Understanding the Meaning of Conformity to Feminine Norms in Lifestyle Habits and Health: A Cluster Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement Instruments

2.2.1. Conformity to Gender Role Indicators

2.2.2. Social Support Measures

2.2.3. Lifestyle Indicators

2.2.4. Covariates

2.3. Ethical Procedures

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

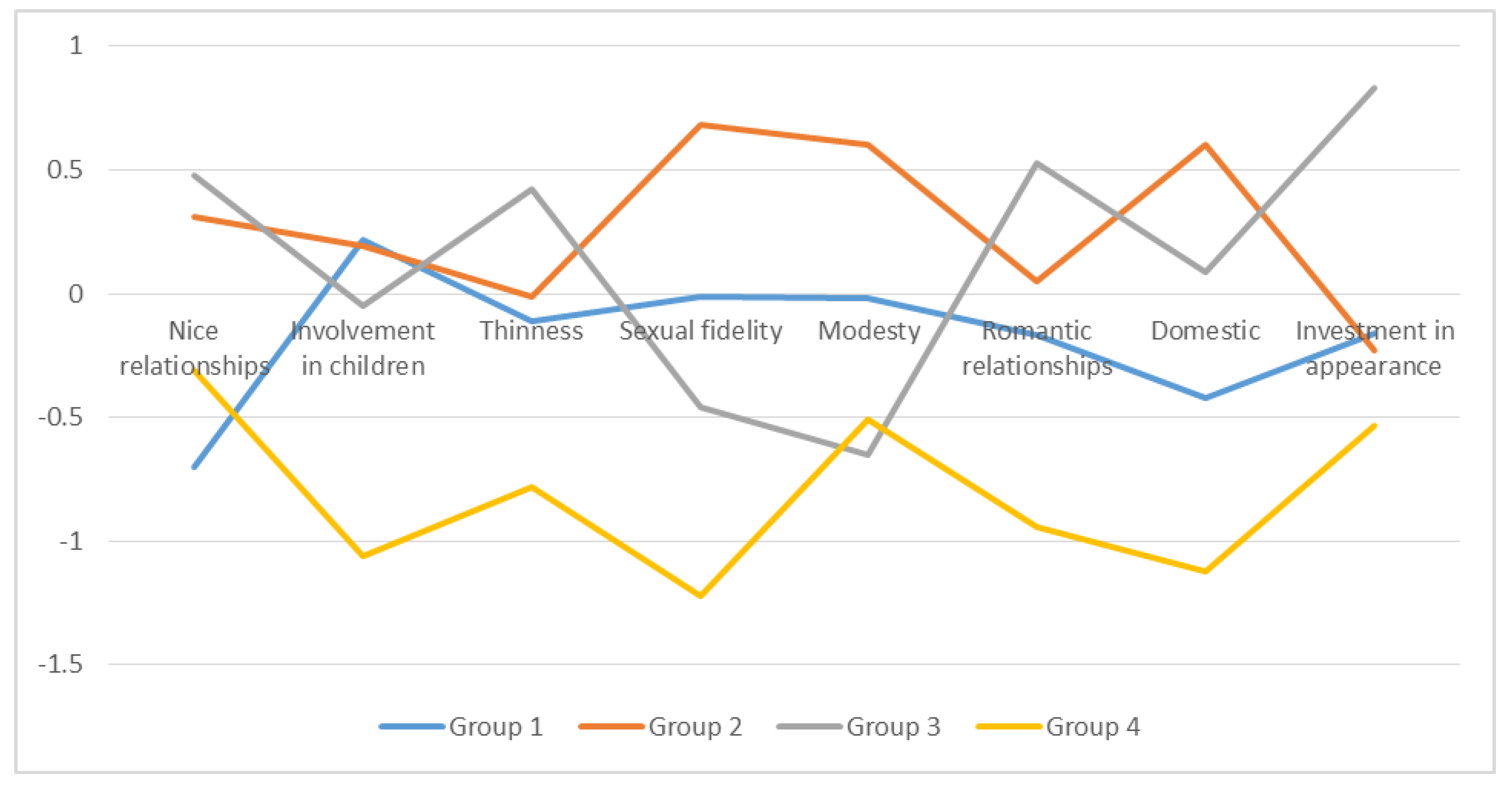

3.3. Cluster Analysis and Lifestyle Indicators

4. Discussion

Patterns of Femininity and Lifestyles

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez–López, M.D.P.; Cuellar–Flores, I.; Dresch, V. The impact of gender roles on health. Women Health 2012, 52, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlfs, I.; Borrell, C.; Fonseca, M.D.C. Género, desigualdades y salud pública: Conocimientos y desconocimientos. Gac. Sanit. 2000, 14, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Malmusi, D.; Vives, A.; Benach, J.; Borrell, C. Gender inequalities in health: Exploring the contribution of living conditions in the intersection of social class. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman, L.A.; Phelan, J.E. The effect of priming gender roles on women’s implicit gender beliefs and career aspirations. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 41, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Morray, E.B.; Coonerty-Femiano, A.; Ludlow, L.H.; Slattery, S.M.; Smiler, A. Development of the conformity to feminine norms inventory. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, C. Gendering the European Digital Agenda. J. Inf. 2016, 6, 403–435. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, G.; Buiting, S. Gender differences in leadership styles and the impact within corporate boards. In The Commonwealth Secretariat Social Transformation Programmes Division; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bettio, F.; Verashchagina, A.; Mairhuber, I.; Kanjuo-Mrčela, A. Gender Segregation in the Labour Market: Root Causes, Implications and Policy Responses in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis, S.; Hollows, J. Feminism, Domesticity and Popular Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Varì, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; D’Amore, A.; Giovannini, C.; Gessani, S.; Masella, R. Gender-related differences in lifestyle may affect health status. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore Sanita 2016, 52, 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Burns, S.M.; Syzdek, M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, S.A.; Ailshire, J.A. Gender and time for sleep among US adults. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 78, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheochari, S.; Arber, S. Lack of sleep, work and the long hours culture: Evidence from the UK Time Use Survey. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.L.; Lee, K.A.; Lee, S.-Y. Sleep patterns and fatigue in new mothers and fathers. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2004, 5, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochschild, A.; Machung, A. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Y.D.; Brown, W.J. Determinants of active leisure for women with young children—An “ethic of care” prevails. Leis. Sci. 2005, 27, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, M.R.; Araújo, C.L.P.; Reichert, F.F.; Siqueira, F.V.; da Silva, M.C.; Hallal, P.C. Gender differences in leisure-time physical activity. Int. J. Public Health 2007, 52, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Yeh, M.C.; Chen, Y.-M.; Huang, L.-H. Physical activity status and gender differences in community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases. J. Nurs. Res. 2010, 18, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.; Niemann, S.; Abel, T. Gender differences in physical activity and fitness—Association with self-reported health and health-relevant attitudes in a middle-aged Swiss urban population. J. Public Health 2004, 12, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kilgour, L.; Parker, A. Gender, physical activity and fear: Women, exercise and the great outdoors. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2013, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; Harrolle, M.G.; Kelley, K. Gender differences in self-report physical activity and park and recreation facility use among Latinos in Wake County, North Carolina. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, S49–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, M.P.; Flores, I.C.; Dresch, V.; Aparicio-Garcia, M. Conformity to feminine gender norms in the Spanish population. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2009, 37, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, A.; Ahmed, T.; Freire, A.D.N.F.