Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Aboriginal Respondents

3.2. Respondents in Financial Hardship

3.3. General Community Respondents

4. Discussion

4.1. Aboriginal Respondents

4.2. Respondents Living with Financial Disadvantage

4.3. Other Members of the General Community

4.4. Belonging and Inclusivity Make for a Resilient Future

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Brief Weather-Related Disaster Trauma Exposure and Impact Screen

Development and Source

| Item | Derivation |

| A weather disaster (e.g., flood, bushfire, storm, cyclone) damage or destroy your home. | Adapted from ‘trauma exposure’ items in McDermott et al. [19,77]: ‘experienced damage to [your] home, including broken windows, damage to part or all of [your] roof or other home damage’. Exposure to the traumatic event (i.e., witnessing actual flames) and proxy measures of exposure such as home damage, are significant predictors of adverse emotional outcomes in all published predictive models. |

| Did any of the following happen as a result of this weather-related disaster?(a) You thought you might die | Adapted from O’Donnell [76], item #6 from the final ten-item measure, p.929, ‘During the event, I thought I was about to die’; and adapted from McDermott et al. [19,77]. In the latter research, of all measured variables, threat perception had the strongest relationship with post-disaster post-traumatic stress disorder. |

| (b) You personally knew people who were killed or badly injured. | Adapted from O’Donnell [76], item #6 from the original list of peri-trauma items, p.926, ‘I witnessed other people being killed or injured’; and adapted from McDermott et al. [19,77], perceived threat of death to self and perceived threat of death to parents (for children and adolescents). |

| (c) You felt terrified, helpless or hopeless. | Consistent with diagnostic criteria (A2) for PTSD (DSMIV) and ICD entry criteria. Adapted from O’Donnell [76], item #5 from the final ten-item measure, p.929, ‘At the time of the event, I felt terrified, helpless or hopeless’. |

| (d) You are still currently distressed about it. | Allows calculation of point prevalence of post-disaster distress and differentiation from other possible causes of anxiety; can be validated against related constructs measured in the same survey. This item provides insight into whether ongoing stress and anxiety are directly related to the traumatic event (in addition to any relationships we may find with other measures of health and wellbeing). |

Appendix B

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Social Capital Constructs within the Northern Rivers Community Recovery after Flood Survey (n = 2046)

| Construct | Stata | Amos # | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal Social Connection | x1: I make time to keep in touch with my friends | 0.83 | *** | 0.79 | |

| x2: I chat with my neighbours when I see them | 0.60 | *** | 0.62 | *** | |

| x3: I spend time with extended family members (relatives who don’t live with me) | 0.60 | *** | 0.49 | *** | |

| RMSEA (95% CIs) | 0.000(0.000–0.040) | 0.071(0.030–0.119) | |||

| CFI | 1.000 | 0.963 | |||

| Civic Engagement | x1: I take part in community-based clubs or associations (e.g., Rotary, CWA, book club, Lions) | 0.81 | *** | 0.63 | |

| x2: I go to arts or cultural events | 0.45 | *** | 0.34 | *** | |

| x3: I attend community events such as farmers’ markets, festivals and shows | 0.45 | *** | 0.38 | *** | |

| x4: I take part in sports activities or groups | 0.60 | *** | 0.53 | *** | |

| x5: I volunteer locally (e.g., Meals on Wheels, school fete, Rural Fire Service) | 0.79 | *** | 0.66 | *** | |

| RMSEA (95% CIs) | 0.058(0.041–0.078) | 0.044(0.018–0.073) | |||

| CFI | 0.991 | 0.989 | |||

| Sense of Belonging | x1: When I feel lonely there are several people I could call and talk to | 0.83 | *** | 0.78 | |

| x2: I have family or friends I can confide in | 0.86 | *** | 0.79 | *** | |

| x3: I feel that I’m on the fringe in my circle of friends (reverse scored) | 0.43 | *** | 0.34 | *** | |

| x4: I don’t often get invited to do things with others (reverse scored) | 0.45 | *** | 0.35 | *** | |

| x5: There are people outside my household who can offer help in a crisis | 0.73 | *** | 0.67 | *** | |

