Scale-Up of Doppler to Improve Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring in Tanzania: A Qualitative Assessment of National and Regional/District Level Implementation Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the facilitators and barriers to scale-up of Doppler?

- What lessons can be learned from Tanzania’s experience of scale-up of the HBB program?

- Who needs to do what to scale up Doppler in Tanzania?

2. Methods

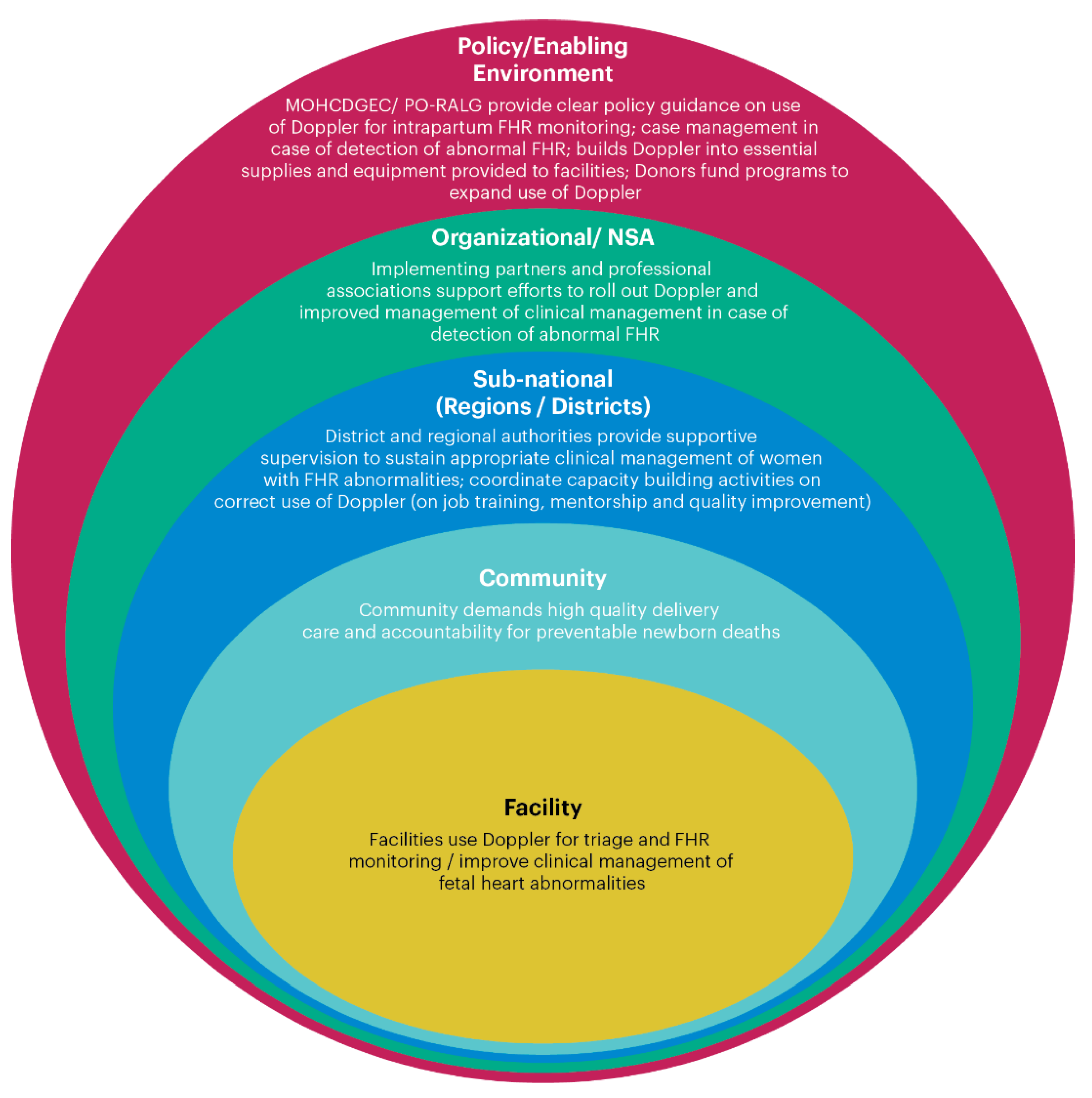

2.1. Social Ecological Framework for Scaling Up Doppler in Intrapartum Care

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Procedures and Study Tool

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Costs

3.1.1. Purchasing Dopplers for Health Facilities

If there is anything that is not in the budget, that would be a barrier for the facility to buy. It doesn’t matter how much it costs, it’s the issue of entering it into the normal yearly budget of every facility.

For example, a Pinard stethoscope costs about 5 US dollars compared to the Doppler, which costs about 200 US dollars. If you compare in terms of the prices, the Doppler looks to be expensive. But in terms of functionalities, we find that Doppler saves a lot of time, and it’s easier to use.

3.1.2. Procurement Processes

I proposed, why don’t you buy a fridge powered by solar? They said they can do that, but after 6 months it was still on procurement. That year the budget closed with 6 million shillings still in the budget (and no refrigerator).

3.2. Appropriateness

3.2.1. Training

Updates should focus on how to give high-quality care, on an on-job training basis.

The training should be mentorship, not classroom learning… [W]e can now see vividly that this helps someone to acquire that skill.

The issue is not just to put the Doppler at the bed of a pregnant woman, but also to know the concept behind the Doppler. Otherwise it can be there, but the interpretation of that data? The midwife may not think that the woman is in danger and take action.

Use the Regional and Council Health Management Teams (RHMT and CHMT) to train the providers at the level of the facility. I think that will really cut the cost, because we know that the CHMT and RHMT have regular supportive supervision at the facility … while they are going for that regular supervision, they go with the plan of training people.

We as regional supervisors, progressively need to supervise and sensitize … [W]e must make sure we work together with Councils as they have the capacity to reach all facilities. Emphasis must go on the facility in-charges who ensure that intended women get the service.

