Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values

Abstract

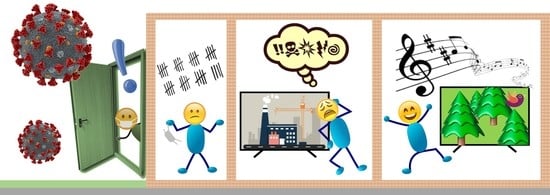

:1. Introduction

- The isolation caused by the lockdown might have raised the levels of anxiety (in individuals not affected by anxiety disorders).

- This extreme condition enabled us to study experimentally the anxiety level after excluding confounding factors of normal everyday life, such as social interaction or events or activities (sport, cultural, etc.).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Self-Report Questionnaires

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruber, J.; Prinstein, M.J.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Albano, A.M.; Aldao, A.; Borellui, J.L.; Clark, L.A.; Davila, J.; Forbes, E.E.; Gee, D.G.; et al. Clinical Psychological Science’s Call To Action in the Time of COVID-19. Clin. Psychol. Sci. COVID-19 2020, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 52, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, J.H.; Xu, Y.F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinic, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of Economic Uncertainty on Mental Health in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context: Social Identity Disturbance, Job Uncertainty and Psychological Well-Being Model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Kelifa, M.; He, Q.; Wang, P. COVID-19 related depression and anxiety among quarantined respondents. Psychol. Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-yoku (Forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazon, S.S.; Sidenius, U.; Poulsen, D.V.; Gramkow, M.C.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Psycho-physiological stress recovery in outdoor nature-based interventions: A systematic review of the past eight years of research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on human health: A review of the literature. Sante Publique 2019, 31, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuyashiki, A.; Tabuchi, K.; Norikoshi, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Oriyama, S. A comparative study of the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku) on working age people with and without depressive tendencies. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, M.H.; Chang, M.C.; Lee, S.J. The effects of forest therapy on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic stroke. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, M.R.; Washburn, K. A Review of Field Experiments on the Effect of Forest Bathing on Anxiety and Heart Rate Variability. Glob. Adv. Heal. Med. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, M.; Barbieri, G.; Donelli, D. Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarker: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielinis, E.; Jaroszewska, A.; Łukowski, A.; Takayama, N. The Effects of a Forest Therapy Programme on Mental Hospital Patients with Affective and Psychotic Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, Y.; Yan, Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y. Medical empirical research on forest bathing (Shinrin-yoku): A systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of nature therapy: A review of the research in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Miyazaki, Y. Trends in research related to “shinrin-yoku” (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing) in Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Bartolini, G.; Zabini, F. Temporal and Spatial Variability of Volatile Organic Compounds in the Forest Atmosphere. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Nakadai, A.; Matsushima, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Krensky, A.; Kawada, T.; Morimoto, K. Phytoncides (wood essential oils) induce human natural killer cell activity. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2006, 28, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakayama, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kawada, T.; Park, B.J.; et al. Effect of phytoncide from trees on human natural killer cell function. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2009, 22, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Lee, C.J. Sleep-enhancing Effects of Phytoncide via Behavioral, Electrophysiological, and Molecular Modeling Approaches. Exp. Neurobiol. 2020, 29, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of visual stimulation with forest imagery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Kort, Y.A.W.; Meijnders, A.L.; Sponselee, A.A.G.; IJsselsteijn, W.A. What’s wrong with virtual trees? Restoring from stress in a mediated environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Koole, S.L.; van der Wulp, N.Y. Environmental preference and restoration: (How) are they related? J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, I.C.; Tsai, Y.P.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, J.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Hung, S.H.; Sullivan, W.C.; Tang, H.F.; Chang, C.Y. Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to analyze brain region activity when viewing landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 162, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, M.; Nogaki, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Stone, T.E.; Kobayashi, T. Individual reactions to viewing preferred video representations of the natural environment: A comparison of mental and physical reactions. Japan J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 14, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Mimnaugh, K.J.; Van Riper, C.J.; Laurent, H.K.; Lavalle, S.M. Can Simulated Nature Support Mental Health? Comparing Short, Single-Doses of 360-Degree Nature Videos in Virtual Reality with the Outdoors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Depledge, M.H.; Stone, R.J.; Bird, W.J. Can natural and virtual environments be used to promote improved human health and wellbeing? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4660–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.A.; Rogers, K.; Buckley, T.J.; Schnoor, J.L. Advancing Environmental Epidemiology to Assess the Beneficial Influence of the Natural Environment on Human Health and Well-Being. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9545–9555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bang, K.S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.K.; Kang, K.I.; Jeong, Y. The effects of a health promotion program using urban forests and nursing student mentors on the perceived and psychological health of elementary school children in vulnerable populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saraev, V.; O’Brien, L.; Valatin, G.; Atkinson, M.; Bursnell, M. Scoping Study on Valuing Mental Health Benefits of Forests; The Research Agency of the Forestry Commision: Edinburgh, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mipaaf—Consultazione Pubblica—Strategia Forestale Nazionale per il Settore Forestale e le sue Filiere. Available online: https://www.politicheagricole.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/15339 (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Dodev, Y.; Zhiyanski, M.; Glushkova, M.; Shin, W.S. Forest welfare services—The missing link between forest policy and management in the EU. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V. The diagnosis and drug treatment of anxiety disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1983, 7, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, A.A.; Sheehan, D.V.; Jones, K.J. Dental anxiety—the development of a measurement model. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1986, 73, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Sato, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest)—Using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.J.; Ishii, H.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest) in an old-growth broadleaf forest in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Janeczko, E.; Bielinis, E.; Wójcik, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Kędziora, W.; Łukowski, A.; Elsadek, M.; Szyc, K.; Janeczko, K. When urban environment is restorative: The effect of walking in suburbs and forests on psychological and physiological relaxation of young Polish adults. Forests 2020, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calfapietra, C.; Fares, S.; Manes, F.; Morani, A.; Sgrigna, G.; Loreto, F. Role of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds (BVOC) emitted by urban trees on ozone concentration in cities: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 183, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Daily, G.C. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1249, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment Design Guidelines View Project Healthcare Architecture View Project. In Human Behavior and Environment; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chiang, Y. The Influence of Forest Resting Environments on Stress Using Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schebella, M.F.; Weber, D.; Schultz, L.; Weinstein, P. The nature of reality: Human stress recovery during exposure to biodiverse, multisensory virtual environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’connor, R.C.; Perry, H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohly, H.; White, M.P.; Wheeler, B.W.; Bethel, A.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Nikolaou, V.; Garside, R. Attention Restoration Theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 2016, 19, 305–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leung, K.; Wu, J.T.; Liu, D.; Leung, G.M. First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: A modelling impact assessment. Lancet 2020, 395, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litleskare, S.; Macintyre, T.E.; Calogiuri, G. Enable, reconnect and augment: A new era of virtual nature research and application. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mattila, O.; Korhonen, A.; Poyry, D.E.; Hauru, K.; Holopainen, J.; Parvinen, P. Restoration in a virtual reality forest environment. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of forest-related visual, olfactory, and combined stimuli on humans: An additive combined effect. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A comparison of the restorative effect of a natural environment with that of a simulated natural environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, M.P.; Yeo, N.L.; Vassiljev, P.; Lundstedt, R.; Wallergård, M.; Albin, M.; Lõhmus, M. A prescription for “nature”—The potential of using virtual nature in therapeutics. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 3001–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Forest Condition (n = 41) | Urban Condition (n = 34) | Statistical Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean and SD) | 45.6 (11.8) | 49.3 (14.5) | t(73) = 1.22, p = 0.227 |

