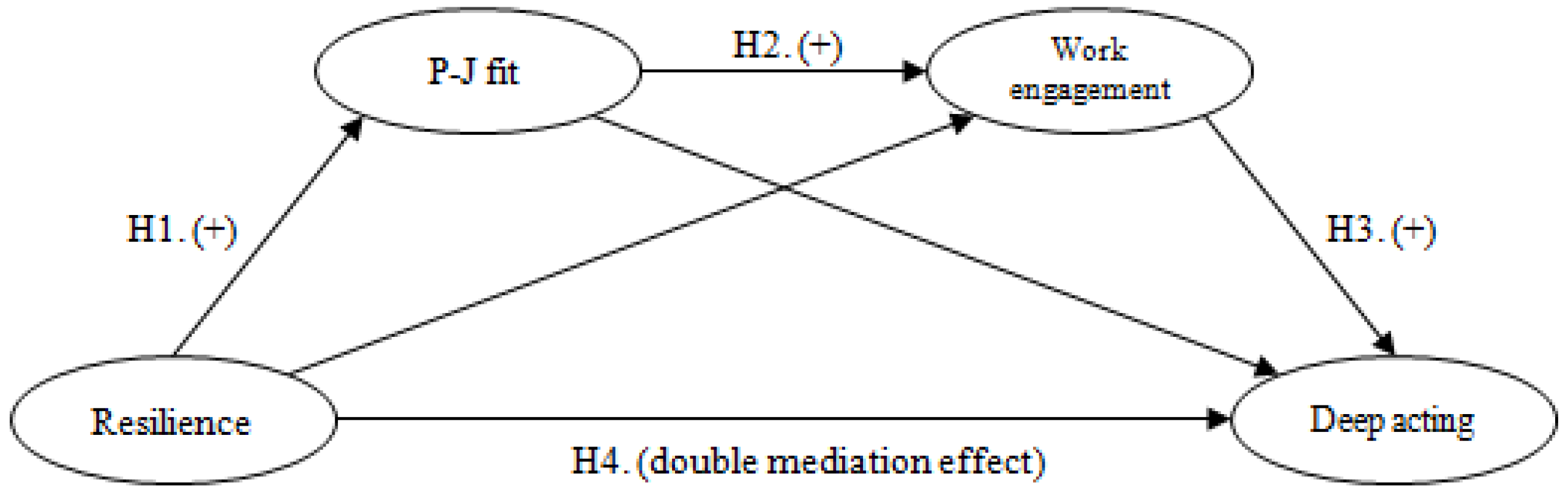

2.4. Resilience and Person–Job Fit

2.5. Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement

2.6. Work Engagement and Deep Acting

2.7. Double-Mediation Effect of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurement of Variables

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity of Constructs

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Double Mediation Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Direction of Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grönroos, C. Service Management and Marketing; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Building Service Relationships: It’s all about Promises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzinikolakis, J.; Crossman, J. Are business academics in Australia experiencing emotional labour? A call for empirical research. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A.; Melloy, R.C. The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.; Arnold, T.J. Frontline employee customer-oriented attitude in the presence of job demands and resources: The influence upon deep and surface acting. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 19, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Han, S.-L.; Hong, S.; Hyun, H. Relationship Bonds and Service Provider’s Emotional Labor: Moderating Effects of Collectivism. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoo, J.J.; Arnold, T.J. Customer orientation, engagement, and developing positive emotional labor. Serv. Ind. J. 2014, 34, 1272–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewig, K.A.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, M.F.; Metzer, J.C. Burnout and connectedness among Australian volunteers: A test of the Job Demands–Resources model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airila, A.; Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.; Luukkonen, R.; Punakallio, A.; Lusa, S. Are job and personal resources associated with work ability 10 years later? The mediating role of work engagement. Work. Stress 2014, 28, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Barrett, L.F. Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1161–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, W.-M.; Rhee, S.-Y.; Ahn, K.-H. Positive psychological capital and emotional labor in Korea: The job demands-resources approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, A. The effect of pre-flight attendants’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and emotional exhaustion on commitment to customer service. Serv. Bus. 2015, 10, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Luo, Y.; Huang, L.; Wen, J.; Ma, J.; Xi, J.-Z. On the relationships of resilience with organizational commitment and burnout: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 30, 2231–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Taylor, M.S.; Seo, M.-G. Resources for Change: The Relationships of Organizational Inducements and Psychological Resilience to Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Organizational Change. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Yen, C.-H.; Tsai, F.C. Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Ashforth, B.E. Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L. Perceived Applicant Fit: Distinguishing between Recruiters’ Perceptions of Person-Job and Person-Organization Fit. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 643–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.E. Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. Am. Psychol. 1983, 38, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastenbroek, N.J.J.M.; Jaarsma, D.A.D.C.; Scherpbier, A.J.J.A.; Van Beukelen, P.; Demerouti, E. The role of personal resources in explaining well-being and performance: A study among young veterinary professionals. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 23, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Johnson, R.J.; Ennis, N.; Jackson, A.P. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Emanuel, F.; Zito, M.; Ghislieri, C.; Colombo, L.; Cortese, C.G. Inbound Call Centers and Emotional Dissonance in the Job Demands—Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miao, C.; Humphrey, R.H.; Qian, S. A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 90, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Rooy, D.L.; Viswesvaran, C. Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, E.E.; Smith, R.S. Vulnerable but Invincible: A Study of Resilient Children; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, E.E.; Smith, R.S. Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children from Birth to Adulthood; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bardoel, E.A.; Pettit, T.M.; De Cieri, H.; McMillan, L. Employee resilience: An emerging challenge for HRM. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2014, 52, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.; Cooper, C.; Sarkar, M.; Curran, T. Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: A systematic review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A.; Coffey, K.A.