Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ambient Particulate Matter (PM2.5)

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatments

2.3. Viability Assay

2.4. Annexin V Staining

2.5. Caspase-3/7—Activity Assay

2.6. Intracellular ROS

2.7. Preparation of Cell Lysates

2.8. Immunoblotting

2.9. Microarray Analysis

2.10. Measurement of Intracellular Glutathione Levels

2.11. Cell Morphology

2.12. Cellular Doxorubicin Content

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of PM2.5 from Biomass Combustion

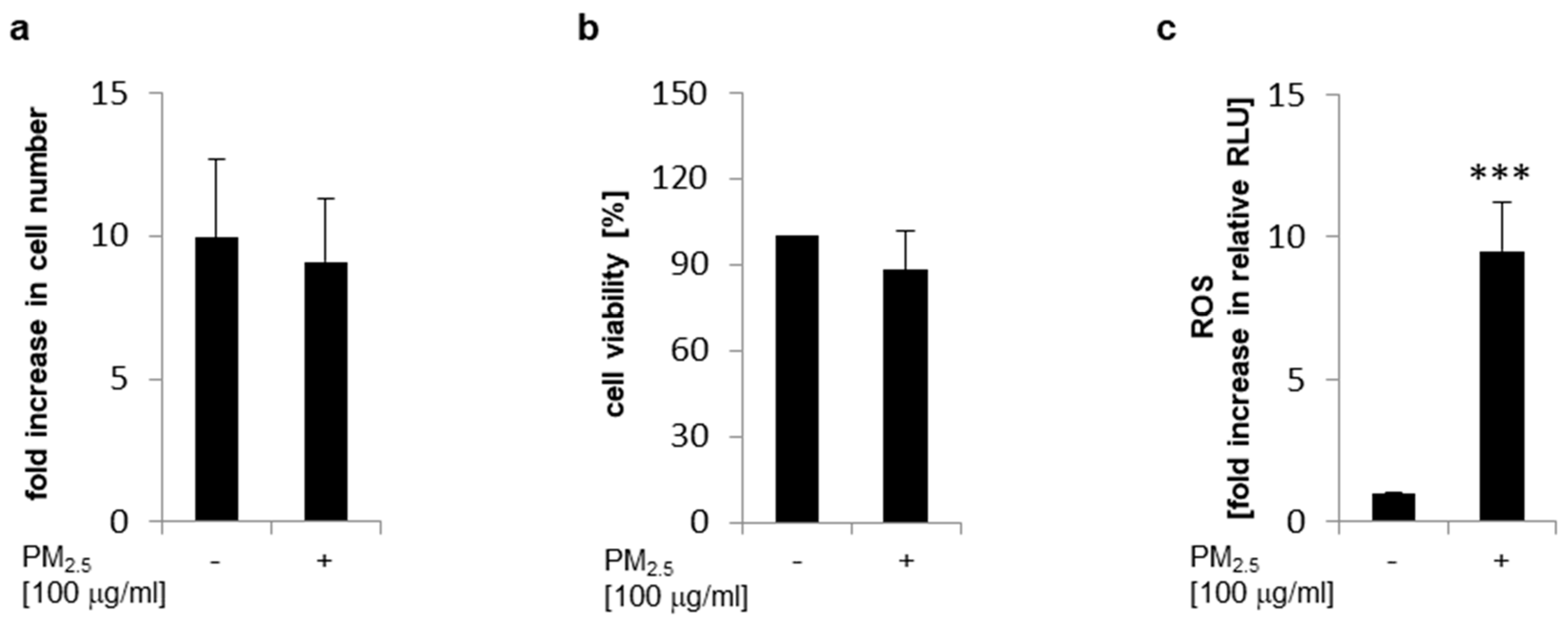

3.2. Cellular Viability and ROS Generation

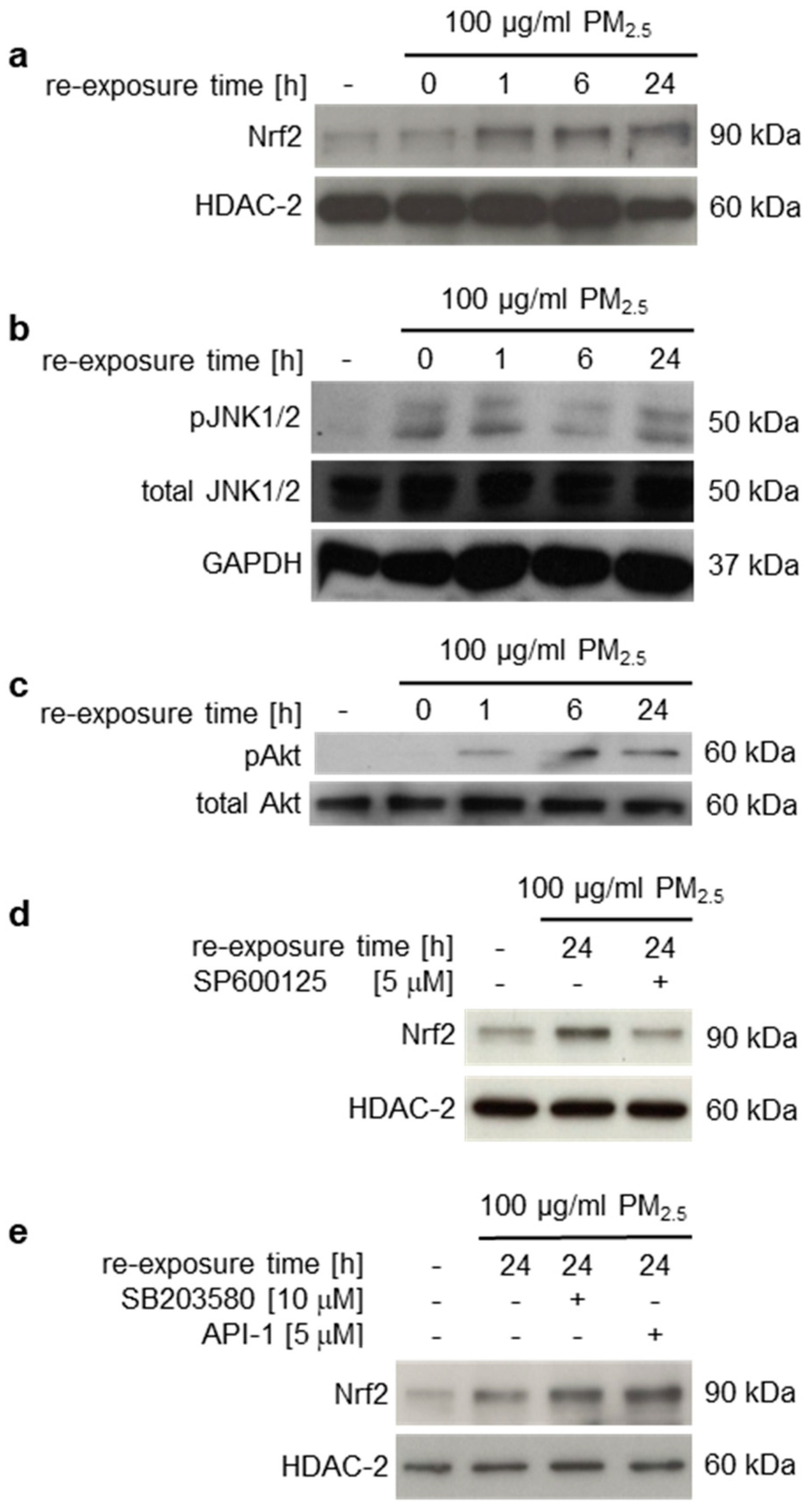

3.3. Induction of Nrf2

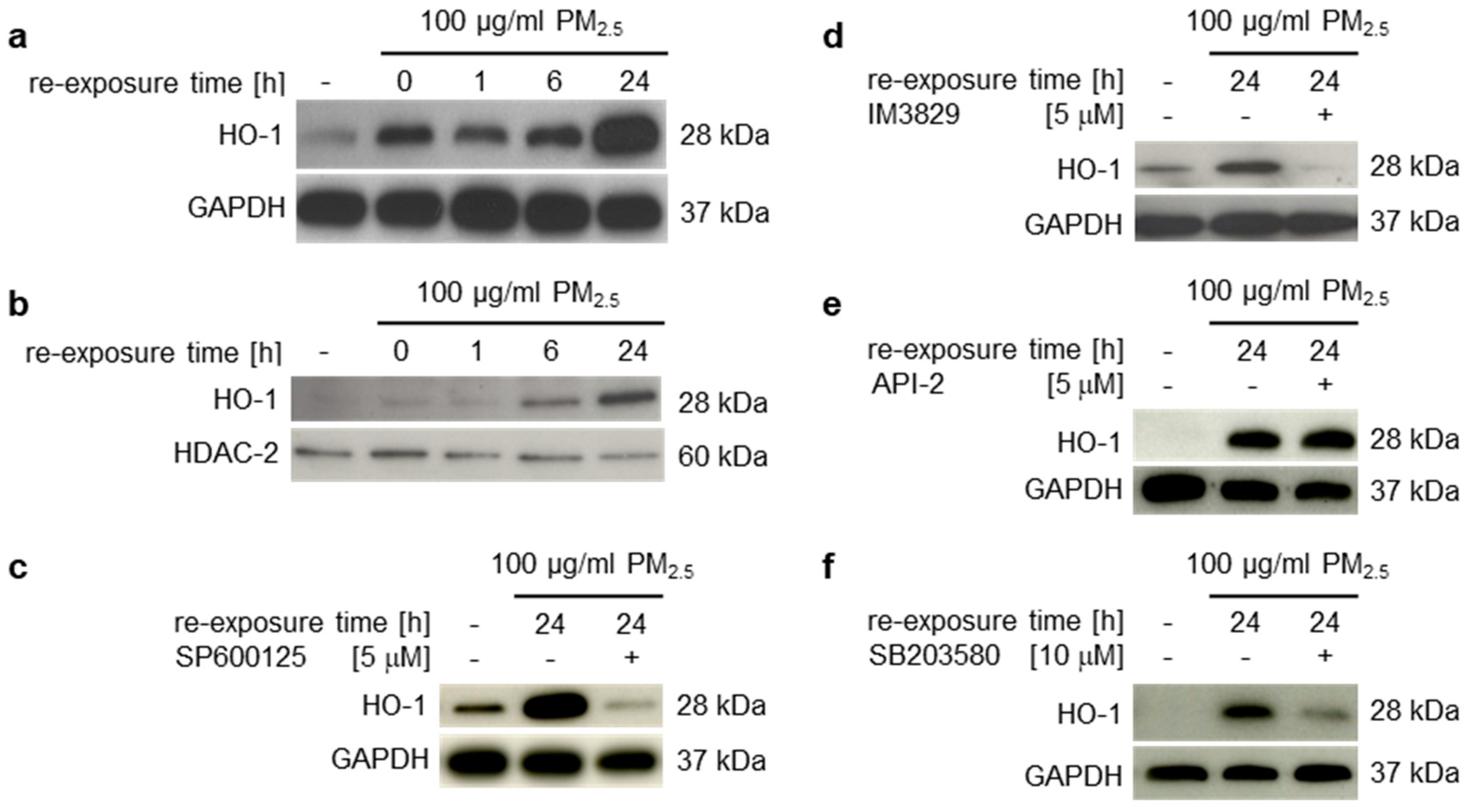

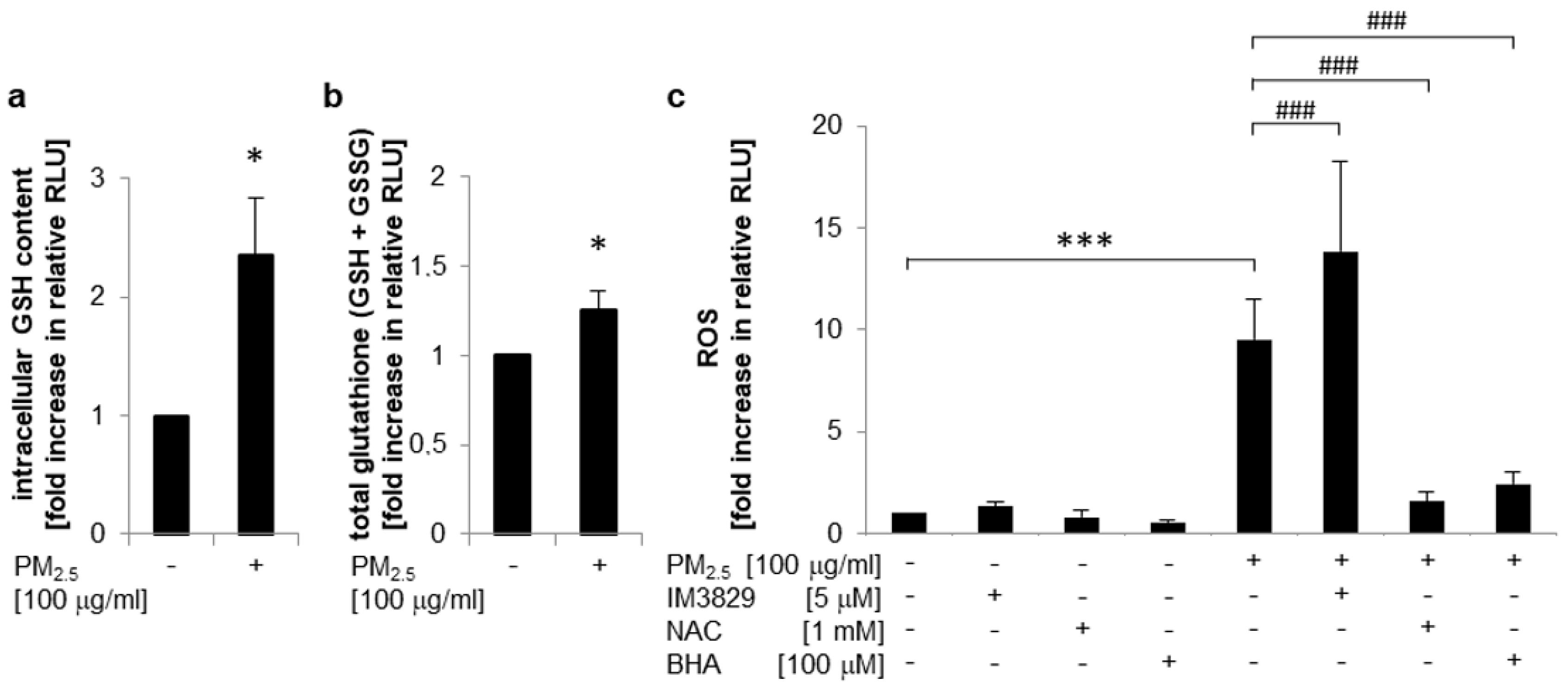

3.4. Induction of Nrf2 Downstream Target Genes and Antioxidant Response Prevent Induction of Inflammatory Mediators

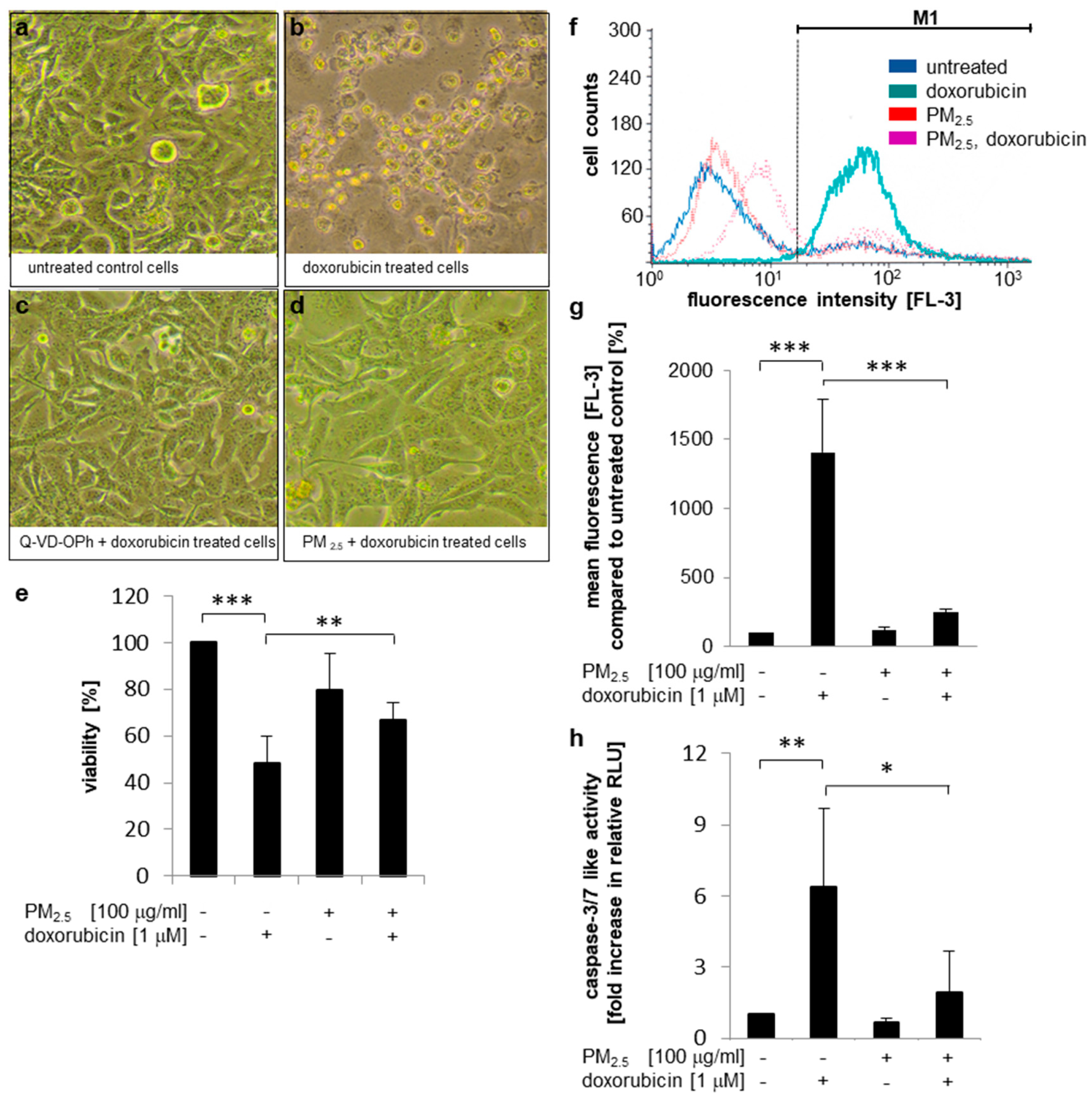

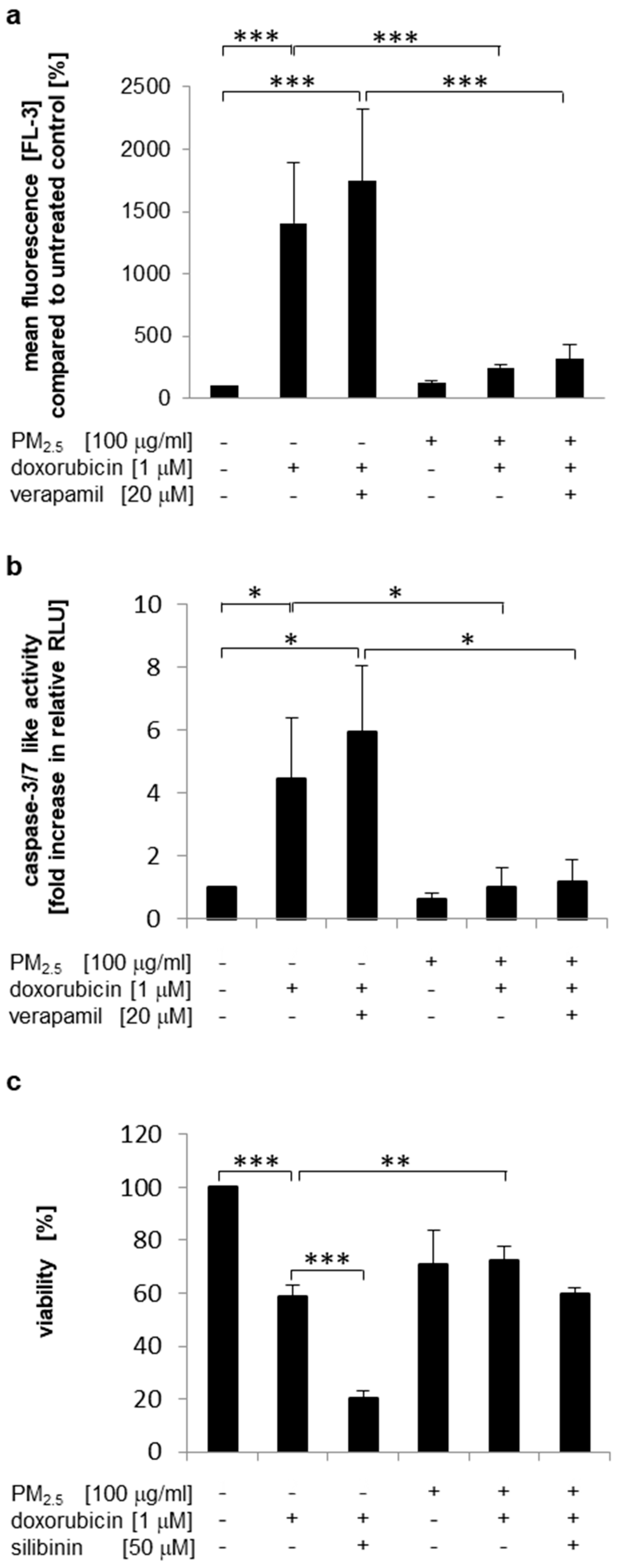

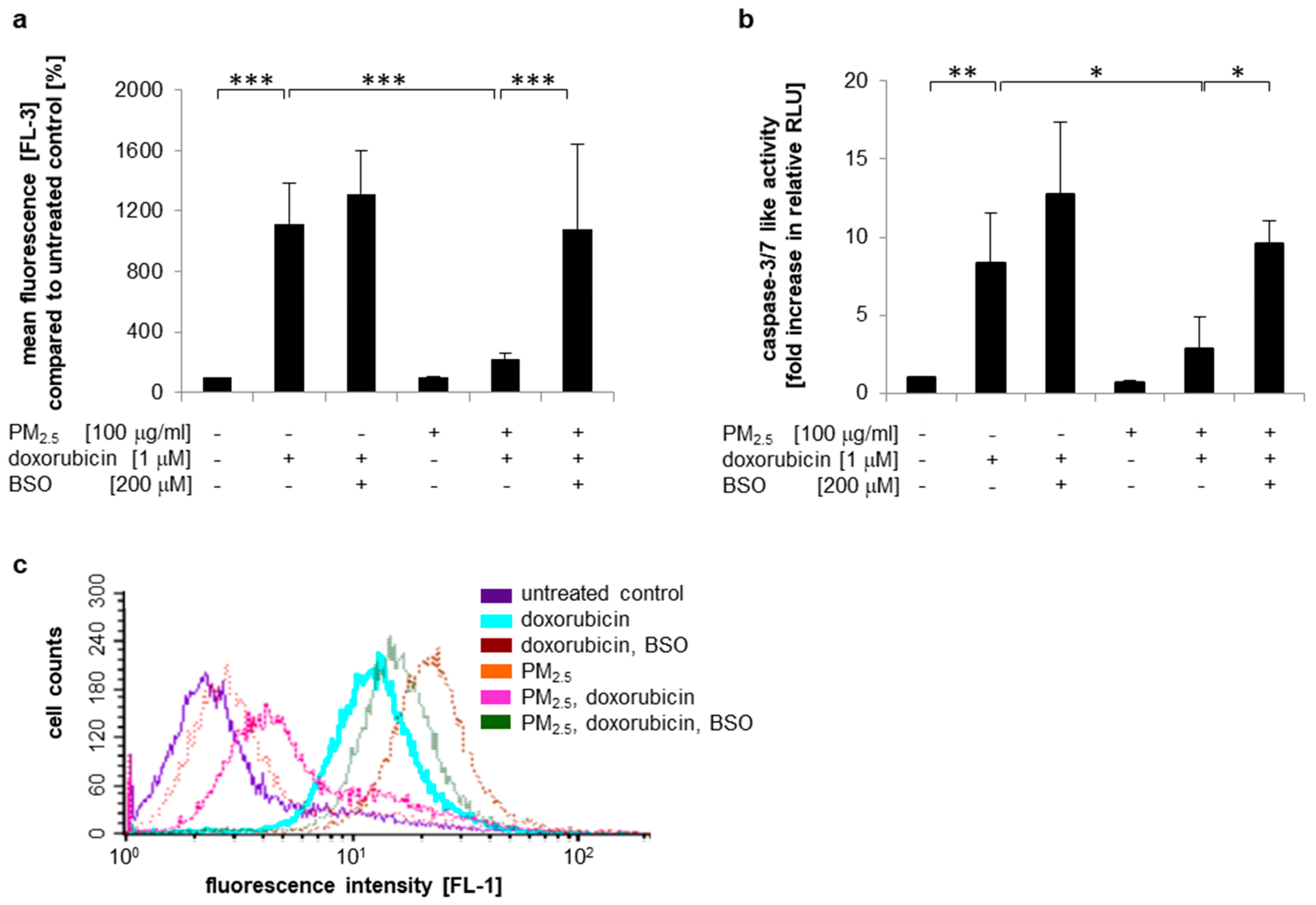

3.5. Impact of PM2.5 on Chemoresistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.N.; Balde, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I.; et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Health Topics: Fact Sheets. Cancer; WHO: Geneva, Swtizerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Health