Perceived Factors of Stress and Its Outcomes among Hotel Housekeepers in the Balearic Islands: A Qualitative Approach from a Gender Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Hotel Industry, Stress and Gender

1.2. The Job Demands-Resources Model and the Interdependencies between Work and Family Life

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Data Collection

- (1)

- Characteristics and organization of work of HHs.

- (2)

- Positive and negative aspects of HHs’ job.

- (3)

- Equipment and materials available.

- (4)

- Relationships among hotel workers and among HHs.

- (5)

- Factors of stress.

- (6)

- Health problems.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

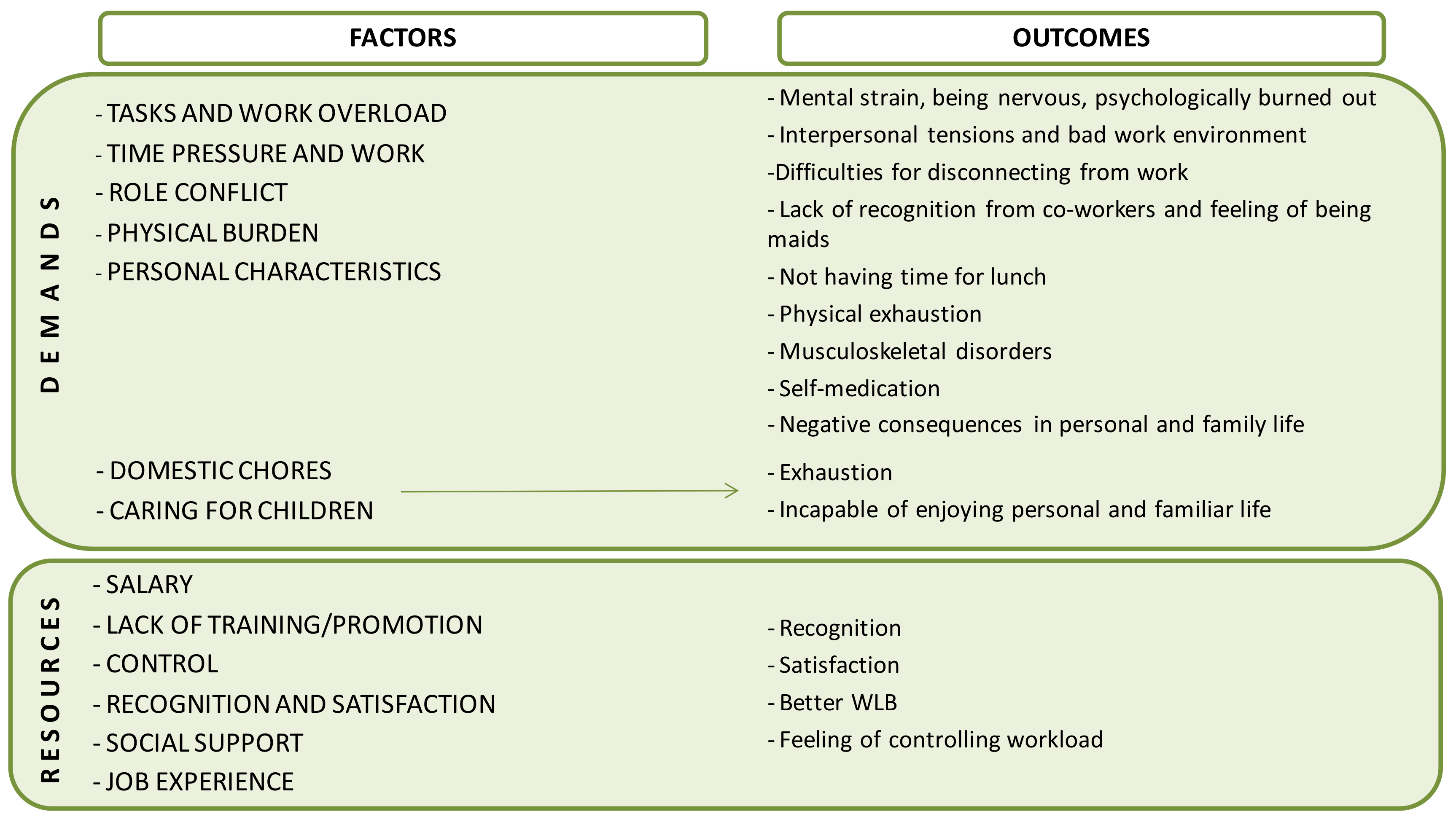

3.1. Demands Perceived

3.1.1. Tasks and Work Overload

HHi4. There are some stipulated times that we really don’t know where they come from. Because nobody has ever come to ask how much time you spend in one room. They calculate that in ten or fifteen minutes you have to finish an apartment no matter how full it is, no matter how much crap there is, whether they are clean or dirty or have kids whose toys are thrown all over the place. You have to leave all of that in a reasonable condition.

OHealth. The big problem that we find with the HHs is the diversity of all the activities. In the same hotel, two identical rooms, the workload is different, right? One thing is the family that comes back from the beach with all their things, sand, the toy boats… another thing is the family that didn’t go to the beach that day and their room is completely different.

HH5.3. Every single year they increase our workload; now we have to check the mini fridge, in every room check for coca cola, water, juices, crisps, candies, tea… everything. It’s [now all part of] our job [but it didn’t used to be].

Prev. They restock the minibar. They have a cart. They have bottles, they restock amenities, papers…Yes.

HH6.8. Now since they [hotel management] don’t want to compensate them, they change rooms. (…) Instead of six check-outs, you have ten. And that’s very hard for a HH.

- (1)

- The reduction of workforce, which implied having to assume more rooms to clean; not having enough staff to replace HHs on short sick leave; not having their days off when someone was ill; carrying out tasks not of their responsibility such as refilling mini-bars, etc.

PInsp. I think I have only found one who told me they were still the same [number of workers] as always (...). There were 15 [workers], but with the crisis they went down to 10; [but] the work was still completed [even with less staff]. Next year they went down to 8; [but] the work was still completed.