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S.M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waite, P.J.; Richardson, G.E. Determining the efficacy of resiliency training in the work site. J. Allied Heal. 2004, 33, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Woehr, D.J. A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of Individuals’ Fit at Work: A Meta-Analysis of Person-Job, Person-Organization, Person-Group, and Person-Supervisor Fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Jansen, K.J.; Colbert, A.E. A policy-capturing study of the simultaneous effects of fit with jobs, groups, and organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maden, C.; Kabasakal, H. The simultaneous effects of fit with organizations, jobs and supervisors on major employee outcomes in Turkish banks: Does organizational support matter? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 25, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J. Relationships between various person–environment fit types and employee withdrawal behavior: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Biron, M. Temporal issues in person–organization fit, person–job fit and turnover: The role of leader–member exchange. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 2177–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yoo, J. The influence of social undermining on the service employee’s customer-oriented boundary-spanning behavior. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Derue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scroggins, W.A. An Examination of the Additive Versus Convergent Effects of Employee Perceptions of Fit. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1649–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R.; Schweitzer, M.E. Feeling and Believing: The Influence of Emotion on Trust. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Cultivated Emotions: Parental Socialization of Positive Emotions and Self-Conscious Emotions. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.-Q.; Che, H.; Spector, P.E. Job stress and well-being: An examination from the view of person-environment fit. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Work and Family Stress and Well-Being: An Examination of Person-Environment Fit in the Work and Family Domains. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1999, 77, 85–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisher, C.D. Happiness at Work. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Choi, Y.; Rhee, S.-Y.; Moon, T.W. Social Capital and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Double-Mediation of Emotional Regulation and Job Engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The Impact of Personal Resources and Job Crafting Interventions on Work Engagement and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Kay, V. Resilience as the ability to bounce back from stress: A neglected personal resource? J. Posit. Psychol. 2010, 5, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Han, S.-L. The effects of relationship bonds on bank employees’ psychological responses and boundary-spanning behaviors. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 578–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Ashill, N.J. Service Worker Burnout and Turnover Intentions: Roles of Person-Job Fit, Servant Leadership, and Customer Orientation. Serv. Mark. Q. 2011, 32, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; Van Veldhoven, M. Emotional labour in service work: Psychological flexibility and emotion regulation. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1259–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krush, M.T.; Agnihotri, R.A.J.; Trainor, K.J.; Krishnakumar, S. The salesperson’s ability to bounce back: Examining the moderating role of resiliency on forms of intrarole job conflict and job attitudes, behaviors and performance. Mark. Manag. J. 2013, 23, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Croyle, M.H.; Gosserand, R.H. The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundleby, J.D.; Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1968, 5, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Tein, J.-Y. Tests of the Three-Path Mediated Effect. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld, D.D.; Walker, D.D.; Skarlicki, D.P. The Role of Job Demands and Emotional Exhaustion in the Relationship Between Customer and Employee Incivility. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 507. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, J.; Kaleta, K. Relationships between personality, emotional labor, work engagement and job satisfaction in service professions. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Heal. 2016, 29, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, L.; Salanova, M.; Martínez, I.M.; Vera, M. How personal resources predict work engagement and self-rated performance among construction workers: A social cognitive perspective. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wicks, R.J. Overcoming Secondary Stress in Medical and Nursing Practice: A Guide to Professional Resilience and Personal Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki, M.; Kostistky, H.; Barnoy, D.; Filshtinsky, V.; Bluvstein, I.; Peles-Bortz, A. Exposure of mental health nurses to violence associated with job stress, life satisfaction, staff resilience, and post-traumatic growth. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle While You Work. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, A.; Goel, V. Differential impact of beliefs on valence and arousal. Cogn. Emot. 2013, 27, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and Organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | λ a | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times. | 0.816 | 0.915 | 0.728 | 0.898 |

