Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Design and Methods

2.1. Overall Study Design

- -

- 2 static lighting conditions that represent typical lighting settings of Japanese (JP) and U.S. offices (i.e., JP-T and US-T conditions);

- -

- 2 dynamic lighting conditions with varying lighting CCT and illuminance (i.e., JP-D and US-D conditions);

- -

- 2 weeks were assigned as the acclimation period at the beginning of this study;

- -

- 1 additional week was assigned to handle the sleep/wake schedule changes due to daylight savings time.

- -

- Condition 1 (JP-T) represented typical lighting conditions in Japanese offices, i.e., 500 lux/5000 K at the horizontal desk level.

- -

- Condition 2 (JP-D) was the dynamic lighting profile for Japanese offices. It varied in reasonable Japanese lighting ranges, i.e., the illuminance falls between 500 and 700 lux and CCT falls between 3500 and 6000 K.

- -

- Condition 3 (US-T) represented typical lighting conditions in US offices, i.e., 300 lux/4000 K.

- -

- Condition 4 (US-D) was the dynamic lighting profile for U.S. offices. It varied in reasonable U.S. lighting ranges, i.e., the illuminance falls between 300 and 500 lux and CCT falls between 3000 and 5000 K.

- -

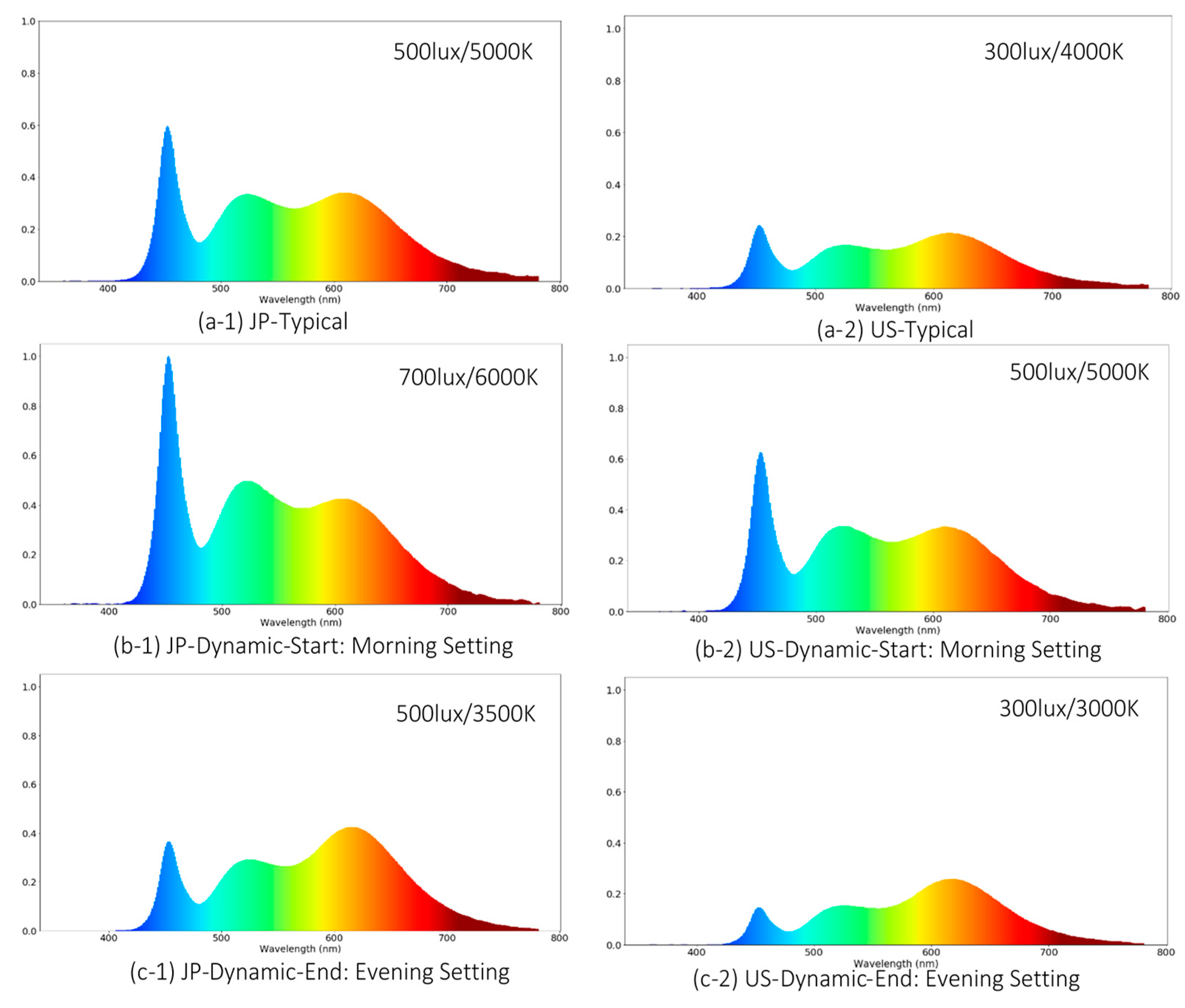

- Dynamic lighting profiles (i.e., JP-D and US-D) presented increased illuminance and CCT levels in the morning compared to the corresponding static lighting level.

- -

- Dynamic lighting profiles presented gradually decreased illuminance and CCT levels in the afternoon to mimic the natural daylighting variations

- -

- JP-D and US-D shared the same magnitude in illuminance variation, i.e., to present a constant shift between them over time

- -

- JP-D and US-D shared the same CCT variation trends that can create similar recognized color change over time.

