How to Improve Patient Safety Literacy?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. What Is Health Literacy?

1.2. Impact of Health Literacy on Patient Safety

1.3. How to Improve Health Literacy for Patient Safety?

2. Materials and Methods

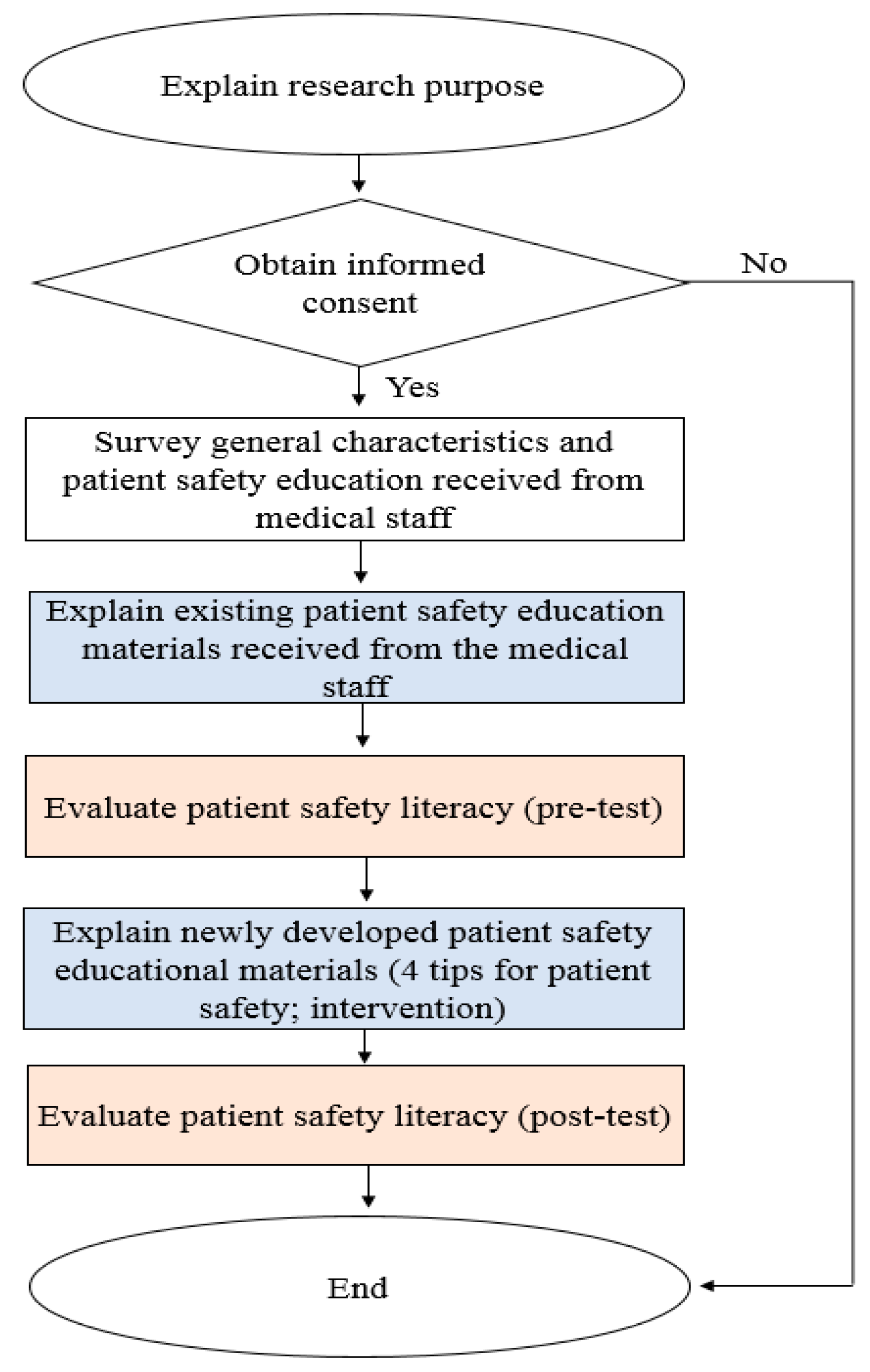

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

2.3. Development of Patient Safety Educational Materials

2.3.1. Patients/Families

- “I have received a lot of education from doctors and nurses in hospitals. However, after the training I can’t remember more than 80 % of the education provided by the medical staff.”

- “I don’t know what the doctor or nurse is saying or what patient safety is.”

- “When I go to the hospital, the doctor or nurse tells me what they want to say and don’t listen to me.”

- “I write down the questions in advance and ask the doctor. My body must be taken care of by me.”

- “I know my health condition and it’s important for me to tell the doctor about it. However, the doctor only talks and does not listen to me.”

2.3.2. Patient Safety Officers

- “The age of unilateral education for patients seems to be over. The materials of patient safety education in Korea are too negative. Only irrelevant information is available in it. Such education does not guarantee patient safety.”

- “It seems important to advise patients to ask questions from doctors and nurses.”

