Abstract

Children consume approximately half of their total daily amount of energy at school. Foods consumed are often energy-dense, nutrient-poor. The school food environment represents an effective setting to influence children’s food choices when dietary habits are established and continue to track into adulthood. The aim of this review was to: (1) group methods used for assessing the school food environment according to four food environment dimensions: Physical, economic, socio-cultural and policy and (2) assess the quality of the methods according to four criteria: Comprehensiveness, relevance, generalizability and feasibility. Three databases were searched, and studies were used to assess food and beverages provided at school canteens, tuck shops or cafeterias were included. The review identified 38 global studies (including 49 methods of measuring the food environment). The physical environment was the primary focus for 47% of articles, aspects of policy environment was assessed by 37% articles and a small number of studies assessed the economic (8%) and socio cultural (8%) environment. Three methods were rated ‘high’ quality and seven methods received ‘medium’ quality ratings. The review revealed there are no standardized methods used to measure the school food environment. Robust methods to monitor the school food environment across a range of diverse country contexts is required to provide an understanding of obesogenic school environments.

Keywords:

school food environment; diet; measurement methods; INFORMAS; obesity; canteens; tuck shops; cafeterias 1. Introduction

The International Network for Food and Obesity non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) defines the food environment as the “collective physical, economic, sociocultural and policy surroundings and opportunities and conditions that influence people’s food and beverage choices and nutritional status” [1]. This broad frame-work definition is useful to identify the structural drivers of food acquisition, consumption and nutrient profiles and may encompass a number of measurable key dimensions (availability, accessibility, affordability and desirability of foods) to guide empirical research [2]. Food environment research has gained traction over recent decades in response to the role food environments have played in the global shift away from dietary patterns which included whole grains, fruits, vegetables and legumes to diets comprised of inexpensive, highly palatable and nutrient deplete ultra-processed foods [3]. A number of studies have shown the association between food environments and obesity, dietary patterns, chronic disease and other health related factors [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) [11], the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [12] and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [13] have identified interventions to impact the food environment as strategies for creating population wide improvements in dietary patterns and weight status. The effect of food environments on dietary intake has also increasingly become a policy focus [14,15,16] set against the milieu of the Sustainable Development Goal 2 to end hunger, achieve food and nutrition security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture [17].

National survey data from high income countries show large numbers of children consume inadequate amounts of fruits and vegetables that fall well below recommended guidelines [18,19,20]. A recent Australian study, of 3496 school children showed that only 15% of males and 18.5% of female school children, reported consuming enough vegetables to meet the dietary guidelines [21]. Worldwide studies have also revealed that children consumed almost 40% of their daily recommended energy intake from energy-dense nutrient-poor foods (EDNP) [22,23].

The school food environment as defined by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) “refers to all the spaces, infrastructure and conditions inside and around the school premises where food is available, obtained, purchased and/or consumed (for example tuck shops, kiosks, canteens, food vendors, vending machines” [24]. It represents an effective setting for interventions to influence children’s food choices at a time when dietary habits are developed and continue to follow an established trajectory across the lifespan [25,26]. Children consume on average, 40% of total amount of energy during the school hours [27] and often the types of foods consumed are high in saturated fat, added sugar and salt (e.g., waffles, chocolate milk, iced teas, cakes and sausages) [28]. The provision of these types of foods and beverages at these settings undermine dietary guidelines and encourage the notion that these types of foods may be consumed everyday rather than occasionally [29]. School canteens/tuck shops/cafeterias, which are often the sources of these types of foods, are also highly visible and accessible and thus play an important role in modelling a healthy food environment and establishing healthy eating behaviors early in life [22,27,30]. Furthermore, despite school canteen’s being an optimal intervention target, there is existing evidence that their adherence to government healthy nutrition policy is not always ideal [31].

The school food environment varies internationally with countries including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa providing food and beverages for purchase via canteens or tuck shops and others including the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States providing meals via school lunch programs [22,32]. This heterogeneity and complexity of the school food environment presents a challenge in determining a best practice, standardized measurement tool to assess the school food environment.

High quality measurement methods are required to conduct assessments and evaluations of the school food environment to inform future policies and practices that will lead to improved quality of life, improvements in healthy weight and associated direct and indirect health care costs. Categorization of the methods used to measure the school food environment according to the conceptualized four dimensions of the food environment (i) physical (availability); (ii) economic (cost); (iii) socio-cultural (attitudes, perceptions) and (iv) policy (the rules) [33] may inform the choice and harmonization of the assessment methods and facilitate a greater understanding of obesity promoting school environments.

In this context and to further the work in this area we undertook a study to: (1) classify the measurement methods according to the four dimensions of the food environment and (2) review and assess the quality of the measurement methods used to assess the school food environment

2. Methods

This review followed the systematic steps outlined in the PRISMA guidelines [34] and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number CRD42019125063).

2.1. Search Methods to Identify Studies

We conducted an electronic search in January 2019 of peer reviewed literature using: Medline, Embase and Web of Science. Recent cross-sectional studies conducted globally formed the basis for this review. Search terms were adapted to databases according to three main topic areas of (1) school food environments; (2) measurement methods and (3) tuck shop or canteen, café or cafeteria. For this review, the school could either be a primary/elementary school, secondary/senior school or after school care.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following search criteria were used in this review: (i) studies published in English in peer reviewed studies, (ii) human studies, (iii) studies from any country and (iv) studies which specified the methods or tools used to assess food and/or beverage items provided at school canteens, tuck shops or cafeterias. Studies included in this review included both qualitative and quantitative methods.