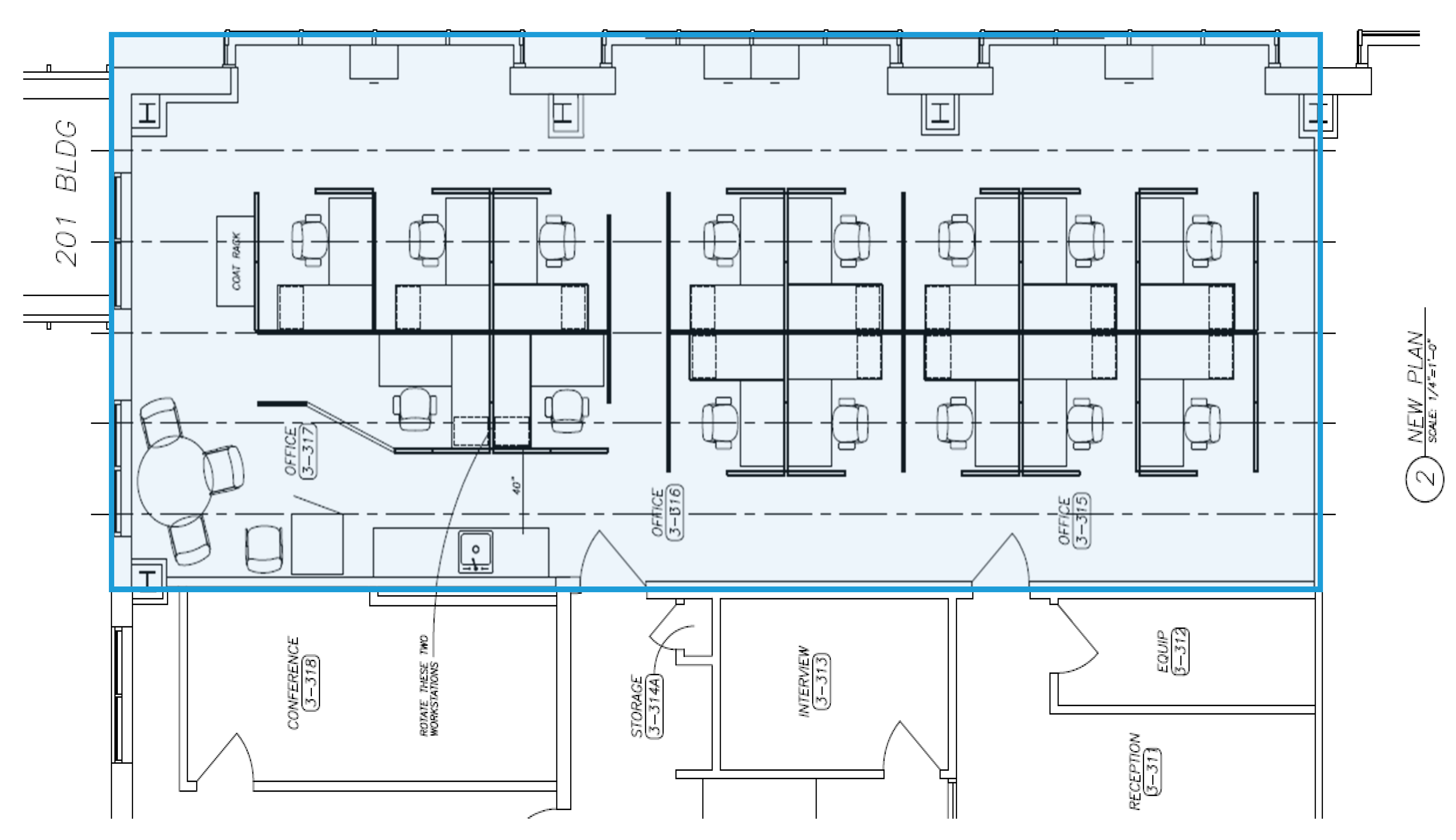

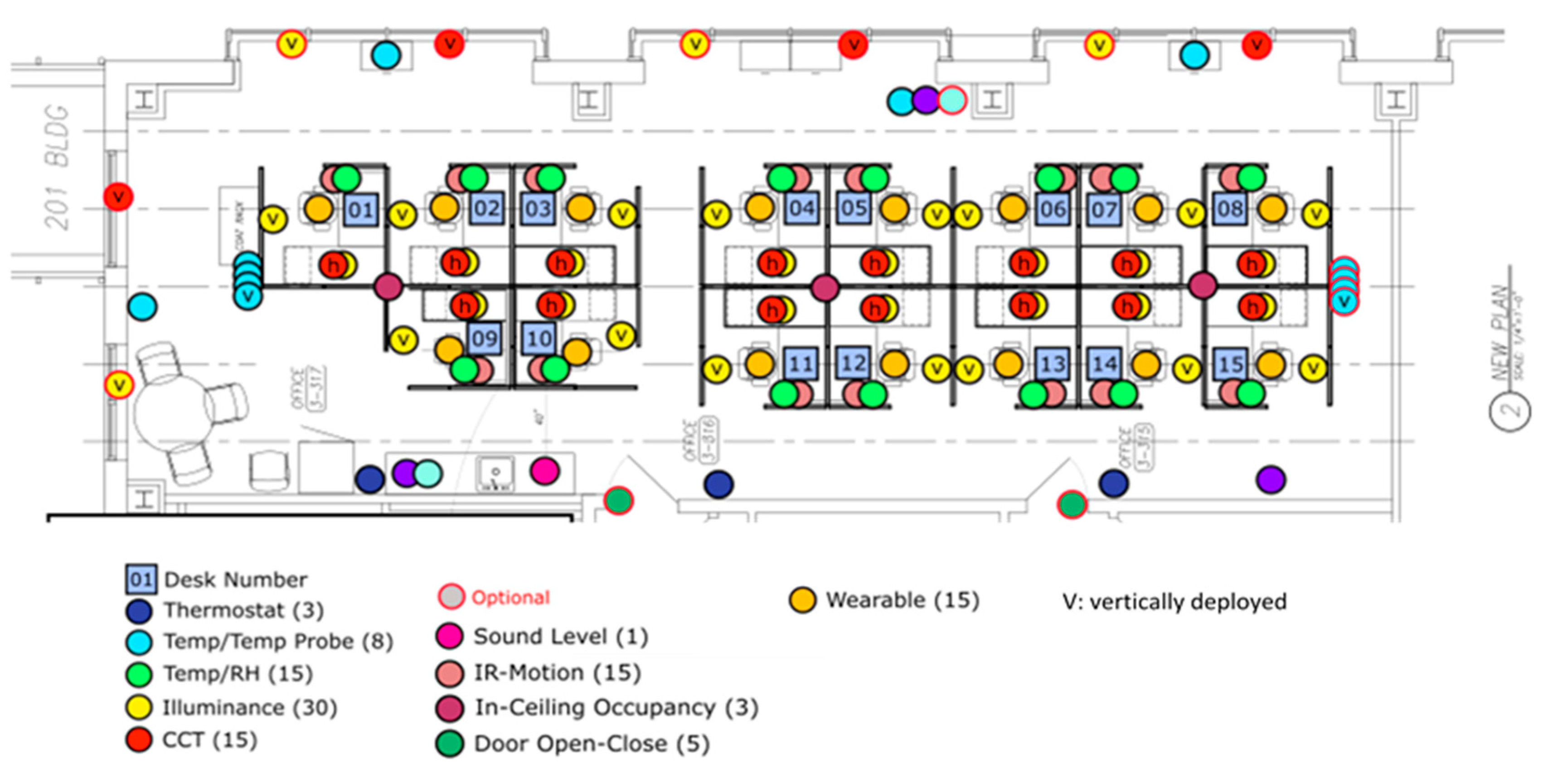

2.2. Office Configuration

2.3. Lighting System Design

2.4. Participants

2.4.1. Participant Exclusion Criteria

- -

- diagnosed sleep disorders,

- -

- severe vision problems,

- -

- sensitivity to light resulting in headaches or seizures,

- -

- cognitive abilities interfering with typical office work,

- -

- physical disabilities interfering with typical office work,

- -

- severe mood disorders, and

- -

- drug or alcohol dependency.