| Gender | 56% female | 62% female | χ2 (1) = 0.24, p = 0.620 |

| Residence | North: 25% Center: 63% South: 5% Abroad: 7% | North: 32% Center: 62% South: 6% Abroad: - | χ2 (3) = 2.95, p = 0.399 |

| External space in the residence/could see a green area outside | 95% | 94% | χ2 (1) = 0.04, p = 0.847 |

| Education | High school: 32% Italian Laurea (5 yrs) or higher: 68% | High school: 29% Italian Laurea (5 yrs) or higher: 71% | χ2 (1) = 0.05, p = 0.830 |

| Experience with COVID-19 | 51% | 38% | χ2 (1) = 1.26, p = 0.261 |

| Forced isolation due to direct contact with COVID-19 | 5% | 6% | χ2 (1) = 0.04, p = 0.847 |

| Chronic disease | 27% | 21% | χ2 (1) = 0.40, p = 0.529 |

| No regular practice of sports | 32% | 35% | χ2 (1) = 0.11, p = 0.743 |

| Impossibility to perform his/her own sport inside the residence | 65% | 63% | χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.908 |

| Previous experience with meditation | 44% | 38% | χ2 (1) = 0.25, p = 0.620 |

| Previous experience with Yoga | 41% | 29% | χ2 (1) = 1.17, p = 0.279 |

| Day | Measure | Forest | Urban | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD/SEM | Range | Mean | SD/SEM | Range | ||

| 1 | Pre | 5.20 | 5.22/.76 | 0–22 | 4.47 | 4.32/0.83 | 0–17 |

| Post | 3.15 | 3.45/.59 | 0–15 | 4.41 | 4.14/0.65 | 0–14 | |

| 2 | Pre | 5.05 | 5.11/0.67 | 0–19 | 3.18 | 2.96/0.73 | 0–11 |

| Post | 3.17 | 3.25/0.50 | 0–13 | 3.35 | 3.09/0.55 | 0–15 | |

| 3 | Pre | 3.61 | 3.63/0.54 | 0–18 | 3.12 | 3.23/0.59 | 0–17 |

| Post | 2.73 | 2.81/0.55 | 0–13 | 3.94 | 4.20/0.60 | 0–22 | |

| 4 | Pre | 3.85 | 4.17/0.58 | 0–18 | 3.00 | 3.03/0.63 | 0–14 |

| Post | 2.83 | 2.73/0.51 | 0–11 | 4.09 | 3.77/0.56 | 0–17 | |

| 5 | Pre | 4.54 | 6.33/0.85 | 0–21 | 2.82 | 4.13/0.93 | 0–21 |

| Post | 3.07 | 3.76/0.59 | 0–17 | 3.12 | 3.79/0.65 | 0–16 | |

| Day | Main Effect of Condition | Main Effect of Pre-Post Treatment | Interaction Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F(1,73) = 0.08, p = 0.776 | F(1,73) = 9.25, p = 0.003 | F(1,73) = 8.25, p = 0.005 |

| 2 | F(1,73) = 1.10, p = 0.299 | F(1,73) = 6.45, p = 0.013 | F(1,73) = 9.40, p = 0.003 |

| 3 | F(1,73) = 0.21, p = 0.649 | F(1,73) = 0.02, p = 0.887 | F(1,73) = 19.91, p < 0.001 |

| 4 | F(1,73) = 0.07, p = 0.789 | F(1,73) = 0.01, p = 0.913 | F(1,73) = 13.77, p < 0.001 |

| 5 | F(1,73) = 0.64, p = 0.425 | F(1,73) = 3.49, p = 0.066 | F(1,73) = 7.89, p = 0.006 |

| Measure | Condition | One-Week Pre-Post Value Mean (sd, Range) | Paired-Sample Student’s t |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAI-Y1 | Forest | 42.5 (13.1, 21–62) – 43.1 (13.3, 22–72) | t(35) = −0.59, p = 0.556 |

| Urban | 39.4 (10.6, 21–68) – 39.8 (11.4, 21–69) | t(27) = −0.32, p = 0.748 | |

| STAI-Y2 | Forest | 39.3 (10.4, 23–60) – 40.5 (11.2, 22–66) | t(35) = −1.19, p = 0.241 |

| Urban | 39.0 (11.8, 21–61) – 39.1 (12.1, 20–67) | t(27) = −0.11, p = 0.915 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zabini, F.; Albanese, L.; Becheri, F.R.; Gavazzi, G.; Giganti, F.; Giovanelli, F.; Gronchi, G.; Guazzini, A.; Laurino, M.; Li, Q.; et al. Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218011

Zabini F, Albanese L, Becheri FR, Gavazzi G, Giganti F, Giovanelli F, Gronchi G, Guazzini A, Laurino M, Li Q, et al. Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218011

Chicago/Turabian StyleZabini, Federica, Lorenzo Albanese, Francesco Riccardo Becheri, Gioele Gavazzi, Fiorenza Giganti, Fabio Giovanelli, Giorgio Gronchi, Andrea Guazzini, Marco Laurino, Qing Li, and et al. 2020. "Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 8011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218011

APA StyleZabini, F., Albanese, L., Becheri, F. R., Gavazzi, G., Giganti, F., Giovanelli, F., Gronchi, G., Guazzini, A., Laurino, M., Li, Q., Marzi, T., Mastorci, F., Meneguzzo, F., Righi, S., & Viggiano, M. P. (2020). Comparative Study of the Restorative Effects of Forest and Urban Videos during COVID-19 Lockdown: Intrinsic and Benchmark Values. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8011. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218011