Health-Related Quality of Life and Medical Resource Use in Patients with Osteoporosis and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

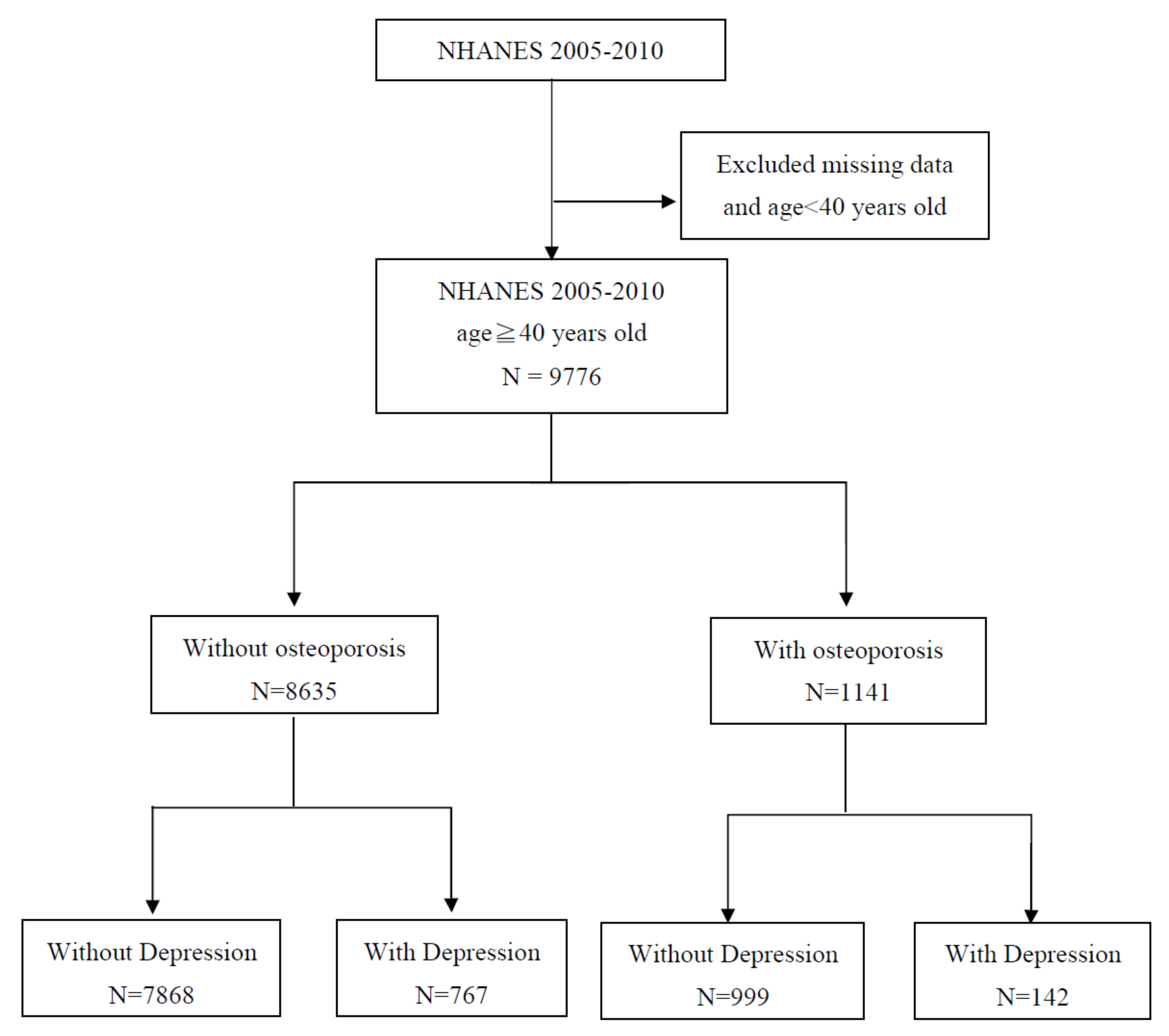

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| HRQoL | health-related quality of life |

| O+ | osteoporosis-positive(+) |

| O− | osteoporosis-negative(−) |

| D+ | epression-positive(+) |

| D− | epression-negative(−) |

| OR | odds ratio |

| AOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| ADLs | activities of daily living (ADLs) |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| NCHS | National Center for Health Statistics |

