Health Literacy: From a Property of Individuals to One of Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

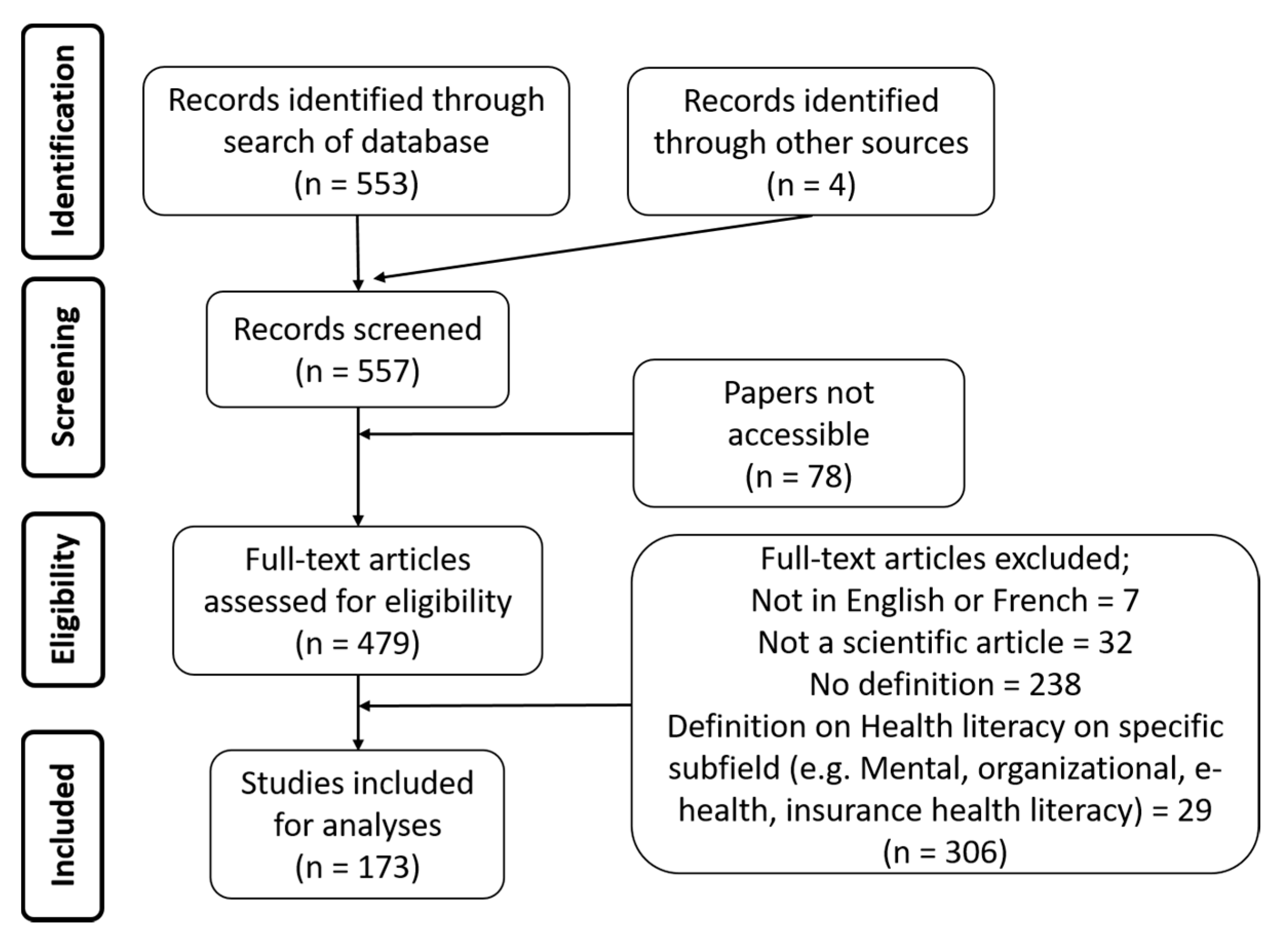

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

“These individual-level health literacy initiatives may do very little to achieve the ultimate goal of promoting equitable health status because “they do not address the root causes of health illiteracy, such as socioeconomic disparities and unequal access to high quality education.”[24] (p. 447)

