Mindfulness and Coaching to Improve Learning Abilities in University Students: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Regulated Learning, Emotion Regulation, and Achievement Motivation

1.2. Mindfulness

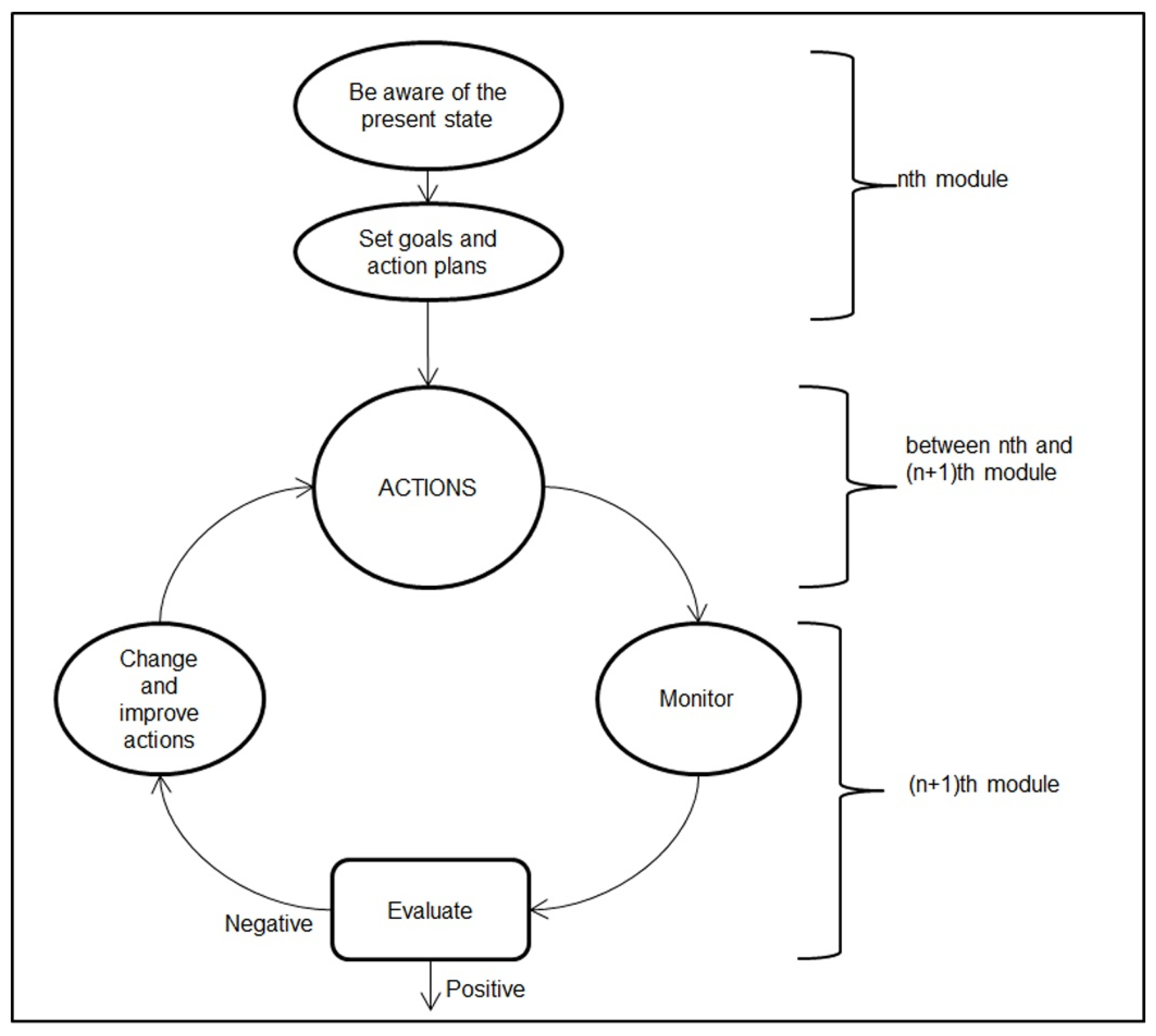

1.3. Coaching

1.4. Mindfulness-Based Group Coaching

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Materials

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Measures and Data Analysis

- (1)

- The MAAS was validated in Italy by Veneziani and Voci [74]. The MAAS was designed to measure the level of awareness of the present-moment experience [38], and it consists of 15 items on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 7 (almost never) (for example, “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present.”). A total score was obtained by summing and averaging the single items, yielding a total score ranging from 1 to 7. Higher scores indicated higher levels of mindfulness. The Cronbach’s alpha value for this questionnaire was 0.72 at the pre-test and 0.85 at the post-test.