| RIP | ratio of family income to poverty |

| BMI | body mass index |

References

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedbom, A.; Hernlund, E.; Ivergard, M.; Compston, J.; Cooper, C.; Stenmark, J.; McCloskey, E.V.; Jönsson, B.; Kanis, J.A. The EU review panel of the IOF. Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch. Osteoporos. 2013, 8, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson, T.; Nelson, S.D.; Newbold, J.; Nelson, R.E.; LaFleur, J. The clinical epidemiology of male osteoporosis: a review of the recent literature. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wade, S.W. Estimating prevalence of osteoporosis: examples from industrialized countries. Arch. Osteoporos. 2014, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizza, G.; Primma, S.; Coyle, M.; Gourgiotis, L.; Csako, G. Depression and osteoporosis: A research synthesis with meta-analysis. Horm. Metab. Res. Horm. Und Stoffwechs. Horm. Et Metab. 2010, 42, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizza, G.; Primma, S.; Csako, G. Depression as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. Tem. 2009, 20, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S. Central control of bone remodelling. J. Neuroendocr. 2008, 20, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonijevic, I.A.; Murck, H.; Frieboes, R.M.; Horn, R.; Brabant, G.; Steiger, A. Elevated nocturnal profiles of serum leptin in patients with depression. J. Psychiatry Res. 1998, 32, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Deak, A.; Cizza, G.; Sternberg, E. Brain-immune interactions and disease susceptibility. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005, 10, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, J.A.; Nicholson, G.C.; Ng, F.; Henry, M.J.; Williams, L.J.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Hodge, J.M.; Dodd, S.; Kapczinski, F.; Gama, C.S. Oxidative stress may be a common mechanism linking major depression and osteoporosis. Acta Neuropsychiatry 2008, 20, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, W.J.; Lips, P.; Dik, M.G.; Deeg, D.J.; Beekman, A.T.; Penninx, B.W. Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C.H.; Larsen, L.W.; Sorensen, A.M.; Halling-Sorensen, B.; Styrishave, B. The six most widely used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors decrease androgens and increase estrogens in the H295R cell line. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diem, S.J.; Blackwell, T.L.; Stone, K.L.; Yaffe, K.; Haney, E.M.; Bliziotes, M.M.; Ensrud, K.E. Use of antidepressants and rates of hip bone loss in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1240–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcum, Z.A.; Perera, S.; Thorpe, J.M.; Switzer, G.E.; Castle, N.G.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Phillips, C.L.; Rubin, S. Antidepressant Use and Recurrent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Findings From the Health ABC Study. Ann. Pharm. 2016, 50, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Malley, C.D.; Tran, N.; Zapalowski, C.; Daizadeh, N.; Olenginski, T.P.; Cauley, J.A. Multimorbidity in women with and without osteoporosis: Results from a large US retrospective cohort study 2004–2009. Osteoporos. Int. A J. Establ. Result Coop. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 2014, 25, 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Shen, C.; Sambamoorthi, U. Excess risk of chronic physical conditions associated with depression and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronijevic, M.; Petronijevic, N.; Ivkovic, M.; Stefanović, D.; Radonjić, N.; Glišić, B.; Ristić, G.; Damjanović, A.; Paunović, V. Low bone mineral density and high bone metabolism turnover in premenopausal women with unipolar depression. Bone 2008, 42, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussolino, M.E. Depression and hip fracture risk: The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Public Health Rep. 2005, 120, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katon, W.; Lin, E.H.; Kroenke, K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2007, 29, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauma, P.H.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Williams, L.J.; Tuppurainen, M.T.; Kroger, H.P.; Honkanen, R.J. Life satisfaction and bone mineral density among postmenopausal women: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Psychosom. Med. 2014, 76, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakarinen, M.; Tuomainen, I.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Sinikallio, S.; Lehto, S.M.; Airaksinen, O.; Viinamäki, H.; Aalto, T. Life dissatisfaction is associated with depression and poorer surgical outcomes among lumbar spinal stenosis patients: a 10-year follow-up study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. Int. Z. Fur Rehabil. Rev. Int. De Rech. De Readapt. 2016, 39, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, Hy.; Kim, Ki.; Lee, Ji.; Yang, S.-H. Association between Osteoporotic Fractures and Quality of Life Based on the Korean Community Health Survey of 2010. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 3325–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jean, S.; Bessette, L.; Belzile, E.L.; Davison, K.S.; Candas, B.; Morin, S.; Dodin, S.; Brown, J.P. Direct medical resource utilization associated with osteoporosis-related nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, T.A.; Pieber, K.; Blasche, G.; Dorner, T.E. Health care utilisation in subjects with osteoarthritis, chronic back pain and osteoporosis aged 65 years and more: mediating effects of limitations in activities of daily living, pain intensity and mental diseases. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2014, 164, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Wu, C.C.; Jung, W.T.; Lin, C.Y. The associations among lead exposure, bone mineral density, and FRAX score: NHANES, 2013 to 2014. Bone 2019, 128, 115045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, A.C.; Sarafrazi Isfahani, N.; Fan, B.; Shepherd, J.A. FRAX-based Estimates of 10-year Probability of Hip and Major Osteoporotic Fracture Among Adults Aged 40 and Over: United States, 2013 and 2014. Natl. Health Stat. Report. 2017, 103, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, T.D.; Di Pace, B.S. Is Self-Reported Sleep Duration Associated with Osteoporosis? Data from a 4-Year Aggregated Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revicki, D.A.; Kleinman, L.; Cella, D. A history of health-related quality of life outcomes in psychiatry. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Schatzberg, A.F. Using chronic pain to predict depressive morbidity in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobocki, P.; Ekman, M.; Agren, H.; Krakau, I.; Runeson, B.; Mårtensson, B.; Jönsson, B. Health-related quality of life measured with EQ-5D in patients treated for depression in primary care. Value Health: J. Int. Soc. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2007, 10, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, L.; Pan, A.W.; Hsiung, P.C. Quality of life for patients with major depression in Taiwan:A model-based study of predictive factors. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 168, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.W.; Chiu, H.F.; Chien, W.T.; Thompson, D.R.; Lam, L. Quality of life in Chinese elderly people with depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villoro, R.; Merino, M.; Hidalgo-Vega, A. Quality of life and use of health care resources among patients with chronic depression. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2016, 7, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamienski, M.; Tate, D.; Vega, C.P.T.M. The Silent Thief Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis. Orthop Nurs. 2011, 30, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urushihara, H.; Yoh, K.; Hamaya, E.; Taketsuna, M.; Tanaka, K. Responsiveness of the Japanese Osteoporosis Quality of Life questionnaire in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, J.D.; Adami, S.; Gehlbach, S.; Anderson, F.A., Jr.; Boonen, S.; Chapurlat, R.D.; Compston, J.E.; Cooper, C.; Delmas, P.; Díez-Pérez, A.; et al. Impact of prevalent fractures on quality of life: Baseline results from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips, P.; van Schoor, N.M. Quality of life in patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. A J. Establ. Result Coop. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 2005, 16, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.R.; Sornay-Rendu, E.; Chandler, J.M.; Duboeuf, F.; Girman, C.J.; Delmas, P.D. The impact of osteoporosis on quality-of-life: the OFELY cohort. Bone 2002, 31, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J.; Guyatt, G.H.; Adachi, J.D.; Epstein, R.S.; Juniper, E.F.; Austin, P.A.; Clifton, J.; Rosen, C.J.; Kessenich, C.R.; Stock, J.L.; et al. Development and validation of the mini-osteoporosis quality of life questionnaire (OQLQ) in osteoporotic women with back pain due to vertebral fractures. Osteoporosis Quality of Life Study Group. Osteoporos. Int. A J. Establ. Result Coop. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 1999, 10, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sari, U.A.; Tobias, J.; Clark, E. Health-related quality of life in older people with osteoporotic vertebral fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. A J. Establ. Result Coop. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 2016, 27, 2891–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bullard, K.M.; Gregg, E.W.; Beckles, G.L.; Williams, D.E.; Barker, L.E.; Albright, A.L.; Imperatore, G. Access to health care and control of ABCs of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVoe, J.E.; Fryer, G.E.; Phillips, R.; Green, L. Receipt of preventive care among adults: insurance status and usual source of care. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrew, J.M.; DeFriese, G.H.; Carey, T.S.; Ricketts, T.C.; Biddle, A.K. The effects of having a regular doctor on access to primary care. Med. Care 1996, 34, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T.D.; Di Pace, B.S.; Ullal, J. Osteoporosis treatment disparities: A 6-year aggregate analysis from national survey data. Osteoporos. Int. A J. Establ. Result Coop. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 2014, 25, 2199–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orszag, P.R.; Ellis, P. Addressing rising health care costs—A view from the Congressional Budget Office. New Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1885–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J. The cost implications of health care reform. New Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2050–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mausbach, B.T.; Irwin, S.A. Depression and healthcare service utilization in patients with cancer. Psycho Oncol. 2017, 26, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagy, R.; Amitai, M.; Weizman, A.; Aizenberg, D. Levels of depression and satisfaction with life as indicators of health services consumption. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2016, 20, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merianos, A.L.; Jandarov, R.A.; Mahabee-Gittens, E.M. Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Pediatric Healthcare Visits and Hospitalizations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, R.S.; Baltrus, P.; Ye, J.; Rust, G. Prevalence, treatment, and control of depressive symptoms in the United States: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2005–2008. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2011, 24, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | O−/D− | O+/D− | O−/D+ | O+/D+ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 7868 (80.48) | 999 (10.22) | 767 (7.85) | 142 (1.45) | |