- “Since there is so much education that patients need to receive, it is important to selectively conduct the necessary education at the same level every day.”

- “There should be a provision that allows patients to ask questions freely when they feel anxious.”

- “At the national level, campaigns should be created to develop a culture that can change the perceptions of patients, families, and staff in hospitals.”

- Things to prepare for admission;

- Time for doctors’ rounds and nurse patrol time;

- Patient identification method (S), fall prevention method (S), pain management, and hand hygiene (S);

- Guidance on preparation for hospitalization of pediatric patients;

- Informing about medicines before admission (S);

- Inpatient medical guardian appointment service, discharge procedure, application for copies of medical records, patients’ rights and obligations, voice of customer, social work, privacy protection request, and medical expense inquiry;

- Hospital room etiquette, mealtime, visit time, hospital facilities (including facilities for people with disabilities), fire prevention and evacuation tips (S), no smoking (S), prevention of theft, religious office, and parking fee.

2.4. Development of Patient Safety Literacy Tool

- Key question: What tools are available to assess health literacy (or patient safety literacy)?

- Search engines: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Database, KoreaMed, Korean Studies Information Service System, Korean Medical Database.

- Research methods: Full-text accessible paper (original study, evidence-based guideline, systematic review).

- Period: Unlimited (from the first publication on health literacy until 12 July 12 2019).

- Languages: English or Korean.

- Study subjects: Over 18 years old.

- Exclusion criteria: Studies focusing on health care providers (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, therapists, etc.) and teachers (teachers, professors, etc.).

- A total of 4447 documents were searched, and a total of seven health literacy tools were extracted, excluding duplicate or wrong topics.

- Were the patient safety educational materials (words, sentences, meanings, etc.) easy for you (the patients and their families) to understand? (“Easy to understand”).

- Did the patient safety educational materials help ensure safe hospitalization? (“Help in safe hospitalization”).

- Can you practice patient safety yourself without the help of others? (“Do it yourself”).

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Homogeneity Test

3.2. Comparisons between Pre- and Post-Patient Safety Literacy Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. Healthy People 2030. 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/our-work/healthy-people-2030/about-healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutilli, C.C. Do your patients understand? Determining your patients’ health literacy skills. Orthop. Nurs. 2005, 24, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarkar, U.; Schillinger, D.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Napoles, A.; Karliner, L.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Patient-physicians’ information exchange in outpatient cardiac care: Time for a heart to heart? Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanders, L.M.; Federico, S.; Klass, P.; Abrams, M.A.; Dreyer, B. Literacy and child health: A systematic review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sudore, R.L.; Yaffe, K.; Satterfield, S.; Harris, T.B.; Mehta, K.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Newman, A.B.; Rosano, C.; Rooks, R.; Rubin, S.M.; et al. Limited literacy and mortality in the elderly: The health, aging, and body composition study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, D.W.; Wolf, M.S.; Feinglass, J.; Thompson, J.A.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Huang, J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aspden, P.; Wolcott, J.; Bootman, J.L.; Cronenwett, L.R. Preventing Medication Errors: Quality Chasm Series; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.C.; Wolf, M.S.; Bass, P.F.; Middlebrooks, M.; Kennen, E.; Baker, D.W.; Bennett, C.L.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Bocchini, A.; Savory, S.; et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutner, M.; Greenberg, E.; Jin, Y.; Paulsen, C. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy; Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006483 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Rogers, W.J.; Canto, J.G.; Lambrew, C.T.; Tiefenbrunn, A.J.; Kinkaid, B.; Shoultz, D.A.; Frederick, P.D.; Every, N. Temporal trends in the treatment of over 1.5 million patients with myocardial infarction in the US from 1990 through 1999: The National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 1, 2 and 3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 2056–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lied, T.R.; Gonzalez, J.; Taparanskas, W.; Shukla, T. Trends and current drug utilization patterns of Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2006, 27, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nodhturft, V.; Schneider, J.M.; Hebert, P.; Bradham, D.D.; Bryant, M.; Phillips, M.; Russo, K.; Goettelman, D.; Aldahondo, A.; Clark, V.; et al. Chronic disease self-management: Improving health outcomes. Nurs. Clin. North. Am. 2000, 35, 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, J.I.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, H.A.; Kim, H.S.; Chun, J.H.; Kwak, M.J. Experiences in patient safety education of patient safety officer using focus group interview. Qual. Improv. Health Care 2019, 25, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seo, J.H.; Song, E.S.; Choi, S.E.; Woo, K.S. Patient Safety in Korea: Current Status and Policy Issues; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.S.; Bailey, S.C. The Role of Health Literacy in Patient Safety. Perspectives on Safety. San Francisco. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2009. Available online: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspective/role-health-literacy-patient-safety (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. A 5 year Comprehensive Plan for Patient Safety (2018~2022). Ministry of Health and Welfare, Sejog, South Korea. 2018. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=0319&CONT_SEQ=344873&page=1 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Kim, Y.S.; Kwak, M.J.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.A.; Kim, H.S.; Chun, J.H.; Hwang, J.I. Safety education programs for patients and families in overseas institutions. Qual. Improv. Health Care 2019, 2, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.H.; Eun, Y. Health literacy of inpatients at general hospital. Korean J. Adult Nurs. 2012, 24, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, E.J. The influence of functional literacy on perceived health status in Korean older adults. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2008, 38, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y. Influencing factors on functional health literacy among the rural elderly. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2011, 22, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, D.W.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Sudano, J.; Patterson, M. The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2000, 55, S368–S374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.A.; Chun, J.; Kwak, M.J.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, J.I.; Kim, J. Can patient and family education prevent medical errors? A descriptive study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.L.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Williams, M.V.; Baker, D.W. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med. Care 2002, 40, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, M.L.; Pandit, A.U.; Bergeron, A.R.; Cameron, K.A.; Ross, E.; Wolf, M.S. Ask, understand, remember: A brief measure of patient communication self-efficacy within clinical encounters. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 (Suppl. 2), 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, M.G.; Jacobson, T.A.; Veledar, E.; Kripalani, S. Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: A mixed-methods analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sim, K.H. Tips for creating effective health education materials. J. Korean Diabetes. 2011, 12, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joint Commission. “What Did the Doctor Say?” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety; The Joint Commission: Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, L.A. Health Literacy and Patient Safety Events. Pa. Patient Saf. Auth. 2016, 13, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

