Occupational Stress and Its Economic Cost in Hong Kong: The Role of Positive Emotions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Global Economic Impact of Occupational Stress

2.2. The Cost of Absenteeism

2.3. The Cost of Presenteeism

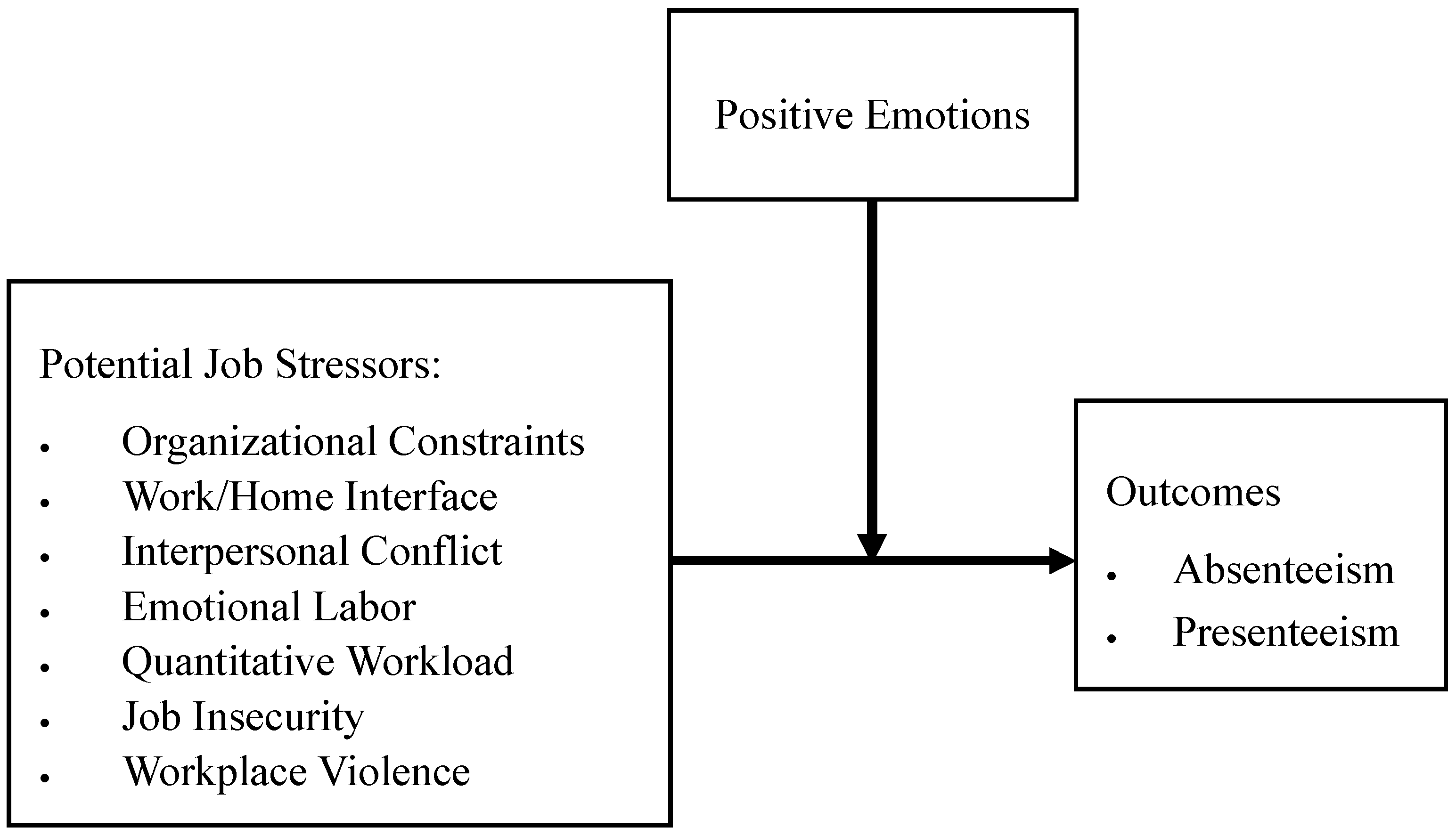

2.4. The Role of Positive Emotions

2.5. The Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.1.1. Focus Group Discussions

3.1.2. The Survey

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis for Focus Group Discussions

3.4. Data Analysis for the Survey

4. Results

4.1. Focus Group Discussions

4.1.1. Social and Personal Services (Education)

“I am the class teacher who teaches English. I felt stressed about students’ academic results (related to secondary school place allocation).”