Reviews, conducted in settings other than schools (e.g., kindergartens), focused on individual dietary intakes or nutritional status of children, assessed foods provided from vending machines or food wastage or primarily utilized dietary assessment methods (e.g., 24-h recall or food frequency questionnaires) were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction and Analysis

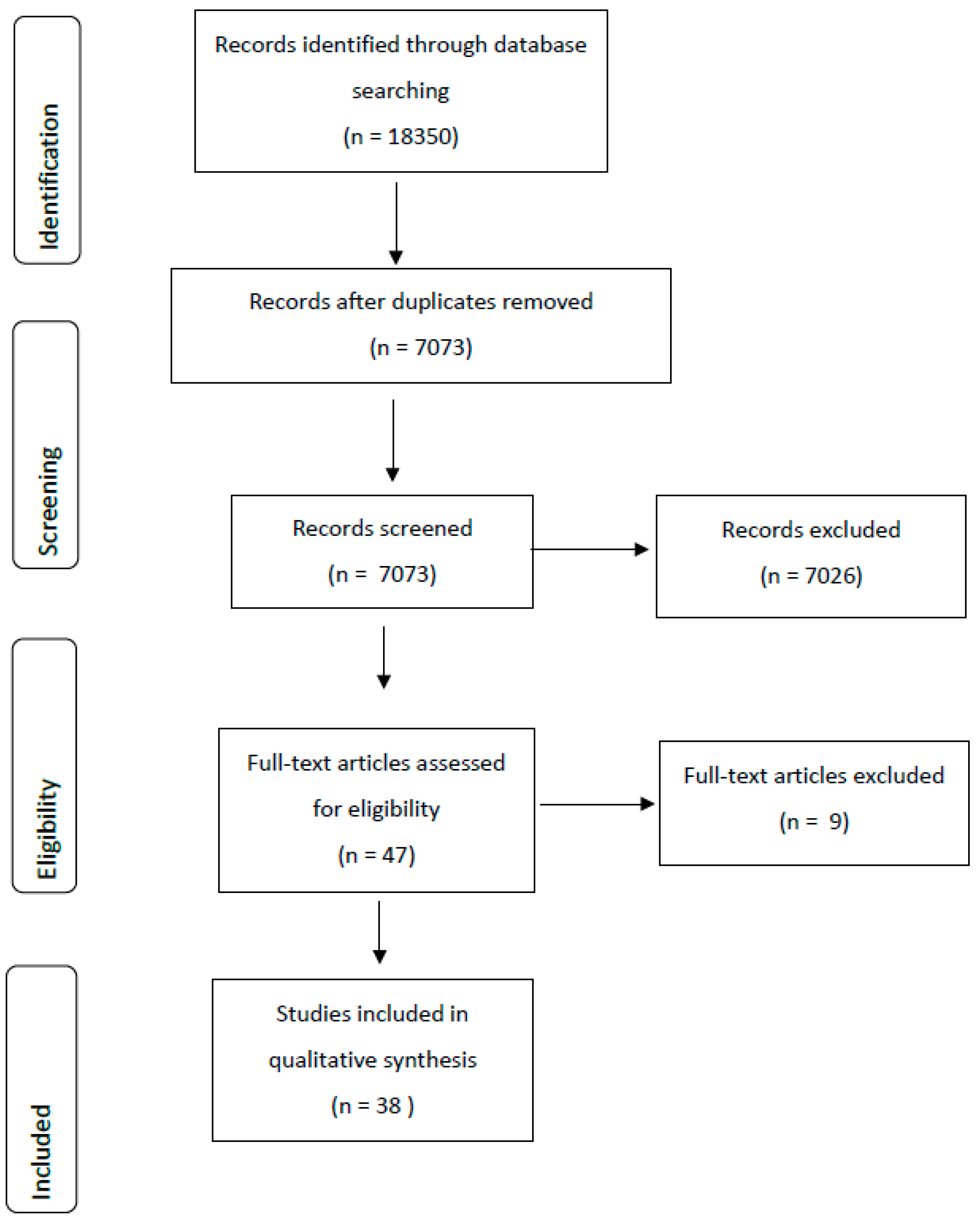

The lead researcher (SO’H) reviewed all results from all three databases, removed duplicates and screened all results based on titles and abstracts against the review criteria (Figure 1). Reference lists of included articles were searched for additional relevant studies. When the abstract was considered insufficient to make conclusions about inclusion the full text was screened.

Figure 1.

Summary of the literature search process.

Data were extracted into a detailed data spreadsheet from the full text independently by the two researchers (SO’H and GE). Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer if necessary.

2.4. Quality Assessment of Methods

This study used an adapted version of a quality assessment tool that included criteria which was developed by INFORMAS researchers from public health and political science literature [1]. To provide an overall assessment of the quality of methods, the following four criteria were considered most relevant to critically assess the quality of the methods [35] used for measuring food provision in this context: Comprehensiveness, relevance, generalizability and feasibility.

Methods were assessed against these criteria and the results combined to form an overall quality rating for each method (refer to Supplementary Materials Figure S1 for more details of criteria and standards for quality assessment of methods used). Two independent reviewers (SO’H and MK) in a two-step process completed the quality assessment: The first reviewer assessed the quality of all studies; the second reviewer assessed the quality of a 10% random sample of the reviewed studies. A study sample size of 10% has been used previously for random sampling in a number of other studies [35]. The two reviewers were in consensus on the quality of all papers in the 10% sample.

2.5. Dimensions of the Food Environment Framework

In this study, we have used the four environmental dimensions (physical, economic, sociocultural and policy) as defined by Swinburn et al. [33] to categorize the methods used to measure the school food environment e.g., semi-structured interviews with food service providers regarding school nutrition guidelines was categorized as ‘policy’ food environment. (Table 1).

Table 1.

The four environmental dimensions used to group the food environment measurement methods (adapted from Swinburn et al. [33]).

3. Results

The extensive search yielded 18,350 relevant abstracts, with a total of 38 articles meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Major reasons for exclusion at full text stage was that the study did not explicitly describe the measurement method used to measure the food environment. An overview of key study characteristics is provided (Table 2). Articles were published from 2003 to 2018 and included data collected between 1993 and 2016.

Table 2.

Summary of identified studies measuring the school food environment.