OHealth. A long term leave, (…) you get a contract, or go through a temp agency, or temporary contracts (…). Now, for example, it’s 7 in the morning and the director receives the “hey, I don’t feel well” and now there’s no time to-. So now the work that person had has to be divided among all the HHs including the ones from the afternoon shift.

- (2)

- The shortening of the length of stay of clients, which increased the number of check-out rooms to clean.

HH5.4. Since the crisis, people stay for two days, for three days, there are a lot of check-outs, they come, they go, this one has gone, this one hasn’t left yet… And it’s… besides the work, it’s stressful.

3.1.2. Time Pressure and Work Pace

HH5.1. I find it very stressful (…) the small amount of time they give you to finish such a complicated task.

HHi2. It’s not even an option for a person who’s working to be able to head down to pee because there’s no time. They don’t eat anything, and if I head down to eat, I can’t really eat because of all the stress I have.

SUP. While you go to another floor, several minutes have passed. Those minutes are dead time for the company. They don’t figure that in.

PInsp. Some tell you that they aren’t allowed to eat. (…) Come on, if you’re there from 7.30 until 4, at some point you have to eat. “Yes, but that means more of your time at work before you can leave. And you really just want to get home”. That’s what most of them tell me.

OHealth. It’s true that they sometimes tell us “I don’t even have time to head down”. (…) It’s also true that we analyze the workload and it’s not too different from the one who does have time to head down to eat.

Prev. In the room service department where the HH works alone at her pace, she has to finish 15, 16, 17, 18, however many rooms, but at her pace. I don’t see how that can be as stressful compared to, for example, [kitchen].

3.1.3. Role Conflict

- (1)

- From the reception desk: sometimes clients were sent to a room that was not ready yet, so HHs had to talk to clients without having nor enough time neither knowledge to explain the situation. Additionally, they thought that giving this kind of explanations was not their responsibility;

- (2)

- From clients, who asked for a blanket, for a pillow, for hangers, etc., so HHs had to interrupt their duties and go for them;

- (3)

- From the supervisor, who at the same time may receive demands from clients, from the reception desk and the dining hall- asking to clean a certain place.