| RMSEA (95% CIs) | 0.048(0.028–0.071) | 0.025(0.000–0.055) | |||

| CFI | 0.997 | 0.999 | |||

| Feelings of Belonging | x1: I feel like an outsider (reversed scored) | 0.67 | *** | 0.67 | |

| x2: I feel that I belong | 0.88 | *** | 0.85 | *** | |

| x3: I feel included | 0.88 | *** | 0.85 | *** | |

| RMSEA | 0.000(0.000–0.050) | 0.000(0.000–0.067) | |||

| CFI | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

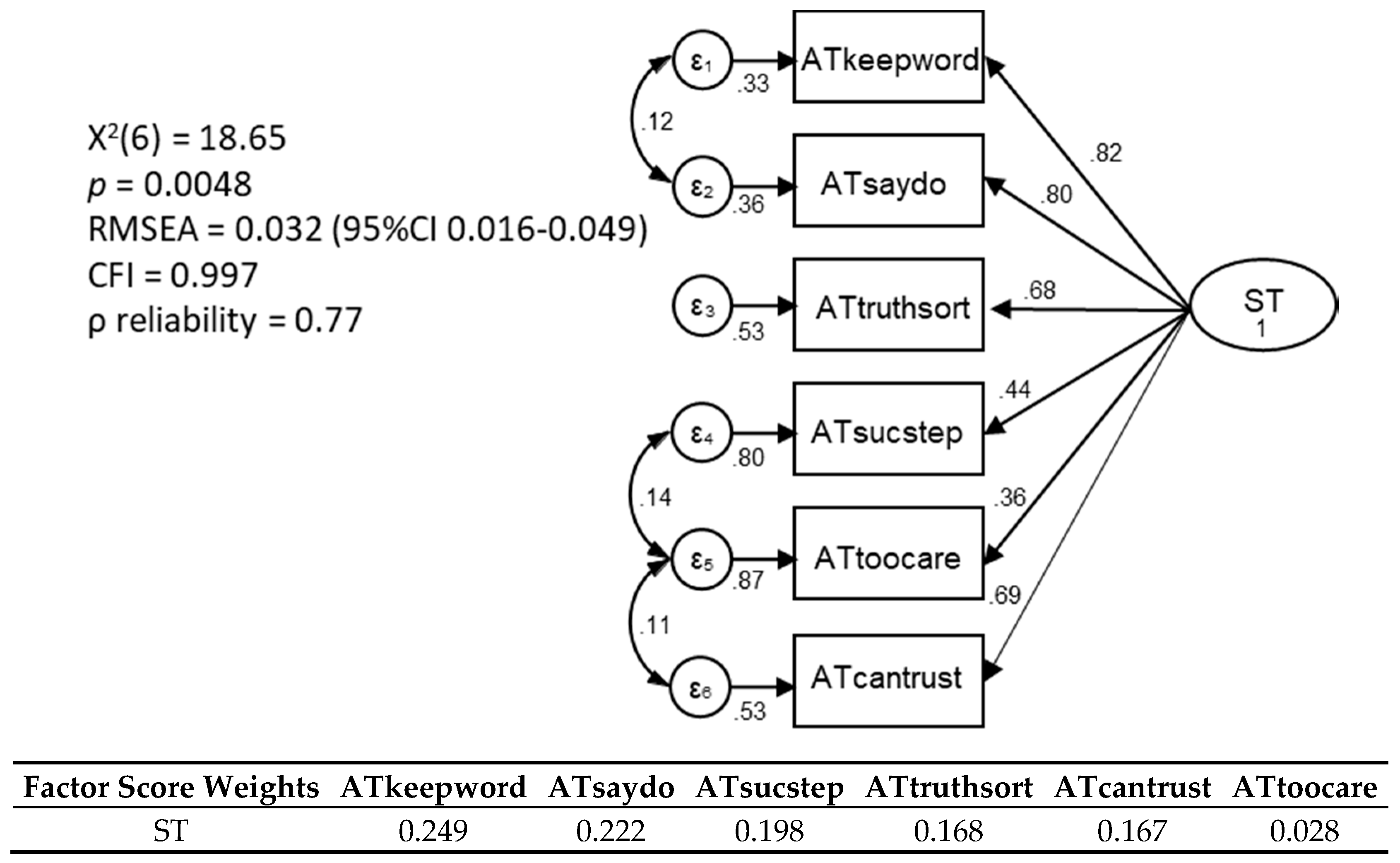

| Social Trust | x1: Most people keep their word | 0.82 | *** | 0.79 | |

| x2: Most people do what they say they’ll do | 0.80 | *** | 0.78 | *** | |

| x3: Most people around here succeed by stepping on others (reverse scored) | 0.44 | *** | 0.32 | *** | |