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; Guerra, R.O. Depression, Sex and Gender Roles in Older Adult Populations: The International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Vafaei, A.; Auais, M.; Guralnik, J.; Zunzunegui, M.V. Gender roles and physical function in older adults: Cross-sectional analysis of the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellón Saameño, J.; Delgado Sánchez, A.; Luna del Castillo, J.D.D.; Lardelli Claret, P. Validez y fiabilidad del cuestionario de apoyo social funcional Duke-UNC-11. Atención Primaria 1996, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Expósito, L.; Amador-Campos, J.A.; Gómez-Benito, J.; Lalucat-Jo, L. Validation of the modified DUKE-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire in patients with schizophrenia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, E.; Abid, M.; Zhang, H.; Cui, W.; Hasson, S.U. Domestic water buffaloes: Access to surface water, disease prevalence and associated economic losses. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 154, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z.; Weijun, C.; Zhang, H. The public policy of agricultural land allotment to agrarians and its impact on crop productivity in Punjab province of Pakistan. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, A. Technical efficiency of egg production in Osun State. Int. J. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2008, 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- AA, K.H.; Razman, M.; Jamalludin, A.; Nasreen, E.; Phyu, H.M.; SweSwe, L.; Hafizah, P. Knowledge, attitude and practice on dengue among adult population in Felda Sungai Pancing Timur, Kuantan, Pahang. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 2017, 16, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wauters, E.; Bielders, C.; Poesen, J.; Govers, G.; Mathijs, E. Adoption of soil conservation practices in Belgium: An examination of the theory of planned behaviour in the agri-environmental domain. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.W. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. Am. J. Sociol. 2002, 107, 1065–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, P. Marriage, the costs of children, and gender inequality. In The Ties that Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Domenico, D.M.; Jones, K.H. Career aspirations of women in the 20th century. J. Career Tech. Educ. 2006, 22, n2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M. Married women, work, and values. Mon. Lab. Rev. 2000, 123, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, M.L. Breaking the glass ceiling: Structural, cultural, and organizational barriers preventing women from achieving senior and executive positions. In Perspectives in Health Information Management/AHIMA; American Health Information Management Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. World Development Indicators 2014; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, M.O. Mujer y dictadura franquista. Aposta. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 2006, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, J.C.M. La Familia Como Medio de Inclusión de la Mujer en la Sociedad Franquista. 2007, p. 193. Available online: http://hispanianova.rediris.es (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Sánchez, C. La familia: Concepto, cambios y nuevos modelos. Revista La Revue du REDIF 2008, 2, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Schulenberg, J.E. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010. Volume I: Secondary School Students; Institute for Social Research: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rieker, P.P.; Bird, C.E. Rethinking gender differences in health: Why we need to integrate social and biological perspectives. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2005, 60, S40–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, J.M.; Yoon, S.-Y.; World Health Organization. Gender, Women, and the Tobacco Epidemic; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moya, J.G. El alcoholismo femenino, una verdad oculta. Trastor. Adict. 2006, 8, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Moya, J.; Arnal Gómez, A.; Martínez Vilanova, A.M.; Muñoz Rodríguez, D. Mujeres y uso del alcohol en las sociedades contemporáneas. Revista Española Drogodependencias 2010, 35, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pujadas i Martí, X.; Garay Ibañez de Elejalde, B.; Gimeno Marco, F.; Llopis Goig, R.; Ramírez Macías, G.; Parrilla Fernández, J.M. Mujeres y deporte durante el franquismo (1939–1975). Estudio piloto sobre la memoria oral de las deportistas = Women and sport during francoism (1939–1975). Pilot study on oral memory of sportswomen. Mater. Para Historia Deporte 2012, 10, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas, J.M. Actividad física y juventud en el franquismo (1937–1961). Int. J. Med. Sci. Phys. Act. Sport 2014, 14, 427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo-Salguero, A.; García-Martínez, J.M.