HH6.1. The client says: “Hey, clean my room, I’m taking up my child to take a nap”. Okay. You have rooms on another floor. The director: “Hey, the clients on such and such floor want to check-out”. You head over there. You find a client in the hallway: “You haven’t cleaned my room”.

SUP. We are very, very, very stressed. Then there’s reception asking if a certain room is ready, and this client who wants a blanket, and this client who wants this, and this client who wants that. You have to go and take those things to them.

HH4.3. We’re maids to our own co-workers. They tell you to clean up their own work space.

SUP. In any case, management doesn’t tend to appreciate the work that HHs do. Mostly because, of course, when the girls do a good job, they never value that.

HH1.2. They don’t really appreciate us. We’re the maid… we’re the nannies for everybody. Because if the kitchen is dirty your own co-workers won’t help you.

HH1.3. From my point of view and in my experience, which is not very much, they give us a lot of work given what a good job they expect us to do.

3.1.4. Physical Burden

HHi4. And we use duvets. (…) imagine in every apartment having to change the covers for five or six duvets. By yourself.

OHealth. We know that the work done by the HHs is physical work that requires effort.

HH2.2. I had a better cart and they exchanged it for a much smaller one, but nothing fits in it.

HRDir: Hotels that have carpet, it’s much harder to move the bed. While hotels that don’t have carpet are better, or where the beds have rollers.

3.1.5. Personal Characteristics

HH5.4. Psychologically, I’m okay to work. But physically I hurt.

3.2. Resources Identified

3.2.1. Salary

HHi3. Financially, we could say a HH earns a decent salary.

HH3.5. The salary is not what you’d think. For the work we do, it’s badly paid. (…) We’re the bottom rung of the ladder. Earning less than a technician, earning less than a reception assistant…

3.2.2. Training/Promotion

HH6.5. I’m stuck in a rut because there aren’t really many opportunities for advancement or to level up or get a promotion. (…) There is no professional development at all.

Prev. All departments have their general training for occupational risk prevention and specific training for the job. Minimal, once a year each one. (…) We try to modify it every year or every two years, because the thing in job training (…) is that you are always explaining the same.

3.2.3. Control

- (1)

- Possibility of choosing the order in which to clean the rooms.

- (2)

- Knowing the habits of clients (e.g., time they got out of the room).

- (3)

- Days having less work, they could advance other tasks. The supervisor interviewed supported this practice as well.

- (4)

- Having certain rooms assigned to the same cleaner everyday allows them to have more control over the workload throughout the days. The HR director interviewed supported this view:

HH4.7. What’s more, you get organized yourself. What I mean is if a client tells me that they don’t want me to clean their room that day and I have a bit more flexibility with my time, I’ll do a little extra in the room I’m cleaning, for tomorrow. To get ahead.

HRDir. Because each one likes to have their space and to have it under control.

HH3.1. Go back to each of the do-not-disturbs, go back to all the ones who told you they were sleeping, go back to all the ones who said “I can’t right now”, “come back later, I’m eating”, “ten minutes, I’m heading down to the beach”. And that puts me behind schedule.

HH5.3. Because you really don’t know what you’re going to find when you open the room, if you’re going to be there for fifteen minutes, twenty or thirty.

3.2.4. Satisfaction and Recognition

HHi2. For me the schedule is the best part of the job because you have afternoon off, even though you’re really tired.

HH5.2. It is gratifying because the client knows you and says: “Oh, very nice, very nice, we like you.” And they’re pleased to tell you, you know? And then you feel good about the work you’ve done.

HH4.4: When new clients check-in and the card doesn’t work and they cannot open the door and you are like “Oh, don’t look at me, don’t see me.” And you see the old people: “Hey girl, this does not work.” And you are like “Oh, don’t call me.”

3.2.5. Social Support

HH1.1. We can’t help each other any longer because it’s impossible. Because she’s just as busy as me.

SUP. If they see that one of them isn’t doing well because she’s had problems because check-outs went badly, they lend each other a hand.