| x4: Most people tell the truth when they’re sorting out a problem | 0.68 | *** | 0.66 | *** | |

| x5: You can’t be too careful with some people | 0.36 | *** | 0.34 | *** | |

| x6: Most people can be trusted | 0.69 | *** | 0.66 | *** | |

| RMSEA (95% CIs) | 0.032(0.016–0.049) | 0.011(0.000–0.036) | |||

| CFI | 0.997 | 0.998 | |||

| Trait Optimism | x1: Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad | 0.88 | *** | 0.85 | |

| x2: In uncertain times, I always expect the best | 0.78 | *** | 0.74 | *** | |

| x3: If something can go wrong for me, it will (reversed scored) | 0.55 | *** | 0.44 | *** | |

| x4: I’m always optimistic about my future | 0.76 | *** | 0.72 | *** | |

| RMSEA (95% CIs) | 0.029(0.000–0.073) | 0.000(0.000–0.067) | |||

| CFI | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

References

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Red Cross. Relationships Matter: The Application of Social Capital to Disaster Resilience; National Disaster Resilience Roundtable Report; Australian Red Cross: Carlton, Australia, 2012; ISBN 978-0-9875695-0-9. [Google Scholar]

- Price-Robertson, R.; Knight, K. Natural Disasters and Community Resilience: A Framework for Support; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2012; ISBN 978-1-921414-88-6.

- Aldrich, D. (Ed.) Social capital: Its Role in Post-Disaster Recovery. In Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-0-226-01289-6. [Google Scholar]

- Macinko, J.; Starfield, B. The Utility of Social Capital in Research on Health Determinants. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 387–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berry, H.L.; Shipley, M. Longing to Belong: Personal Social Capital and Psychological Distress in an Australian Coastal Region; Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2009; ISBN 978-1-921647-08-6.