Topics: Questions & Answers. Indoor Air Pollution; WHO: Geneva, Swtizerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Health Topics: Fact sheets. Household Air Pollution and Health; WHO: Geneva, Swtizerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bentsen, N.S.; Felby, C. Biomass for energy in the European Union—A review of bioenergy resource assessments. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2012, 5, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Naeher, L.P.; Brauer, M.; Lipsett, M.; Zelikoff, J.T.; Simpson, C.D.; Koenig, J.Q.; Smith, K.R. Woodsmoke health effects: A review. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 67–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rumchev, K.; Zhao, Y.; Spickett, J. Health risk assessment of indoor air quality, socioeconomic and house characteristics on respiratory health among women and children of Tirupur, South India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 429. [Google Scholar]

- Valavanidis, A.; Fiotakis, K.; Vlachogianni, T. Airborne particulate matter and human health: Toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2008, 26, 339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Churg, A.; Brauer, M. Human lung parenchyma retains PM2.5. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 155, 2109–2111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Jahan, S.A.; Kabir, E. A review of diseases associated with household air pollution due to the use of biomass fuels. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muala, A.; Rankin, G.; Sehlstedt, M.; Unosson, J.; Bosson, J.A.; Behndig, A.; Pourazar, J.; Nystrom, R.; Pettersson, E.; Bergvall, C.; et al. Acute exposure to wood smoke from incomplete combustion--indications of cytotoxicity. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Happo, M.S.; Uski, O.; Jalava, P.I.; Kelz, J.; Brunner, T.; Hakulinen, P.; Maki-Paakkanen, J.; Kosma, V.M.; Jokiniemi, J.; Obernberger, I.; et al. Pulmonary inflammation and tissue damage in the mouse lung after exposure to PM samples from biomass heating appliances of old and modern technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 443, 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kocbach, A.; Herseth, J.I.; Lag, M.; Refsnes, M.; Schwarze, P.E. Particles from wood smoke and traffic induce differential pro-inflammatory response patterns in co-cultures. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 232, 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbach, K.; Kim, G.J.; Flemming, S.; Haupl, T.; Bonin, M.; Dornhof, R.; Gunther, S.; Merfort, I.; Humar, M. Disease relevant modifications of the methylome and transcriptome by particulate matter (PM2.5) from biomass combustion. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popadic, D.; Hesselbach, K.; Richter-Brockmann, S.; Kim, G.J.; Flemming, S.; Schmidt-Heck, W.; Haupl, T.; Bonin, M.; Dornhof, R.; Achten, C.; et al. Gene expression profiling of human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from biomass combustion. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 347, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dornhof, R.; Maschowski, C.; Osipova, A.; Giere, R.; Seidl, M.; Merfort, I.; Humar, M. Stress fibers, autophagy and necrosis by persistent exposure to PM2.5 from biomass combustion. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180291. [Google Scholar]

- Borlaza, L.J.S.; Cosep, E.M.R.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Joo, H.; Park, M.; Bate, D.; Cayetano, M.G.; Park, K. Oxidative potential of fine ambient particles in various environments. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Vattanasit, U.; Navasumrit, P.; Khadka, M.B.; Kanitwithayanun, J.; Promvijit, J.; Autrup, H.; Ruchirawat, M. Oxidative DNA damage and inflammatory responses in cultured human cells and in humans exposed to traffic-related particles. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, J.M.; Leonard, S.S.; Roberts, J.R.; Solano-Lopez, C.; Young, S.H.; Shi, X.; Taylor, M.D. Effect of stainless steel manual metal arc welding fume on free radical production, DNA damage, and apoptosis induction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2005, 279, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Nel, A.E. Role of the Nrf2-mediated signaling pathway as a negative regulator of inflammation: Implications for the impact of particulate pollutants on asthma. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, M.S.; de Oliveira Galvao, M.F.; Batistuzzo de Medeiros, S.R. Cell death pathways of particulate matter toxicity. Chemosphere 2017, 188, 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vomund, S.; Schafer, A.; Parnham, M.J.; Brune, B.; von Knethen, A. Nrf2, the Master regulator of anti-oxidative responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2772. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.Y.; Reddy, S.P.; Kleeberger, S.R. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, A.M.; Alam, J. Heme oxygenase-1: Function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1996, 15, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alam, J.; Stewart, D.; Touchard, C.; Boinapally, S.; Choi, A.M.; Cook, J.L. Nrf2, a Cap‘n’Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26071–26078. [Google Scholar]

