Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in the Decision-Making of Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: The Case of Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Existing Research in Decision-Making and Stakeholder Participation in ILR in China

2.1. Decision-Making of ILR

2.2. Stakeholder Participation in ILR Decision-Making in China

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

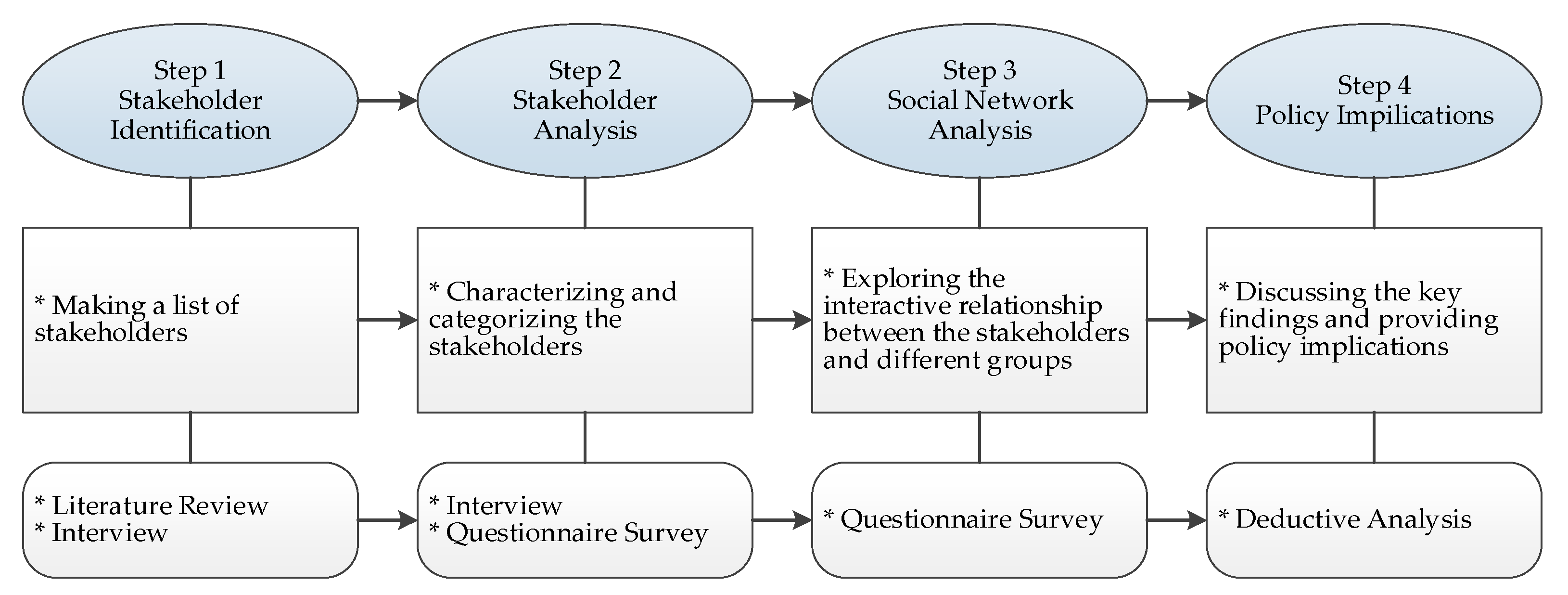

3.2. Combination of SA and SNA

3.3. Semi-Structured Interview

3.4. Questionnaire Survey

4. Results

4.1. Identification of Stakeholders

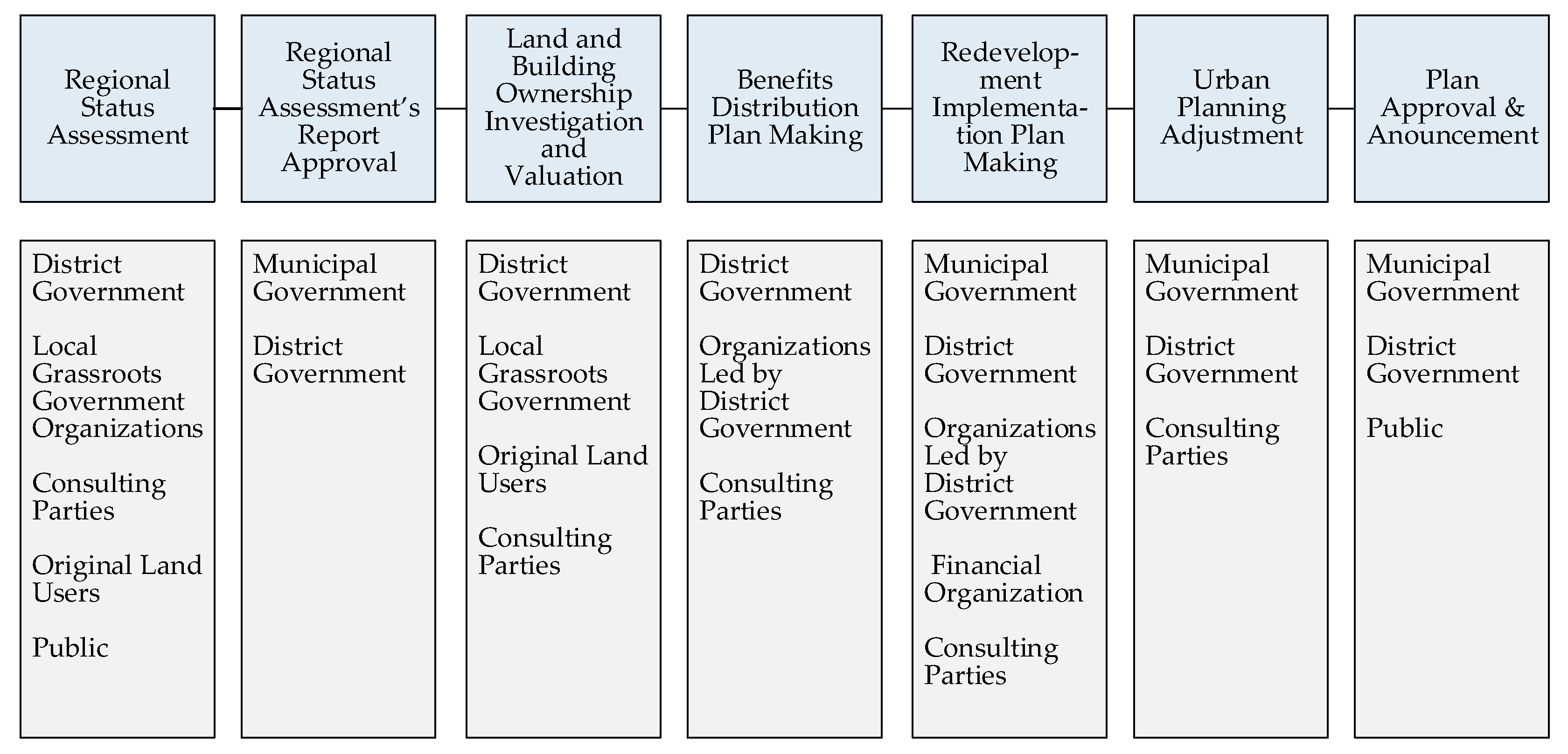

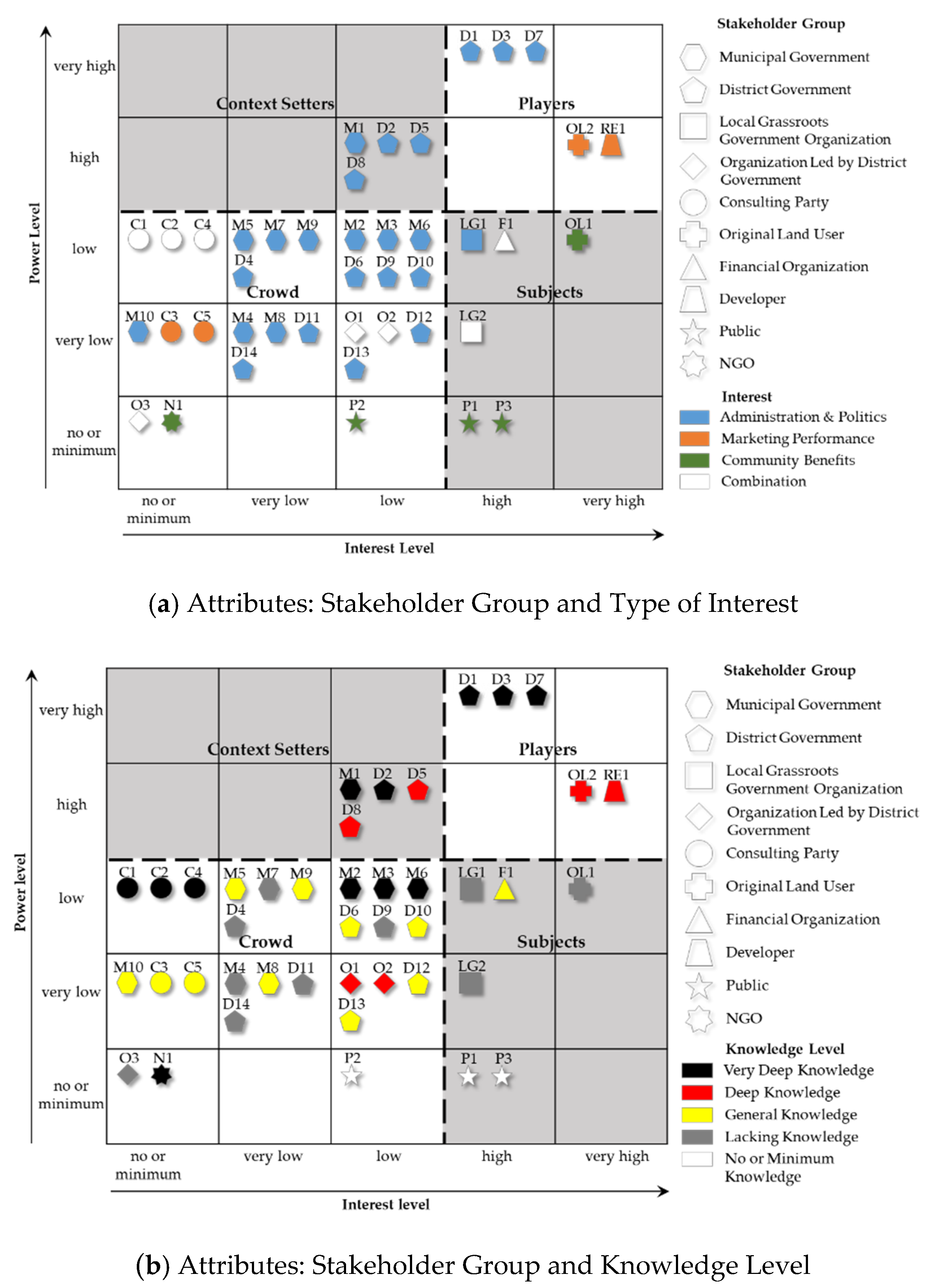

4.2. Analysis of Stakeholder Characteristics

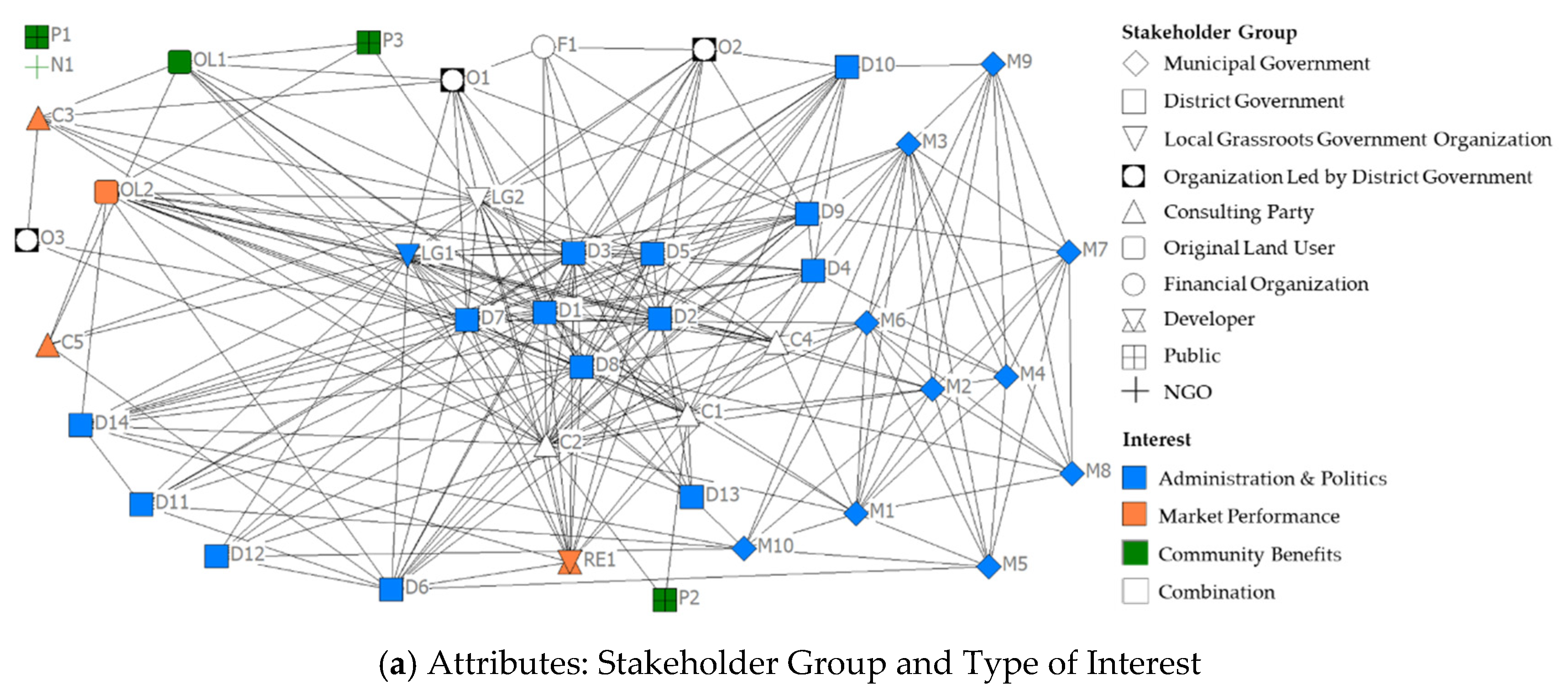

4.3. Network Structure

4.3.1. Network Structure of the Stakeholders

4.3.2. Network Structure of Different Groups

5. Discussion

5.1. Stakeholder Participation from the Perspective of SA and SNA

5.2. The Complexity of Local Government Departments

5.3. Irrational Decision-Making Procedures

5.4. Obstacles to Communication between Stakeholder Groups

5.5. Barriers to Protecting Public Interest

5.5.1. Failure to take Social Responsibility

5.5.2. The Challenges to Effective Public Participation

5.6. The Need for Specialized Laws and Regulations and Accountability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Gu, X. Reduction of industrial land beyond Urban Development Boundary in Shanghai: Differences in policy responses and impact on towns and villages. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wei, Y.D.; Huang, X.; Chen, B. Economic transition, spatial development and urban land use efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Hastings, E.M. Urban renewal in Hong Kong: Transition from development corporation to renewal authority. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C. Urban Renewal: Theory and Practice; Education Ltd: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. Factors affecting urban renewal in high-density city: Case study of Hong Kong. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2008, 134, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.F.; Yeh, A.G.O. Spatial development of producer services in the Chinese urban system. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Tang, B.; Wong, S.-W. From project to policy: Adaptive reuse and urban industrial land restructuring in Guangzhou City, China. Cities 2018, 82, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Wu, W.; Zhuang, T.; Yi, Y. Exploring the diverse expectations of stakeholders in industrial land redevelopment projects in China: The case of Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesthrige, J.W.; Wong, J.K.W.; Yuk, L.N. Conversion or redevelopment? Effects of revitalization of old industrial buildings on property values. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.M.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the “three old renewals” in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Geng, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhong, Y.; Fujita, T.; Xue, B.; Park, H.-S. Emergy-based assessment on the brownfield redevelopment of one old industrial area: A case of Tiexi in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhang, X. Redevelopment of industrial sites in the Chinese ‘villages in the city’: An empirical study of Shenzhen. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B. Practices, effects, and challenges of the inventory development pattern: The assessments and extended thoughts of urban renewal implementation in Shenzhen. City Plan. Rev. 2017, 41, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L. exploring the path of balancing individual benefits, collective benefits, and public interests in the three olds renewal. City Plan. Rev. 2018, 42, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau (SMSB). Shanghai Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2019. Available online: http://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/20200427/4aa08fba106d45fda6cb39817d961c98.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Myers, D.; Wyatt, P. Rethinking urban capacity: Identifying and appraising vacant buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2004, 32, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Ho, W.K.O. Land-use planning and market adjustment under de-industrialization: Restructuring of industrial space in Hong Kong. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, L. Post-industrial landscapes as drivers for urban redevelopment: Public versus expert perspectives towards the benefits and barriers of the reuse of post-industrial sites in urban areas. Habitat Int. 2015, 45, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. Spatial restructuring and the logic of industrial land redevelopment in urban China: II. A case study of the redevelopment of a local state-owned enterprise in Nanjing. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Lane, G. Measuring social sustainability, Best Practice from Urban Renewal in the EU, 2007/01: EIBURS Working Paper Series; Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD)–International Land Markets Group: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Dennemann, A. Urban regeneration and sustainable development in Britain: The example of the Liverpool Ropewalks Partnership. Cities 2000, 17, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B. Cultural policy and urban regeneration in Western European cities: Lessons from experience, prospects for the future. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, N. Tyranny of the median and costly consent: A reflection on the justification for participatory urban planning processes. Plan. Theory 2006, 5, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.H.Y.