- Moore, S.; Kawachi, I. Twenty years of social capital and health research: A glossary. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.L.; Welsh, J.A. Social capital and health in Australia: An overview from the household, income and labour dynamics in Australia survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, N.; Berry, H.; Obrien, L. One-year reciprocal relationship between community participation and mental wellbeing in Australia: A panel analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, F.E. Social capital. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7432-0304-3. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.L. Social capital elite, excluded participators, busy working parents and aging, participating less: Types of community participators and their mental health. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Kawachi, I. The dark side of social capital: A systematic review of the negative health effects of social capital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 194, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uphoff, E.; Pickett, K.E.; Cabieses, B.; Small, N.; Wright, J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: A contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruwys, T.; Berry, H.; Cassells, R.; Duncan, A.; O’Brien, L.; Sage, B.; D’Souza, G. Marginalised Australians: Characteristics and Predictors of Exit over Ten Years 2001–2010; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, M.; Haavik, T.K.; Almklov, P.G. Social Capital and Disaster Resilience. In Proceedings of the 29th European Safety and Reliability Conference (ESREL), Hannover, Germany, 22–26 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harpham, T.; Grant, E.; Thomas, E. Measuring social capital within health surveys: Key issues. Health Policy Plan. 2002, 17, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeri, A.K.; Cruwys, T.; Barlow, F.K.; Stronge, S.; Sibley, C.G. Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2017, 52, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McDermott, B.M.; Berry, H.; Cobham, V. Social connectedness: A potential aetiological factor in the development of child post-traumatic stress disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risk-E Business Consultants Pty Ltd. Independent Review of the NSW State Emergency Service Operational Response—Northern Rivers Floods March 2017. Available online: https://www.ses.nsw.gov.au/media/2344/nsw-ses-operational-response-to-northern-floods-march-2017-final-180717-002.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Longman, J.M.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Matthews, V.; Berry, H.L.; Passey, M.E.; Rolfe, M.; Morgan, G.G.; Braddon, M.; Bailie, R. Rationale and methods for a cross-sectional study of mental health and wellbeing following river flooding in rural Australia, using a community-academic partnership approach. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; Van Horn, R.L.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. A Conceptual Framework to Enhance Community Resilience Using Social Capital. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2015, 45, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, W.; O’Mullan, C. Perceptions of Community Resilience after Natural Disaster in a Rural Australian Town. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 44, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, T.; Stephens, R.E.; Dominey-Howes, D.; Bruce, E.; Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. Disaster declarations associated with bushfires, floods and storms in New South Wales, Australia between 2004 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Household Income and Wealth, Australia, 2015–2016. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/6523.0~2015-16~Main%20Features~Household%20Income%20and%20Wealth%20Distribution~6 (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data by Region. Available online: http://stat.abs.gov.au/itt/r.jsp?databyregion (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Berry, H.L.; Passey, M.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Morgan, G.G.; Pit, S.; Rolfe, M.; Bailie, R.S. Differential Mental Health Impact Six Months After Extensive River Flooding in Rural Australia: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Through an Equity Lens. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, A.J.; Stein, M.B. An abbreviated PTSD checklist for use as a screening instrument in primary care. Behav. Res. Ther. 2005, 43, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S.L.; Berry, H.L.; McDermott, B.M.; Harper, C.M. Summer of sorrow: Measuring exposure to and impacts of trauma after Queensland’s natural disasters of 2010–2011. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, B.; Wong, E.C.; Mao, Z.; Meredith, L.S.; Cassells, A.; Tobin, J.N. Validation of a brief PTSD screener for underserved patients in federally qualified health centers. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spoont, M.; Arbisi, P.; Fu, S.; Greer, N.; Kehle-Forbes, S.; Meis, L.; Rutks, I.; Wilt, T. Screening for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Primary Care: A Systematic Review; VA-ESP Project #09-009; Department of Veteran Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.L. Social capital and mental health among Indigenous Australians, New Australians and Other Australians living in a coastal region. Aust. E-Journal Adv. Ment. Health 2009, 8, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Rodgers, B.; Dear, K. Preliminary development and validation of an Australian community participation questionnaire: Types of participation and associations with distress in a coastal community. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1719–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Mermelstein, R.; Kamarck, T.; Hoberman, H. Interpersonal support evaluation list. In Social Support: Theory, Research and Application; Sarason, I., Sarason, B., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-94-010-8761-2. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R. World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys: 1981–1984, 1990–1993 and 1995–1997; Institute for Social Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.L.; Rodgers, B. Trust and Distress in Three Generations of Rural Australians. Australas. Psychiatry 2003, 11, S131–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, L.L.; Bromiley, P. The Organizational Trust Inventory (OTI): Development and Validation. In Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 302–330. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L. Perceptions about Community Participation and Associations with Psychological Distress. Australas. Epidemiol. 2008, 15, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Acock, A. Discovering Structural Equation Modeling Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-59718-177-8. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, G.G.; Noyan, F. Structural equation modeling with ordinal variables: A large sample case study. Qual. Quant. 2011, 46, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjur, T. Coefficients of Determination in Logistic Regression Models—A New Proposal: The Coefficient of Discrimination. Am. Stat. 2009, 63, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwick, A.; Ansari, Z.; Sullivan, M.; Parsons, L.; McNeil, J. Inequalities in the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: A cross-sectional population-based study in the Australian state of Victoria. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biddle, N. Social Capital and Capabilities—Lecture 11, Measures of Indigenous Wellbeing and Their Determinants Across the Lifecourse; Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M. The vexed link between social capital and social mobility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2015, 50, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickett, M. Examination of How a Culturally-Appropriate Definition of Resilience Affects the Physical and Mental Health of Aboriginal People; The University of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paradies, Y.C.; Cunningham, J. The DRUID study: Exploring mediating pathways between racism and depressive symptoms among Indigenous Australians. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 47, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Corbo, M.; Egan, R. Resilience in the Alice Springs Town Camps. In Promoting Resilience: Responding to Adversity, Vulnerability, and Loss; Thompson, N., Cox, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 95–100. ISBN 978-0-36714-562-0. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, S. An Aboriginal Perspective on Resilience: Resilience needs to be defined from an Indigenous context. Aborig. Isl. Health Work. J. 2007, 31, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Torche, F.; Valenzuela, E. Trust and reciprocity: A theoretical distinction of the sources of social capital. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2011, 14, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, K.; Casey, D.; Ward, J.S. First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 213, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, C.P.; Johnston, F.H.; Berry, H.L.; McDonnell, J.; Yibarbuk, D.; Gunabarra, C.; Mileran, A.; Bailie, R.S. Healthy country, healthy people: The relationship between Indigenous health status and “caring for country”. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, H.; Butler, J.R.A.; Burgess, C.P.; King, U.G.; Tsey, K.; Cadet-James, Y.L.; Rigby, C.W.; Raphael, B. Mind, body, spirit: Co-benefits for mental health from climate change adaptation and caring for country in remote Aboriginal Australian communities. N. S. W. Public Health Bull. 2010, 21, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodward, E.; Hill, R.; Harkness, P.; Archer, R. Our Knowledge Our Way in Caring for Country: Indigenous-Led Approaches to Strengthening and Sharing Our Knowledge for Land and Sea Management; Best Practice Guidelines from Australian Experiences NAILSMA and CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4863-1408-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hefler, M.; Kerrigan, V.; Henryks, J.; Freeman, B.; Thomas, D.P. Social media and health information sharing among Australian Indigenous people. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hookway, N.; Neeves, B.B.; Franklin, A.; Patulny, R. Loneliness and love in late modernity: Sites of tension and resistance. In Emotions in Late Modernity; Patulny, R., Bellocchi, A., Olson, R., Khorana, S., McKenzie, J., Peterie, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 83–97. ISBN 978-1-351-13331-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nowland, R.; Necka, E.A.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness and Social Internet Use: Pathways to Reconnection in a Digital World? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 13, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dufty, N. Using social media to build community disaster resilience Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2012, 27, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lancee, B.; Van De Werfhorst, H.G. Income inequality and participation: A comparison of 24 European countries. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, M.J.; Makwarimba, E.; Reutter, L.I.; Veenstra, G.; Raphael, D.; Love, R. Poverty, Sense of Belonging and Experiences of Social Isolation. J. Poverty 2009, 13, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, P.V.; Andersen, P.T.; Curtis, T. Social relations and experiences of social isolation among socially marginalized people. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2012, 29, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life, 2nd ed.; John Murray Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-47368-432-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carbone, E.G.; Echols, E.T. Effects of optimism on recovery and mental health after a tornado outbreak. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongsavan, P.; Chey, T.; Bauman, A.; Brooks, R.; Silove, D. Social capital, socio-economic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.M.; Stillman, T.F.; Hicks, J.A.; Kamble, S.; Baumeister, R.F.; Fincham, F.D. To Belong Is to Matter. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cox, R.S.; Perry, K.-M.E. Like a Fish Out of Water: Reconsidering Disaster Recovery and the Role of Place and Social Capital in Community Disaster Resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 48, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsini, S.; Mills, J.; Usher, K. Solastalgia: Living with the Environmental Damage Caused by Natural Disasters. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2014, 29, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, H.J. Disaster resilience in a flood-impacted rural Australian town. Nat. Hazards 2013, 71, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.; Walmsley, J.; Argent, N.; Baum, S.; Bourke, L.; Martin, J.; Pritchard, B.; Sorensen, T. Rural Community and Rural Resilience: What is important to farmers in keeping their country towns alive? J. Rural. Stud. 2012, 28, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Baum, F.; Darmawan, I.G.N.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Bentley, R. Social capital and health in rural and urban communities in South Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2009, 33, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; Kokic, P.; Crimp, S.; Martin, P.; Meinke, H.; Howden, S.; De Voil, P.; Nidumolu, U. The vulnerability of Australian rural communities to climate variability and change: Part II—Integrating impacts with adaptive capacity. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, T.R.; Komproe, I.H. The mechanisms that associate community social capital with post-disaster mental health: A multilevel model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. Mental Health Services in Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health-services-in-australia (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Shorthouse, M.; Stone, L. Inequity amplified: Climate change, the Australian farmer, and mental health. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, M.L.; Creamer, M.C.; Parslow, R.; Elliott, P.; Holmes, A.C.N.; Ellen, S.; Judson, R.; McFarlane, A.C.; Silove, D.; Bryant, R.A. A predictive screening index for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following traumatic injury. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, B.M.; Palmer, L.J. Postdisaster Emotional Distress, Depression and Event-Related Variables: Findings across Child and Adolescent Developmental Stages. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Community Participation | ||