HH4.2. The relationships tend to be good.

HH4.4. You fight, argue, laugh, kiss

HH4.7. But the stress and the exhaustion

HH4.4. Why? Because they took your mop away, the mop is mine, the mop is yours, okay fine, you take it.

HH4.7. What brings that on? Stress. Exhaustion.

3.2.6. Experience

HH4.6. You have many years of experience, you know how to do your job well, but you don’t have the time or the energy to get it done and it produces anxiety where you just can’t take it anymore. You finish and leave work in tears.

3.3. Outcomes Reported of Demands-Resources Imbalanced

HH4.7. Constant stress. From the moment they give you the paper and you go home thinking about what you have to do the next day. (…) you don’t disconnect: “tomorrow I have so many check-outs, will I be able to get them done?”

HHi4. Work overload is taking a toll on our health.

HH5.2. I self-medicate (…) with pills, waiting until it really hurts so that I don’t have too much medication in my system. I’m tired of taking medication.

Prev. Young workers still don’t take anything. But yes, somebody in their late forties, early fifties who’s been working 20 odd years in the hotel industry has to take some kind of medication.

3.4. Work—Life Balance

HH2.4. You have time for yourself, if you have kids you have time for home, for everything. To have a bit of a social life. The people who have a split shift are there almost 24 h.

HH3.1. And I started because of the schedule. I had young kids and it worked well for me not to have a split shift. That was the only reason.

HH6.5. I have an eleven year old son, a one year old grandson, a thirty-two year old daughter and it’s stressful because I get home and my daughter tells me she’s coming over for lunch with my grandson. I should be happy but I’m not really. And I’m like, damn, now she’s coming over and I’m screwed. Because now I have to prepare food for four, clear the table…Because she’s coming to spend time with her mother, but her mother is thinking about all that she has to do…

HHi2. Because for the person who carries such a heavy workload on the outside and inside, it’s hard to have relationships and you can’t do everything with your daughter that you’d like to.

HH5.1. Because I went to the director and said: “I want to at least know one day that I’m getting off because if I have to see the doctor, they’re my personal things”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Encuesta de Población Activa. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176918&menu=resultados&idp=1254735976595#!tabs-1254736195129 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Scherzer, T.; Rugulies, R.; Krause, N. Work-related pain and injury and barriers to workers’ compensation among Las Vegas hotel room cleaners. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cañada, E. Las que Limpian los Hoteles. Historias Ocultas de Precariedad Laboral; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cañada, E. Too precarious to be inclusive? Hotel maid employment in Spain. Tour. Geogr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.J.W.; Lee, J.J.J.W.; Mun, H.J.; Lee, K.-J.; Kim, J.J. The relationship between musculoskeletal symptoms and work-related risk factors in hotel workers. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- EU-OSHA. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Available online: https://oshwiki.eu/wiki/Monitoring_new_and_emerging_risks#Combined_exposure_to_physical_and_psychosocial_risks (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. The world at work: Hotel room cleaners. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 70, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EU-OSHA; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Protecting Workers in Hotels, Restaurants and Catering; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; ISBN 9789291911639. [Google Scholar]