4. Discussion

4.1. Towards a New Concept for Community Health Literacy

4.2. The Way Forward

Health literacy is linked to literacy and is both a property/quality of a person and of a community. A person’s health literacy entails her/his knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply information on health and upstream determinants of health in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course. When a community is health literate it refers to its capacity to gather information on its upstream SDoH, to mobilize the collective resources to act upon these, to advocate efficiently for structural changes in order to improve the daily living conditions of its members.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s) | Definition |

|---|---|

| WHO (1998) [21] | “Health literacy represents the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health.” |

| American Medical Association (1999) [44] * | “The constellation of skills, including the ability to perform basic reading and numeral tasks required to function in the healthcare environment.” |

| Ratzan and Parker (2000) [22] | “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” |

| Institute of Medicine (2004) [25] * | “The individuals’ capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” |

| Kickbusch, Wait & Maag (2005) [23] | “Health Literacy is the ability to make sound health decisions in the context of everyday life – at home, in the community, at the workplace, in the health care system, the market place and the political arena. It is a critical empowerment strategy to increase people’s control over their health, their ability to seek out information and their ability to take responsibility.” |

| Zarcadoolas et al. (2005) [40] | “The wide range of skills and competencies that people develop over their lifetimes to seek out, comprehend, evaluate, and use health information and concepts to make informed choices, reduce health risks, and increase quality of life.” |

| Paasche-Orlow & Wolf (2006) [45] * | “An individual’s possession of requisite skills for making health-related decisions, which means that health literacy must always be examined in the context of the specific tasks that need to be accomplished. The importance of a contextual appreciation of health literacy must be underscored.” |

| EU (2007) [46] * | “The ability to read, filter and understand health information in order to form sound judgments.” |

| Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008) [47] | “Health literacy is defined as the knowledge and skills required to understand and use information relating to health issues.” |

| Canadian Expert Panel (Rootman and Gordon-El-Bihbety (2008)) [48] | “The ability to access, understand, evaluate and communicate information as a way to promote, maintain and improve health in a variety of settings across the life-course.” |

| Ishikawa & Yano (2008) [49] * | “The knowledge, skills and abilities that pertain to interactions with the healthcare system.” |

| Mancuso (2008) [50] * | “A process that evolves over one’s lifetime and encompasses the attributes of capacity, comprehension, and communication. The attributes of health literacy are integrated within and preceded by the skills, strategies, and abilities embedded within the competencies needed to attain health literacy.” |

| Pavlekovic (2008) * [51] | “The capacity to obtain, interpret and understand basic health information and services and the competence to use such information to enhance health.” |

| Adams et al. (2009) [52] * | “The ability to understand and interpret the meaning of health information in written, spoken or digital form and how this motivates people to embrace or disregard actions relating to health.” |

| Adkins et al. (2009) [53] * | “The ability to derive meaning from different forms of communication by using a variety of skills to accomplish health-related objectives.” |

| Freedman et al. (2009) [24] | “Public health literacy is defined here as the degree to which individuals and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act upon information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community.” |

| Yost et al. (2009) [54] * | “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to read and comprehend health-related print material, identify and interpret information presented in graphical format (charts, graphs and tables), and perform arithmetic operations in order to make appropriate health and care decisions.” |

| Berkman et al. (2010) [55] | “The degree to which individuals can obtain, process, understand, and communicate about health-related information needed to make informed health decisions.’’ |

| Sørensen et al. (2012) [3] | “Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people’s knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course.” |