2.4.2. Demographic Information

2.4.3. Chronotype

2.5. Environmental Measurement Methods

- -

- Lighting environment: wireless real-time sensors (Lux1000 and Color Lux1000, Wovyn LLC, Heber City, UT, USA) were deployed at the horizontal desk surfaces and vertical window surfaces to measure the illuminance and CCT.

- -

- Thermal environment: wireless real-time sensors (Monnit Corp., South Salt Lake, UT, USA) were deployed at each desk to measure the thermal environmental parameters that may affect occupant performance and satisfaction, including temperature, relative humidity, and radiant temperature.

- -

- Acoustic environment: a real-time acoustic analyzer (XL2 audio and acoustic analyzer with M2211 microphone, NTi Audio Inc., Schaan, Liechtenstein) was deployed to measure the equivalent sound level for acoustic evaluations.

- -

- Indoor air quality: measure the module-level ventilation rates for indoor air quality evaluations.

- -

- Building operations: measure operational parameters of the building system, including the shades operation and electrochromic glass control.

2.6. Behavioral Outcome Measurement Methods

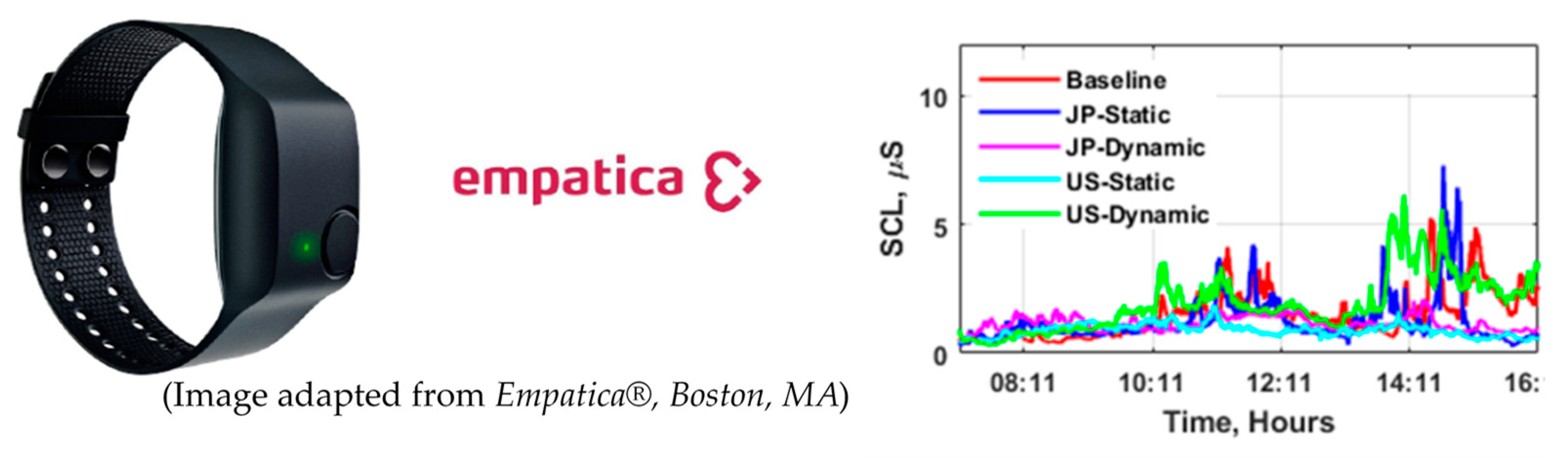

2.6.1. Stress

- Objective physiological measurements

- Daily subjective stress measurement

- Monthly subjective stress measurement

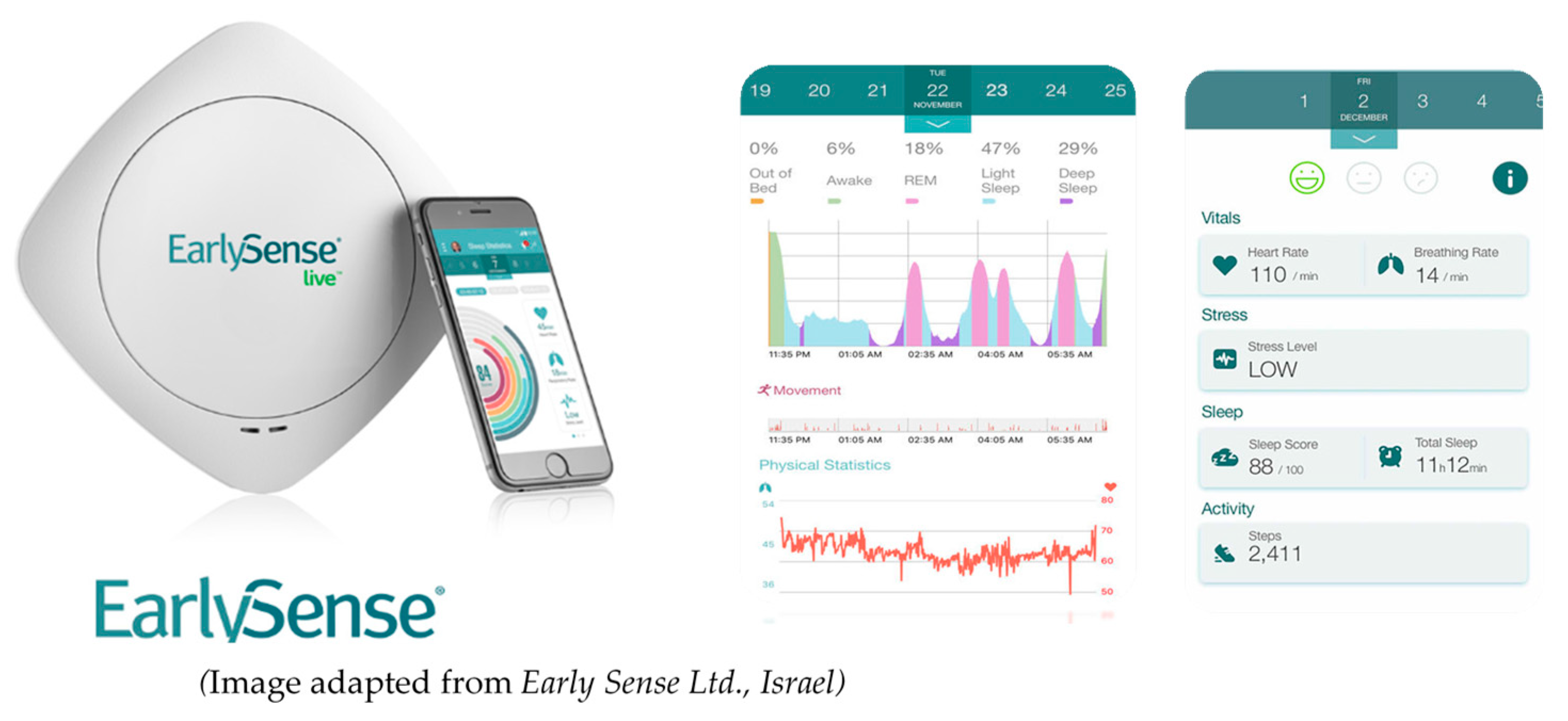

2.6.2. Sleep and Circadian Rhythms

- Objective real-time sleep tracking

- Daily subjective measurement—sleep diary

- Daily subjective measurement—alertness

- Monthly sleep quality measurement

2.6.3. Productivity

2.6.4. Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

- Satisfaction

- Visual comfort

- Mood

- Naturalness

2.7. Statistical Analysis Method

3. Lighting Configuration and Environmental Data Analysis Results

3.1. Evaluation of the Lighting Settings for This Study

3.2. Analysis of the Actual Lighting Environment during This Study

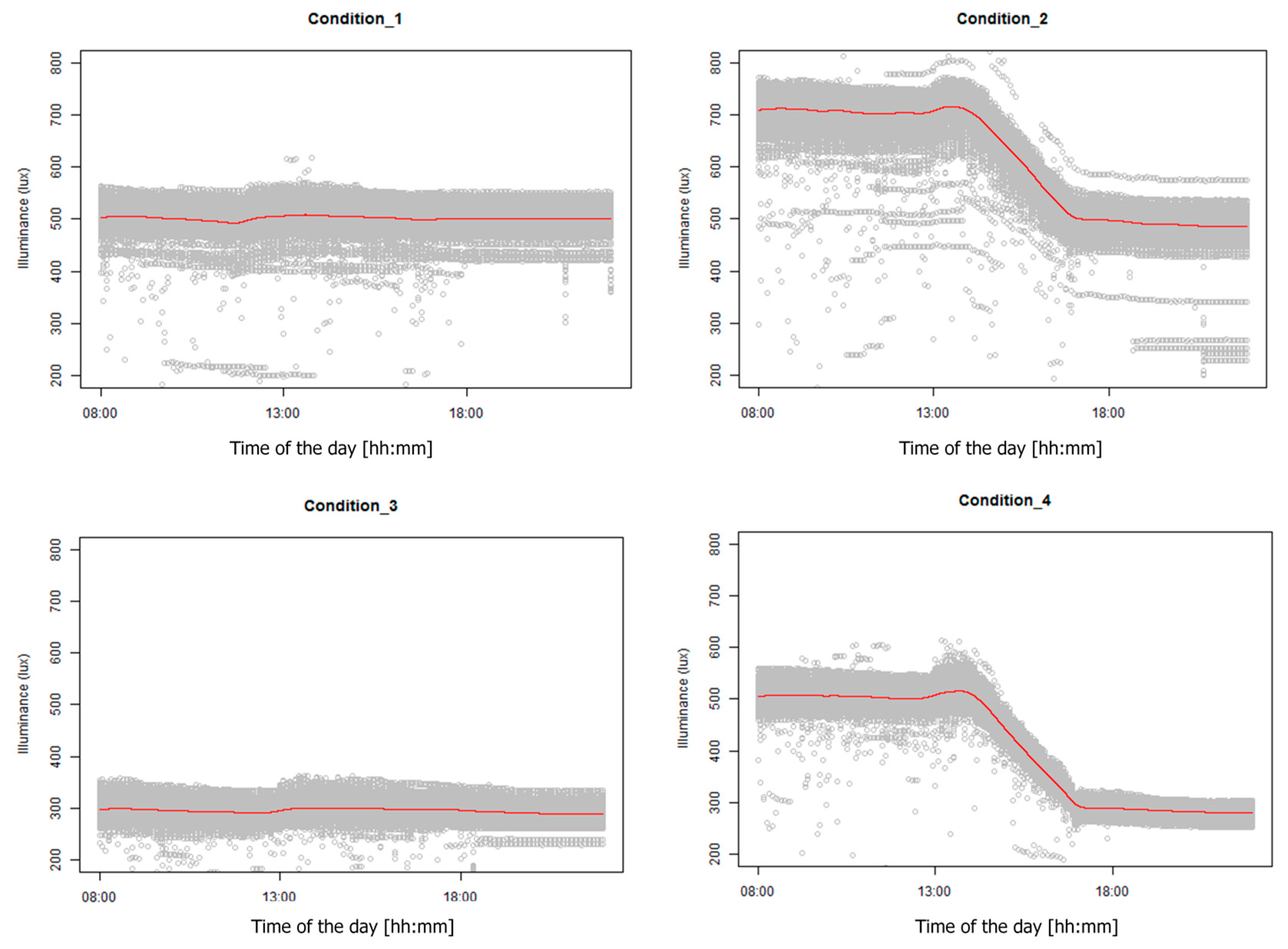

3.2.1. Temporal Illuminance Variations

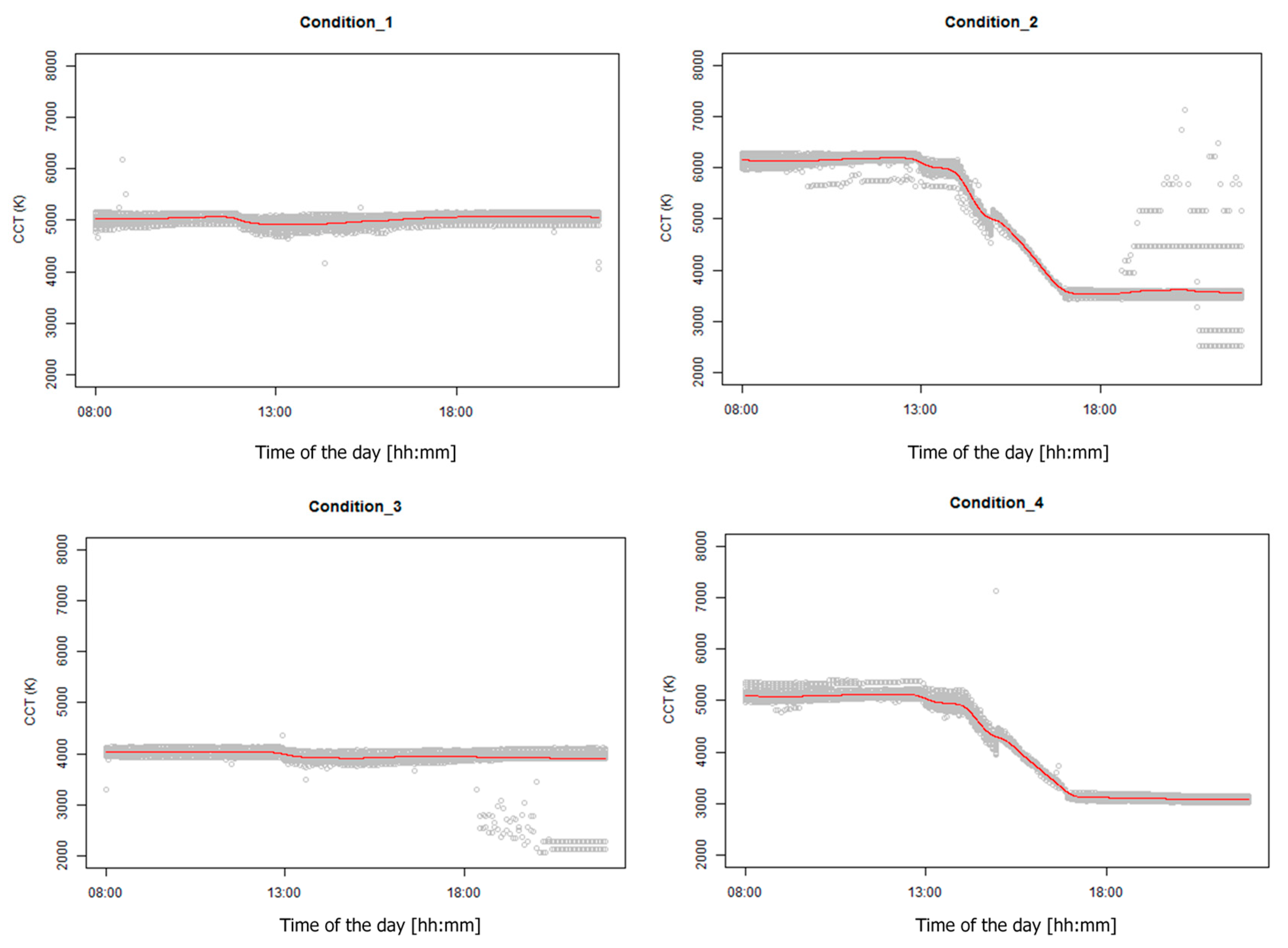

3.2.2. Temporal Lighting Correlated Color Temperature Variations

3.3. Theoretical Quantification of the Non-Visual Impact of the Dynamic Lighting

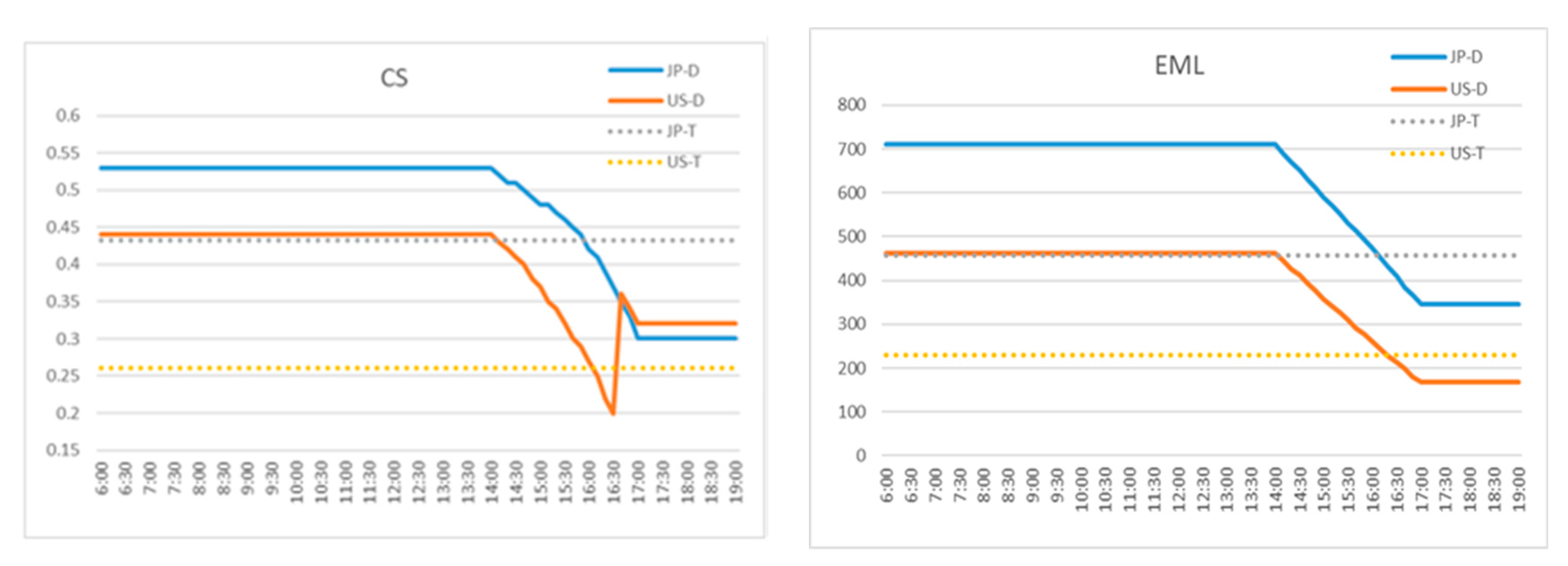

3.3.1. Lighting Property Data Analysis

3.3.2. Non-Visual Impact Estimation and Analysis

3.4. Evaluation of Indoor Non-Lighting Environment and System Operations

4. Behavioral Data Analysis Results

4.1. Mental Stress Analysis

4.1.1. Subjective Stress Analysis

4.1.2. Objective Stress Analysis

4.2. Sleep Analysis