I think first and foremost, we need to develop guidelines—guidelines for use of Doppler, specifically.

3.2.2. Levels of Care

3.2.3. Practicability Barriers

The other note I want to make is that Doppler alone is not going to improve intrapartum care…. [A]reas like training of the personnel and staffing should come together.

3.2.4. Lessons Learned from HBB Scale-Up

HBB has contributed a lot to improve the newborn’s conditions … [I]t has rescued a lot of babies who had nearly died but were saved due to availability of these services in health facilities.

HBB is among the very successful programs that has been taken up here in Tanzania.

The barrier, or can I say challenge, to HBB was the availability of equipment … [I]n most of the government facilities, you find that there are so many clients … even when the equipment is there to help the baby survive, it is inadequate in quantity.

HBB in most parts of this country is not monitored—even at the regional level. It has been scaled up and nobody is concerned with monitoring—this is bad. You should monitor everything to see its effectiveness, see its applicability, to see the challenges.

3.3. Acceptability and Alignment with National Priorities

Over the past 15 years … we have seen a lot of emphasis on getting women to deliver at the health facilities. And we’ve done very well on that. We’ve moved from less than 40% hospital delivery to almost 63%, but we have not seen a significant reduction in infant mortality. And we ask why? Because it looks like we have moved these deaths from the community to the health facility … [T]hese facilities are not prepared to receive that influx of mothers. You see? So currently the government putting a lot of emphasis on improving the quality of intrapartum care.

Our data supports that if you use Doppler… any Doppler, the quality of intrapartum care becomes better and the outcomes are better. I think that’s the most important driver because we all want to reduce perinatal mortality… So, if somebody’s asking you, why do you want this? We have the evidence.

3.3.1. Acceptability to Health Care Providers

If we have the room to get a device which can assist the midwife to monitor fetal heart rate, I think we should be very positive. We are always telling our people to shout for help, and if this device really assists them to shout for help, why should we wait? We need it right now. I’m not the one budgeting, but as a midwife, I think we need this device. We need to advocate to the management to see the importance of this one.