Á.; Monteoliva, A. Differences between and within genders in gender role orientation according to age and level of education. Sex Roles 2008, 58, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reevy, G.M.; Maslach, C. Use of social support: Gender and personality differences. Sex Roles 2001, 44, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Farmer, S.J.; Glazer, S.; Gudanowski, D.M.; Nair, V.N. The enigma of social support and occupational stress: Source congruence and gender role effects. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2003, 8, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, W.A.; Fuehrer, A. Effects of gender and gender role identification of participant and type of social support resource on support seeking. Sex Roles 1993, 28, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artázcoz, L.; Borrell, C.; Rohlfs, I.; Beni, C.; Moncada, A.; Benach, J. Trabajo doméstico, género y salud en población ocupada. Gac. Sanit. 2001, 15, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artazcoz, L.; Escribà-Agüir, V.; Cortès, I. Género, trabajos y salud en España. Gac. Sanit. 2004, 18, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, P. Fathers’ child care involvement and children’s age in Spain: A time use study on differences by education and mothers’ employment. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 30, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guner, N.; Kaya, E.; Sánchez-Marcos, V. Gender gaps in Spain: Policies and outcomes over the last three decades. SERIEs 2014, 5, 61–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez, A.M. Family and gender roles in Spain from a comparative perspective. Eur. Soc. 2010, 12, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C.; Recio, A. Time, work and gender in Spain. Time Soc. 2001, 10, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaquer, L.; Mínguez, A.M.; López, T.C. Changing family models: Emerging new opportunities for fathers in Catalonia (Spain). In Balancing Work and Family in a Changing Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Gonzalo, S.; Aparicio, M.; Estaban-Gonzalo, L. Employment status, gender and health in Spanish women. Women Health 2018, 58, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Family and gender roles: How attitudes are changing. Arxius de Ciències Socials 2006, 15, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.J.; Jurado, T.; Naldini, M. Introduction: Interpreting the transformation of gender inequalities in Southern Europe. In Gender Inequalities in Southern Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 10–40. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sáez, M.; Morales, J.F.; Lisbona, A. Evolution of gender stereotypes in Spain: Traits and roles. Span. J. Psychol. 2008, 11, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovi, F. The relationship between education and levels of trust and tolerance in Europe1. Br. J. Sociol. 2012, 63, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz, J.; Peña-Suárez, E.; de la Roca, Y.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Cabal, Á.L.; García-Cueto, E. Organizational climate in Spanish Public Health Services: Administration and Services Staff. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Caramés, A. Family policies in Spain. In Handbook of Family Policies across the Globe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Grau, M. Clouds over Spain: Work and family in the age of austerity. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2013, 33, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido, O. Women’s Labour Force Participation in Spain; Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Unidad de Políticas Comparadas (CSIC): Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, B.F.; Escudero, E.B.; Arias, E.E. Desplazamiento y normalización del rechazo laboral hacia las mujeres por cuestiones de talla. Prism. Soc. Rev. Investig. Soc. 2011, 7, 145–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, I. Valores y rasgos estereotípicos de género de mujeres líderes. Psicothema 2004, 16, 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Fiske, S.T.; Lee, T.L. Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassler, S.; Miller, A.J. Waiting to be asked: Gender, power, and relationship progression among cohabiting couples. J. Fam. Issues 2011, 32, 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lifestyle Variables | Total | Medium-Low Conformity | Medium-High Conformity | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 347) | (n = 178) | (n = 169) | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 42.2 (14.0) | 41.0 (14.0) | 43.4 (13.9) | 0.113 a |