- Hatem, E.; El Banna, N.; Huang, M.E. Multifaceted roles of glutathione and glutathione-based systems in carcinogenesis and anticancer drug resistance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 1217–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, R.; Cidlowski, J.A. Apoptosis and glutathione: Beyond an antioxidant. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 3143–3153. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Dan, H.C.; Park, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, Q.; Kaneko, S.; Ning, J.; He, L.; Yang, H.; Sun, M.; et al. AKT/PKB signaling mechanisms in cancer and chemoresistance. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azad, N.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Vallyathan, V. Inflammation and lung cancer: Roles of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2008, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.; Heerboth, S.; Lapinska, K.; Sarkar, S. Sensitization of drug resistant cancer cells: A matter of combination therapy. Cancers 2018, 10, 483. [Google Scholar]

- Na, H.K.; Surh, Y.J. Oncogenic potential of Nrf2 and its principal target protein heme oxygenase-1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 67, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, E.J.; Giaccia, A. Dual roles of NRF2 in tumor prevention and progression: Possible implications in cancer treatment. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 79, 292–299. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.; Kiang, A.; Lopez, J.P.; Kuo, S.Z.; Yu, M.A.; Abhold, E.L.; Chen, J.S.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Ongkeko, W.M. Cigarette smoke promotes drug resistance and expansion of cancer stem cell-like side population. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47919. [Google Scholar]

- Konczol, M.; Weiss, A.; Gminski, R.; Merfort, I.; Mersch-Sundermann, V. Oxidative stress and inflammatory response to printer toner particles in human epithelial A549 lung cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 216, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Strober, W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3.B.1–A3.B.3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, E.; Matthias, P.; Muller, M.M.; Schaffner, W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 6419. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Sternberg, P.; Cai, J. Essential roles of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway in regulating Nrf2-dependent antioxidant functions in the RPE. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, H.K.; Olayanju, A.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, B.K. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 705–717. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Talalay, P. NAD(P)H:quinone acceptor oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), a multifunctional antioxidant enzyme and exceptionally versatile cytoprotector. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 501, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.; Wakabayashi, N.; Misra, V.; Biswal, S.; Lee, G.H.; Agoston, E.S.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W. NRF2 modulates aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling: Influence on adipogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 7188–7197. [Google Scholar]

- Motlagh, N.S.; Parvin, P.; Ghasemi, F.; Atyabi, F. Fluorescence properties of several chemotherapy drugs: Doxorubicin, paclitaxel and bleomycin. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 2400–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Triller, N.; Korosec, P.; Kern, I.; Kosnik, M.; Debeljak, A. Multidrug resistance in small cell lung cancer: Expression of P-glycoprotein, multidrug resistance protein 1 and lung resistance protein in chemo-naive patients and in relapsed disease. Lung Cancer 2006, 54, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ryoo, I.G.; Kim, G.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kwak, M.K. Involvement of NRF2 Signaling in Doxorubicin Resistance of Cancer Stem Cell-Enriched Colonospheres. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 482–488. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Chu, S.; Bence, A.K.; Bailey, B.; Xue, X.; Erickson, P.A.; Montrose, M.H.; Beck, W.T.; Erickson, L.C. Quantitation of doxorubicin uptake, efflux, and modulation of multidrug resistance (MDR) in MDR human cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Szakacs, G.; Paterson, J.K.; Ludwig, J.A.; Booth-Genthe, C.; Gottesman, M.M. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Maitrejean, M.; Comte, G.; Barron, D.; El Kirat, K.; Conseil, G.; Di Pietro, A. The flavanolignan silybin and its hemisynthetic derivatives, a novel series of potential modulators of P-glycoprotein. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani, H.; Tada-Oikawa, S.; Hiraku, Y.; Kojima, M.; Kawanishi, S. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by doxorubicin through the generation of hydrogen peroxide. Life Sci. 2005, 76, 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suresh, A.; Guedez, L.; Moreb, J.; Zucali, J. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase promotes survival in cell lines after doxorubicin treatment. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 120, 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- Gouaze, V.; Mirault, M.E.; Carpentier, S.; Salvayre, R.; Levade, T.; Andrieu-Abadie, N. Glutathione peroxidase-1 overexpression prevents ceramide production and partially inhibits apoptosis in doxorubicin-treated human breast carcinoma cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 488–496. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, C.; Muhlbauer, J.; Perlmutter, G.; Taparra, K.; Phelan, S.A. Peroxiredoxin proteins protect MCF-7 breast cancer cells from doxorubicin-induced toxicity. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Thompson, M.A.; Tamayo, A.T.; Zuo, Z.; Lee, J.; Vega, F.; Ford, R.J.; Pham, L.V. Over-expression of Thioredoxin-1 mediates growth, survival, and chemoresistance and is a druggable target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffith, O.W. Mechanism of action, metabolism, and toxicity of buthionine sulfoximine and its higher homologs, potent inhibitors of glutathione synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 13704–13712. [Google Scholar]