One of the key issues which needs to change is attitude (of the health care provider). Change your attitude, and then we will make sure that the new technology will improve intrapartum care … and not only the health care provider, mothers too. Because some of them don’t like to hear the fetal heartbeat. We need to get the mother and health care providers aware the advantage of using the Doppler.

Availability of Doppler actually simplifies work for the provider in reducing the need for counting and using a watch (associated with use of Pinard fetoscope).

Any innovation which comes in, you don’t expect to be accepted right away.… [B]ecause people want to stay in their comfort zone. So, if a person is used to having a Pinard stethoscope, it’s maybe comfortable to continue using the Pinard stethoscope because he has been doing that over years and years.… So, you have those kinds of people who will take the innovation when they get it, but you have those people who will not take it from the beginning.… We should be aware of that. That even though this innovation may be good, we should not expect immediate acceptance by all.

3.3.2. Alignment with National Priorities

When we read the Road Map you see that it aims at certain goals, one of them being the reduction of maternal death as well as newborn and perinatal death. So, proper monitoring during labor will definitely help to identify babies in distress and respective intervention can be performed, timely.

I think the best way (to scale up Doppler) is to make sure that the intervention is clearly shown in the One Plan II. From the One Plan II, you can get all of these interventions focusing on the Doppler, where we can plan to train all of these providers, make sure the Dopplers are available, [and] the distribution is good.

One of the issues, which is alarming, is the number of newborns dying in our health facilities. If you go through our statistics, the number of newborns reported dead, one of the leading causes is birth asphyxia … so if you are in a position to establish that at the time the woman is delivering, that baby survives, that will be good!

We need to keep the data to see how this will help our people so that the government has a clear reason and a clear vision for using it to reduce death.

3.4. Stakeholders’ Roles and Responsibilities

Key: Ministry of Health, Child Development, Gender, the Elderly and Children: MOHCDGEC; President’s Office/Regional and Local Governance: PO-RALG; Tanzania Midwifery Association: TAMA; Tanzania Nurse and Midwives Council: TNMC; Association of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Tanzania: AGOTA

There are so many updates sometimes, it is not easy for the government facilities to get it … the implementing partners have updates and can build capacity of the health care providers.