| Educational Level | ||||

| Basic Studies (%) | 19.9 | 16.3 | 23.7 | 0.085 b |

| Medium-High Studies (%) | 80.1 | 86.7 | 76.3 | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Alone (%) | 51.3 | 59.0 | 43.2 | 0.003b |

| Not alone (%) | 48.4 | 41.0 | 56.8 | |

| Alcohol Consumption (2 weeks) | ||||

| Yes (%) | 52.7 | 60.1 | 45.0 | 0.005b |

| No (%) | 47.3 | 39.9 | 55.0 | |

| Tobacco Consumption | ||||

| Yes (%) | 19.9 | 24.2 | 15.4 | 0.041b |

| No (%) | 80.1 | 75.8 | 84.6 | |

| Daily sleeping hours (mean, SD) | 7.39 | 7.48 | 7.29 | 0.113 a |

| Social Support (mean, SD) | ||||

| Affective Support | 18.72 (4.4) | 18.81 (4.3) | 18.64 (4.5) | 0.675 a |

| Confidential Support | 23.98 (5.5) | 24.12 (5.2) | 23.84 (5.8) | 0.640 a |

| Total Score | 42.58 (9.5) | 42.81 (9.1) | 42.34 (9.9) | 0.641 a |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| Yes (%) | 67.4 | 68.5 | 66.3 | 0.652 b |

| No (%) | 32.6 | 31.5 | 33.7 |

| Lifestyle Variables | Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Marital Status | 1.89 | 1.23–2.89 | 0.003 | 1.80 | 1.13–2.85 | 0.012 | 1.70 | 1.06–2.71 | 0.025 |

| Alcohol Consumption | 1.84 | 1.20–2.82 | 0.005 | 1.77 | 1.14–2.72 | 0.010 | 1.65 | 1.06–2.56 | 0.026 |

| Tobacco Consumption | 1.75 | 1.02–3.00 | 0.042 | 1.64 | 0.95–2.84 | 0.076 | 1.70 | 0.98–2.96 | 0.059 |

| Physical activity | 0.96 | 0.56–1.65 | 0.888 | 0.92 | 0.53–1.59 | 0.775 | 1.01 | 0.58–1,78 | 0.952 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.113 | ||||||