“I have a serious SEN student in class. He/she shouts in class during lessons. I have to take care of the discipline and keep the teaching on schedule.”

4.1.2. Social and Personal Services (Health and Social Work Services)

“I generally (have to work) six continuous days, sometimes up to nine.”

“Clients sometimes kick you or scratch you.”

4.1.3. Financial and Insurance Industry

“The tasks are given very late.”

“I feel stressed when comparing myself with others. Others are doing faster than me.”

4.1.4. Information and Communication Industry

“The update in software and hardware is too quick. [I] have a feeling of being eliminated/excluded.”

“The supervisor gave complicated tasks, but the time is insufficient.”

4.2. The Survey

4.2.1. Testing Normal Distributions of Variables

4.2.2. Factor Structure of Job Stressors

4.3. Calculating the Cost of Absenteeism

- (a)

- Calculating the average number of absences in days per month (from the WHO scale), equal to M (average number of absenteeism hours in four weeks; the value is 4.72, which is captured in Table 4)/M (work hours that your employer expects you to work in a typical week/7; the value captured from the WHO scale is 48/7), namely, 4.72/(48/7) = 0.69 day;

- (b)

- Estimating the variance of absenteeism attributable to the five job stressors. The value was captured in the hierarchical regression results depicted in Table 3. In this study, the figure was 3%;

- (c)

- The cost attributable to absenteeism each day could be roughly estimated by the employees’ average daily salary. In this study, the median monthly salary was HK$16,000 to HK$24,999 (4 weeks) or HK$571.43 to HK$892.82 in terms of the daily salary.

4.4. Calculating the Cost of Presenteeism

- (a)

- Calculating the average number of days of presenteeism per month. Because such data are difficult to measure, we adopted the recommendation of the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. The UK report showed that the estimated ratio of presenteeism to absenteeism was 1.5. [83], p. 1. The number in our study was 1.035 days (0.69 × 1.5);

- (b)

- Estimating the variance of presenteeism attributable to the five job stressors. The value was captured through hierarchical regression, as seen in Table 3. In this study, the figure was 5%;

- (c)

- The cost attributable to presenteeism each day could be roughly estimated by the employees’ average daily salary. In this study, the median monthly salary was HK$16,000 to HK$24,999 (4 weeks) or HK$571.43 to HK$892.82 in terms of the daily salary.

4.5. Calculating the Cost of Medical Treatment (Medical Expenses)

- (a)

- Calculating the average number of times an employee sees a doctor in one year (the value was captured from the WHO scale). In our sample, the number was six.

- (b)

- Estimating the basic cost of treatment at public clinics. The government provides public healthcare to all residents of Hong Kong, including non-permanent residents. Hong Kong has a comprehensive public healthcare system, including hospitals, clinics, and specialist care. The fees for visiting an Accident & Emergency (A & E) department under the Hospital Authority (HA) are regulated by the government and are very moderate, especially when compared to the prices of private clinics. Effective from 18 June 2017, in general, eligible persons (e.g., people with a Hong Kong ID) pay HK$180 for one visit to an A & E. Therefore, we adopted HK$180 as the basic cost for one visit to a public clinic (note that the cost for private clinics is much higher). Because the government may sponsor the HA’s expenses, to capture more realistic expenses, we also considered the fees for a non-eligible person, which are HK$1230 per visit [85].

- (c)

- The cost attributable to sickness absence each day could be roughly estimated by the employees’ average daily salary. In this study, the median monthly salary was HK$16,000 to HK$24,999 (4 weeks) or HK$571.43 to HK$892.82 in terms of the daily salary;

- (d)

- Calculating the average number of sickness absence days in one year. In our sample, the number was 3.2. Please note that the 1995 data were credible enough to estimate the sickness absence after checking;

- (e)

- The cost of sickness absence equaled (c) × (d). In our sample, the figure would be HK$1828.58 to HK$2,857.02, which represents the annual cost per employee due to sickness absence.