4.2.1. Perceived Sleep Quality

- Daily sleep quality

- Monthly sleep quality

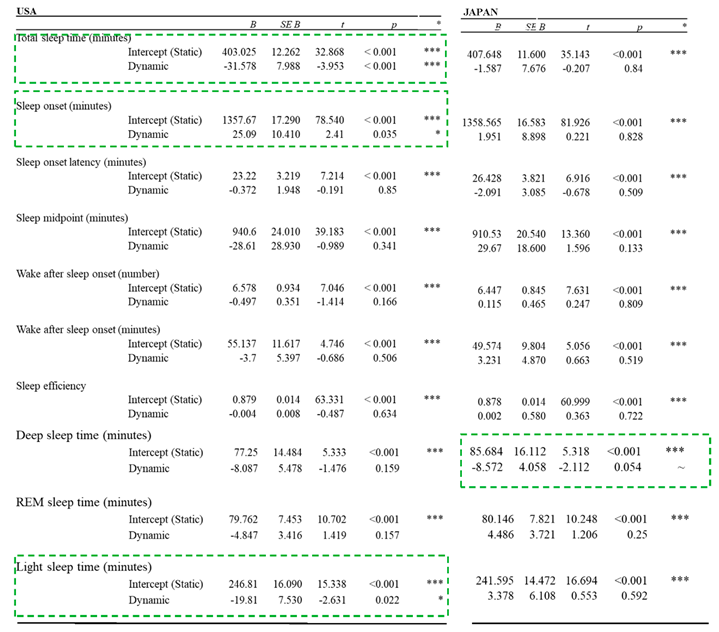

4.2.2. Nighttime Sleep Analysis

- Total sleep time

- Sleep onset

- Time in deep sleep

- Time in light sleep

- Other sleep parameters

4.2.3. Alertness—Perceived Feeling of Sleepiness during Daytime

4.3. Productivity Analysis

4.4. Secondary Measures Analysis

4.4.1. Satisfaction

- Satisfaction with lighting

- Satisfaction with other environmental parameters

4.4.2. Visual Comfort

4.4.3. Mood Analysis

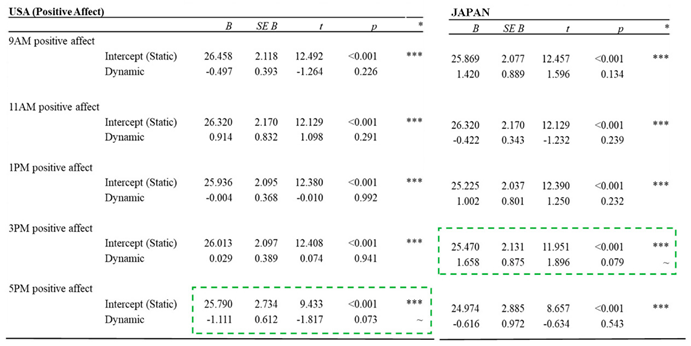

- Positive affect

- Negative affect

4.4.4. Perceived Naturalness of the Light

5. Discussions

5.1. Daytime Impacts

5.2. Nighttime Impacts

5.3. Recommendations for Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellia, L.; Bisegna, F.; Spada, G. Lighting in indoor environments: Visual and non-visual effects of light sources with different spectral power distributions. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International WELL Building Insititute (IWBI). The WELL Building Standard; IWBI: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, S.; Krueger, H. Effect of brightness distribution and light colours on office staff. Eur. Light. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, M.; Gordijn, M.C.M.; Beersma, D.G.M.; de Vries, B.; Daan, S. Time-of-day-dependent effects of bright light exposure on human psychophysiology: Comparison of daytime and nighttime exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 290, R1413–R1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lockley, S.W.; Evans, E.E.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Brainard, G.C.; Czeisler, C.A.; Aeschbach, D. Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 2006, 29, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veitch, J.A.; Fotios, S.A.; Houser, K.W. Judging the scientific quality of applied lighting judging the scientific quality of applied lighting research. J. Illum. Eng. Soc. 2019, 15, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hattar, S.; Liao, H.W.; Takao, M.; Berson, D.M.; Yau, K.W. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: Architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science 2002, 295, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hankins, M.W.; Peirson, S.N.; Foster, R.G. Melanopsin: An exciting photopigment. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berson, D.M.; Dunn, F.A.; Takao, M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science 2002, 295, 1070–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Duijnhoven, J.; Aarts, M.P.J.; Aries, M.B.C. Systematic review on the interaction between office light conditions and occupational health: Elucidating gaps and methodological issues. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czeisler, C.A.; Allan, J.S.; Strogatz, S.H.; Ronda, J.M.; Sánchez, R.; Ríos, C.D.; Freitag, W.O.; Richardson, G.S.; Kronauer, R.E. Bright light resets the human circadian pacemaker independent of the timing of the sleep-wake cycle. Science 1986, 233, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gooley, J.J.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Brainard, G.C.; Kronauer, R.E.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Spectral responses of the human circadian system depend on the irradiance and duration of exposure to light. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lucas, R.J. Mammalian inner retinal photoreception. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R125–R133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vandewalle, G.; Maquet, P.; Dijk, D.-J. Light as a modulator of cognitive brain function. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provencio, I.; Rodriguez, I.R.; Jiang, G.; Hayes, W.P.; Moreira, E.F.; Rollag, M.D. A novel human opsin in the inner retina. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dacey, D.M.; Liao, H.-W.; Peterson, B.B.; Robinson, F.R.; Smith, V.C.; Pokorny, J.; Yau, K.-W.; Gamlin, P.D. Melanopsin-expressing ganglion cells in primate retina signal colour and irradiance and project to the LGN. Nature 2005, 433, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainard, G.C.; Hanifin, J.P. Action spectrum for melatonin suppression: Evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor in the human eye. In Biologic Effects of Light 2001; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Thapan, K.; Arendt, J.; Skene, D.J. An action spectrum for melatonin suppression: Evidence for a novel non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor system in humans. J. Physiol. 2001, 535, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajochen, C.; Münch, M.; Kobialka, S.; Kräuchi, K.; Steiner, R.; Oelhafen, P.; Orgül, S.; Wirz-Justice, A. High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandewalle, G.; Gais, S.; Schabus, M.; Balteau, E.; Carrier, J.; Darsaud, A.; Sterpenich, V.; Albouy, G.; Dijk, D.J.; Maquet, P. Wavelength-dependent modulation of brain responses to a working memory task by daytime light exposure. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2788–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandewalle, G.; Schmidt, C.; Albouy, G.; Sterpenich, V.; Darsaud, A.; Rauchs, G.; Berken, P.-Y.; Balteau, E.; Degueldre, C.; Luxen, A.; et al. Brain responses to violet, blue, and green monochromatic light exposures in humans: Prominent role of blue light and the brainstem. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skene, D.J.; Lockley, S.W.; Thapan, K.; Arendt, J. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2019, 39, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittendrigh, C.S. Temporal organization: Reflections of a darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1993, 55, 17–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewy, A.J.; Wehr, T.A.; Goodwin, F.K.; Newsome, D.A.; Markey, S.P. Light suppresses melatonin secretion in humans. Science 1980, 210, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, K.E.; Jablonski, M.R.; Warfield, B.; Cecil, K.S.; James, M.; Ayers, M.A.; Maida, J.; Bowen, C.; Sliney, D.H.; Rollag, M.D.; et al. Blue light from light-emitting diodes elicits a dose-dependent suppression of melatonin in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 110, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Korkmaz, A.; Erren, T.C.; Piekarski, C.; Tamura, H.; Manchester, L.C. Light at night, chronodisruption, melatonin suppression, and cancer risk: A review. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2007, 13, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooley, J.J.; Chamberlain, K.; Smith, K.A.; Khalsa, B.S.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; van Reen, E.; Zeitzer, J.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses melatonin onset and shortens melatonin duration in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mills, P.R.; Tomkins, S.C.; Schlangen, L.J.M. The effect of high correlated colour temperature office lighting on employee wellbeing and work performance. J. Circadian Rhythms 2007, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phipps-Nelson, J.; Redman, J.R.; Dijk, D.-J.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W. Daytime exposure to bright light, as compared to dim light, decreases sleepiness and improves psychomotor vigilance performance. Sleep 2003, 26, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.U.; James, L.M.; Schlangen, L.J.M.; Dijk, D.-J. Blue-enriched white light in the workplace improves self-reported alertness, performance and sleep quality. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2008, 34, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mukae, H.; Sato, M. The effect of color temperature of lighting sources on the autonomic nervous functions. Ann. Physiol. Anthropol. 1992, 11, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deguchi, T.; Sato, M. The effect of color temperature of lighting sources on mental activity level. Ann. Physiol. Anthropol. 1992, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lucas, R.J.; Peirson, S.N.; Berson, D.M.; Brown, T.M.; Cooper, H.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gamlin, P.D.; Lockley, S.W.; O’Hagan, J.B.; et al. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souman, J.L.; Tinga, A.M.; Pas, T.S.F.; van Ee, R.; Vlaskamp, B.N.S. Acute alerting effects of light: A systematic literature review. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 337, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Dinges, D.F. Sleep deprivation and vigilant attention. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1129, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, M.W.; Chuah, L.Y. Functional neuroimaging insights into how sleep and sleep deprivation affect memory and cognition. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008, 24, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S.; Dinges, D.F. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007, 3, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leder, S.; Newsham, G.R.; Veitch, J.A.; Mancini, S.; Charles, K.E. Effects of office environment on employee satisfaction: A new analysis. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, J.H.; Loftness, V.; Aziz, A. Post-occupancy evaluation of 20 office buildings as basis for future IEQ standards and guidelines. Energy Build. 2012, 46, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.A.; Charles, K.E.; Farley, K.M.J.; Newsham, G.R. A model of satisfaction with open-plan office conditions: COPE field findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De, Y.; Phd, K.; Smolders, K. Effects of dynamic lighting on office workers: First results of a field study with monthly alternating settings. Lighting Res. Technol. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larzelere, M.M.; Jones, G.N. Stress and health. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2008, 35, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellman, J.M.; International Labour Office. Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety; International Labor Office: Genève, Switzerland, 1998; ISBN 9221092038. [Google Scholar]