| Year | |||||

| 2005–2006 | 2223 (83.04) | 251 (6.28) | 168 (9.38) | 35 (1.3) | 0.003 |

| 2007–2008 | 2798 (79.11) | 387 (8.31) | 294 (10.94) | 58 (1.64) | |

| 2009–2010 | 2847 (79.93) | 361 (8.56) | 305 (10.13) | 49 (1.38) | |

| Demographic | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 4314 (54.83) | 201 (20.12) | 333 (43.42) | 22 (15.49) | <0.001 |

| Female | 3554 (45.17) | 798 (79.88) | 434 (56.58) | 120 (84.51) | |

| Age | 59.15 ± 12.42 | 69.53 ± 10.69 | 55.88 ± 11.22 | 64.01 ± 11.21 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4042 (51.37) | 649 (64.96) | 349 (45.50) | 75 (52.82) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1653 (21.01) | 114 (11.41) | 168 (21.90) | 16 (11.27) | |

| Hispanic (Mexican American or other) | 1908 (24.25) | 200 (20.02) | 218 (28.42) | 46 (32.39) | |

| Other (including multiracial) | 265 (3.37) | 36 (3.60) | 32 (4.17) | 5 (3.52) | |

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 2293 (29.14) | 321 (32.13) | 328 (42.76) | 72 (50.70) | <0.001 |

| High school or equivalent | 1858 (23.61) | 267 (26.73) | 174 (22.69) | 34 (23.94) | |

| College graduate or above | 3717 (47.24) | 411 (41.14) | 265 (34.55) | 36 (25.35) | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 4844 (61.57) | 496 (49.65) | 355 (43.68) | 50 (35.21) | <0.001 |

| Never married | 532 (6.76) | 44 (4.40) | 80 (10.43) | 11 (7.75) | |

| Widowed | 843 (10.71) | 301 (30.13) | 90 (11.73) | 37 (26.06) | |

| Living with partner, separated, or divorced | 1649 (20.96) | 158 (15.82) | 262 (34.16) | 44 (30.99) | |

| Family poverty index ratio (RIP) | 2.79 1.56 | 2.47 1.44 | 1.89 1.37 | 1.76 1.22 | <0.001 |

| General health condition | |||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||||

| <18.5 | 88 (1.12) | 28 (2.80) | 13 (1.69) | 2 (1.41) | <0.001 |

| 18.5–25.0 | 1705 (21.67) | 392 (39.24) | 150 (19.56) | 41 (28.87) | |

| 25.0 | 6075 (77.21) | 579 (57.96) | 604 (78.75) | 99 (69.72) | |

| Cigarette smoking | 3973 (50.50) | 473 (47.35) | 469 (61.15) | 92 (64.79) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinking | 5550 (70.54) | 560 (56.06) | 525 (68.45) | 72 (50.70) | <0.001 |

| Sleep disorders | 604 (7.68) | 82 (8.21) | 179 (23.34) | 46 (32.39) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3560 (45.25) | 540 (54.05) | 413 (53.85) | 95 (66.90) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1232 (15.66) | 168 (16.82) | 172 (22.43) | 46 (32.39) | <0.001 |

| Variable | O−/D− | O+/D− | O−/D+ | O+/D+ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physically unhealthy days † | 3.90 8.87 | 5.67 11.25 | 13.93 13.31 | 16.78 15.42 | <0.001 |

| Mentally unhealthy days ‡ | 2.60 7.21 | 3.20 8.15 | 17.61 14.15 | 17.82 16.78 | <0.001 |

| Totally unhealthy days # | 5.85 9.51 | 7.62 10.73 | 22.73 10.59 | 23.33 9.94 | <0.001 |

| Limited activity days § | 1.63 6.64 | 2.65 8.52 | 10.79 12.94 | 12.85 14.01 | <0.001 |

| Health status | |||||

| Excellent | 729 (9.27) | 66 (6.61) | 11 (1.43) | 0 (0.00) | <0.001 |

| Very good | 2183 (27.75) | 236 (23.62) | 50 (6.52) | 4 (2.82) | |

| Good | 3156 (40.11) | 383 (38.34) | 212 (27.64) | 29 (20.42) | |

| Fair | 1587 (20.17) | 256 (25.63) | 325 (42.37) | 57 (40.14) | |

| Poor | 213 (2.71) | 58 (5.81) | 169 (22.03) | 52 (36.42) | |

| Type of routine healthcare place visited | |||||

| Clinic, health center, or others | 2689 (34.18) | 248 (24.82) | 328 (42.76) | 55 (38.13) | <0.001 |