3.1. Where has Food Environment Research been Undertaken?

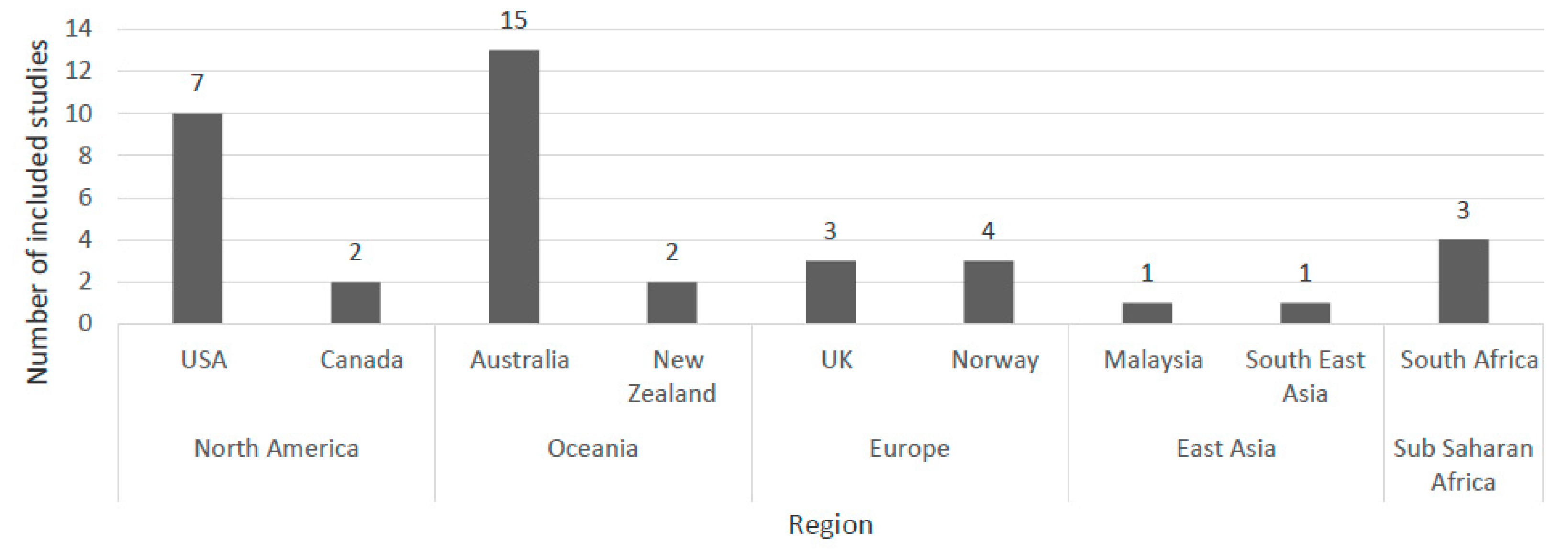

Of the 38 studies included, one study featured multiple countries including Northern/Central, Southern and Eastern-European countries [36] and 37 studies were single-country [22,28,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Thirty-three studies were conducted in high-income countries (87%) and five located in low and middle-income countries (13%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study characteristics of the articles identified in the review.

3.2. Quantitative Methods

Thirty-one articles sought to characterize the school food environments using quantitative methods. Amongst these articles the vast majority featured one measurement method including menu analysis (n = 5), direct observation (n = 3), self-completed questionnaire (n = 11) and surveys (n = 8). Four articles (15%) featured two approaches including surveys and canteen menu audits [65] or observations [60] menu analysis and telephone interviews [22] and self-reported survey and menu audits [66].

3.3. Qualitative Methods

Of the 38 articles, two articles used qualitative stakeholder-based methods to describe the school food environment [46,57]. Drummond and Sheppard utilized focus groups interviews with Australian school students and semi-structured interviews with principals, parents, teachers and canteen managers. The interviews explored participant’s perceptions around healthy eating, likes/dislikes about the canteen, policy implementation and canteen profit expectations were probed [46]. The article by Masse et al., featured a single method, where Canadian principals and teacher/school informants participated in semi-structured interviews exploring their perceptions of the implementation of national guidelines within the school environment [57].

3.4. Mixed Method and Mixture of Methods

Five articles included a mixed methods approach where quantitative data was integrated with qualitative data, to provide comprehensive insight into the school food environment [28,37,39,40,42] and one study conducted a mixture of methods study [64]. Bevans and colleagues [39] and Ardzejewska et al. [37] used semi-structured interviews with food service managers/school principals/deputies where their school’s nutrition service policies and practices were explored, together with either student questionnaires [40] or canteen menu audits [37].

Two articles which featured focus groups, explored concepts around healthy eating with students from South Africa [39], and in the UK student discussions centered on four key themes: Children’s food environment, food intake, obtaining food and social aspects of food consumption [42]. South African learners also completed a self-administered questionnaire which examined tuck shop purchasing behavior whereas the school food environment was assessed by a lunch time observation and menu analysis in the UK [42].

Chortatos et al. [28] conducted student focus group discussions which explored themes such as eating habits, definitions of healthy and unhealthy foods and attitudes towards diet. Interviews around food availability and meals served at school were conducted with school administrators and a student web-based questionnaire included questions about school canteens and food and drink consumption [28].

Pettigrew et al. [64] conducted a mixture of methods study which included semi-structured focus groups discussions with parents around school food policy and school-based stakeholder (principals, teachers and canteen managers) interviews, which included knowledge and attitudes around canteen policy and factors influencing compliance with the policy. In the quantitative phase of the study, the parents and principals responded to a telephone questionnaire [64].

3.5. The Food Environment Dimensions, Quality Assessment and Advantages and Disadvantages

Table 2 provides study details including key features, advantages and disadvantages of the methods used to assess the school food environment, the food environment dimensions and the overall quality rating of the method. Only three studies received a ‘high’ quality rating [37,43,53]. These were studies conducted in high income countries (e.g., Norway and New Zealand) and included all four dimensions of the school food environment. Seven studies were rated as ‘medium’ quality [22,28,38,46,60,65,71] and twenty-nine studies were rated as ‘low’ quality [37,39,40,41,42,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70]. The number of methods which were assessed was 49, as a number of studies applied more than one methodological approach to measure to school food environment.