- Smoot, S.L.; Gonzales, J.L. Cost-effective communication skills training for state hospital employees. Psychiatr. Serv. 1995, 46, 819–822. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Mccoy, J.M. When buildings don’t work: The role of architecture in human health. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liebl, A.; Haller, J.; Jödicke, B.; Baumgartner, H.; Schlittmeier, S.; Hellbrück, J. Combined effects of acoustic and visual distraction on cognitive performance and well-being. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.T.L.; Chen, H.; Tan, S.-C.; Hui, S.Y.R. Precise dimming and color control of LED Systems based on color mixing. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.-T.; Tan, S.-C.; Hui, S.Y.R. Nonlinear dimming and correlated color temperature control of bicolor white LED systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 6934–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mott, M.S.; Robinson, D.H.; Walden, A.; Burnette, J.; Rutherford, A.S. Illuminating the Effects of Dynamic Lighting on Student Learning. SAGE Open 2012, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haans, A. The natural preference in people’s appraisal of light. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nute, K.; Weiss, A.; Kaur-Bala, J.; Marrocco, R. The animation of the weather as a means of sustaining building occupants and the natural environment. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 8, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Smolders, K.C.H.J.; de Kort, Y.A.W. Investigating daytime effects of correlated colour temperature on experiences, performance, and arousal. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 50, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Jamrozik, A.; Campanella, C.; Aristizabal, S.; Zhang, R.; Clements, N. Living labs: Measuring human experience in the built environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aristizabal, S.; Porter, P.; Clements, N.; Campanella, C.; Zhang, R.; Hovde, K.; Lam, C. Conducting human-centered building science at the well living lab. Technol. Archit. Des. 2019, 3, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozik, A.; Clements, N.; Hasan, S.S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; Campanella, C.; Loftness, V.; Porter, P.; Ly, S.; Wang, S.; et al. Access to daylight and view in an office improves cognitive performance and satisfaction and reduces eyestrain: A controlled crossover study. Build. Environ. 2019, 165, 106379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, C.; Michel, U.; Randler, C. Outdoor Light at Night (LAN) is correlated with eveningness in adolescents. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.S.; Hébert, M.; Ledoux, É.; Gaudreault, M.; Laberge, L. Relationship of chronotype to sleep, light exposure, and work-related fatigue in student workers. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantermann, T.; Forstner, S.; Halle, M.; Schlangen, L.; Roenneberg, T.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A. The stimulating effect of bright light on physical performance depends on internal time. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horne, J.A.; Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 4, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Taillard, J.; Philip, P.; Chastang, J.-F.; Bioulac, B. Validation of horne and ostberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire in a middle-aged population of french workers. J. Biol. Rhythms 2004, 19, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, N.; Zhang, R.; Jamrozik, A.; Campanella, C.; Bauer, B. The spatial and temporal variability of the indoor environmental quality during three simulated office studies at a living lab. Buildings 2019, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Buijs, R.M. Light affects morning salivary cortisol in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 3395–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, J.A.; Picard, R.W. Detecting stress during real-world driving tasks using physiological sensors. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, J.; Gutierrez-Osuna, R. Using heart rate monitors to detect mental stress. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks, Berkeley, CA, USA, 3–5 June 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakoshi, T.; Yamakoshi, K.; Tanaka, S.; Nogawa, M.; Park, S.B.; Shibata, M.; Sawada, Y.; Rolfe, P.; Hirose, Y. Feasibility study on driver’s stress detection from differential skin temperature measurement. In Proceedings of the 2008 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–25 August 2008; pp. 1076–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, M.; Lai, M.; Bender, D.; Picard, R.W.; Tognetti, S. Empatica E3—A wearable wireless multi-sensor device for real-time computerized biofeedback and data acquisition. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Wireless Mobile Communication and Healthcare—Transforming Healthcare Through Innovations in Mobile and Wireless Technologies (MOBIHEALTH), Athens, Greece, 3–5 November 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lykken, D.T.; Venables, P.H. Direct measurement of skin conductance: A proposal for standardization. Psychophysiology 1971, 8, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gersak, G.; Drnovsek, J. Electrodermal activity patient simulator. PLoS ONE 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucsein, W. Electrodermal Activity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4614-1126-0. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, M.; Kaernbach, C. A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. J. Neurosci. Methods 2010, 190, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boucsein, W.; Fowles, D.C.; Grimnes, S.; Ben-Shakhar, G.; Roth, W.T.; Dawson, M.E.; Filion, D.L. Society for psychophysiological research Ad Hoc committee on electrodermal measures publication recommendations for electrodermal measurements. Psychophysiology 2012, 49, 1017–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoud, M.; Chaaya, H.; Osman, G.; Naassan, Z. Validation of the Arabic version of the Cohen perceived stress scale (PSS-10) among pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, T.; De Cieri, H. Workplace Stress Evaluation Tools: A Snapshot Review. 2011. Available online: https://research.iscrr.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/297758/Workplace-stress-evaluation-tools-snapshot.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Tal, A.; Shinar, Z.; Shaki, D.; Codish, S.; Goldbart, A. Validation of contact-free sleep monitoring device with comparison to polysomnography. J. Clin. Sleep Med. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoddes, E.; Zarcone, V.; Smythe, H.; Phillips, R.; Dement, W.C. Quantification of sleepiness: A new approach. Psychophysiology 1973, 10, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Hoch, C.C.; Yeager, A.L.; Kupfer, D.J. Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 1991, 14, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. Are Humans Good Sensors? Using Occupants as Sensors for Indoor Environmental Quality Assessment and for Developing Thresholds that Matter. Carnegie Mellon University. 2015. Available online: https://kilthub.cmu.edu/ndownloader/files/12247823 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M.; Walker, S.C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RC Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, J. Effect displays in R for generalised linear models. J. Stat. Softw. 2003, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore-Ede, M. Taking the obesity and diabetes risk out of light at night. In Proceedings of the Lighting for Health and Wellbeing, Newport Beach, CA, USA, 30 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiro, M.; Rea, M. Quantifying circadian light and its impact. J. Am. Inst. Arch. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bailes, H.J.; Lucas, R.J. Human melanopsin forms a pigment maximally sensitive to blue light supporting activation of G(q/11) and G(i/o) signalling cascades. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore-ede, M.; Heitmann, A.; Guttkuhn, R. Circadian potency spectrum with extended exposure to polychromatic white LED Light under workplace conditions. J. Biol. Rhythms 2020, 35, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, M.; Figueiro, M.; Bullough, J.; Bierman, A. A model of phototransduction by the human circadian system. Brain Res. Rev. 2005, 50, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.J. Irradiance Toolbox User Guide; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, S.; Samantha, A.; Zhao, J.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, R. Circadian lighting and its smart control strategy: A review. Illum. Eng. J. 2017, 28, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- ASHRAE. Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jamrozik, A.; Ramos, C.; Zhao, J.; Bernau, J.; Clements, N.; Wolf, T.V.; Bauer, B. A novel methodology to realistically monitor office occupant reactions and environmental conditions using a living lab. Build. Environ. 2018, 130, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pail, G.; Huf, W.; Pjrek, E.; Winkler, D.; Willeit, M.; Praschak-Rieder, N.; Kasper, S. Bright-light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders. Neuropsychobiology 2011, 64, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partonen, T.; Lonnqvist, J. Bright Light Improves Vitality and Alleviates Distress in Healthy People. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 57, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küller, R.; Ballal, S.; Laike, T.; Mikellides, B.; Tonello, G. The impact of light and colour on psychological mood: A cross-cultural study of indoor work environments. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voogt, E.; van der Heide, A.; van Leeuwen, A.F.; Visser, A.P.; Cleiren, M.P.H.D.; Passchier, J.; van der Maas, P.J. Positive and negative affect after diagnosis of advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Race | Number |

| White | 12 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Income | Number |

| Less than $10,000 | 1 |

| $35,000 to less than $50,000 | 1 |

| $50,000 to less than $75,000 | 4 |

| $75,000 or more | 7 |

| Preferred not to answer | 2 |

| Education | Number |

| Some college or technical school | 4 |

| College graduate | 11 |

| Chronotype (Morning–Eveningness Questionnaire) | Number |

| Definite morning | 1 |

| Moderate morning | 5 |

| Intermediate | 8 |

| Moderate evening | 1 |

| Definite evening | 0 |

| Baseline Sleep and Stress Measures | Average (SD) |

| Sleep Quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) | 5.33 (2.69) |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 25.73 (6.94) |

| Job Stress Scale | 12.13 (3.78) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Campanella, C.; Aristizabal, S.; Jamrozik, A.; Zhao, J.; Porter, P.; Ly, S.; Bauer, B.A. Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197217

Zhang R, Campanella C, Aristizabal S, Jamrozik A, Zhao J, Porter P, Ly S, Bauer BA. Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197217

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Rongpeng, Carolina Campanella, Sara Aristizabal, Anja Jamrozik, Jie Zhao, Paige Porter, Shaun Ly, and Brent A. Bauer. 2020. "Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197217

APA StyleZhang, R., Campanella, C., Aristizabal, S., Jamrozik, A., Zhao, J., Porter, P., Ly, S., & Bauer, B. A. (2020). Impacts of Dynamic LED Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7217. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197217