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. Public participation in infrastructure and construction projects in China: From an EIA-based to a whole-cycle process. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.S.F.; Xu, J.; Xue, L. Public participation in environmental impact assessment for public projects: A case of non-participation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1422–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.S.; Zhou, K.B. From unilateral decision-making to multiple participation in urban regeneration: A case study on Enning Road project in GuangZhou. City Plan. Rev. 2015, 39, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Enserink, B.; Koppenjan, J. Public participation in China: Sustainable urbanization and governance. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniato, M.; Vaccari, M.; Visvanathan, C.; Zurbrügg, C. Using social network and stakeholder analysis to help evaluate infectious waste management: A step towards a holistic assessment. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugha, R.; Varvasovszky, Z. Stakeholder analysis: A review. Health Policy Plan. 2000, 15, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.A.; Cavana, R.Y.; Jackson, L.S. Stakeholder analysis for R&D project management. RD Manag. 2002, 32, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, T.; Qian, Q.K.; Visscher, H.J.; Elsinga, M.G. Stakeholders’ expectations in urban renewal projects in China: A key step towards sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance-Borland, K.; Holley, J. Conservation stakeholder network mapping, analysis, and weaving. Conserv. Lett. 2011, 4, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) approach for assessment of urban renewal proposals. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.G.R.; Laprise, M.; Rey, E. Fostering sustainable urban renewal at the neighborhood scale with a spatial decision support system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploegmakers, H.; Beckers, P. Evaluating urban regeneration: An assessment of the effectiveness of physical regeneration initiatives on run-down industrial sites in the Netherlands. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, H. Interpretation of 798: Changes in power of representation and sustainability of industrial landscape. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5282–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.; Hu, T.S.; Fan, P. Social sustainability of urban regeneration led by industrial land redevelopment in Taiwan. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C.A. Measuring the public costs and benefits of brownfield versus greenfield development in the Greater Toronto area. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2002, 29, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, Q.; Tang, B. GIS-based framework for supporting land use planning in urban renewal: Case study in Hong Kong. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, 05014015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, W. Spatial restructuring and the logic of industrial land redevelopment in urban China: III. A case study of the redevelopment of a central state-owned enterprise in Nanjing. Cities 2020, 96, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, L.; Berry, J.; McGreal, S. An indicator-based approach to measuring sustainable urban regeneration performance: Part 1, conceptual foundations and methodological framework. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 725–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J.; Townshend, T.; Gilroy, R. The conservation of English cultural built heritage: A force for social inclusion? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2004, 10, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, J. The “roll” of the state: Government, neoliberalism and housing assistance in four advanced economies. Hous. Theory Soc. 2006, 23, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, S.; Gu, Z. The making of social injustice and changing governance approaches in urban regeneration: Stories of Enning Road, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Song, H. Transformation and upgrading of old industrial zones on collective land: Empirical study on revitalization in Nanshan. Habitat Int. 2017, 65, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, C. Renewal and redevelopment of old industrial areas in the post-industrial period. City Plan. Rev. 2011, 35, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- China Daily. The Decision on Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reforms in Brief. Available online: http://www.china.org.cn/china/third_plenary_session/2013-11/16/content_30620736.htm (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- De Bruijn, H.; Ten Heuvelhof, E. Process Management: Why Project Management Fails in Complex Decision Making Processes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B.; Wong, S.; Lau, M.C. Social impact assessment and public participation in China: A case study of land requisition in Guangzhou. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008, 28, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.H.Y.; Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M. Conflict or consensus: An investigation of stakeholder concerns during the participation process of major infrastructure and construction projects in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, J.; Leach, B. Evaluating Methods for Public Participation: Literature Review; Environment Agency: Bristol, UK, 2000.