- Bentayeb, M.; Simoni, M.; Baiz, N.; Norback, D.; Baldacci, S.; Maio, S.; Viegi, G.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Geriatric study in Europe on Health Effects of Air Quality in Nursing Homes Group. Adverse respiratory effects of outdoor air pollution in the elderly. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2012, 16, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.J.; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Environmental Health. Ambient air pollution: Health hazards to children. Pediatrics 2004, 114, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Davies, K.J.A.; Forman, H.J. Oxidative stress response and Nrf2 signaling in aging. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sehgal, A.; Saili, A.; Gupta, R.P.; Bajaj, P. Free oxygen radicals and immune profile in newborns with lung diseases. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2000, 46, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Han, I.K.; Hu, M.; Shao, M.; Zhang, J.J.; Tang, X. Personal exposure to particulate PAHs and anthraquinone and oxidative DNA damages in humans. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, V.; Valverde, M.; Rojas, E. Effects of atmospheric pollutants on the Nrf2 survival pathway. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2010, 17, 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 4350965. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Rui, W.; Zhang, F.; Ding, W. PM2.5 induces Nrf2-mediated defense mechanisms against oxidative stress by activating PIK3/AKT signaling pathway in human lung alveolar epithelial A549 cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2013, 29, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Xia, Y.; Niu, P.; Jiang, L.; Duan, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z. Silica nanoparticles induce oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction in vitro via activation of the MAPK/Nrf2 pathway and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 1463–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaraman, B.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Davies, K.J.; Dennery, P.A.; Forman, H.J.; Grisham, M.B.; Mann, G.E.; Moore, K.; Roberts, L.J., 2nd; Ischiropoulos, H. Measuring reactive oxygen and nitrogen species with fluorescent probes: Challenges and limitations. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Kovochich, M.; Nel, A.E. Impairment of mitochondrial function by particulate matter (PM) and their toxic components: Implications for PM-induced cardiovascular and lung disease. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshi, H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Matsuyama, K.; Nakazato, Y.; Tochigi, S.; Kondoh, S.; Hirai, T.; Akase, T.; Nagano, K.; Abe, Y.; et al. Amorphous nanosilica induce endocytosis- dependent ROS generation and DNA Damage in human keratinocytes. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2011, 8, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Margaritis, M.; Channon, K.M.; Antoniades, C. Evaluating oxidative stress in human cardiovascular disease: Methodological aspects and considerations. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 2504–2520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Weis, S.; Yang, G.; Weng, Y.H.; Helston, R.; Rish, K.; Smith, A.; Bordner, J.; Polte, T.; Gaunitz, F.; et al. Heme oxygenase-1 protein localizes to the nucleus and activates transcription factors important in oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20621–20633. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, C.; Shah, N.; Muthu, M.; La, P.; Fernando, A.P.; Sengupta, S.; Yang, G.; Dennery, P.A. Nuclear heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) modulates subcellular distribution and activation of Nrf2, impacting metabolic and anti-oxidant defenses. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 26882–26894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghio, A.J. Particle exposures and infections. Infection 2014, 42, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ciencewicki, J.; Jaspers, I. Air pollution and respiratory viral infection. Inhal. Toxicol. 2007, 19, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, W.T.; Liu, H.J. PI3K-Akt signaling and viral infection. Recent Pat. Biotechnol. 2008, 2, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, C.; Ludwig, S. A new player in a deadly game: Influenza viruses and the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 863–871. [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh, M.U.; Manzanillo, P.; Cox, J.S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis senses host-derived carbon monoxide during macrophage infection. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Okoh, V.O.; Felty, Q.; Parkash, J.; Poppiti, R.; Roy, D. Reactive oxygen species via redox signaling to PI3K/AKT pathway contribute to the malignant growth of 4-hydroxy estradiol-transformed mammary epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54206. [Google Scholar]

- Kurie, J.M. Role of protein kinase B-dependent signaling in lung tumorigenesis. Chest 2004, 125 (Suppl. 5), 141S–144S. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.; Ouyang, G.; Bai, X.; Huang, Z.; Ma, C.; Liu, M.; Shao, R.; Anderson, R.M.; Rich, J.N.; Wang, X.F. Periostin potently promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer by augmenting cell survival via the Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer Cell 2004, 5, 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, L.Y. Heme oxygenase-1: Emerging target of cancer therapy. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 22, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Tibullo, D.; Barbagallo, I.; Giallongo, C.; Vanella, L.; Conticello, C.; Romano, A.; Saccone, S.; Godos, J.; Di Raimondo, F.; Li Volti, G. Heme oxygenase-1 nuclear translocation regulates bortezomibinduced cytotoxicity and mediates genomic instability in myeloma cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28868–28880. [Google Scholar]

- Polewski, M.D.; Reveron-Thornton, R.F.; Cherryholmes, G.A.; Marinov, G.K.; Aboody, K.S. SLC7A11 Overexpression in glioblastoma is associated with increased cancer stem cell-like properties. Stem Cells Dev. 2017, 26, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.H.; Hur, E.G.; Kang, S.J.; Kim, J.A.; Thapa, D.; Lee, Y.M.; Ku, S.K.; Jung, Y.; Kwak, M.K. NRF2 blockade suppresses colon tumor angiogenesis by inhibiting hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1alpha. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2260–2275. [Google Scholar]

- Santibáñez-Andrade, M.; Chirino, Y.I.; González-Ramírez, I.; Sánchez-Pérez, Y.; García-Cuellar, C.M. Deciphering the code between air pollution and disease: The effect of particulate matter on cancer hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, S.P.; Cockburn, M.; Shu, Y.H.; Deng, H.; Lurmann, F.W.; Liu, L.; Gilliland, F.D. Air pollution affects lung cancer survival. Thorax 2016, 71, 891–898. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, J.Y.; Hanson, H.A.; Ramsay, J.M.; Leiser, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; Vanderslice, J.A.; Pope, C.A.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Fine particulate matter and respiratory healthcare encounters among survivors of childhood cancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1081. [Google Scholar]

- Dzobo, K.; Hassen, N.; Senthebane, D.A.; Thomford, N.E.; Rowe, A.; Shipanga, H.; Wonkam, A.; Parker, M.I.; Mowla, S.; Dandara, C. Chemoresistance to cancer treatment: Benzo-a-Pyrene as friend or foe? Molecules 2018, 23, 930. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, B.K.; Katki, A.G.; Batist, G.; Cowan, K.H.; Myers, C.E. Adriamycin-stimulated hydroxyl radical formation in human breast tumor cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1987, 36, 793–796. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Letai, A.; Sarosiek, K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: The balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, A.B.; Freel, C.D.; Kornbluth, S. Cellular mechanisms controlling caspase activation and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008672. [Google Scholar]

