Community Engagement and Outreach Programs for Lead Prevention in Mississippi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

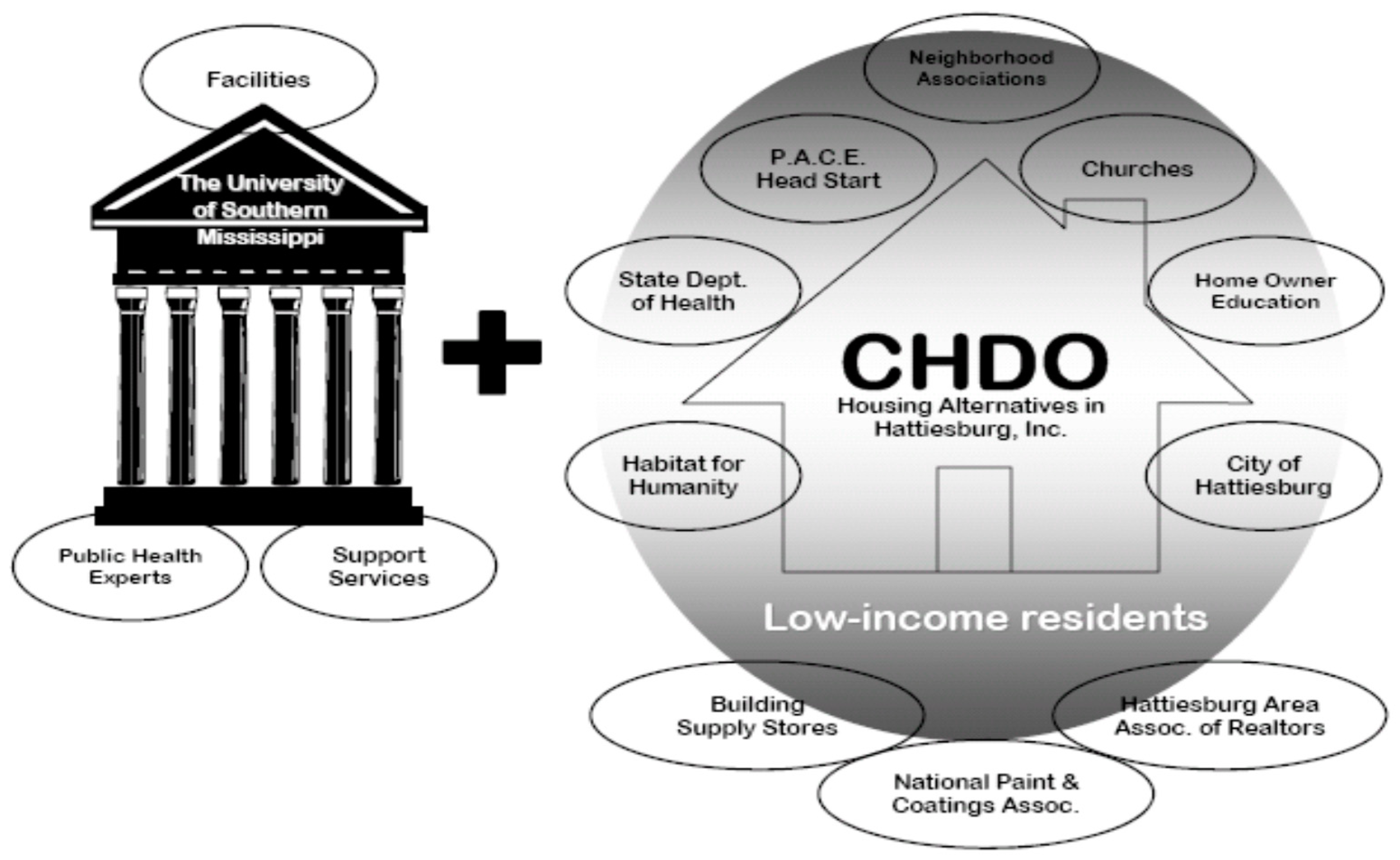

2.1. Community Partnership

2.2. Identification of High-Risk Populations

2.3. Project Goals, Activities, and Measurable Outcomes

2.4. Data Collection Instruments

3. Results

Impact of Hands-On Training, HUD Online Training, and Workshops

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Recognizes Lead Poisoning Prevention Week 2020. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-recognizes-lead-poisoning-prevention-week-2020 (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005. Available online: www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/publications/PrevLeadPoisoning.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. American Healthy Homes Survey—Lead and Arsenic Findings. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/AHHS_REPORT.PDF (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention in Newly Arrived Refugee Children: Tool Kit. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/publications/refugeetoolkit/refugee-tool-kit.htm (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Lead. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp.asp?id=96&tid=22 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Greig, J.; Thurtle, N.; Cooney, L.; Ariti, C.; Ahmed, A.O.; Ashagre, T.; Meredith, C. Association of blood lead level with neurological features in 972 children affected by an acute severe lead poisoning outbreak in Zamfara State, Northern Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, W.; Chen, Z.; Shi, K.; Sun, H.; Li, H.; Huang, L.; Bi, J. Adverse health effects of lead exposure on physical growth, erythrocyte parameters and school performances for school-aged children in eastern China. Environ. Int. 2020, 145, 106130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geier, D.A.; Kern, J.K.; Geier, M.R. Blood lead levels and learning disabilities: A cross-sectional study of the 2003–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptman, M.; Stierman, B.; Woolfe, A.D. Children with autism spectrum disorder and lead poisoning: Diagnostic challenges and management complexities. Clin. Pediatrics 2019, 58, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, E.; Borkowski, C.; Clark, S.; Brown, P. Educating speech-language pathologists working in early intervention on environmental health. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Maria, M.P.; Hill, B.D.; Kline, J. Lead (Pb) neurotoxicology and cognition. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2019, 8, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.K.; Haque, A.; Islam, M.; Bashar, S. Lead poisoning: An alarming public health problem in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Environmental Health. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/environmental-health/objectives (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Environmental Health. Screening for elevated blood lead levels. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Lead Based Paint Visual Assessment Training Course. Available online: https://apps.hud.gov/offices/lead/training/visualassessment/h00101.htm (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Prudential Foundation. Sesame Street Lead Away Video. Available online: https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-avast-securebrowser&hsimp=yhs-securebrowser&hspart=avast&p=Sesame+Street+Lead+Away+Video#id=1&vid=fa96193dfd221faac764df6ffb47eda2&action=click (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- University of Connecticut; Cooperative Extension System; College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. A Teacher’s Guide to How Mother Bear Taught the Children about Lead. Available online: https://kids.niehs.nih.gov/assets/docs/teachers_guide_508.pdf#:~:text=How%20Mother%20Bear%20Taught%20the%20Children%20about%20Lead%3A,individually%2C%20in%20small%20groups%2C%20or%20as%20a%20class (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). What Does the Regulation Require? Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/epa/lead/lead-outreach-partnerships-and-grants.html (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Environment Protection Agency. Lead Outreach, Partnerships and Grants. Lead Renovation, Repair and Painting (RRP) Rule. Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/epa/lead/lead-outreach-partnerships-and-grants.html (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Lasker, R.D.; Weiss, E.S. Broadening participation in community problem solving: A multidisciplinary model to support collaborative practice and research. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 14–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, N.L.; Lourie, R.J.; Gaughan, J. Lead awareness: North Philly style grant team. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kegler, M.C.; Malcoe, L.H.; Lynch, R.; Whitecrow-Ollis, S. A community-based intervention to reduce lead exposure among Native American children. Environ. Epidem. Toxicol. 2000, 2, 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Prevention of childhood lead toxicity. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Activity | Data Collection Procedures | Venue for Events | Training Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provide health education materials, educational training, and presentations to community-based organizations, child-care centers, and faith-based organizations | 1. Information, Education, Communication materials given out 2. Sign-in sheets 3. Videos, pictogram, color charts | Churches, Childcare centers, Elementary schools | Sesame Street Lead Away Video [18] (Age of children 3–5). A Teacher’s Guide to How Mother Bear Taught the Children about Lead Source: University of Connecticut. Cooperative Extension System. [19] |

| Host hands-on training on lead poisoning prevention at local home-builder retail stores | Exit survey | Lowe’s Home Depot Marvin’s Sherwin Williams | Hands-on training and educational materials |

| Provide lead prevention training for realtors | Follow-up survey | Housing Alternatives of Hattiesburg; Neighborhood Associations | HUD’s Lead-Based Paint Visual Assessment Training [17] |

| Provide intensive 8 h training on lead safe work practices to inspectors, contractors, and DIY workers | Follow-up survey | City of Hattiesburg Mayor’s Office | PowerPoint presentation; HUD’s Lead-Based Paint Visual Assessment Training [17] |

| Provide education on lead poisoning prevention through home-buyer education classes | Pre/Post test | Housing Alternatives of Hattiesburg; Neighborhood Associations | PowerPoint presentation |

| Provide training on lead-safe work practices to rental property owners | Follow-up survey | Churches | PowerPoint presentation |

| Mode of Training | Participants | Assessment | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health fairs | 467 | - | Distributed 1000 educational materials (leaflets and brochures) |

| Community events | 469 | - | Appeared in 25 health events. The City Mayor proclaimed the CLAP for Healthy Kids activities for lead prevention. |

| Kindergarten classes | 241 | - | Students offered a certificate of completion |

| Hands-on training at home-building retail stores | 25 | Exit survey | 23 out of 25 (92%) reported the training was useful or very useful |

| HUD’s online Lead-Based Paint Visual Assessment Training | 220 realtors; 75 inspectors, contractors, and DIY workers | Follow-up survey | 59.4%, 67.9%, 65.1% of the realtors identified soil, car batteries, and paint as sources of lead in the environment, respectively |

| A total of 62.3%, 48.1%, and 58.5%, at posttest, identified three complications—mental, physical, and psychological, respectively | |||

| Pre- and Post-test | The mean posttest score was significantly higher than the pretest scores (7.47 ± 2.07 vs. 6.60 ± 1.68, p = 0.04, respectively). | ||

| All the participants at a 2-month follow-up reported that they actually implemented what they had learned during the training on HUD curriculum on lead | |||

| Training workshops for home buyers and retail home owners | 91 | Exit survey | 90% mentioned the training was useful or very useful. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitra, A.K.; Anderson-Lewis, C. Community Engagement and Outreach Programs for Lead Prevention in Mississippi. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010202

Mitra AK, Anderson-Lewis C. Community Engagement and Outreach Programs for Lead Prevention in Mississippi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010202

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitra, Amal K., and Charkarra Anderson-Lewis. 2021. "Community Engagement and Outreach Programs for Lead Prevention in Mississippi" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010202

APA StyleMitra, A. K., & Anderson-Lewis, C. (2021). Community Engagement and Outreach Programs for Lead Prevention in Mississippi. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010202