- Hu, Y.; Lu, B. The Land Value Capture Mechanisms and their Performance in Chinese Industrial Land Regeneration. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 23, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Residential relocation under market-oriented redevelopment: The process and outcomes in urban China. Geoforum 2004, 35, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yan, S.; Wan, Z. Reflections on Improving the Urban Renewal System of Shanghai. Urban Plan. Forum 2019, 1, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Wu, F. Property-led redevelopment in post-reform China: A case study of Xintiandi redevelopment project in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. A Study of Urban Regeneration Based on Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Governance. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2013. Available online: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10611-1013043395.htm (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Bryson, J.M.; Patton, M.Q.; Bowman, R.A. Working with evaluation stakeholders: A rationale, step-wise approach and toolkit. Eval. Program Plan. 2011, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimble, R.; Wellard, K. Stakeholder methodologies in natural resource management: A review of principles, contexts, experiences and opportunities. Agric. Syst. 1997, 55, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeer, K. Guidelines for Conducting a Stakeholder Analysis; PHR: Boston, MA, USA; Abt Associates: Rockville, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Research on the Inhabitant Aspiration in the Residential District Renewal—A Case of “Ping gai po” Synthesis Renewal for Old Residentiao District in Shanghai. Ph.D. Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2006. Available online: http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10247-2006058803.htm (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Qian, Y. Policy and Practice of Urban Neighbourhood Renewal and Regeneration: What can China Learn from British Experiences? Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2009. Available online: https://www.ros.hw.ac.uk/handle/10399/2285 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Gao, J.; Chen, W.; Yuan, F. Spatial restructuring and the logic of industrial land redevelopment in urban China: I. Theoretical considerations. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y.S.; Chan, H.L. To rehabilitate or redevelop? A study of the decision criteria for urban regeneration projects. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.S.; Chen, B.Z. The strategy of the re-use of the old industry land in the yangpu old industry area-from industry yangpu to knowledge yangpu. Urban Plan Forum 2005, 1, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. Problem Analysis of Industrial Land Use in the Metropolitan Area: The Case Study of Shanghai. Urban Dev. Stud. 2016, 23, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Shanghai Chronicles (OSC). Shanghai Yearbook 2017; Office of Shanghai Chronicles: Shanghai, China, 2017. Available online: http://www.shtong.gov.cn/dfz_web/DFZ/Info?idnode=251674&tableName=userobject1a&id=411815 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Shanghai Putuo District People’s Government (SPDPG). The 13th Five-Year Space Development Strategic Plan of Putuo District, Shanghai, Shanghai Putuo District People’s Government: Putuo, Shanghai, China. 2016. Available online: http://www.shpt.gov.cn/shpt/gkgh-zhuangxian/20170607/217418.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Rozylowicz, L.; Nita, A.; Manolache, S.; Ciocanea, C.M.; Popescu, V.D. Recipe for success: A network perspective of partnership in nature conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 38, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, A.L.; Eskerod, P. Stakeholder analysis in projects: Challenges in using current guidelines in the real world. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, G.; Gilson, L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: The central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994, 9, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushove, P.; Vogel, C. Heads or tails? Stakeholder analysis as a tool for conservation area management. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. Tools for Institutional, Political, and Social Analysis of Policy Reform: A Sourcebook for Development Practitioners; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, C.; Hubacek, K.; Reed, M. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prelle, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Carrington P J. The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis; Sage Publications: Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, F.; Eden, C. Strategic management of stakeholders: Theory and practice. Long Range Plan. 2011, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, E.; Rousseau, R. Social network analysis: A powerful strategy, also for the information sciences. J. Inf. Sci. 2002, 28, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, B. Tools for Knowledge and Learning: A Guide for Development and Humanitarian Organizations; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L. The development of social network analysis. A Study Sociol. Sci. 2004, 1, 687. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Muchangos, L.S.; Tokai, A.; Hanashima, A. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis to evaluate the stakeholders of a MSWM system–A pilot study of Maputo City. Environ. Dev. 2017, 24, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation; Sage Publications: Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rongerude, J.M.; Christianson, E. Network Analysis of Affordable Housing Organizations in Polk County. 2014. Available online: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/resilientneighborhoods_reports/6/ (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Lucio, J.; De la Cruz, E.R. Affordable housing networks: A case study in the Phoenix metropolitan region. Hous. Policy Debate 2012, 22, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis; Analytic Technologies: Harvard, MA, USA, 2002; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Skaburskis, A. The origin of “wicked problems”. Plan. Theory Pract. 2008, 9, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, R. Accountability in urban regeneration partnerships: A role for design centers. Cities 2018, 72, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.L.; Chan, E.H.W. A sustainability evaluation of government-led urban renewal projects. Facilities 2008, 26, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, A.; Carlsson, L. The performance of policy networks: The relation between network structure and network performance. Policy Stud. J. 2008, 36, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö.; Crona, B.I. The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S.; Eden, C. The challenge of collaborative governance. Public Manag. Int. J. Res. Theory 2000, 2, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.; Chan, J.C.; Chui, E.W.; Wong, Y.; Lee, C.; Chau, F. Study Report Urban Renewal Policies in Asian Cities for the Urban Renewal Strategy Review; Urban Renewal Authority: Hong Kong Government: Hong Kong, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Gong, H.; Tian, T. Research on Functions of Civil Society Organizations in Solving the Social Conflicts and Disputes of the Urban House Demolition: A Theoretical Framework Based on Interests’ Game. Urban Stud. 2010, 17, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Kleinhans, R.; Van, H.M. Shantytown redevelopment projects: State-led redevelopment of declining neighbourhoods under market transition in Shenyang, China. Cities 2018, 73, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, B.; Wu, J. Value capture in industrial land renewal under the public leasehold system: A policy comparison in China. Land Use Policy 2019, 84, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.G.; Yan, X.P.; Zhou, S.H. Urban renewal unit plan of Taiwan and its enlightenment. Urban Plan. Int. 2012, 27, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- De Nooy, W. Communication in natural resource management: Agreement between and disagreement within stakeholder groups. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.F. More sustainable participation? Multi-stakeholder platforms for integrated catchment management. Water Resour. Dev. 2006, 22, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, S.; Chen, H. Revitalisation of industrial buildings in Hong Kong: New measures, new constraints? Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.M. Plight of inner city renewal restricted by present land redevelopment mechanism. City Plan. Rev. 2008, 32, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner, M.; Elsinga, M. Deadlocks and breakthroughs in urban renewal: A network analysis in Amsterdam. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2009, 24, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabham, D.C. Motivations for participation in a crowdsourcing application to improve public engagement in transit planning. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2012, 40, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Xia, N.; Ni, W. Critical success factors for the management of public participation in urban renewal projects: Perspectives from governments and the public in China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2018, 144, 04018026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Hui, C.M.; Lang, W. Collaborative workshop and community participation: A new approach to urban regeneration in China. Cities 2020, 102, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, T.; Gampfer, R.; Meng, T.; Su, Y.-S. Could more civil society involvement increase public support for climate policy-making? Evidence from a survey experiment in China. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, N. Public participation, land use and climate change governance in Thailand. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, J.; Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A.; Zbieg, A.; Żak, B. Wasting collaboration potential: A study in urban green space governance in a post-transition country. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Altrock, U. Struggling for an adaptive strategy? Discourse analysis of urban regeneration processes–A case study of Enning Road in Guangzhou City. Habitat Int. 2016, 56, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Leung, K. Enhancing life satisfaction by government accountability in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder Group | ID | Role or Position | Description of Departmental Function and Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal Government | I1-M | Government Officeholder | Work at Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources; expert in land resources management, more than 15 years of work experience with ILR projects |