| Tool | Number of Items | Time 1 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | Applicability (Total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine | 66 | 3–6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine - Revised | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 27 |

| Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults | Reading comprehension 50 Numerical ability 17 | 22–25 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults | Reading comprehension 36 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 16 |

| Screening Questions for Limited Health Literacy | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 32 |

| Single Item Literacy Screen | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 22 |

| Variable | Patient, n = 123 | Family, n = 94 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 63 | 51.2 | 66 | 70.2 | 0.005 ** |

| Male | 60 | 48.8 | 28 | 29.8 | |

| Age range (years) | |||||

| ≤ 30 | 15 | 12.2 | 12 | 12.8 | 0.092 |

| 31–40 | 22 | 17.9 | 25 | 26.6 | |

| 41–50 | 23 | 18.7 | 24 | 25.5 | |

| 51–60 | 23 | 18.7 | 17 | 18.1 | |

| ≥ 61 | 40 | 32.5 | 16 | 17.0 | |

| Education level | |||||

| Elementary school or below | 9 | 7.3 | 6 | 6.4 | 0.164 |

| Middle school | 12 | 9.8 | 8 | 8.5 | |

| High school | 45 | 36.6 | 21 | 22.3 | |

| College | 45 | 36.6 | 48 | 51.1 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 12 | 9.8 | 11 | 11.7 | |

| Patient safety education received from medical staff | |||||

| Handwashing methods (y) | 68 | 55.3 | 46 | 48.9 | 0.353 |

| Preventing falls (y) | 96 | 57.5 | 71 | 42.5 | 0.663 |

| Orientation to hospitalization (y) | 84 | 68.3 | 63 | 67.0 | 0.843 |

| Tell your medicines (y) | 86 | 69.9 | 61 | 64.9 | 0.433 |

| Tell your health condition (y) | 83 | 67.5 | 58 | 61.7 | 0.377 |

| How to participate in health-related decision-making (y) | 59 | 48.0 | 36 | 38.3 | 0.155 |

| Prepare a list to ask your doctor (y) | 24 | 19.5 | 15 | 16.0 | 0.499 |

| Variable | Total, n = 217 | p Value | Patient, n = 123 | p Value | Family, n = 94 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Easy to understand | ||||||

| Pre | 3.05 (0.55) | 0.006 ** | 3.02 (0.57) | 0.017 * | 3.09 (0.52) | 0.151 |

| Post | 3.17 (0.64) | 3.15 (0.68) | 3.18 (0.59) | |||

| Help in safe hospitalization | ||||||

| Pre | 2.85 (0.63) | 0.000 *** | 2.84 (0.63) | 0.000 *** | 2.86 (0.63) | 0.000 *** |

| Post | 3.20 (0.47) | 3.17 (0.49) | 3.24 (0.85) | |||

| Do it yourself | ||||||

| Pre | 3.35 (0.80) | 0.004 ** | 3.37 (0.76) | 0.038 * | 3.32 (0.85) | 0.050 |

| Post | 3.49 (0.76) | 3.50 (0.80) | 3.48 (0.71) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, H.A.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Kwak, M.J.; Chun, J.; Hwang, J.-I.; Kim, H. How to Improve Patient Safety Literacy? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197308

Kim Y-S, Kim HA, Kim M-S, Kim HS, Kwak MJ, Chun J, Hwang J-I, Kim H. How to Improve Patient Safety Literacy? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(19):7308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197308

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yoon-Sook, Hyun Ah Kim, Moon-Sook Kim, Hyuo Sun Kim, Mi Jeong Kwak, Jahae Chun, Jee-In Hwang, and Hyeran Kim. 2020. "How to Improve Patient Safety Literacy?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 19: 7308. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197308