- (2)

- The Study Approach Questionnaire (QAS) is part of the AMOS questionnaire set [72] that investigates self-regulation study abilities. The QAS consists of 50 total items divided into 5 sections of 10 items that cover the following aspects:

- Organization, that is, the ability to organize and schedule time (for example, “At the beginning of the afternoon, I review all the things I have to do”);

- Elaboration, that is, the degree of elaboration of the study material (“When I read, I try to formulate questions about the content”);

- Self-evaluation, that is, the ability to monitor and self-evaluate one’s own learning (“When I have not studied enough, I’m aware of it”);

- Use of strategies, that is, the ability to use strategies to prepare for an exam (“I try to predict the type of exam/task that awaits me”);

- Metacognition, that is, the ability to be aware of the functioning of one’s mind (“I like to dwell on thinking about how my mind works”).The participants responded to each item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The total score was obtained by summing and averaging the single items, yielding a total score ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicated higher levels of efficacy in the study approach. The Cronbach’s alpha values were found to be 0.75 and 0.83 for pre- and post-test organization, respectively; 0.49 and 0.62 for pre- and post-test elaboration; 0.66 and 0.75 for pre- and post-test self-evaluation; 0.69 and 0.67 for pre- and post-test use of strategies; and 0.66 and 0.71 for pre- and post-test metacognition.

- (3)

- The Anxiety and Resilience Questionnaire (QAR) is part of the AMOS questionnaire set [72]. The QAR consists of 14 items, 7 for anxiety (“Anxiety about the exam prevents me from concentrating”) and 7 for resilience (“I overcome agitation and tension, and I recover from the moments of difficulty in study”), on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree) to 5 (totally agree). A total score was obtained by summing the single items, yielding a total score ranging from 7 to 35. High scores corresponded to high anxiety levels and high resilience levels. The Cronbach’s alpha values were found to be 0.91 for pre- and post-test anxiety and 0.62 and 0.49 for pre- and post-test resilience, respectively.

- (4)

- The Questionnaire on Beliefs (QC) is part of the AMOS Questionnaire [72]. The QC concerns the motivational aspects of academic study. Composed of 29 items, the QC is divided into 6 subscales, with 2 related to incremental theories of Self, 3 to self-confidence, and 1 to academic achievement goals:

- Incremental theories of Self: theory of one’s own entity/incremental intelligence (8 items, for example, “You have a certain degree of intelligence, and you can do very little to change it”) and theory of one’s own entity/incremental personality (6 items, for example, “Some people have a good personality; others do not, and they cannot change it a lot”). The items employ a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally agree) to 6 (totally disagree). Item responses for each participant were summed, yielding a total score ranging from 8 to 48 for intelligence and from 6 to 36 for personality. High scores for both aspects corresponded to an incremental theory of self, as defined by Dweck’s Self-theories [20].

- Self-confidence: confidence in one’s own intelligence (3 items, for example, “Choose between: (a) Usually I think I’m smart/(b) I wonder if I’m smart”). The participant had to choose between the statement (a) or (b) of every item. After that, as regard the chosen statement, he/she had to choose an item from a three-items scale (“not completely true”, “true”, “very true”). To these items it has been attributed a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6 corresponding to the following choices: 1 point = statement (b) and “very true” from the scale, 2 points = statement (b) and point “true” from the scale, 3 points = statement (b) and “not completely true” from the scale, 4 points = statement (a) and “not completely true” from the scale, 5 points = statement (a) and point “true” from the scale, 6 points = statement (a) and point “very true” from the scale. The item responses for each participant were summed, yielding a total score ranging from 6 to 18. High scores corresponded to good confidence in one’s own intelligence.Confidence in one’s own personality (3 items, for example, “(a) Choose between: When I meet new people, (b) I’m not sure I’ll like them/When I meet new people, I’m sure I’ll like them”). The participant had to choose between the statement (a) or (b) of every item. After that, he/she had to choose an item from a three-items scale (“not completely true”, “true”, “very true”). To these items it has been attributed a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 6 corresponding to the following choices: 1 point = statement (a) and “very true” from the scale, 2 points = statement (a) and “true” from the scale, 3 points = statement (a) and “not completely true” from the scale, 4 points = statement (b) and “not completely true” from the scale, 5 points = statement (b) and “true” from the scale, 6 points = statement (b) and “very true” from the scale. The item responses for each participant were summed, yielding a total score ranging from 6 to 18. High scores corresponded to good confidence in one’s own personality.Self-ability perception regarding study activities (5 items, for example, “What do you think about: Your study skills?”). The items had a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). Item responses for each participant were summed, yielding a total score for the measure ranging from 5 to 25. High scores corresponded to good perception of one’s study skills.