References

- CSDH. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Health literacy. The solid facts. Health (N.Y.) 2017, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bonaccorsi, G.; Lorini, C.; Baldasseroni, A.; Porchia, B.R.; Capecchi, L. Health services and health literacy: From the rationale to the many facets of a fundamental concept. A literature review. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2016, 52, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Simonds, S.K. Health education as social policy. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, R.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R. Health literacy: Applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodson, S.; Good, S.; Osborne, R. Health Literacy Toolkit for Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Series of Information Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health Systems; World Health Organization: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan, F.M.; Wood, J.E.J.; Fahmy, S.M.; Jones, L.C. Musculoskeletal health disparities: Health literacy, cultural competency, informed consent, and shared decision making. J. Long. Term Eff. Med. Implants 2014, 24, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrenoud, B.; Velonaki, V.-S.; Bodenmann, P.; Ramelet, A.-S. The effectiveness of health literacy interventions on the informed consent process of health care users: A systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2015, 13, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duell, P.; Wright, D.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Bhattacharya, D. Optimal health literacy measurement for the clinical setting: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margat, A.; Gagnayre, R.; Lombrail, P.; de Andrade, V.; Azogui-Levy, S. Health literacy and patient education interventions: A review. Sante Publique Vandoeuvre-Nancy Fr. 2017, 29, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.; Holden, C.A.; Smith, B.J. The correlates of chronic disease-related health literacy and its components among men: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kendir, C.; Kartal, M. Health literacy levels affect breast cancer knowledge and screening attitudes of women in Turkey: A descriptive study. Türkiye Halk Sağlığı Derg. 2019, 17, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Geboers, B.; Brainard, J.S.; Loke, Y.K.; Jansen, C.J.M.; Salter, C.; Reijneveld, S.A.; de Winter, A.F.; deWinter, A.F. The association of health literacy with adherence in older adults, and its role in interventions: A systematic meta-review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 903. [Google Scholar]

- Perazzo, J.; Reyes, D.; Webel, A. A systematic review of health literacy interventions for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, Y.; McGrath, P.J.; Hayden, J.; Kutcher, S. Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wickham, C.A.; Carbone, E.T. What’s technology cooking up? A systematic review of the use of technology in adolescent food literacy programs. Appetite 2018, 125, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G. Health literacy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 2130–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamony, P.; Holt, R.; Barnard, K. The Role of Mobile Applications in Improving Alcohol Health Literacy in Young Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Health Promotion Glossary; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan, S.C.; Parker, R.M. National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy; Selden, C.R., Zorn, M., Ratzan, S.C., Parker, R.M., Eds.; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch, I.; Wait, S.; Maag, D. Navigating Health: The Role of Health Literacy; Alliance for Health and the Future: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, D.A.; Bess, K.D.; Tucker, H.A.; Boyd, D.L.; Tuchman, A.M.; Wallston, K.A. Public health literacy defined. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindig, D.A.; Panzer, A.M.; Nielsen-Bohlman, L. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-309-28332-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D.O. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot. Int. 1998, 1, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, L.M.; Doody, C.; Werner, E.L.; Fullen, B. Self-management skills in chronic disease management: what role does health literacy have? Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.A. Health literacy and adherence to medical treatment in chronic and acute illness: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friis, K.; Lasgaard, M.; Osborne, R.H.; Maindal, H.T. Gaps in understanding health and engagement with healthcare providers across common long-term conditions: A population survey of health literacy in 29 473 Danish citizens. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brabers, A.E.; Rademakers, J.J.; Groenewegen, P.P.; van Dijk, L.; de Jong, J.D. What role does health literacy play in patients’ involvement in medical decision-making? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faruqi, N.; Spooner, C.; Joshi, C.; Lloyd, J.; Dennis, S.; Stocks, N.; Taggart, J.; Harris, M.F. Primary health care-level interventions targeting health literacy and their effect on weight loss: a systematic review. BMC Obes. 2015, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, R.J.; Lou, J.Q.; Ownby, R.L.; Caballero, J. A systematic review of eHealth interventions to improve health literacy. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, T. The Role of Medicine: Dream, Mirage, or Nemesis? Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 56, ISBN 1-4008-5462-8. [Google Scholar]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. Commission on the social determinants of health. In A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D.; McGill, B.; Premkumar, P. Improving health literacy in community populations: A review of progress. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, A.; Batterham, R.W.; Dodson, S.; Astbury, B.; Elsworth, G.R.; McPhee, C.; Jacobson, J.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Systematic development and implementation of interventions to optimise health literacy and access (Ophelia). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowlands, G.; Nutbeam, D. Health literacy and the ‘inverse information law’. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Tehranifar, P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guzys, D.; Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V.; Threlkeld, G. A critical review of population health literacy assessment. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zarcadoolas, C.; Pleasant, A.; Greer, D.S. Understanding health literacy: An expanded model. Health Promot. Int. 2005, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kickbusch, I.S. Health literacy: Addressing the health and education divide. Health Promot. Int. 2001, 16, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, L.; Fenenga, C.; Giammarchi, C.; Di Furia, L.; Hutter, I.; de Winter, A.; Meijering, L. Community-based initiatives improving critical health literacy: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Facilitating Health Communication with Immigrant, Refugee, and Migrant Populations Through the Use of Health Literacy and Community Engagement Strategies: Proceedings of a Workshop; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R.M.; Williams, M.V.; Weiss, B.D.; Baker, D.W.; Davis, T.C.; Doak, C.C.; Doak, L.G.; Hein, K.; Meade, C.D.; Nurss, J.; et al. AMA Health literacy: Report of the council on scientific affairs. J. Am. Med Assoc. 1999, 281, 552–557. [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Together for health: A Strategic Approach for the EU 2008–2013; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. Summary Sesults; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Rootman, I.; Gordon-El-Bihbety, D. A Vision for a Health Literate Canada: Report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy; Canadian Public Health Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, H.; Yano, E. Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect. 2008, 11, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mancuso, J.M. Health literacy: A concept/dimensional analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2008, 10, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlekovic, G. Programmes for Training on Research in Public Health for South Eastern Europe. Health Lit. 2008, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Stocks, N.P.; Hill, C.L.; Gravier, S.; Kickbusch, L.; Beilby, J.J.; Wilson, D.H.; Adams, R.J. Health literacy. A new concept for general practice? Aust. Fam. Physician. 2009, 38, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, N.R.; Corus, C. Health literacy for improved health outcomes: Effective capital in the marketplace. J. Consum. Aff. 2009, 43, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, K.J.; Webster, K.; Baker, D.W.; Choi, S.W.; Bode, R.K.; Hahn, E.A. Bilingual health literacy assessment using the Talking Touchscreen/la Pantalla Parlanchina: Development and pilot testing. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkman, N.D.; Davis, T.C.; McCormack, L. Health literacy: What is it? J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Papers Listed from the Oldest to the Most Recent | Definition/Mention | Locus of Change/Strategies for Change (When Mentioned) | Outcome of Improved Level of HL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutbeam (1998) [21] | “Health literacy represents the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health.” | “knowledge, personal skills and confidence to take action” Through education and empowerment | Change of personal lifestyle and living conditions |