3.5.1. Physical Environment

The physical food environment was the primary focus for eighteen articles (47%) included in this review [38,39,42,45,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,59,62,63,67,68,69]. It was operationalized in terms of either availability of food items frequently for sale or the physical presence of a school food outlet. Three studies conducted onsite inspections of school canteens to determine either the types of ‘competitive’ foods (e.g., foods high in salt, sugar and saturated fat) sold [67] or the frequency of food and drinks from different food groups sold according to days/week [63] or the availability of foods items in à la carte restaurants [52]. Student surveys were used to determine the frequency of use of à la carte cafeterias [62] and tuck shops [59] and a self-administered tuck shop checklist was completed by teachers in a study by Ma and Wong [56]. Two studies determined the presence of a canteen/booth/school store either via a school principal questionnaire [53] or by onsite observation by research staff [50]. In the study by Gebremariam et al. students were asked about the frequency of daily canteen purchases [54]. Finch and colleagues surveyed schools to determine frequency of canteen purchases [48] and Faber et al. determined what food items were available from the school tuck shop in poorly resourced South African schools, via questionnaires and observations [47].

3.5.2. Economic Environment

A small number of studies (n = 3) measured the economic environment which involved obtaining the price of foods available in school canteens either via extracting price data from online canteen menus (items available for purchase were snacks e.g., crisps, fruit and lunch e.g., sandwich, pizza snack) [41,71] or by obtaining canteen sales data from food service staff at participating schools [43]. Two studies utilized the data from the online menus, to conduct price analysis to determine if there were significant differences between the mean price of healthy and unhealthy products [41,71]. Carter and Swinburn described the cost of healthy and unhealthy foods sold in schools and determined if the canteen was run for profit, not-for-profit or contracted it out as a private business [41]. The authors also determined if schools used food sales for fundraising [43]. All three studies demonstrated that the pricing of foods sold in school canteens favored less nutritious foods compared to nutritious alternatives which provided some insight into the school economic food environment [41,43,71].

3.5.3. Socio-Cultural Environment

Three studies measured aspects related to the school’s socio-cultural environment [41,47,53]. As part of a principal questionnaire, Gebremariam et al. assessed the perceived responsibility of the school for the diet of Norwegian students and the degree of priority given to food and nutrition beyond what was mandatory via a statement with a five-response category [53]. Faber and colleagues asked South African educators via a self-administered questionnaire about their interest and training received in nutrition, if nutrition was included in classroom teaching and their perceived role in nutrition education and healthy eating promotion [47]. In New Zealand, Carter and Swinburn developed a questionnaire using information from semi-structured interviews with primary schools and asked schools to rate three statements to indicate how they applied to their school: If nutrition was a priority, if healthy food provision was supported by management and if foods provided at school were highly nutritious [43].

3.5.4. Policy Environment

The literature search yielded fourteen (37%) studies, which assessed aspects of the policy environment [70]. Most studies investigated if the school had a food policy either in combination with assessing the physical environment (e.g., the availability of food and drink) the socio-cultural environment (responsibility of the schools for children’s diets) or the economic environment. Only one study solely assessed the policy environment via principal interviews [37]. Twelve studies (29%) approached the school principal about their school food policy, one study questioned teachers [43], two canteen managers [65,66] and one examined online school menus to determine if food items available for purchase in canteens were compliant with guidelines [70]. Three studies determined if the school food policy was compliant with a government-mandated policy [28,65,70].

4. Discussion

This is the first review to comprehensively report on the methods used to measure the school food environment. The review identified 38 relevant studies which we categorized according to the conceptualized four dimensions of the food environment. The quality of the methods varied widely with only three methods [36,43,53] rated as high quality according to the detailed assessment criteria (Table 2) and included all four dimensions of the food environment. Studies that included food environment assessment methods that rated as high quality included a school management questionnaire of the food environment (guided by the existing Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO) framework [33]), school environment assessments and the collection of food sales data from school food outlets.

The most common method used to measure the school food environment was a self-administered questionnaire/survey (n = 21) [28,36,39,40,42,43,44,45,47,48,51,52,53,54,56,58,59,62,64,66,68] to obtain information such as food policy, food purchased or availability from tuck shops or school meals, presence of a tuck shop, if nutrition training was a priority or attitudes to nutrition from either school principals, students, educators or canteen managers. Disadvantages with this method include self-reported bias in favor of desirable rather than actual practice, a low response rate which may not be indicative of true food provision and respondent burden. Likewise, survey results may not capture realistic practices e.g., food policy as an indicator of the policy environment does not assess the level of effectiveness of a policy [43]. Advantages are the low cost, ease of administration, access to a large number of participants and the reporting of other nutrition practices that may be otherwise overlooked by just reviewing menus.

Six of our included studies utilized observational data collection methods where trained researchers observed food provision in the canteens/tuck shops or school restaurants [37,38,47,60,65,67]. This data collection method can be highly variable and can subsequently provide inaccurate reflections of food provision and poor generalizability of findings [72]. However, direct observation methods may improve the validity of self-administered surveys and on-site/direct observations are considered the ideal approach in assessing school environmental characteristics [60] and nutrition practices [32].

Canteen menu analysis was utilized by six studies, which involved either obtaining a school menu online or from canteen managers [22,55,61,65,70,71]. Although menu review is an objective measure, it may not be a reliable tool for food provision assessment, as the actual food available may differ from the planned menu and insufficient information may limit the account of portion sizes, types of foods, or pricing [64]. Skilled researchers (e.g., dietitians) in menu coding and analysis are also often required to conduct the research and often menus are only assessed at one point in time, so the certainty of the menus being offered at all times, over the school year is unknown. However, compared to on-site observations, menu reviews are lower in implementation costs and less labor-intensive [64]

Seven studies included semi-structured interviews with school principals or canteen/food service manager [41,46,50,57,60,64,69] and/or focus groups with students [46,64]. This subjective measurement method is expensive due to the labor required to conduct the research. However, rich data can be obtained, and other food provision practices may be captured that may be otherwise missed by observational methods.