- Academic achievement goals (4 items, for example, “In a study situation you prefer to face tasks that you already know/new tasks that you have not faced before.”). The participants had to choose one of the two sentences for each item. Each item had a score of 0 or 1. The item responses for each participant were summed, yielding a total score for the measure ranging from 0 to 4. Low scores corresponded to performance goals, and high scores corresponded to mastery goals.The following Cronbach’s alpha value emerged: 0.92 for pre- and post-test theory of intelligence; 0.87 and 0.89 for pre- and post-test theory of personality, respectively; 0.82 and 0.77 for pre- and post-test confidence in one’s own intelligence, respectively; 0.78 and 0.67 for pre- and post-test confidence in one’s own personality, respectively; 0.69 and 0.64 for pre- and post-test perception of self-ability, respectively; and 0.86 and 0.75 for pre- and post-test academic achievement goals, respectively.

- (5)

- A follow-up self-report survey was administered to the students in the intervention group six months after the end of the intervention. The students were asked to answer nine open-ended questions regarding their opinions about the training (see Section 3.7 for the questions). Another follow-up self-report survey was administered one year after the end of the intervention to analyze the average grade achieved by the participant. The surveys were anonymously filled out using SurveyMonkey software.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Post-Treatment Analyses

3.3. Self-Awareness of the Present-Moment Experience

3.4. Self-Regulated Study

3.5. Emotional Regulation

3.6. Motivation

3.7. Follow-up Self-Report Surveys

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bjork, R.A.; Dunlosky, J.; Kornell, N. Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 417–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panadero, E. A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenbrink, E.A.; Pekrun, R. (Eds.) Students’ emotions and academic engagement: Introduction to the special issue. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P.A.; Pekrun, R. (Eds.) Emotion in Education; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. An achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A. Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, C.; Ronconi, L.; De Beni, R. What Makes a Good Student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winne, P.H.; Nesbit, J.C. The psychology of academic achievement. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 653–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlosky, J.; Rawson, K.A.; Marsh, E.J.; Nathan, M.J.; Willingham, D.T. Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2013, 14, 4–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpicke, J.D. Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderstrom, N.C.; Bjork, R.A. Testing facilitates the regulation of subsequent study time. J. Mem. Lang. 2014, 73, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Rohrer, D. The effects of interleaved practice. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2010, 24, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. Theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and instructional issues in research on metacognition and self-regulated learning: A discussion. Metacognition Learn. 2009, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornoldi, C. Metacognition, Intelligence and Academic Performance. In Metacognition, Strategy Use, and Instruction; Waters, H.S., Schneider, W., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J.H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, S. Metacognitive Components in learning to learn approaches. Int. J. Psychol. A Biopsychosoc. Approach 2014, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development; Psychology Press/Taylor and Francis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A.J.; Murayama, K.; Pekrun, R. A 3 × 2 achievement goal model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, M.; Skaalvik, E.M. Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, K.; Schüz, B.; Schwarzer, R.; Norris, K. I believe, therefore I achieve (and vice versa): A meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keye, M.D.; Pidgeon, A.M. Investigation of the relationship between resilience, mindfulness, and academic self-efficacy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.B. Mindfulness meditation for increasing resilience in college students. Psychiatr. Ann. 2013, 43, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, D. Meta-cognition in mindfulness: A conceptual analysis. Psychol. Thought 2015, 8, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Towey, G.E. Long-term meditation: The relationship between cognitive processes, thinking styles and mindfulness. Cogn. Process. 2017, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, T.; Holas, P. Metacognitive model of mindfulness. Conscious. Cogn. 2014, 28, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, F.; Johnson, S.K.; Diamond, B.J.; David, Z.; Goolkasian, P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious. Cogn. 2010, 19, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Hölzel, B.K.; Posner, M.I. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2015, 16, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.; Slagter, H.A.; Dunne, J.D.; Davidson, R.J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, E.; Baker, R. The effects of student coaching in college: An evaluation of a randomized experiment in student mentoring. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. Work. Pap. Ser. 2011, 16881, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiorio, N.M.; Carney, P.A.; Kahl, L.E.; Bonura, E.M.; Juve, A.M. Coaching: A new model for academic and career achievement. Med. Educ. Online 2016, 21, 33480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lech, A.M.; van Nieuwerburgh, C.; Jalloul, S. Understanding the experience of PhD students who received coaching: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2018, 11, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. The impact of life Coaching on goal attainment, metacognition and Mental Health. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2003, 31, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassed, G.; Chambers, R. Mindful Learning: Reduce Stress and Improve Brain Performance for Effective Learning; ReadHowYouWant, Large Print: Sidney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, P.J.; Zajonc, A.; Scribner, M. The Heart of Higher Education: A Call to Renewal; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Roeser, R.W. (Eds.) Handbook of Mindfulness in Education: Integrating Theory and Research into Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Brown, K.W.; Astin, J.A. Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2011, 113, 493–528. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, A. Contemplative pedagogy: A quiet revolution in higher education. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2013, 2013, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; Gullone, E.; Allen, N.B. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, B.K.; Lazar, S.W.; Garda, T.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Ott, U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E. The Power of Mindful Learning; Da Capo Lifelong Books: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McConville, J.; McAleer, R.; Hahne, A. Mindfulness training for health profession students: A systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled trials. Explor. J. Sci. Heal. 2017, 13, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Oman, D.; Thoresen, C.E.; Plante, T.G.; Flinders, T. Cultivating mindfulness: Effects on well-being. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 64, 840–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A. Mindfulness for well-being and stress management among college students. Couns. Wellness A Prof. Couns. J. 2017, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Canby, N.K.; Cameron, I.M.; Calhoun, A.T.; Buchanan, G.M. A brief mindfulness intervention for healthy college students and its effects on psychological distress, self-control, meta-mood, and subjective vitality. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, N. Mindfulness, coping self-efficacy and foreign language anxiety: A mediation analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 37, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, J.; Mañas, I.; Franco, C.; Cangas, A.J.; Soriano, E. Differential effect of level of self-regulation and mindfulness training on coping strategies used by university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, E.I.; Meppelink, R.; Bögels, S.M. Mindfulness in higher education: Awareness and attention in university students increase during and after participation in a mindfulness curriculum course. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, H.H.; Koo, M.; Tsai, T.H.; Chen, C.Y. Effects of a mindfulness meditation course on learning and cognitive performance among university students in Taiwan. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, M.D.; Morpeth, E. Effects of mindfulness meditation on college student anxiety: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramler, T.R.; Tennison, L.R.; Lynch, J.; Murphy, P. Mindfulness and the College Transition: The Efficacy of an Adapted Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention in Fostering Adjustment among First-Year Students. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmaro, L.A.; Salmon, P.; Naidu, H.; Rowe, J.; Phillips, K.; Rebholz, W.N.; Giese-Davis, J.; Cash, E.; Dreeben, S.J.; Bayley-Veloso, R.; et al. Association of Dispositional Mindfulness with Stress, Cortisol, and Well-Being Among University Undergraduate Students. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 4–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Valero, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Puertas-Molero, P. Use of Meditation and Cognitive Behavioral Therapies for the Treatment of Stress, Depression and Anxiety in Students. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M. Mindfulness in Higher Education. Contemp. Buddhism 2011, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuechler, W.; Stedham, Y. Management education and transformational learning: The integration of mindfulness in an MBA course. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 42, 8–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwey, W.T. The Inner Game of Tennis, 1st ed.; Random House: NewYork, NK, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, S.J. Coaching for Performance: A Practical Guide to Growing Your Own Skills; Nicholas Brealey Publishing: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.W.; Grant, A.M. From GROW to GROUP: Theoretical issues and a practical model for group coaching in organizations. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2010, 3, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorell, R. Group coaching: A Practical Guide to Optimizing Collective Talent in Any Organization; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, M.J.; Spence, G.B. Mindfulness in coaching: Philosophy, psychology, or just a useful skill? In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Coaching and Mentoring; Passmore, J., Peterson, D., Freire, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, P.; Walsh, J. Sensory awareness mindfulness training in coaching: Accepting life’s challenges. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2008, 26, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, T. Mindfulness and coaching: Contemporary labels for timeless practices? In The SAGE Handbook of Coaching; Bachkirova, T., Spence, G., Drake, D., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2016; pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, G.B.; Cavanagh, M.J.; Grant, A.M. The integration of mindfulness training and health coaching: An exploratory study. Coach. Int. J. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 1, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, J.; Marianetti, O. The role of mindfulness in coaching. Coach. Psychol. 2007, 3, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Virgili, M. Mindfulness-based coaching: Conceptualization, supporting evidence and emerging applications. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 8, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Academic Skills Building. Available online: www.extension.harvard.edu/academic-skills-building (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- De Beni, R.; Moè, A.; Cornoldi, C.; Meneghetti, C.; Fabris, M.; Zamperlin, C.; Tona, G. Amos. Abilità e Motivazione Allo Studio: Prove di Valutazione e Orientamento per la Scuola Secondaria di Secondo Grado e L’università [Amos. Skills and Motivation to Study: Evaluation and Orientation Tests for Secondary School and University]; Edizioni Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Costabile, A.; Cornoldi, C.; De Beni, R.; Manfredi, P.; Figliuzzi, S. Metacognitive Components of Students’ Difficulties in the First Year of University. Int. J. High. Educ. 2013, 2, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Veneziani, C.A.; Voci, A. The Italian Adaptation of the Mindful Awareness Attention Scale and its Relation with Individual Differences and Quality of Life Indexes. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Gorell, R. 50 Top Tools for Coaching: A Complete Toolkit for Developing and Empowering People; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schraw, G.; Wadkins, T.; Olafson, L. Doing the Things We Do: A Grounded Theory of Academic Procrastination. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahawah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlmeier, P.; Eberth, J.; Schwarz, M.; Zimmermann, D.; Haarig, F.; Jaeger, S.; Kunze, S. The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 1139–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Modules | Activities | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | Sharing personal information and expectations. |