Total Economic Cost of Stress

5. Discussion

5.1. Methodological and Theoretical Contributions of the Study

5.2. Practical Implications for Occupational Health Psychology

5.3. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassard, J.; Teoh, K.R.H.; Visockaite, G.; Dewe, P.; Cox, T. The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakata, M. Trends in research and prevention policies for work-related musculoskeletal disorders at the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2002, 44, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Michie, S. Causes and Management of Stress at Work. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 59, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spurgeon, A.; Harrington, J.M.; Cooper, C.L. Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: A review of the current position. Occup. Environ. Med. 1997, 54, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahtera, J.; Pentti, J.; Kivimäki, M. Sickness absence as a predictor of mortality among male and female employees. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johns, G. Presenteeism in the workplace: A review and research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. Attendance dynamics at work: The antecedents and correlates of presenteeism, absenteeism, and productivity loss. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stambor, Z.; American Psychological Association; Public Information and Media Relations. Public Communications Employees: A company’s best asset. PsycEXTRA Dataset 2013, 37, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Work Australia. The Cost of Work-Related Injury and Illness for Australian Employers, Workers and the Community: 2008–09; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2012.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Calculating the Cost of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks—European Risk Observatory: A literature Review; Publications Office of European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/tools-and-publications/publications/literature_reviews/calculating-the-cost-of-work-related-stress-and-psychosocial-risks (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- European Commission. Guidance on Work-Related Stress: Spice of Life or Kiss of Death; European Communities: Luxembourg, 2002; Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/data/links/guidance-on-work-related-stress (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- McTernan, W.P.; Dollard, M.F.; Lamontagne, A.D. Depression in the workplace: An economic cost analysis of depression-related productivity loss attributable to job strain and bullying. Work. Stress 2013, 27, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—A meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlaine, A.; Leger, D.; Choudat, D. Socioeconomic Impact of Insomnia in Working Populations. Ind. Health 2005, 43, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lang, J.; Ochsmann, E.B.; Kraus, T.; Lang, J.W.B. Psychosocial work stressors as antecedents of musculoskeletal problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of stability-adjusted longitudinal studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofland, J.H.; Pizzi, L.; Frick, K.D. A Review of Health-Related Workplace Productivity Loss Instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 2004, 22, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSE—Health and Safety Executive. Costs to Britain of Workplace Fatalities and Self-Reported Injuries and Ill Health, 2010/11 (Data Complemented through Direct Correspondence with the HSE). 2013. Available online: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/index.htm (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Bourbonnais, R.; Mondor, M. Job strain and sickness absence among nurses in the province of Quebec. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2001, 39, 194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, B. Occupational stress factors–Survey among employees of intercompany services. Les facteurs de stress professionnel–Enquête auprès des salariés des services interentreprises. Arch. Mal. Prof. Méd. Trav. 2003, 64, 297–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti, J.; Kivimaki, M.; Pentti, J.; Suominen, S.; Vahtera, J.; Virtanen, M. Sickness absence among Finnish special and general education teachers. Occup. Med. 2011, 61, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmgren, K.; Fjällström-Lundgren, M.; Hensing, G. Early identification of work-related stress predicted sickness absence in employed women with musculoskeletal or mental disorders: A prospective, longitudinal study in a primary health care setting. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 35, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hirokawa, K.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kobayashi, F.; Haratani, T.; Araki, S.; Kawakami, N. Job strain and sick leave among Japanese employees: A longitudinal study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2005, 79, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Garbarino, S. Is Absence Related to Work Stress? A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study on a Special Police Force. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, J.P.; Lamarche, C. Assessing the Costs of Work Stress; Université Laval: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hout, W.V.D. The value of productivity: Human-capital versus friction-cost method. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 69, i89–i91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelin, E.H. Work disability in rheumatic diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2007, 19, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmanschap, M.A.; Rutten, F.F.; Van Ineveld, B.; Van Roijen, L. The friction cost method for measuring indirect costs of disease. J. Health Econ. 1995, 14, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, H. Friction-Cost Method as an Alternative to the Human-Capital Approach in Calculating Indirect Costs. Pharmacoeconomics 2005, 23, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Dewe, P. Well-being--absenteeism, presenteeism, costs and challenges. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronsson, G.; Gustafsson, K.; Dallner, M. Sick but yet at work. An empirical study of sickness presenteeism. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2000, 54, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dew, K.; Keefe, V.; Small, K. ‘Choosing’ to work when sick: Workplace presenteeism. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L. Presenteeism Is More Costly than Absenteeism. HR Magazine. 2011. Available online: http://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/hro/features/101955/presenteeism-costly-absenteeism (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Hemp, P. Presenteeism: At work—But out of it. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia, M.; Johns, G. Going to work ill: A meta-analysis of the correlates of presenteeism and a dual-path model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aronsson, G.; Gustafsson, K. Sickness Presenteeism: Prevalence, Attendance-Pressure Factors, and an Outline of a Model for Research. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 47, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C.D.; Andersen, J.H. Going ill to work – What personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elstad, J.I.; Vabø, M. Job stress, sickness absence and sickness presenteeism in Nordic elderly care. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.J.; Baase, C.M.; Sharda, C.E.; Ozminkowski, R.J.; Nicholson, S.; Billotti, G.M.; Turpin, R.S.; Olson, M.; Berger, M.L. The Assessment of Chronic Health Conditions on Work Performance, Absence, and Total Economic Impact for Employers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005, 47, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaid, D. The economics of mental health in the workplace: What do we know and where do we go? Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2007, 16, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klein, J. Presenteeism, Absenteeism and psychosocial stress at work among German clinicians in surgery. Gesundh. Bundesverb. Arzte Offentlichen Gesundh. Ger. 2013, 75, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Krol, M.; Brouwer, W.B.F.; Severens, J.L.; Kaper, J.B.; Evers, S.M. Productivity cost calculations in health economic evaluations: Correcting for compensation mechanisms and multiplier effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangri, R. What Stress Costs; Chrystalis Performance Strategies Inc.: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Ames, M.; Hymel, P.A.; Loeppke, R.; McKenas, D.K.; Richling, D.; Stang, P.E.; Üstün, T.B. Using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, S23–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. Handb. Posit. Psychol. 2002, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pressman, S.D.; Cohen, S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J.; Marmot, M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 6508–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schutte, N.S. The broaden and build process: Positive affect, ratio of positive to negative affect and general self-efficacy. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 9, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, G.; Bodin, L.; Hagberg, J.; Aronsson, G.; Josephson, M. Sickness Presenteeism Today, Sickness Absenteeism Tomorrow? A Prospective Study on Sickness Presenteeism and Future Sickness Absenteeism. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, W.N.; Pransky, G.; Conti, D.J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Edington, D.W. The Association of Medical Conditions and Presenteeism. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 46, S38–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darr, W.; Johns, G. Work strain, health, and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, A.B.; Chen, C.-Y.; Edington, D.W.; Edington, D.W. The Cost and Impact of Health Conditions on Presenteeism to Employers. Pharmacoeconomics 2009, 27, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.; Stoner, J.; Hochwarter, W.; Kacmar, C. Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.-L.; Cheung, F.Y.L.; Lui, S. Linking Positive Emotions to Work Well-Being and Turnover Intention Among Hong Kong Police Officers: The Role of Psychological Capital. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Barrett, L.F. Psychological Resilience and Positive Emotional Granularity: Examining the Benefits of Positive Emotions on Coping and Health. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 1161–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Antecedents of day-level proactive behaviour: A look at job stressors and positive affect during the workday. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Spector, P.E.; Shi, L. Cross-national job stress: A quantitative and qualitative study. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occupational Safety & Health Council (OSHC). Work Stress Management DIY Kit, 2nd ed.; OSHC: Hong Kong, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, O.-L.; Lu, C.-Q.; Spector, P.E. Direct and indirect relationship between social stressors and job performance in Greater China: The role of strain and social support. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.-L.; Lu, C.-Q.; Spector, P.E. Employees? Well-being in Greater China: The Direct and Moderating Effects of General Self-efficacy. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, C.-Q.; Siu, O.-L. Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census and Statistics Department. 2018 Report on Annual Earnings and Hours Survey. 2018. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10500142018AN18B0100.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Keenan, A.; Newton, T.J. Stressful events, stressors and psychological strains in young professional engineers. J. Organ. Behav. 1985, 6, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organisational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, UK). Public Health Guidance 22: Promoting Metal Wellbeing at Work. Costing Tool for Employers. Implementing NICE Guidance. 2009. Available online: https://www.the-stress-site.net/uploads/2/7/0/6/2706840/_ph22_promoting_mental_wellbeing_business_case_tool.xls (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Lu, L.; Kao, S.-F.; Siu, O.-L.; Lu, C.-Q. Work stressors, Chinese coping strategies, and job performance in Greater China. Int. J. Psychol. 2010, 45, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Nauta, M.M.; Spector, P.E.; Li, C. Direct and indirect conflicts at work in China and the US: A cross-cultural comparison. Work. Stress 2008, 22, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-F.; Siu, O.-L.; Spector, P.E.; Shi, K. Antecedents and outcomes of a fourfold taxonomy of work-family balance in Chinese employed parents. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siu, O.-L.; Chow, S.L.; Phillips, D.R.; Lin, L. An Exploratory Study of Resilience among Hong Kong Employees: Ways to Happiness. In Happiness and Public Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barber, C.; Beck, A.L.; Berglund, P.A.; Cleary, P.D.; McKenas, D.; Pronk, N.P.; Simon, G.E.; Stang, P.E.; Üstün, T.B.; et al. The World Health Organisation Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, O.-L.; Spector, P.E.; Cooper, C.L. A three-phase study to develop and validate a Chinese coping strategies scales in Greater China. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Mills, M.J.; Fan, J. Job stressors, job performance, job dedication, and the moderating effect of conscientiousness: A mixed-method approach. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2013, 20, 336–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén Linda, K.; Muthén Bengt, O. Mplus User’s Guide; Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky, J.; Jager, J.; Hemken, D. Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, R.H.; Myers, R.H. Classical and Modern Regression with Applications; Duxbury Press: Belmont, CA, USA, 1990; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. Quarterly Report on General Household Survey, October to December 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10500012018QQ04B0100.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. Mental Health at Work: Developing a Business Case, Policy Paper; Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Trontin, C.; Lassagne, M.; Boini, S.; Rinal, S. Le Coût du Stress Professionnel en France en 2007; Institut National de Recherche et de Sécurité (INRS): Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hospital Authority. Fees and Charges. 2017. Available online: http://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/fees_and_charges.asp?lang=ENG#b (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Hoel, H.; Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.L. The Cost of Violence/Stress at Work and the Benefits of a Violence/Stress-Free Working Environment; International Labour Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Census and Statistics Department. 2018 Gross Domestic Product. 2019. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10300022018AN18E0100.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Bödeker, W.; Friedrichs, M. Kosten der psychischen Erkrankungen und Belastungen in Deutschland. In Regelungslücke Psychische Belastungen Schliessen; Kamp, L., Pickshaus, K., Eds.; Hans Bockler Stiftung: Dusseldorf, Germany, 2011; pp. 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Van Wijhe, C.I. Good morning, good day: A diary study on positive emotions, hope, and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prev. Treat. 2000, 3, 1a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Cohn, M.A.; Coffey, K.A.; Pek, J.; Finkel, S.M. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruhle, S.A.; Süß, S. Presenteeism and Absenteeism at Work—An Analysis of Archetypes of Sickness Attendance Cultures. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 35, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable. | Category | N | Percentage | No. and Percentage of Persons Engaged (Dec. 2017) (Except Public Administration) 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industries | Construction | 205 | 10.1 | 122,761 2 (4.3%) |