As far as I know, the Government of Tanzania has not really budgeted, or adopted the use of the Moyo (Doppler) throughout the country, hopefully they would be able to do that. Without that, a scale-up of Moyo (Doppler) will suffer from the same disease: donor dependence and lack of buy-in from the local resources.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lawn, J.E.; Blencowe, H.; Waiswa, P.; Amouzou, A.; Mathers, C.; Hogan, D.; Flenady, V.; Frøen, J.F.; Qureshi, Z.U.; Calderwood, C.; et al. Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016, 387, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Bianchi-Jassir, F.; Say, L.; Chou, D.; Mathers, C.; Hogan, D.; Shiekh, S.; Qureshi, Z.U.; You, D.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: A systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e98–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, S.; Cousens, S.N.; Lawn, J.E. Estimation of daily risk of neonatal death, including the day of birth, in 186 countries in 2013: A vital-registration and modelling-based study. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e635–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Bahl, R.; Lawn, J.E.; Salam, R.A.; Paul, V.K.; Sankar, M.J.; Blencowe, H.; Rizvi, A.; Chou, V.B.; et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014, 384, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar, A.; Sheiner, E.; Hallak, M.; Katz, M.; Mazor, M.; Shoham-Vardi, I. Abnormal fetal heart rate tracing patterns during the first stage of labor: Effect on perinatal outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidanto, H.L.; Mogren, I.; van Roosmalen, J.; Thomas, A.N.; Massawe, S.N.; Nystrom, L.; Lindmark, G. Introduction of a qualitative perinatal audit at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langli Ersdal, H.; Mduma, E.; Svensen, E.; Sundby, J.; Perlman, J. Intermittent detection of fetal heart rate abnormalities identify infants at greatest risk for fresh stillbirths, birth asphyxia, neonatal resuscitation, and early neonatal deaths in a limited-resource setting: A prospective descriptive observational study at Haydom Lutheran Hospital. Neonatology 2012, 102, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosmalen, J.V.A.N. Perinatal mortality in rural Tanzania. Br. J. Obs. Gyne. 1989, 96, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, J. Appropriate medical technology for perinatal care in low-resource countries. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 2008, 28, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamala, B.A.; Ersdal, H.L.; Dalen, I.; Abeid, M.S.; Ngarina, M.M.; Perlman, J.M.; Kidanto, H.L. Implementation of a novel continuous fetal Doppler (Moyo) improves quality of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring in a resource-limited tertiary hospital in Tanzania: An observational study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, K.; Nyoni, R.; Mulambo, T.; Kasule, J.; Jacobus, E. Randomised controlled trial of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. BMJ 1994, 308, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byaruhanga, R.; Bassani, D.G.; Jagau, A.; Muwanguzi, P.; Montgomery, A.L.; Lawn, J.E. Use of wind-up fetal Doppler versus Pinard for fetal heart rate intermittent monitoring in labour: A randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamala, B.; Kidanto, H.L.; Mduma, E.R.; Perlman, J.M.; Ersdal, H.L. Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring using a handheld Doppler versus Pinard stethoscope: A randomized controlled study in Dar es Salaam. Int. J. Womens Health 2018, 10, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mdoe, P.F.; Ersdal, H.L.; Mduma, E.; Moshiro, R.; Dalen, I.; Perlman, J.M.; Kidanto, H. Randomized controlled trial of continuous Doppler versus intermittent fetoscope fetal heart rate monitoring in a low-resource setting. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangesi, L.; Hofmeyr, G.; Woods, D. Assessing the preference of women for different methods of monitoring the fetal heart in labour. S. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009, 15, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rivenes Lafontan, S.; Sundby, J.; Ersdal, H.L.; Abeid, M.; Kidanto, H.L.; Mbekenga, C.K. “I was relieved to know that my baby was safe”: Women’s attitudes and perceptions on using a new electronic fetal heart rate monitor during labor in Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afnan-Holmes, H.; Magoma, M.; John, T.; Levira, F.; Msemo, G.; Armstrong, C.E.; Martínez-Álvarez, M.; Kerber, K.; Kihinga, C.; Makuwani, A.; et al. Tanzania’s countdown to 2015: An analysis of two decades of progress and gaps for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health, to inform priorities for post-2015. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e396–e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Evaluation Platform (NEP). Understanding Tanzania Mainland’s Slow Progress Towards Reducing Maternal Mortality: An Evaluation of the One Plan for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (2008–2015); NEP: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. National Service Quality Improvement Tool for BEmONC; United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arlington, L.; Kairuki, A.K.; Isangula, K.G.; Meda, R.A.; Thomas, E.; Temu, A.; Mponzi, V.; Bishanga, D.; Msemo, G.; Azayo, M.; et al. Implementation of “Helping Babies Breathe”: A 3-year experience in Tanzania. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, J.; Martineau, N.; Kairuki, A.; Mponzi, V.; Meda, A.R.; Isangula, K.G.; Thomas, E.; Plotkin, M.; Chan, G.J.; Davids, L.; et al. Validation of a novel tool for assessing newborn resuscitation skills among birth attendants trained by the Helping Babies Breathe program. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 131, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, M.; Bishanga, D.R.; Temu, A.; Njozi, M.; Thomas, E.; Mponzi, V.; Arlington, L.; Msemo, G.; Azayo, M.; Kairuki, A.; et al. Structured on-the-job training to improve retention of newborn resuscitation skills: A national cohort Helping Babies Breathe study in Tanzania. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossius, C.; Lotto, E.; Lyanga, S.; Mduma, E.; Msemo, G.; Perlman, J.; Ersdal, H.L. Cost-effectiveness of the “Helping Babies Breathe” program in a missionary hospital in rural Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, S.; Arlington, L.; Brenan, S.; Kairuki, A.K.; Meda, A.R.; Isangula, K.G.; Mponzi, V.; Bishanga, D.; Thomas, E.; Msemo, G.; et al. Cost analysis of large-scale implementation of the “Helping Babies Breathe” newborn resuscitation-training program in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Fuqua, J. The social ecology of health: Leverage points and linkages. Behav. Med. 2000, 26, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.K.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.T.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, E. Diffusion of Innovation, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins, S.; Valsangkar, B.; Patterson, J.; Wall, S.; Riggs-Perla, J. Caution needed to avoid empty scale-up of kangaroo mother care in low-income settings. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fetal Monitoring During Labour; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mdoe, P.F.; Ersdal, H.L.; Mduma, E.; Perlman, J.; Moshiro, R.; Wangwe, P.; Kidanto, H. Intermittent fetal heart rate monitoring using a fetoscope or hand held Doppler in rural Tanzania: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mdoe, P.F.; Ersdal, H.L.; Mduma, E.; Moshiro, R.; Kidanto, H.; Mbekenga, C. Midwives’ perceptions on using a fetoscope and Doppler for fetal heart rate assessments during labor: A qualitative study in rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.C.; Bishanga, D.R.; Currie, S.; Rawlins, B.; Tibaijuka, G.; Makuwani, A.; Ricca, J.; George, J.; Mpogoro, F.; Abwao, S.; et al. From training to workflow: A mixed-methods assessment of integration of Doppler into maternity ward triage and admission in Tanzania. J. Glob. Health Reports 2019, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. Evidence Synthesis for Health Policy and Systems: A Methods Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, L.; Kohl, R.; Ved, R.R. Nine Steps for Developing a Scaling-up Strategy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.A.; Kelley, C.; Yankey, N.; Birken, S.A.; Abadie, B.; Damschroder, L. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestone, J.; Johnson, P.; Fullerton, J.; Carr, C.; Alderman, J.; BonTempo, J. Effective in-service training design and delivery: Evidence from an integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchiolo, M.; Cavallin, F.; Bertuola, F.; Pizzol, D.; Segafredo, G.; Wingi, O. Effect of a low-dose/high-frequency training on real-life neonatal resuscitation in a low-resource setting. Neonatology 2018, 114, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, P.; Nelson, A.; Asiedu, A.; Addo, E.; Agbodza, D.; Allen, C.; Appiagyei, M.; Bannerman, C.; Darko, P.; Duodu, J.; et al. Accelerating newborn survival in Ghana through a low-dose, high-frequency health worker training approach: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Tanzania Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities; UNICEF: Geneva Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/country_profiles/United%20Republic%20of%20Tanzania/country%20profile_TZA.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Willcox, M.; Harrison, H.; Asiedu, A.; Nelson, A.; Gomez, P.; LeFevre, A. Incremental cost and cost-effectiveness of low-dose, high-frequency training in basic emergency obstetric and newborn care as compared to status quo: Part of a cluster-randomized training intervention evaluation in Ghana. Glob. Health 2017, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Interviewees and Roles | Organization |