| Informal Social Connectedness | I make time to keep in touch with my friends; I chat with my neighbours when I see them; I spend time with extended family members (relatives who don’t live with me) | Australian Community Participation Questionnaire (ACPQ) [33] |

| Social Media Engagement | I am active on social media (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram) | New |

| Civic Engagement | I take part in community-based clubs or associations (e.g., Rotary, CWA, book club, Lions); I go to arts or cultural events; I attend community events such as farmers’ markets, festivals and shows; I take part in sports activities or groups; I volunteer locally (e.g., Meals on Wheels, school fete, Rural Fire Service); I attend worship services or go to prayer meetings | ACPQ [33] |

| Political Participation | I get involved with political activities (e.g., through interest groups, public meetings, rallies) | Adapted from ACPQ [33] |

| Perceptions of Participation | I enjoy the time I spend with others socially; I would like to spend more time with others socially | Adapted from Berry, 2008 [39] |

| Construct | Personal Social Cohesion | Source |

| Sense of Belonging | When I feel lonely, there are several people I could call and talk to; I have family or friends I can confide in; I feel that I’m on the fringe in my circle of friends; I don’t often get invited to do things with others; There are people outside my household who can offer help in a crisis. | Adapted from Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) [34] |

| Feelings of Belonging | I feel like an outsider; I feel that I belong; I feel included. | Adapted from Berry (unpublished) |

| Social Trust | Most people keep their word; Most people do what they say they’ll do; Most people around here succeed by stepping on others; Most people tell the truth when they’re sorting out a problem; You can’t be too careful with some people; Most people can be trusted. | Adapted by Berry & Rodgers [36] from Organisational Trust Inventory (OTI) [37] & World Values Survey (WVS) [35] |

| Generalised Reciprocity | Most people try to be helpful; Most people look out for themselves | Adapted from WVS [35] |

| Trait Optimism | Overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad; In uncertain times, I always expect the best; If something can go wrong for me, it will; I’m always optimistic about my future | Selected from Life Orientation Test – Revised [38] |

| Construct | Factor Loadings (Range) | CFI | RMSEA | 95%CI | ρ Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal Social Connectedness | 0.60–0.83 | 1.000 | 0.000 | (0.000–0.040) | 0.72 |

| Civic Engagement | 0.45–0.81 | 0.991 | 0.058 | (0.041–0.078) | 0.73 |

| Sense of Belonging | 0.43–0.86 | 0.997 | 0.048 | (0.028–0.071) | 0.75 |

| Feelings of belonging | 0.67–0.88 | 1.000 | 0.000 | (0.000–0.050) | 0.85 |

| Social Trust | 0.36–0.82 | 0.997 | 0.032 | (0.016–0.049) | 0.77 |

| Trait Optimism | 0.55–0.88 | 1.000 | 0.029 | (0.000–0.073) | 0.82 |

| Characteristic | Category | Aboriginal Respondents (n = 67; 3.5%) | Respondents in Financial Hardship (n = 287; 15.2%) | Other Respondents (n = 1534; 81.3%) | Total (n = 1888) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 46.5 ## | 14.0 | 48.8 ### | 13.0 | 52.4 | 14.4 | 51.7 | 14.3 | |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Female | 49 | 73.1 | 197 | 68.6 | 1058 | 69.0 | 1304 | 69.1 |

| Employment | Not in employment ^ | 15 | 22.4 *** | 132 | 46.0 *** | 144 | 9.4 | 291 | 15.4 |