Of note, only small number of studies (n = 7) included validity and/or reliability tests for the methods used to measure the school food environment, the details of which are included in Table 2.

Of the four conceptualized dimensions, the physical food environment was the most common dimension investigated. A medium to low quality assessment rating was applied to most studies due to utilization of only one measurement method (e.g., the availability of food items for sale). Inclusion of more than method to measure the physical food environment (e.g., indication of the physical presence of a purpose built canteen, the availability of food for sale and the frequency of sale) would have gained an optimal quality rating. A shared theme across most studies was the availability of cheap, convenient foods high in saturated fat, salt and sugar available at school canteens/tuck shops. There is considerable scope to improve the availability of healthy choices, within schools in view of reducing the risk of childhood overweight and obesity. Indeed, limiting or decreasing the availability of unhealthy foods has been found to be associated with less frequent purchases of these items in school [62]. Other study findings relate to the physical presence of school canteens with one study noting that the presence of school canteens did not seem to influence children’s intake, although the authors did note that these findings may be attributable to the infrequency in canteen opening times (most were only open once/week) [53]. Another reported that whilst most schools had a canteen food service, many had inadequate canteen facilities, with only 15% of schools having purpose-built facilities [43]. The lack of canteen amenities limits the capacity to provide freshly prepared foods and encourages the sale of prepackaged products such as pies and other savory pastries [43].

Regarding the economic environment, one study found that schools operated their food service for profit and used food products (pizzas and pies) as fundraising initiatives [43], suggesting that school profitability was placed above student health as a priority. It is also worth noting that only three studies investigated the cost of healthy versus unhealthy foods and showed that the mean price of healthy lunch items (e.g., salad sandwich) was greater than the less healthy item (e.g., meat pie) [41,43,71] which suggests there is an opportunity to introduce pricing strategies to make healthier choices the easiest options for children. Price is seldom considered in healthy school food policies, yet studies have shown that improving youth’s financial access to healthy foods may reduce the risk of obesity, particularly amongst those from a lower socio-economic position [73]. Price is also a strong predictor of consumer’s choice of food and beverages and given that schools have a duty to create a healthy school food environment [74] further investigation of pricing strategies of school canteens/tuck shops could be a focus for future research, particularly in lower-income schools which are reported as having less healthy food environments than in high-come schools [75]. In terms of limitations of the findings, all three included studies utilized descriptive analysis. Thus, the examination of the associations between student purchases and the price of school canteen food would provide a more comprehensive picture of the economic food environment. Inclusion of price changes over time, the effect of seasonal discounts and interactions between price and promotion/or placement of canteen foods would improve the quality of the methods used to measure the economic food environment.

Only three studies included in our review solely investigated the socio-cultural environment [43,47,53]. Based on the quality assessment, measuring the socio-cultural environment via questionnaires regarding attitudes to nutrition was limited by respondent bias. Collectively, schools had positive attitudes to nutrition, acknowledged a responsibility for children’s diets and agreed that health and nutrition should be prioritized and promoted by the school. It is unclear whether these findings translate into successfully influencing children’s healthy eating knowledge and improved eating habits and thus warrants further research. Of note, one study reported that schools did not consider the school environment as playing a part in nutritional outcomes which may be because educators believe they have limited influence on altering the food service [43]. It is important that the attitudes and beliefs of school food providers, which can be seen as potential barriers to the implementation of school food policies [66], should not be overlooked when analyzing the environmental factors influencing obesity and ought to be used to guide implementation support strategies [34].

The policy environment was a dimension that was explored by a number of articles included in our review which probed the existence of a school food policy governing food availability or if the foods choices available in school canteens were compliant with government mandated policies and guidelines. A common finding across our studies revealed that nutrition policies are poorly implemented at the school level, limiting their public health impact [22,55,70].

The WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health has called for “governments to adopt policies that support healthy diets at schools and to limit the availability of products high in salt, sugar and fats” [76]. In addition, the development of nutrition standards for all foods sold or provided at schools has been recommended by a number of agencies including the WHO [77], the Center for Disease Control and Prevention [13], the IOM [12] and the WHO EU [77]. In keeping with these recommendations, the WHO developed the Nutrition Friendly Schools Initiative, where schools which meet a set of criteria will be recognized as “Nutrition Friendly Schools”. Although the initiative does not provide specific standards related to the nutritional quality of foods provided and sold, it is a whole-of-school approach that calls for healthy diet and eating practices [78]. Policies have also been introduced in the school setting in a number of countries that support the provision of food aligned with national dietary guidelines. For example, all Australian states and territories have introduced voluntary healthy canteen policies that promote the sale of healthy foods and restrict the sale of less healthy foods [70]. Likewise, in the UK the mandated ‘School Food Plan’ is a set of standards that compels schools to provide children access to nutritious meals at schools [79]. However, international research suggests that most schools fail to implement school nutrition policies [80,81] and on their own, they are insufficient to guarantee the provision of healthy foods in schools. To ensure policies are appropriately implemented to achieve the desired outcomes, to contribute to accountability measures to stakeholders and to provide a basis for future actions, comprehensive monitoring of adherence to school food policy standards is required.

4.1. Future Practice

The International Network for Food and Obesity non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) is a global network of researchers that aims to monitor benchmark and support public and private sector actions to create healthy food environments and reduce obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [1]. The network aims to do this by developing a global framework for monitoring foods and beverages provided or sold in schools that can be used to compare and evaluate the nutritional quality of the foods, compared with specific policies within and across jurisdictions. The framework is composed of nine impact modules one of which ‘food provision (in schools)’, where information about nutrition policies in countries and school nutrition policies and standards/guidelines are collected in two components. These monitoring practices facilitate accountability measures and provide a basis for the development of new or improved standards. In addition, nutrition policy programs are also important for other areas of research such as local food environments surrounding schools [82,83] and associated environmental impacts and economic development [84].