| It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event. | 0.848 | ||||

| It is not hard for me to snap back when something bad happens. | 0.853 | ||||

| I usually come through difficult times with little trouble. | 0.803 | ||||

| Person–Job Fit | To what extent is the job a good match for you? | 0.773 | 0.876 | 0.638 | 0.852 |

| To what extent does the job fulfill your needs? | 0.794 | ||||

| To what extent do your knowledge, skills, and abilities match the requirement of the job? | 0.774 | ||||

| To what extent does the job enable you to do the kind of work you want to do? | 0.738 | ||||

| Work Engagement | At my work, I feel bursting with energy. | 0.688 | 0.939 | 0.633 | 0.915 |

| At my job, I feel strong and vigorous. | 0.771 | ||||

| When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. | 0.696 | ||||

| I am enthusiastic about my job. | 0.825 | ||||

| My job inspires me. | 0.815 | ||||

| I am proud of the work that I do. | 0.811 | ||||

| I feel happy when I am working intensely. | 0.737 | ||||

| I am immersed in my work. | 0.689 | ||||

| I get carried away when I am working. | 0.602 | ||||

| Deep Acting | I try to actually experience the emotions that I must show to customers. | 0.811 | 0.919 | 0.742 | 0.863 |

| I make an effort to actually feel the emotions that I need to display toward others. | 0.843 | ||||

| I work hard to feel the emotions that I need to show to customers. | 0.808 | ||||

| I work at developing the feelings inside of me that I need to show to customers. | 0.677 |

| Index | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 2.621 | 0.930 | 0.920 | 0.033 | 0.070 |

| Fitting criteria | <3 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.05 | <0.08 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Resilience | 3.187 | 0.797 | 0.853 | |||

| 2. Person–job fit | 3.111 | 0.755 | 0.465 ** | 0.799 | ||

| 3. Work engagement | 3.267 | 0.652 | 0.626 ** | 0.735 ** | 0.796 | |

| 4. Deep acting | 3.632 | 0.633 | 0.358 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.611 ** | 0.861 |

| Path Coefficient | Indirect Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to Person–Job Fit | to Work Engagement | to Deep Acting | Estimate | CIlow | CIhigh | |

| Resilience | 0.3874 ** | 0.3091 ** | −0.0070 | |||

| Person–job fit | 0.4181 ** | 0.0709 | ||||

| Work engagement | 0.4943 ** | |||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.2604 | 0.1917 | 0.3397 | |||

| X→M1→Y | 0.0275 | −0.0157 | 0.0835 | |||

| X→M2→Y | 0.1528 | 0.0920 | 0.2261 | |||

| X→M1→M2→Y | 0.0801 | 0.0474 | 0.1216 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.-S.; Kim, H.-S. The Effects of Service Employee Resilience on Emotional Labor: Double-Mediation of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7198. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197198

Lee M-S, Kim H-S. The Effects of Service Employee Resilience on Emotional Labor: Double-Mediation of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7198. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197198

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Myoung-Soung, and Han-Seong Kim. 2020. "The Effects of Service Employee Resilience on Emotional Labor: Double-Mediation of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7198. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197198

APA StyleLee, M.-S., & Kim, H.-S. (2020). The Effects of Service Employee Resilience on Emotional Labor: Double-Mediation of Person–Job Fit and Work Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7198. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197198