| Education | University level | 20 | 29.9 ## | 88 | 30.7 ### | 735 | 47.9 | 843 | 44.7 |

| Relationship status | Single | 31 | 46.3 *** | 178 | 62.0 *** | 401 | 26.1 | 610 | 32.3 |

| Mental health outcomes | Ongoing distress | 28 | 41.8 *** | 92 | 32.1 *** | 305 | 19.9 | 425 | 22.5 |

| Probable PTSD | 24 | 35.8 *** | 94 | 32.8 *** | 173 | 11.3 | 291 | 15.4 | |

| Social Capital Construct | Aboriginal Respondents (n = 67) | Financial Hardship Respondents (n = 287) | Other Respondents (n = 1534) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Med. | IQR | Med. | IQR | Med. | IQR | |||

| Community participation (score range 1–7) | ||||||||

| Informal Social Connectedness | 5.3 | (4.0–6.0) | ** | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | *** | 5.7 | (4.7–6.0) |

| Social Media Engagement | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (3.0–6.0) | ||

| Civic Engagement | 4.0 | (2.8–5.0) | 4.0 | (3.0–4.8) | *** | 4.2 | (3.2–5.2) | |

| Religious Engagement | 2.0 | (1.0–4.0) | 1.0 | (1.0–3.0) | * | 2.0 | (1.0–4.0) | |

| Political Participation | 4.0 | (1.0–5.0) | 4.0 | (2.0–5.0) | 3.0 | (2.0–5.0) | ||

| Breadth of participation (0–11) | 6.0 | (4.0–7.0) | 5.0 | (3.0–7.0) | *** | 6.0 | (4.0–8.0) | |

| Perceptions of participation (1–7) | ||||||||

| Enjoyment (enjoy the time spent socially) | 6.0 | (5.0–6.0) | ** | 6.0 | (5.0–6.0) | *** | 6.0 | (5.0–7.0) |

| Sufficiency (desire to spend more time socially) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | ||

| Personal Social Cohesion (1–7) | ||||||||

| Sense of Belonging | 4.8 | (4.0–6.0) | ** | 4.8 | (4.0–5.6) | *** | 5.4 | (4.6–6.0) |

| Feelings of Belonging | 5.0 | (3.3–6.0) | * | 4.3 | (3.3–5.7) | *** | 5.3 | (4.3–6.0) |

| Social Trust | 4.2 | (3.3–4.8) | *** | 4.0 | (3.5–4.7) | *** | 4.7 | (4.0–5.2) |

| Reciprocity—People try to help | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (5.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (5.0–6.0) | ||

| Reciprocity—People look after themselves | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 | (4.0–6.0) | ||

| Optimism | 4.5 | (3.5–5.8) | *** | 4.5 | (3.8–5.3) | *** | 5.3 | (4.3–5.8) |

| Social Capital Construct | Aboriginal Respondents (n = 67) | Financial Hardship Respondents (n = 287) | Other Respondents (n = 1534) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing Distress | PTSD | Ongoing Distress | PTSD | Ongoing Distress | PTSD | |||||||

| Flood Exposure # | 0.39 | *** | 0.22 | * | 0.29 | *** | 0.24 | *** | 0.31 | *** | 0.26 | *** |

| Community Participation | ||||||||||||

| Informal Social Connectedness | −0.04 | −0.13 | −0.01 | −0.15 | ** | −0.06 | * | −0.09 | *** | |||

| Civic Engagement | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.001 | −0.11 | * | −0.03 | −0.07 | ** | ||||

| Social Media Engagement | −0.25 | * | −0.25 | * | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||||

| Religious Engagement | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.08 | 0.001 | −0.04 | ||||||

| Political Participation | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | ||||||

| Breadth of Participation | −0.03 | −0.18 | −0.04 | −0.11 | * | −0.03 | −0.09 | *** | ||||

| Perceptions of Participation | ||||||||||||

| Enjoyment of time socialising | −0.24 | * | −0.23 | * | −0.08 | −0.17 | ** | −0.14 | *** | −0.20 | *** | |

| Sufficiency of time socialising | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Personal Social Cohesion | ||||||||||||