| Education | 331 | 16.3 | 201,488 (7.1%) | |

| Human health and social work service | 280 | 13.8 | 158,606 (5.5%) | |

| Financing and insurance | 336 | 16.5 | 227,156 (7.9%) | |

| Public administration (including government administration, economic and social policy, public order, and safety activities) | 150 | 7.4 | 111,009 (2.9%) 3 | |

| Accommodation and food services | 124 | 6.1 | 283,505 (9.9%) | |

| Transportation | 200 | 9.8 | 85,191 (3.0%) | |

| Import/export, wholesale, and retail trades | 149 | 7.3 | 807,499 (28.3%) | |

| Information and communications | 18 | 0.9 | 107,122 (3.7%) | |

| Real estate | 46 | 2.3 | 131,855 (4.6%) | |

| Social and personal services (other services) | 37 | 1.8 | 76,866 (2.7%) | |

| Professional and business services (Professional, scientific, and technical services and administrative and support services) | 44 | 2.2 | 377,659 (13.2%) | |

| Others (like manufacturing, sports, supply, arts, NGO, etc.) | 40 | 2.0 | ||

| Missing | 72 | 3.5 |

| . | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work/Home Interface | 2.53 | 1.25 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Job Insecurity | 1.89 | 1.00 | 0.48 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Interpersonal Conflict | 2.13 | 1.09 | 0.53 *** | 0.44 *** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Quantitative Workload | 2.68 | 1.25 | 0.66 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.54 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Organizational Constraints | 2.44 | 1.13 | 0.59 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.66 *** | 1 | |||

| 6. Positive Emotions | 3.50 | 0.97 | −0.29 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.24 *** | −0.33 *** | 1 | ||

| 7. Absenteeism | 4.72 | 46.74 | −0.02 | 0.08 *** | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 1 | |

| 8. Presenteeism | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.14 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.18 *** | -0.23 *** | 0.04 | 1 |

| Predictor. | Absenteeism | Presenteeism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Age | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.09 ** |

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Marital Status | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Education Level | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 * | −0.04 |

| Tenure | 0.06 | 0.08 * | −0.10 *** | −0.07 * |

| Position | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 * | −0.04 |

| Organization Type | −0.09 ** | −0.07 * | −0.02 | −0.01 |

| Lifestyle | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 * | −0.03 |

| Industry | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ΔR2 | 0.02 * | 0.04 *** | ||

| Work/Home Interface | −0.13 ** | 0.01 | ||

| Job Insecurity | 0.13 *** | 0.16 *** | ||

| Interpersonal Conflict | 0.02 | 0.06 * | ||

| Quantitative Workload | −0.10 * | −0.08 * | ||

| Organizational Constraints | 0.08 | 0.09 * | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 *** | 0.05 *** | ||

| Source. | Formula | a | b | c | d | HK Population of Employees (Million) | Total (Million HKD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absenteeism | (a) × (b) × (c) × 12 × HK population | 0.69 | 3% | 571.43–892.82 | N/A | 3.87 | 549.32–858.28 |

| census data | 625 | 600.82 | |||||

| Presenteeism | (a) × (b) × (c) × 12 × HK population | 1.035 | 5% | 571.43–892.82 | N/A | 3.87 | 1373.30–2145.69 |

| census data | 625 | 1502.04 | |||||

| Medial Cost | {(a) × (b) + (c) × (d)} × 30% × HK population | 6 | 180–1230 | 571.43–892.82 | 3.2 | 3.87 | 3376.85−11,885.19 |

| census data | 625 | 3575.88−10,890.18 | |||||

| Total | Based on sample data | 5299.47–14,889.16 | |||||

| Based on census data | 5678.74–12,993.04 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siu, O.L.; Cooper, C.L.; Roll, L.C.; Lo, C. Occupational Stress and Its Economic Cost in Hong Kong: The Role of Positive Emotions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228601

Siu OL, Cooper CL, Roll LC, Lo C. Occupational Stress and Its Economic Cost in Hong Kong: The Role of Positive Emotions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(22):8601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228601

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiu, Oi Ling, Cary L. Cooper, Lara C. Roll, and Carol Lo. 2020. "Occupational Stress and Its Economic Cost in Hong Kong: The Role of Positive Emotions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 22: 8601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228601

APA StyleSiu, O. L., Cooper, C. L., Roll, L. C., & Lo, C. (2020). Occupational Stress and Its Economic Cost in Hong Kong: The Role of Positive Emotions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228601