| I2-M | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Economy and Informatization; urban industrial development specialist, more than 10 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| I3-M | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Development and Reform; expert in urban economics, more than 10 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| I4-M | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction Management; more than 15 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| District Government | I5-D | Government Officeholder | Work at Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources; expert in land resources management, more than 15 years of work experience in the urban land use management of ILR projects |

| I6-D | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Commerce; urban industrial development specialist, more than 15 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| I7-D | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Development and Reform; expert in urban economics, more than 10 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| I8-D | Government Officeholder | Work at Bureau of Housing Management; more than 15 years of work experience with urban land expropriation | |

| I9-D | Government Officeholder | Work at Commission of Construction and Management; more than 10 years of work experience with ILR projects | |

| Local Grassroots Government Organization | I10-LG | Deputy Mayor | Work at Town Government; grassroots work expert for ILR projects |

| I11-LG | Deputy Director | Work at Industrial Zone Management Committee; grassroots work expert in ILR projects | |

| Organization Led by District Government | I12-O | Deputy Director | Work at District Land Reserve Center; more than 10 years of work experience in urban land management of ILR projects |

| I13-O | Manager | Work at District Government-affiliated Platform Company; more than 15 years of work experience in urban land development of ILR projects | |

| Consulting Party | I14-C | Urban Planner | Work at an urban planning and design agency; more than 10 years of practical experience in ILR projects |

| I15-C | Professor | Work at the university; more than 15 years of experience in research and practice of ILR projects. | |

| I16-C | Professor | Work at the university; more than 10 years of experience in research and practice of ILR projects. | |

| I17-C | Researcher | Work at an urban research institute; researcher of ILR and conservation of industrial heritage | |

| I18-C | Director | Work at an industrial planning agency; more than 10 years of practical experience in ILR projects | |

| Original Land User | I19-OL | Entrepreneur | Original land user in state-led redevelopment model |

| I20-OL | Entrepreneur | Original land user in land user-led redevelopment model | |

| Financial Organization | I21-F | Officer | Work at Shanghai Branch of China Development Bank; more than 10 years of work experience in investment in ILR projects |

| Developer | I22-RE | Manager | Work at a real estate development company; more than 15 years of work experience in urban land development of ILR projects |

| I23-RE | Manager | Work at a real estate development company; more than 10 years of work experience in urban land development of ILR projects | |

| Public | I24-P | Worker | A migrant worker in an industrial site that will be redeveloped |

| I25-P | Manager | A manager of an enterprise tenant in an industrial site that will be redeveloped | |

| I26-P | Citizen | A resident around an industrial site that will be redeveloped | |

| NGO | I27-N | Officer | Working at an urban renewal-related nongovernmental organization; more than 10 years of work of experience in urban renewal |

| Group | Stakeholder | |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal Government | M1. Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources | M2. Commission of Development and Reform |

| M3. Commission of Economy and Informatization | M4. Commission of Science and Technology | |

| M5. Bureau of Ecology and Environment | M6. Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction Management | |

| M7. Bureau of Finance | M8. Commission of Transportation 1 | |

| M9. Bureau of State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration 1 | M10. Other Specific Sectors | |

| District Government | D1. Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources | D2. Commission of Development and Reform |

| D3. Commission of Commerce | D4. Commission of Science and Technology | |

| D5. Investment Promotion Office | D6. Bureau of Ecology and Environment | |

| D7. Bureau of Housing Management | D8. Commission of Construction and Management | |

| D9. Bureau of Finance | D10. Bureau of State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration 1 | |

| D11.Public Complaints and Proposals Office 1 | D12. Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau 1 | |

| D13. Bureau of Culture and Tourism 1 | D14. Other Specific Sectors | |

| Local Grassroots Government Organization | LG1. Town Government | LG2.Industrial Zone Management Committee |

| Organization Led by District Government | O1. District Land Reserve Center | O2. District Government-affiliated Platform Company |

| O3. Real Estate Registration Services Centre 1 | ||

| Consulting Party | C1. Urban Planning and Design Agency | C2. Scholar |

| C3. Real Estate Assessment Company | C4. Industrial Planning Agency | |

| C5. Soil and Water Environment Assessment Agency 1 | ||

| Original Land User | OL1. Original Land User in State-led Redevelopment Model | OL2. Original Land User in Land User-led Redevelopment Model |

| Financial Organization | F1. China Development Bank | |

| Developer | RE1. Real Estate Developer | |

| Public | P1. Low-end Industrial Worker | P2. Affected Surrounding Resident |

| P3. Enterprise Tenant | ||

| NGO | N1.Urban Renewal-related NGO | |

| Code 1 | Degree Centrality | Closeness Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Rank | Eigenvector | Rank | Betweenness | Rank | |