| Educational level | 0.698 | 0.53–0.91 | 0.010 |

| CFNI Sub-Scales (Mean, SD) | Group 1 (n = 99) | Group 2 (n = 126) | Group 3 (n = 85) | Group 4 (n = 37) | Total (Mean, SD) | p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nice in Relationships | 32.5 (3.1) | 38.0 (5.3) | 38.9 (5.2) | 34.6 (4.8) | 36.3 (5.4) | <0.001 |

| Involvement in Children | 22.7 (3.8) | 22.5 (7.3) | 20.8 (6.6) | 14.1 (6.4) | 21.2 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Thinness | 16.5 (3.4) | 16.8 (6.1) | 19.3 (6.7) | 12.4 (4.2) | 16.9 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Sexual Fidelity | 17.15 (3.3) | 21.2 (5.3) | 14.5 (5.0) | 10.1 (4.4) | 17.2 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Modesty | 13.5 (1.9) | 15.7 (2.9) | 11.3 (3.9) | 11.8 (3.9) | 13.6 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Romantic Relationships | 12.7 (2.2) | 13.5 (3.5) | 15.1 (3.5) | 10.1 (3.0) | 13.3 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Domestic | 16.1 (2.1) | 19.5 (2.9) | 17.8 (3.3) | 13.8 (2.6) | 17.5 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Investment in Appearance | 11.5 (2.0) | 11.3 (3.3) | 14.5 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.7) | 12.0 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Lifestyle Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 99) | (n = 126) | (n = 85) | (n = 37) | (n = 347) | ||

| Age (mean) | 44.25+ | 47.42+ | 35.48− | 34.24− | 42.2 | <0.001a |

| Educational Level | ||||||

| Basic Studies (%) | 26.3+ | 28.6+ | 5.9− | 5.4− | 19.9 | <0.001b |

| Medium-High Studies (%) | 73.7− | 71.4− | 94.1+ | 94.6+ | 80.1 | |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Alone (%) | 42.4− | 38.1− | 74.1+ | 67.6+ | 51.3 | <0.001b |

| Not alone (%) | 57.6+ | 61.9+ | 25.9− | 32.4− | 48.4 | |

| Alcohol Consumption (2 weeks) | ||||||

| Yes (%) | 52.5 | 38.1− | 71.8+ | 49.5− | 52.7 | <0.001b |

| No (%) | 47.5 | 61.9+ | 28.2− | 50.5+ | 47.3 | |

| Tobacco Consumption | ||||||

| Yes (%) | 19.2 | 18.3 | 21.2 | 24.3 | 19.9 | 0.853 b |

| No (%) | 80.8 | 81.7 | 78.8 | 75.7 | 80.1 | |

| Daily sleeping hours (mean) | 7.4 | 7.24 | 7.51 | 7.59 | 7.39 | 0.224 a |

| Social Support (mean) | ||||||

| Affective Support | 18.58 | 18.55 | 18.68 | 19.76 | 18.72 | 0.505 a |

| Confidential Support | 23.73 | 23.47 | 24.25 | 25.81 | 23.98 | 0.135 a |

| Total Score | 42.3 | 41.94 | 42.69 | 45.27 | 42.58 | 0.304 a |

| Physical Activity | ||||||

| Yes (%) | 71.7 | 65.9 | 61.2 | 75.7 | 67.4 | 0.305 a |

| No (%) | 28.3 | 34.1 | 38.8 | 24.3 | 32.6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esteban-Gonzalo, S.; Sik Ying Ho, P.; Aparicio-García, M.E.; Esteban-Gonzalo, L. Understanding the Meaning of Conformity to Feminine Norms in Lifestyle Habits and Health: A Cluster Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041370

Esteban-Gonzalo S, Sik Ying Ho P, Aparicio-García ME, Esteban-Gonzalo L. Understanding the Meaning of Conformity to Feminine Norms in Lifestyle Habits and Health: A Cluster Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(4):1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041370

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsteban-Gonzalo, Sara, Petula Sik Ying Ho, Marta Evelia Aparicio-García, and Laura Esteban-Gonzalo. 2020. "Understanding the Meaning of Conformity to Feminine Norms in Lifestyle Habits and Health: A Cluster Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 4: 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041370

APA StyleEsteban-Gonzalo, S., Sik Ying Ho, P., Aparicio-García, M. E., & Esteban-Gonzalo, L. (2020). Understanding the Meaning of Conformity to Feminine Norms in Lifestyle Habits and Health: A Cluster Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041370