|---|---|

| (2) Senior advisors | Reproductive Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health Department, the President’s Office, Regional and Local Government (PO-RALG) |

| (2) Senior Advisors | Reproductive and Child Health Section, Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, the Elderly, and Children (MOHCDGEC) |

| (1) Registrar | Tanzania Nursing and Midwifery Council |

| (1) Reproductive and child health services coordinator | Regional Health Management Team, Mara |

| (1) Research scientist, subject matter expert | Haydom Lutheran Hospital |

| (1) Subject matter expert | Aga Khan Medical University |

| (1) Program specialist, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health | U.S. Agency for International Development, Tanzania |

| Domain | Questions |

|---|---|

| Costs |

|

| Appropriateness |

|

| Acceptability |

|

| Summary Of Responses To: “What Are National Priorities for Improving Intrapartum Care in Tanzania?” | Alignment with Doppler Scale-Up | |

|---|---|---|

| Description | Level * | |

| Ensure competent, high-quality labor and delivery care, including respectful maternity care, to reduce the number of deaths in prenatal and intrapartum care. | Improved fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring could potentially reduce perinatal death in the intrapartum period. | High |

| Ensure high-quality newborn care. | Use of Doppler may improve FHR monitoring and thus newborn care. | |

| During intrapartum care, monitor and document the FHR in the partograph. | Doppler can improve FHR monitoring for better use of partograph. | |

| Record labor, delivery, and post-delivery client management so the facility can review care. | Doppler can help improve FHR information for quality of care review or for perinatal death audit. | |

| Increase the number of skilled birth attendants; ensure sufficient supply of lifesaving commodities, equipment, and medicines; and build health care provider capacity. | Having a sufficient supply of Doppler devices may help save newborn lives. | Medium |

| Manage preterm babies in regional hospitals. | Use of Doppler for FHR monitoring may save lives of preterm babies for treatment in newborn intensive care units. | |

| Ensure that every mother delivers at a facility with a skilled provider. | Clients may prefer Doppler, which may contribute to better experience and thus higher attendance at care. | Low |

| Upgrade facilities to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care (CEmONC), i.e., cesarean services; promote facility deliveries, early booking, and regular antenatal care (ANC) attendance. | Use of Doppler to monitor FHR may result in more referral to cesarean services. However, use of Doppler is not necessarily associated with the upgrade from BEmONC to CEmONC. | |

| Book ANC appointments early. | Use of Doppler for intrapartum FHR monitoring is not connected to ANC. | None |

| Build new health facilities. | Use of Doppler for intrapartum FHR monitoring is not connected to building new health facilities | |

| Level | Key Finding/Needs for Scale-Up | Lessons Learned from HBB Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Policy-enabling environment (Government of Tanzania and international donors) |

| Use both costing and program monitoring data to track program results. |

| Nonstate actors/organizational environment (national and international civil society organizations and professsional associations) |

| Training approaches should be evidence-based, and include onsite, low-dose, high-frequency training and clinical mentoring. |

| Subnational level (regions and districts) |

| Sufficient supervisory and technical skills must be available at the district level. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plotkin, M.; George, J.; Bundala, F.; Tibaijuka, G.; Njonge, L.; Lemwayi, R.; Drake, M.; Bishanga, D.; Rawlins, B.; Ramaswamy, R.; et al. Scale-Up of Doppler to Improve Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring in Tanzania: A Qualitative Assessment of National and Regional/District Level Implementation Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061931

Plotkin M, George J, Bundala F, Tibaijuka G, Njonge L, Lemwayi R, Drake M, Bishanga D, Rawlins B, Ramaswamy R, et al. Scale-Up of Doppler to Improve Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring in Tanzania: A Qualitative Assessment of National and Regional/District Level Implementation Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061931

Chicago/Turabian StylePlotkin, Marya, John George, Felix Bundala, Gaudiosa Tibaijuka, Lusekelo Njonge, Ruth Lemwayi, Mary Drake, Dunstan Bishanga, Barbara Rawlins, Rohit Ramaswamy, and et al. 2020. "Scale-Up of Doppler to Improve Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring in Tanzania: A Qualitative Assessment of National and Regional/District Level Implementation Factors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061931

APA StylePlotkin, M., George, J., Bundala, F., Tibaijuka, G., Njonge, L., Lemwayi, R., Drake, M., Bishanga, D., Rawlins, B., Ramaswamy, R., Singh, K., & Wheeler, S. (2020). Scale-Up of Doppler to Improve Intrapartum Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring in Tanzania: A Qualitative Assessment of National and Regional/District Level Implementation Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1931. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061931