| Ratzan and Parker (2000) [22] | “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” | The capacity of individuals to obtain, process and understand basic health information. Through education | Better reading and understanding medication labels, appointment slips and other health related materials |

| Kickbusch, Wait & Maag (2005) [23] | “Health Literacy is the ability to make sound health decisions in the context of everyday life—at home, in the community, at the workplace, in the health care system, the market place and the political arena. It is a critical empowerment strategy to increase people’s control over their health, their ability to seek out information and their ability to take responsibility.” | Skills to make health-related decisions | Increased skills of an individual on one’s own health. Empowered individuals |

| Freedman et al. (2009) [24] | “Public health literacy is defined here as the degree to which individuals and groups can obtain, process, understand, evaluate, and act upon information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community.” | Power to organize activities to accomplish public health goals and objectives through civic engagement. | Increased skills of individuals/groups to advance the health of communities. |

| Sørensen et al. (2012) [3] | “Health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people’s knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course.” | People’s knowledge, motivation and competences | Maintain and improve the individuals’ quality of life during the life course |

| Locus of Change for HL Enhancement | Outcome of HL Enhancement | SDoH Addressed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL as an individual property | Understand, interpret and critically analyse health information. Make informed decision on health and wellbeing | Improved communication in health, improved health-related behaviours, increased adherence to medications, increased individual participation to health promotion and prevention activities, decreased morbidity and mortality | Proximal factors Individual lifestyle factors, Biological factors, Behaviours |

| HL as a collective property | Knowledge on the broader, upstream determinants of health. Capacity for community mobilisation for change. Capacity for policy advocacy | Change in upstream SDoH, improvement in daily living conditions (housing, social support, urban design, etc.) | Distal factors(that may have a significant impact on proximal ones) Environmental factors, Living conditions |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kendir, C.; Breton, E. Health Literacy: From a Property of Individuals to One of Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051601

Kendir C, Breton E. Health Literacy: From a Property of Individuals to One of Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(5):1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051601

Chicago/Turabian StyleKendir, Candan, and Eric Breton. 2020. "Health Literacy: From a Property of Individuals to One of Communities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 5: 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051601

APA StyleKendir, C., & Breton, E. (2020). Health Literacy: From a Property of Individuals to One of Communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051601