Assessing adherence to nutrition standards in some countries will still be a challenge as policies/guidelines differ in the way they have been developed (voluntarily or mandatory) and implemented at different government levels (e.g., national, state/provincial or local) [32]. Guidelines may differ in the way they are applied e.g., just to meals/foods served or available for purchase or the whole school food environment to include fundraising and sponsorship [33]. Monitoring therefore may also be difficult in some countries or states where food is not centrally provided by schools or in low to middle income countries which may not have the financial capacity to monitor nutrition programs. Even so, a major advantage of applying the INFORMAS framework is the use of a standardized method to measure the school food environment in different contexts which will allow for comparisons across different countries, settings and times. There is also the potential for effective benchmarking of performance, which can assist in contributing to increasing accountability of schools and their actions to improve the healthiness of the foods provided. Some progress within the ‘school provision’ module has been made, with an online tool called the School Food Environment Review and Support Tool (School-Ferst), available on the INFORMAS site, which is designed to support schools to assess the healthiness of the foods and beverages provided (available online: https://www.informas.org/modules/food-provision/).

Another measurement tool not identified in the studies included in this review, which could be applied to the school food environment, is the Food Store Environment Examination (FoodSee) methodology, which quantifies participant’s interaction with the food store environment [85]. Participants wear a camera and global positioning system (GPS) unit on a lanyard, which captures 136-degree image of the scene ahead approximately every seven seconds, enabling accurate and rapid speed mapping of the surrounding food environment in the participant’s location [85]. This new tool has been utilized in a feasibility study, which focused on images from food outlets captured by children aged 11–13 years and evaluated the possibility of assessing food availability and marketing [85]. This method requires further validation but shows promise of being a high-quality methodology to measure surrounding food environments, particularly the availability of food. For studies involving children, this tool could be utilized to objectively and unobtrusively measure children’s interaction with school canteens/tuck shops and could enable a number of the four dimensions of the food environment to be assessed e.g., food product availability, placement, price promotion and purchases.

In addition, it important to note, that our review revealed only 38 global studies which assessed the school food environment with dominance in high income countries (e.g., USA, Australia). Thus, if the World Health Organization, INFORMAS and/or government organizations are to make substantial gains in improving the school food environment globally, then there is a need for further research into appropriate measurement methods which are high quality and can be applied broadly across a range of country contexts.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

There are a number of strengths to this review. A comprehensive search strategy of literature, using robust review methods was undertaken to identify methods used to measure the school food environment. The study rated the quality of each method and the quality assessment criteria could be applied elsewhere. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the search was restricted to English language publications, which may have resulted in the exclusion of important non-English publications. Studies utilizing methods to measure the school food environment were mostly from high-income countries rather than low and middle income countries. This may have been due to the literature search being limited to peer reviewed studies in English only and as such relevant publications in languages other than English may have been missed. In addition, studies were conducted in different contexts making comparisons challenging.

5. Conclusions

Grouping the measurements methods according to the four dimensions of the school food environment provided insight into which dimensions were most commonly explored and those elements that may warrant further research in the future. Our review also revealed that there are no common standard methods used to measure the school food environment across different country contexts. This was due to the diverse methodological approaches used to measure the school food environment and the differing jurisdictions where foods are provided to children as part of a school lunch program (e.g., the UK) or where foods are available for purchase at school canteens or tuck shops (e.g., Australia). The lack of standardized measurement methods identified in this review is broadly consistent with previous systematic reviews from high income [4,10,86,87,88] and low–middle income countries [89] and with a review which quantified the methods used to measure the ‘retail food environment’ and associations with obesity [90]. The field therefore is in need of standardized methods and indicators to profile and monitor the school food environment across the diverse high and low to middle income settings and to provide robust assessments of the influence of the school food environment on nutrition and health.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/5/1623/s1, Figure S1: Criteria and standards for quality assessment of the school food environment measurement methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O.; methodology, S.O., M.G. and L.A.; formal analysis, S.O. and G.E.; writing—original draft preparation S.O.; writing, review and editing, S.O., G.E., M.G. and L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.; et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Ahmed, S. The food environment, its effect on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, C.E.; Sorensen, G.; Subramanian, S.V.; Kawachi, I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place 2012, 18, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Glass, T.A.; Curriero, F.C.; Stewart, W.F.; Schwartz, B.S. The built environment and obesity: A systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place 2010, 16, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; Flood, V.M.; Yeatman, H. Measuring local food environments: An overview of available methods and measures. Health Place 2011, 17, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Reedy, J.; Butler, E.N.; Dodd, K.W.; Subar, A.F.; Thompson, F.E. McKinnon, R.A. Dietary assessment in food environment research: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Johnson, L.; Yaroch, A.L.; Phillips, M.; Ayala, G.X.; Davis, E.L. Measures of Retail Food Store Environments and Sales: Review and Implications for Healthy Eating Initiatives. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Engler-Stringer, R.; Le, H.; Gerrard, A.; Muhajarine, N. The community and consumer food environment and children’s diet: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Dominick, C.; Devi, A.; Swinburn, B. The healthy food environment policy index: Findings of an expert panel in New Zealand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance; Institute of Medicine Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Youth K.J. LC, Kraak VI, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving the Food Environment Through Nutrition Standards: A Guide for Government Procurement; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011.

- Development Initiatives. Global Nutrition Report 2017: Nourishing the SDGs; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2017.