| Sense of Belonging | −0.23 | * | −0.38 | *** | −0.12 | * | −0.29 | *** | −0.14 | *** | −0.17 | *** |

| Feeling of Belonging | −0.29 | ** | −0.42 | *** | −0.15 | ** | −0.35 | *** | −0.13 | *** | −0.21 | *** |

| Social Trust | −0.23 | * | −0.34 | ** | −0.08 | −0.18 | ** | −0.11 | *** | −0.14 | *** | |

| Reciprocity—people try to help | −0.22 | −0.39 | *** | −0.03 | −0.17 | ** | −0.09 | *** | −0.11 | *** | ||

| Reciprocity—people look after themselves | 0.18 | 0.27 | * | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.05 | * | 0.08 | *** | |||

| Optimism | −0.21 | * | −0.24 | * | −0.19 | *** | −0.24 | *** | −0.16 | *** | −0.20 | *** |

| Aboriginal Respondents (n = 66) | Financial Hardship Respondents † (n = 280) | Other Respondents (n = 1477) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Block | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D |

| 1. Flood Exposure (CEI) | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | ||||||

| 2.73 | (1.52–4.91) | **^ | 1.86 | (1.46–2.38) | *** ^ | 2.15 | (1.90–2.42) | *** ^ | ||||

| 2. Community Participation | ||||||||||||

| 2 A. Type & extent of participation | 0.01 | 0.15 | ||||||||||

| Informal Social Connectedness | - | - | 0.86 | (0.77–0.97) | * | |||||||

| 2 B. Perceptions of participation | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Enjoy time spent socially | 0.59 | (0.37–0.95) | * ^ | - | 0.76 | (0.67–0.87) | *** | |||||

| 3. Personal Social Cohesion | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| Sense of Belonging | - | - | 0.81 | (0.68–0.96) | * ^ | |||||||

| Optimism | - | 0.62 | (0.48–0.79) | *** ^ | 0.74 | (0.64–0.86) | ***^ | |||||

| Aboriginal Respondents (n = 67) | Financial Hardship Respondents † (n = 283) | Other Respondents (n = 1463) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Block | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D | aOR | (95%CI) | ∆D | D |

| Socio-demographic Factors | 0.12 | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Education (non-university level) | 4.56 | (1.12–18.60) * | - | 1.68 | (1.20–2.35) ** | |||||||

| Employment (not in employment) | - | - | 2.08 | (1.31–3.29) ** | ||||||||

| Relationship status (single) | - | - | 1.44 | (1.02–2.05) * | ||||||||

| 1. Flood Exposure (CEI) | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 1.69 | (1.06–2.72) * | 1.63 | (1.30–2.05) ***^ | 2.22 | (1.91–2.58) ***^ | |||||||

| 2. Community Participation | ||||||||||||

| 2 A. Type and extent of participation | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Informal Social Connectedness | 0.53 | (0.31–0.92) * | 0.71 | (0.56–0.89) ** | 0.72 | (0.63–0.83) *** | ||||||

| 2 B. Perceptions of participation | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| Enjoy time spent socially | - | 0.76 | (0.61–0.95) * | 0.60 | (0.51–0.70) ***^ | |||||||

| Sufficient time socialising | - | 1.30 | (1.08–1.56) ** | 1.16 | (1.02–1.32) * | |||||||

| 3. Personal Social Cohesion | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.24 | ||||||

| Feeling of Belonging | 0.41 | (0.23–0.71) ** ^ | 0.48 | (0.37–0.62) *** ^ | 0.65 | (0.55–0.76) ***^ | ||||||

| Optimism | - | - | 0.67 | (0.55–0.81) ***^ | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matthews, V.; Longman, J.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Braddon, M.; Passey, M.; Bailie, R.S.; Berry, H.L. Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207676

Matthews V, Longman J, Bennett-Levy J, Braddon M, Passey M, Bailie RS, Berry HL. Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207676

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatthews, Veronica, Jo Longman, James Bennett-Levy, Maddy Braddon, Megan Passey, Ross S. Bailie, and Helen L. Berry. 2020. "Belonging and Inclusivity Make a Resilient Future for All: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Post-Flood Social Capital in a Diverse Australian Rural Community" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207676