| Ice breaker game to create a comfortable space in the group. 10 min of meditation. | ||

| 2 | Awareness and metacognition | Raisin exercise from the MBSR protocol * Sharing insights in the group. |

| Training on metacognition: recognize all the cognitive activities that arose while reading and understanding a text. Sharing insights in the group. | ||

| Awareness continuum practice ** | ||

| 3 | Attention regulation | 20 min of guided meditation using an external object: a cloth hanger put in the center of the room. Sharing the experience with the group. |

| 20 min of guided meditation on an internal object: a stable image arises inside oneself. Sharing the experience with the group. 10 min of meditation. | ||

| 4 | Emotion regulation | Guided meditation on emotions. |

| Self-report questionnaire to map one’s own academic emotions. Sharing insights in the group. Training on emotion regulation: awareness of the anxiety that arose during a proposed problem solving. | ||

| Guided meditation on anxiety release. | ||

| 5 | Motivation | 20 min of meditation. Theories of Self: dyadic reciprocal interview and sharing in the group on what emerged. |

| Self-perception—role playing: group of three people taking turns in the roles “I am”, “I should be”, “I wish to be”. Sharing the insights. | ||

| Self-report questionnaire to become aware of actual academic goals. Sharing in group to set new goals. 10 min of meditation. | ||

| 6 | Study strategy and techniques: Planning to study | 30 min of meditation. Individual work to draft a personal study plan, taking into account exams to be completed, time available, and study load. 10 min of meditation. |

| 7 | Study strategy and techniques: Managing time | Training on the procrastination tendency: guided meditation on the emotions that arise when we have to start a study session. |

| Training on the cycle closure ***: dyadic reciprocal interview to define which cycles are open in the present moment and how to close or delay them. | ||

| Self-report questionnaire and individual work to define the personal rules that best fit the individual study session. Sharing in the group. 10 min of meditation. | ||

| 8 | Study strategy and techniques: Techniques | 20 min of meditation. Game on the different techniques: participant chooses a particular technique among interleaving practice, spaced retrieval, self-testing ****, group study, and organizing materials. Students reflect on it and then give a short presentation on the technique. 10 min of meditation. |

| 9 | Study strategy and techniques: Mnemonics | 20 min of meditation. Game on different mnemo-techniques: split the group into four dyads, each of them uses a different mnemo-techniques; the coach reads a list of words that the students memorize; the efficacy of the different techniques is compared. 10 min of meditation. |

| 10 | Conclusion | 10 min of meditation. Students presentations on the insights and benefits of the MEL (Mindful Effective Learning) course. |

| Assessed Variables | t (43) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | −0.89 | 0.38 |

| Organization | 2.84 | 0.007 |

| Elaboration | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| Self-assessment | −0.05 | 0.96 |