- Efferth, T.; Volm, M. Multiple resistance to carcinogens and xenobiotics: P-glycoproteins as universal detoxifiers. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2515–2538. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, F.Y.; Vessey, A.R.; Siemann, D.W. Glutathione as a determinant of cellular response to doxorubicin. NCI Monogr. 1988, 6, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, T.C.; Winker, M.A.; Louie, K.G.; Batist, G.; Behrens, B.C.; Tsuruo, T.; Grotzinger, K.R.; McKoy, W.M.; Young, R.C.; Ozols, R.F. Augmentation of adriamycin, melphalan, and cisplatin cytotoxicity in drug-resistant and -sensitive human ovarian carcinoma cell lines by buthionine sulfoximine mediated glutathione depletion. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34, 2583–2586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahman, Q.; Abidi, P.; Afaq, F.; Schiffmann, D.; Mossman, B.T.; Kamp, D.W.; Athar, M. Glutathione redox system in oxidative lung injury. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1999, 29, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wellner, V.P.; Anderson, M.E.; Puri, R.N.; Jensen, G.L.; Meister, A. Radioprotection by glutathione ester: Transport of glutathione ester into human lymphoid cells and fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4732–4735. [Google Scholar]

- Vinette, V.; Placet, M.; Arguin, G.; Gendron, F.P. Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 expression is upregulated by adenosine 5’-triphosphate in colorectal cancer cells and enhances their survival to chemotherapeutic drugs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136080. [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers, M.H. ATP-binding-cassette transporters in hematopoietic stem cells and their utility as therapeutical targets in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2007, 21, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath, V.; Wielandt, A.M.; Iruretagoyena, M.; Chianale, J. Role of Nrf2 in the regulation of the Mrp2 (ABCC2) gene. Biochem. J. 2006, 395, 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- AbuHammad, S.; Zihlif, M. Gene expression alterations in doxorubicin resistant MCF7 breast cancer cell line. Genomics 2013, 101, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Volkova, M.; Palmeri, M.; Russell, K.S.; Russell, R.R. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by doxorubicin mediates cytoprotective effects in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 90, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.C. The molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 59950–59964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Zheng, Y.S.; Zhang, X.J.; Han, B.W.; Luo, X.Q.; Xu, L.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L.H.; et al. Down-regulated miR-331-5p and miR-27a are associated with chemotherapy resistance and relapse in leukaemia. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Xia, F.; Ma, L.; Shan, J.; Shen, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y.; Bian, X.; Bie, P.; et al. MicroRNA-122 sensitizes HCC cancer cells to adriamycin and vincristine through modulating expression of MDR and inducing cell cycle arrest. Cancer Lett. 2011, 310, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D.; Fu, A.; Zhang, E. MicroRNA-126 increases chemosensitivity in drug-resistant gastric cancer cells by targeting EZH2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xiao, F.; Guo, Y. Gene expression profiling of drug-resistant small cell lung cancer cells by combining microRNA and cDNA expression analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1692–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Dai, Y.; Wang, S.; Xing, X. MicroRNA-299-3p promotes the sensibility of lung cancer to doxorubicin through directly targeting ABCE1. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 10072–10081. [Google Scholar]

| Gene Symbol | Encoded Protein | p-Value | log2FC | FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKR1C1‡ | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C1 | 0.0043 | 1.53 | 2.89 |

| AKR1C2‡ | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C2 | 0.0038 | 1.66 | 3.16 |

| AKR1C3‡ | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 | 0.0066 | 1.25 | 2.38 |

| CYP1A1§ | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 0.0011 | 2.54 | 5.82 |

| EGR1† | early growth response 1 | 0.0080 | 1.01 | 2.02 |

| EREG‡ | Epiregulin | 0.0008 | 2.73 | 6.65 |

| FAM83B‡ | family with sequence similarity 83, member B | 0.0058 | 1.26 | 2.40 |

| GCLC§ | glutamate-cysteine ligase, catalytic subunit | 0.0197 | 0.80 | 1.74 |

| GOS2‡ | switch protein 2 | 0.0017 | 1.25 | 2.37 |

| GREM1‡ | gremlin 1, DNA family BMP antagonist | 0.0017 | 2.85 | 7.20 |

| HMOX1†,‡ | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 0.0035 | 1.23 | 2.34 |

| IL1A‡ | interleukin 1, alpha | 0.0014 | 2.32 | 5.00 |

| ITGA2‡ | integrin, alpha 2 | 0.0011 | 1.54 | 2.90 |

| NQO1§ | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | 0.0482 | 0.71 | 1.64 |

| S100A9‡ | S100 calcium binding protein A9 | 0.0052 | 2.05 | 4.15 |

| SLC7A11† | solute carrier family 7 (anionic amino acid transporter light chain, xc-system), member 11; xCT | 0.0072 | 1.69 | 3.24 |

| SPOCK1‡ | sparc/osteonectin | 0.0080 | 1.04 | 2.05 |

| STEAP1‡ | six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate1 | 0.0059 | 1.34 | 2.53 |

| STC2‡ | stanniocalcin 2 | 0.0090 | 0.79 | 1.73 |

| TPBG‡ | trophoblast glycoprotein | 0.0038 | 0.93 | 1.91 |

| TGFA†,‡ | transforming growth factor, alpha | 0.0038 | 2.04 | 4.10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merk, R.; Heßelbach, K.; Osipova, A.; Popadić, D.; Schmidt-Heck, W.; Kim, G.-J.; Günther, S.; Piñeres, A.G.; Merfort, I.; Humar, M. Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218193

Merk R, Heßelbach K, Osipova A, Popadić D, Schmidt-Heck W, Kim G-J, Günther S, Piñeres AG, Merfort I, Humar M. Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218193

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerk, Regina, Katharina Heßelbach, Anastasiya Osipova, Désirée Popadić, Wolfgang Schmidt-Heck, Gwang-Jin Kim, Stefan Günther, Alfonso García Piñeres, Irmgard Merfort, and Matjaz Humar. 2020. "Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 8193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218193

APA StyleMerk, R., Heßelbach, K., Osipova, A., Popadić, D., Schmidt-Heck, W., Kim, G.-J., Günther, S., Piñeres, A. G., Merfort, I., & Humar, M. (2020). Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Biomass Combustion Induces an Anti-Oxidative Response and Cancer Drug Resistance in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218193