| D1 | 25.000 | 1 | 0.276 | 1 | 43.206 | 3 |

| D7 | 25.000 | 1 | 0.268 | 2 | 54.417 | 2 |

| C2 | 24.000 | 3 | 0.251 | 6 | 75.422 | 1 |

| LG1 | 23.000 | 4 | 0.256 | 5 | 32.152 | 6 |

| D3 | 22.000 | 5 | 0.257 | 3 | 25.747 | 9 |

| D2 | 22.000 | 5 | 0.257 | 3 | 26.957 | 8 |

| D8 | 21.000 | 7 | 0.243 | 7 | 37.197 | 5 |

| C1 | 20.000 | 8 | 0.217 | 10 | 41.818 | 4 |

| LG2 | 19.000 | 9 | 0.220 | 9 | 31.251 | 7 |

| D5 | 18.000 | 10 | 0.227 | 8 | 10.337 | 19 |

| D6 | 15.000 | 11 | 0.173 | 14 | 25.089 | 10 |

| D9 | 15.000 | 11 | 0.181 | 13 | 19.809 | 14 |

| OL2 | 15.000 | 11 | 0.191 | 11 | 20.184 | 13 |

| C4 | 14.000 | 14 | 0.172 | 15 | 9.657 | 22 |

| M3 | 14.000 | 14 | 0.104 | 24 | 23.228 | 11 |

| M2 | 13.000 | 16 | 0.091 | 28 | 18.603 | 16 |

| M6 | 13.000 | 16 | 0.096 | 25 | 22.348 | 12 |

| M1 | 13.000 | 16 | 0.092 | 27 | 19.270 | 15 |

| RE1 | 13.000 | 16 | 0.186 | 12 | 1.305 | 35 |

| D10 | 13.000 | 16 | 0.169 | 16 | 15.012 | 17 |

| D14 | 12.000 | 21 | 0.160 | 17 | 8.507 | 23 |

| O2 | 11.000 | 22 | 0.152 | 18 | 1.991 | 33 |

| O1 | 10.000 | 23 | 0.123 | 20 | 4.789 | 26 |

| D4 | 10.000 | 23 | 0.126 | 19 | 9.732 | 21 |

| OL1 | 10.000 | 23 | 0.111 | 22 | 9.804 | 20 |

| M10 | 9.000 | 26 | 0.056 | 32 | 13.229 | 18 |

| M7 | 9.000 | 26 | 0.046 | 33 | 5.077 | 25 |

| D11 | 8.000 | 28 | 0.105 | 23 | 3.211 | 29 |

| D13 | 8.000 | 28 | 0.115 | 21 | 3.651 | 28 |

| M9 | 8.000 | 28 | 0.043 | 36 | 3.122 | 31 |

| M4 | 8.000 | 28 | 0.040 | 37 | 3.654 | 27 |

| M5 | 8.000 | 28 | 0.044 | 35 | 5.853 | 24 |

| D12 | 7.000 | 33 | 0.093 | 26 | 3.135 | 30 |

| C3 | 7.000 | 33 | 0.079 | 29 | 2.289 | 32 |

| M8 | 7.000 | 33 | 0.045 | 34 | 1.962 | 34 |

| F1 | 6.000 | 36 | 0.078 | 30 | 0.274 | 37 |

| C5 | 5.000 | 37 | 0.059 | 31 | 0.583 | 36 |

| O3 | 3.000 | 38 | 0.037 | 38 | 0.000 | 39 |

| P3 | 3.000 | 38 | 0.033 | 39 | 0.125 | 38 |

| P2 | 2.000 | 40 | 0.029 | 40 | 0.000 | 39 |

| P1 | 0.000 | 41 | 0.000 | 41 | 0.000 | 39 |

| N1 | 0.000 | 41 | 0.000 | 42 | 0.000 | 39 |

| Category | Group | Degree | Closeness (Eigenvector) | Betweenness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Stakeholder Group | Municipal Government | 10.200 | 0.066 | 11.635 |

| District Government | 15.786 | 0.189 | 20.429 | |

| Local Administrative Organization | 21.000 | 0.238 | 31.702 | |

| Organization Led by District Government | 8.000 | 0.104 | 2.260 | |

| Consulting Party | 14.000 | 0.156 | 26.098 | |

| Original Land User | 12.500 | 0.151 | 14.994 | |

| Financial Institution | 6.000 | 0.078 | 0.274 | |

| Developer | 13.000 | 0.186 | 1.305 | |

| Public | 1.667 | 0.021 | 0.042 | |

| NGO | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Type of Interest | Administration & Politics | 13.840 | 0.143 | 17.380 |

| Marketing Performance | 11.667 | 0.129 | 6.271 | |

| Community Benefits | 3.000 | 0.035 | 1.986 | |

| Combination | 13.375 | 0.156 | 20.650 | |

| Knowledge Level | Very Deep | 17.083 | 0.173 | 30.056 |

| Deep | 14.667 | 0.187 | 12.634 | |

| General | 8.455 | 0.087 | 6.811 | |

| Lacking | 11.700 | 0.128 | 12.320 | |

| No or Minimum | 1.667 | 0.021 | 0.042 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; He, F.; Zhuang, T.; Yi, Y. Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in the Decision-Making of Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: The Case of Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249206

Wu W, He F, Zhuang T, Yi Y. Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in the Decision-Making of Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: The Case of Shanghai. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249206

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Wendong, Fang He, Taozhi Zhuang, and Yuan Yi. 2020. "Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in the Decision-Making of Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: The Case of Shanghai" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 24: 9206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249206

APA StyleWu, W., He, F., Zhuang, T., & Yi, Y. (2020). Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in the Decision-Making of Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: The Case of Shanghai. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249206