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. Nutrition and Food Systems; A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security; Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bradlee, M.L.; Singer, M.R.; Qureshi, M.M.; Moore, L.L. Food group intake and central obesity among children and adolescents in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Moore, L.V.; Galuska, D.; Wright, A.P.; Harris, D.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Merlo, C.L.; Nihiser, A.J.; Rhodes, D.G. Vital signs: Fruit and vegetable intake among children—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2014, 63, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lynch, C.; Kristjansdottir, A.G.; Te Velde, S.J.; Lien, N.; Roos, E.; Thorsdottir, I.; Krawinkel, M.; de Almeida, M.D.V.; Papadaki, A.; Ribic, C.H.; et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries—The PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2436–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alston, L.; Crooks, N.; Strugnell, C.; Orellana, L.; Allender, S.; Rennie, C.; Nichols, M. Associations between School Food Environments, Body Mass Index and Dietary Intakes among Regional School Students in Victoria, Australia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoong, S.L.; Nathan, N.K.; Wyse, R.J.; Preece, S.J.; Williams, C.M.; Sutherland, R.L.; Wiggers, J.H.; Delaney, T.M.; Wolfenden, L. Assessment of the School Nutrition Environment: A Study in Australian Primary School Canteens. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; de Ridder, K.; Fiolet, T.; Bel, S.; Tafforeau, J. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and diet quality among children, adolescents and adults in Belgium. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 58, 3267–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. School Food and Nutrition. Healthy food Environment and School Food. Available online: http://www.fao.org/school-food/areas-work/food-environment/en/ (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; French, S. The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child. 2006, 16, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.C.; Swinburn, B.A. What are the key food groups to target for preventing obesity and improving nutrition in schools? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chortatos, A.; Terragni, L.; Henjum, S.; Gjertsen, M.; Torheim, L.E.; Gebremariam, K. Consumption habits of school canteen and non-canteen users among Norwegian young adolescents: A mixed method analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.C.; Swinburn, B.A. School canteens: Using ripples to create a wave of healthy eating. Med. J. Aust. 2005, 183, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanigorski, A.M.; Bell, A.C.; Kremer, P.J.; Swinburn, B.A. Lunchbox contents of Australian school children: Room for improvement. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Silva-Sanigorski, A.; Breheny, T.; Jones, L.; Lacy, K.; Kremer, P.; Carpenter, L.; Bolton, K.; Prosser, L.; Gibbs, L.; Waters, E.; et al. Government food service policies and guidelines do not create healthy school canteens. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2011, 35, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Abbe, M.; Schermel, A.; Minaker, L.; Kelly, B.; Lee, A.; Vandevijvere, S.; Twohig, P.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; et al. Monitoring foods and beverages provided and sold in public sector settings. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.; Egger, G.; Raza, F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: The development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev. Med. 1999, 29, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phulkerd, S.; Lawrence, M.; Vandevijvere, S.; Sacks, G.; Worsley, A.; Tangcharoensathien, V. A review of methods and tools to assess the implementation of government policies to create healthy food environments for preventing obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases. Implement Sci. 2016, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, N.; van Stralen, M.M.; Androutsos, O.; Bere, E.; Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Jan, N.; Kovacs, E.; van Lippevelde, W.; Manios, Y.; Te Velde, S.J.; et al. The school nutrition environment and its association with soft drink intakes in seven countries across Europe—The ENERGY project. Health Place 2014, 30, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardzejewska, K.; Tadros, R.; Baxter, D. A descriptive study on the barriers and facilitators to implementation of the NSW (Australia) Healthy School Canteen Strategy. Health Educ. J. 2012, 72, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beets, M.W.; Weaver, R.G.; Turner-McGrievy., G.; Beighle., A.; Moore., J.B.; Webster, C.; Khan, M.; Saunders, R. Compliance with the Healthy Eating Standards in YMCA After-School Programs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 555–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, F.; Marais, M.; Koenm, N. The provision of healthy food in a school tuck shop: Does it influence primary-school students’ perceptions, attitudes and behaviours towards healthy eating? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevans, K.B.; Sanchez, B.; Teneralli, R.; Forrest, C.B. Children’s eating behaviour: The importance of nutrition standards for foods in schools. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billich, N.; Adderley, M.; Ford, L.; Keeton, I.; Palermo, C.; Peeters, A.; Woods, J.; Backholer, K. The relative price of healthy and less healthy foods available in Australian school canteens. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 1, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, L.; Lake, A.A. Exploring school and home food environments: Perceptions of 8-10-year-olds and their parents in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, M.A.; Swinburn, B. Measuring the ‘obesogenic’ food environment in New Zealand primary schools. Health Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, V.; Worsley, A.; Crawford, D. What are 5 and 6 children buying from school canteens and what do parents and teachers think about it? Nutr. Diet. 2004, 61, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, E.M.; Crepinsek, M.K.; Fox, M.K. School meals: Types of foods offered to and consumed by children at lunch and breakfast. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, S67–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, C.; Sheppard, L. Examining primary and secondary school canteens and their place within the school system: A South Australian study. Health Educ. Res. 2011, 26, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, M.; Laurie, S.; Maduna, M.; Magudulela, T.; Muehlhoff, E. Is the school food environment conducive to healthy eating in poorly resourced South African schools? Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, M.; Sutherland, R.; Harrison, M.; Collins, C. Canteen purchasing practices of year 1-6 primary school children and association with SES and weight status. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2006, 30, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, M.; Begley, A.; Sutherland, R.; Harrison, M.; Collins, C. Development and reproducibility of a tool to assess school food-purchasing practices and lifestyle habits of Australian primary school-aged children. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 64, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.K.; Dodd, A.H.; Wilson, A.; Gleason, P.M. Association between school food environment and practices and body mass index of US public school children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, S108–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Story, M.; Fulkerson, J.A. School food policies and practices: A state-wide survey of secondary school principals. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1785–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Story, M.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Gerlach, A.F. Food environment in secondary schools: A la carte, vending machines, and food policies and practices. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Andersen, L.F.; Bjelland, M.; Klepp, K.I.; Totland, T.H.; Bergh, I.H.; Lien, N. Does the school food environment influence the dietary behaviours of Norwegian 11-year-olds? The HEIA study. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Henjum, S.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L.E. Correlates of fruit, vegetable, soft drink, and snack intake among adolescents: The ESSENS study. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, A.; Nathan, N.; Robinson, K.; Fox, D.; Wolfenden, L. Improvement in primary school adherence to the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy in 2007 and 2010. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2015, 26, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, A.W.; Wong, M.C. Secondary school tuck shop options and student choices: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse, L.C.; Naiman, D.; Naylor, P.J. From policy to practice: Implementation of physical activity and food policies in schools. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 3, 10–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masse, L.C.; de Niet-Fitzgerald, J.E.; Watts, A.W.; Naylor, P.J.; Saewyc, E.M. Associations between the school food environment, student consumption and body mass index of Canadian adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Tapper, K. The impact of school fruit tuck shops and school food policies on children’s fruit consumption: A cluster randomised trial of schools in deprived areas. J. Epidemiol. Commun. H. 2008, 62, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, N.; Wolfenden, L.; Morgan, P.J.; Bell, A.C.; Barker, D.; Wiggers, J. Validity of a self-report survey tool measuring the nutrition and physical activity environment of primary schools. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, N.; Yoong, S.L.; Sutherland, R.; Reilly, K.; Delaney, T.; Janssen, L.; Robertson, K.; Reynolds, R.; Chai, L.K.; Lecathelinais, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to enhance implementation of a healthy canteen policy in Australian primary schools: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; French, S.A.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Fulkerson, J.A. School lunch and snacking patterns among high school students: Associations with school food environment and policies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2005, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, J.; Wood, L.; Harper, C.; Nelson, M. The impact of the food-based and nutrient-based standards on lunchtime food and drink provision and consumption in secondary schools in England. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Donovan, R.J.; Jalleh, G.; Pescud, M. Predictors of positive outcomes of a school food provision policy in Australia. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, K.; Nathan, N.; Wolfenden, L.; Wiggers, J.; Sutherland, R.; Wyse, R.; Yoong, S.L. Validity of four measures in assessing school canteen menu compliance with state-based healthy canteen policy. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2016, 27, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, K.; Nathan, N.; Grady, A.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Wiggers, J.; Yoong, S.L.; Wolfenden, L. Barriers to implementation of a healthy canteen policy: A survey using the theoretical domains framework. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2018, 30, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmawati, N.; Manan, W.; Jamil, N.; Hanafi, N.; Rahman, R. How Healthy Is Competitive Food Served at Primary School Canteen in Malaysia? Int. Med. J. 2017, 24, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, N.J.; Steyn, N.P.; Myburgh, N.G.; Nel, J.H. Food items consumed by students attending schools in different socioeconomic areas in Cape Town, South Africa. Nutrition 2006, 22, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, J.; Scragg, R.; Schaaf, D.; Fitzgerald, E.; Wilson, N. Correlates of body mass index among a nationally representative sample of New Zealand children. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2007, 2, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.; Bressan, A.; Langelaan., C.; Mallon., A.; Palermo., C. Australian school canteens: Menu guideline adherence or avoidance? Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyse, R.; Wiggers, J.; Delaney, T.; Ooi, J.Y.; Marshall, J.; Clinton-McHarg, T.; Wolfenden, L. The price of healthy and unhealthy foods in Australian primary school canteens. Aust. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, R.S.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Alexander, M.; Scanlon, K.S.; Serdula, M.K. Dietary Assessment Methods among School-Aged Children: Validity and Reliability. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S11–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.M.; Han, E.; Chaloupka, F.J. Economic contextual factors, food consumption, and obesity among U.S. adolescents. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity Geneva; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.B.; Gaffney, M.; Nairn, K. Health rights in secondary schools: Student and staff perspectives. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 19, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Food and Nutrition Policy for Schools: A Tool for the Development of School Nutrition Programmes in the European Region; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Nutrition Friendly School Initative (NFSI) 2012. Available online: https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/nutrition_friendly_schools_initiative/en/ (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide. Helping You Eat A Healthy, Balanced Diet. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Downs, S.M.; Farmer, A.; Quintanilham, M.; Berry, T.R.; Mager, D.R.; Willows, N.D.; McCargar, L.J. From paper to practice: Barriers to adopting nutrition guidelines in schools. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, C.G.; Vasconcelos Fde, A.; Andrade, D.F.; de Schmitz, B.A. First law regulating school canteens in Brazil: Evaluation after seven years of implementation. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2009, 59, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.; Cummins, S.; Clark, C.; Stansfeld, S. Does the local food environment around schools affect diet? Longitudinal associations in adolescents attending secondary schools in East London. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, B.M.; Kliemann, N.; Silva, D.P.; Colussi, C.F.; Proenca, R.P. Availability and price of food products with and without trans fatty acids in food stores around elementary schools in low- and medium-income neighborhoods. Eco. Food Nutr. 2013, 52, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, W.; Essegbey, G.; Frempong, G.; Ruivenkamp, G. Understanding the concept of food sovereignty. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 20, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKerchar, C.; Smith, M.; Stanley, J.; Barr, M.; Chambers, T.; Abel, G.; Lacey, C.; Gage, R.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Signal, L. Food store environment examination—FoodSee: A new method to study the food store environment using wearable cameras. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 1757975919859575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetateanu, A.; Jones, A. How can GPS technology help us better understand exposure to the food environment? A systematic review. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, R.J.; Schuchter, J.; Rutt, C.; Seto, E.Y. Measuring the food environment and its effects on obesity in the United States: A systematic review of methods and results. J. Commu. Health 2015, 40, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.; Hankins, S.; Jilcott, S. Measures of the consumer food store environment: A systematic review of the evidence 2000-2011. J. Comm. Health 2012, 37, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Kalamatianou, S.; Drewnowskim, A.; Kulkarni, B.; Kinra, S.; Kadiyala, S. Food Environment Research in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E.; Radley, D.; Morris, M.; Hobbs, M.; Christensen, A.; Marwa, W.L.; Morrin, A.; Griffiths, C. A systematic review employing the GeoFERN framework to examine methods, reporting quality and associations between the retail food environment and obesity. Health Place 2019, 57, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).