| Use of strategies | 1.5 | 0.14 |

| Metacognition | −0.53 | 0.60 |

| Anxiety | −0.44 | 0.66 |

| Resilience | −0.15 | 0.88 |

| Theory of own entity/incremental intelligence | 1.54 | 0.12 |

| Theory of own entity/incremental personality | 2.06 | 0.05 |

| Confidence in own intelligence | 0.13 | 0.90 |

| Confidence in own personality | −1.9 | 0.06 |

| Self-ability perception | 2.55 | 0.01 |

| Academic achievement goals | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| Self-Awareness | Intervention Group | Control Group | F (1,42) | p | η2p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Self-awareness | 4.85 (0.77) | 5.30 (0.84) | 4.66 (0.66) | 4.60 (0.79) | 8.17 | <0.01 | 0.16 | |

| Self-Regulated Study Title | Intervention Group | Control Group | F (1,38) | p | η2p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Organization | 3.52 (0.61) | 3.94 (0.75) | 3.97 (0.42) | 3.84 (0.52) | 13.0 | <0.01 | 0.25 |

| Elaboration | 3.58 (0.44) | 3.85 (0.45) | 3.67 (0.35) | 3.65 (0.41) | 8.98 | <0.01 | 0.19 |

| Self-evaluation | 3.72 (0.59) | 4.08 (0.49) | 3.71 (0.26) | 3.60 (0.37) | 29.38 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| Metacognition | 3.68 (0.59) | 3.99 (0.38) | 3.59 (0.48) | 3.47 (0.49) | 18.93 | <0.001 | 0.33 |

| Emotional Regulation Title | Intervention Group | Control Group | F (1,42) | p | η2p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Anxiety | 20.48 (7.96) | 15.81 (6.19) | 19.54 (6.39) | 19.04 (6.92) | 7.78 | <0.01 | 0.16 |

| Theory of Intelligence/Personality Title | Intervention Group | Control Group | F (1,41) | p | η2p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Theory of own entity/incremental intelligence | 28.33 (10.89) | 37.43 (11.66) | 32.71 (7.57) | 34.58 (6.45) | 6.96 | =0.012 | 0.14 |

| Theory of own entity/incremental personality | 18.00 (6.88) | 26.14 (7.33) | 21.96 (6.02) | 20.75 (6.45) | 22.17 | <0.001 | 0.35 |

| Self-Confidence Title | Intervention Group | Control Group | F (1,40) | p | η2p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | Pre-Test | Post-Test | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Confidence in own intelligence | 11.05 (4.82) | 14.48 (3.09) | 11.21 (3.74) | 11.42 (3.28) | 15.51 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| Questions | Answer | % |

|---|---|---|

| Do you think the MEL training was useful? | Yes | 100% |

| No | 0% | |

| If you think it was useful, what was particularly helpful for you? | Group sharing | 32% |

| Awareness and self-regulation improvement | 26% | |

| Awareness improvement | 21% | |

| Self-regulation improvement | 21% | |

| Regarding the contents of the training, would you remove or add something? | No | 37% |

| Not remove, but deepen some content | 26% | |

| Not remove, but add more meditation practice | 21% | |

| Not remove, but add more time | 16% | |

| What are the strengths of the training? | The ambience and the group sharing | 45% |

| The coach | 22% | |

| The content | 22% | |

| The focus on personal development | 11% | |

| What are the weaknesses of the training? | The lack of total time and the length of the modules | 50% |

| The location | 22% | |

| There are none | 17% | |

| Too little practice | 11% | |

| What would you improve? | I would add more time | 37% |

| I would improve the organization | 32% | |

| I would deepen some content | 16% | |

| None | 16% | |

| Do you think the MEL training has improved your academic performance? | Yes | 79% |

| No | 21% | |

| Is the overall duration of the training adequate? | Yes | 53% |

| No | 47% | |

| No because … I would expect more time for deepening the content | 78% | |

| No because … I would hold more meetings of lesser duration | 22% | |

| Is the duration of the single module adequate? | Yes | 68% |

| No | 32% | |

| No because … I would split the modules | 67% | |

| No because … I would schedule every module duration according to the content | 33% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corti, L.; Gelati, C. Mindfulness and Coaching to Improve Learning Abilities in University Students: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061935

Corti L, Gelati C. Mindfulness and Coaching to Improve Learning Abilities in University Students: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061935

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorti, Lorenza, and Carmen Gelati. 2020. "Mindfulness and Coaching to Improve Learning Abilities in University Students: A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061935

APA StyleCorti, L., & Gelati, C. (2020). Mindfulness and Coaching to Improve Learning Abilities in University Students: A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1935. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17061935