| Doctor’s office or HMO | 5179 (65.82) | 751 (75.18) | 439 (57.24) | 87 (61.27) | |

| Number of healthcare visits/year | |||||

| 0–3 visits | 4521 (57.46) | 379 (37.94) | 299 (38.98) | 29 (20.42) | <0.001 |

| 4 visits | 3347 (42.54) | 620 (62.06) | 468 (61.02) | 113 (79.58) | |

| Times hospitalized overnight previous year | |||||

| Yes | 993 (12.62) | 200 (20.02) | 182 (23.73) | 56 (39.44) | <0.001 |

| No | 6875 (87.38) | 799 (79.98) | 585 (76.27) | 86 (60.56) | |

| Univaritate | Multivariate * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | p | Beta | p | |

| Physically unhealthy days | ||||

| O+/D+ | 11.90 | <0.001 | 10.94 | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 9.63 | <0.001 | 9.02 | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 0.69 | 0.041 | 1.17 | <0.001 |

| O−/D− | reference | reference | ||

| Mentally unhealthy days | ||||

| O+/D+ | 13.96 | <0.001 | 14.13 | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 14.70 | <0.001 | 14.11 | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | −0.96 | 0.002 | 0.48 | 0.105 |

| O−/D− | reference | reference | ||

| Totally unhealthy days | ||||

| O+/D+ | 15.95 | <0.001 | 15.13 | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 16.41 | <0.001 | 15.28 | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 0.01 | 0.976 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| O−/D− | reference | reference | ||

| Activity limitation days | ||||

| O+/D+ | 10.38 | <0.001 | 10.25 | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 8.88 | <0.001 | 8.58 | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 0.04 | 0.885 | 0.83 | 0.002 |

| O−/D− | reference | reference | ||

| OR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) * | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O+/D+ | 8.90 (6.01–13.17) | <0.001 | 7.40 (4.80–11.40) | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 5.52 (4.73–6.45) | <0.001 | 4.79 (4.02–5.72) | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | 0.007 | 1.61 (1.35–1.91) | <0.001 |

| O−/D− | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | AOR (95% CI) * | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor’s office or HMO | ||||

| O+/D+ | 0.81 (0.58, 1.14) | 0.227 | 0.88 (0.61, 1.26) | 0.473 |

| O−/D+ | 0.67 (0.57, 0.77) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.81, 1.13) | 0.622 |

| O+/D− | 1.63 (1.40, 1.89) | <0.001 | 1.15 (0.97, 1.36) | 0.107 |

| O−/D− | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Healthcare visits 4/year | ||||

| O+/D+ | 4.57 (3.03, 6.88) | <0.001 | 3.25 (2.12, 5.00) | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 1.89 (1.63, 2.20) | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.76, 2.47) | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 2.02 (1.77, 2.31) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.35, 1.82) | <0.001 |

| O−/D− | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Hospitalized overnight last year | ||||

| O+/D+ | 3.91 (2.78, 5.50) | <0.001 | 2.71 (1.89, 3.90) | <0.001 |

| O−/D+ | 1.93 (1.62, 2.31) | <0.001 | 1.80 (1.48, 2.18) | <0.001 |

| O+/D− | 1.53 (1.30, 1.81) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.10, 1.59) | 0.003 |

| O−/D− | 1.00 | 1.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weng, S.-F.; Hsu, H.-R.; Weng, Y.-L.; Tien, K.-J.; Kao, H.-Y. Health-Related Quality of Life and Medical Resource Use in Patients with Osteoporosis and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031124

Weng S-F, Hsu H-R, Weng Y-L, Tien K-J, Kao H-Y. Health-Related Quality of Life and Medical Resource Use in Patients with Osteoporosis and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031124

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeng, Shih-Feng, Hui-Ru Hsu, Yao-Lin Weng, Kai-Jen Tien, and Hao-Yun Kao. 2020. "Health-Related Quality of Life and Medical Resource Use in Patients with Osteoporosis and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031124

APA StyleWeng, S.-F., Hsu, H.-R., Weng, Y.-L., Tien, K.-J., & Kao, H.-Y. (2020). Health-Related Quality of Life and Medical Resource Use in Patients with Osteoporosis and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031124