- Niño Lopez, M.A. Alteraciones músculo-esqueléticas de las camareras de piso. Mujeres y Salud 2002, 9, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, S.; Vossenas, P.; Krause, N.; Moriarty, J.; Frumin, E.; Shimek, J.A.M.; Mirer, F.; Orris, P.; Punnett, L. Occupational injury disparities in the US hotel industry. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krause, N.; Scherzer, T.; Rugulies, R. Physical workload, work intensification, and prevalence of pain in low wage workers: Results from a participatory research project with hotel room cleaners in Las Vegas. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2005, 48, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.S.; Ghosh, B.; Shaver, J.; Militzer, M.; Seng, J.; McCullagh, M.C. Blood pressure and job domains among hotel housekeepers. J. Health Dispar. Res. Pract. 2018, 11, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wami, S.D.; Dessie, A.; Chercos, D.H. The impact of work-related risk factors on the development of neck and upper limb pain among low wage hotel housekeepers in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.J.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. Work conditions and health and well-being of Latina hotel housekeepers. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.H.T. Hotel housekeeping occupational. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 17, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, C.F.; Liu, B.Z. Examining job stress and burnout of hotel room attendants: Internal marketing and organizational commitment as moderators. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 16, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.W.; Davis, K. Work stress and well-being in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burgel, B.J.; White, M.C.; Gillen, M.; Krause, N. Psychosocial work factors and shoulder pain in hotel room cleaners. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H.; Law, R. Work environment and well-being of different occupational groups in hospitality: Job Demand–Control–Support model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B.; Patiar, A. Workplace induced stress among operational staff in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1997, 16, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borralha, S.; de Jesus, S.N.; Pinto, P.; Viseu, J. Hotel employees: A systematic literature review. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2016, 12, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, T.; Krause, N. The impact of a worker health study on working conditions. J. Public Health Policy 2002, 23, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.J.; Sönmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Lemke, M.K. Perceived workplace mistreatment: Case of Latina hotel housekeepers. Work 2017, 56, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenbridge, S.; Moensted, M.L. The relationship between payment systems, work intensification and health and safety outcomes: A study of hotel room attendants. Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2011, 9, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.J.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Hatzudis, K.; Sönmez, S. Occupational exposures and health outcomes among Latina hotel cleaners. Hisp. Health Care Int. 2014, 12, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.J. Hotel housekeepers’ job stress. Recreat. Park. Tour. Public Health 2020, 4, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Bonnín, S.; García-Buades, M.E.; Caballer, A.; Zapf, D. Supportive climate and its protective role in the emotion rule dissonance—Emotional exhaustion relationship A multilevel analysis. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemberg, M.S.; Li, Y.; McConnell, D.S.; McCullagh, M.C.; Seng, J.S. Stressors, allostatic load, and health outcomes among women hotel housekeepers: A pilot study. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2019, 16, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU-OSHA; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Managing Psychosocial Risks with Cleaning Workers (E-FACTS 51); EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, H.; Einarsen, S. Violence at Work in Hotels, Catering and Tourism. 2003. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/publication/wcms_161998.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Krause, N.; Rugulies, R.; Maslach, C. Effort-reward imbalance at work and self-rated health of Las Vegas hotel room cleaners. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, B.L.; Harp, K.L.H.; Oser, C.B. Racial and gender discrimination in the stress process: Implications for african american women’s health and well-being. Sociol. Perspect. 2013, 56, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cifre, E.; Vera, M.; Signani, F. Women and men at work: Analyzing occupational stress and well-being from a gender perspective. Rev. Puertorriquena Psicol. 2015, 26, 172–191. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrero, S.; Saldaña, M.Á.M.; Rodriguez, J.G.; Ritzel, D.O. Influence of task demands on occupational stress: Gender differences. J. Saf. Res. 2012, 43, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el Trabajo VII Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Trabajo. Available online: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/96082/VII+Encuesta+Nacional+de+Condiciones+de+Trabajo%2C+2011/399f13f9-1b87-41de-bd7e-983776f8212a. (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Garrosa Hernández, E.; Gálvez Herrero, M. Género y Salud Laboral. In Salud Laboral, Riesgos Laborales Psicosociales y Bienestar Laboral; Moreno Jiménez, B., Garrosa Hernández, E., Eds.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gyllensten, K.; Palmer, S. The role of gender in workplace stress: A critical literature review. Health Educ. J. 2005, 64, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. A Resource perspective on the work-home interface. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, S.; Power, C. Socioeconomic gradients in psychological distress: A focus on women, social roles and work-home characteristics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) Encuesta de Empleo del Tiempo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176815&menu=resultados&idp=1254735976608#!tabs-1254736194826 (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Madsen, I.E.H.; Burr, H.; Siegrist, J. Adverse psychosocial working conditions and risk of severe depressive symptoms. Do effects differ by occupational grade? Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 23, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort / low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Xing, Y.; Gamble, J. Job demands–resources: A gender perspective on employee well-being and resilience in retail stores in China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Taris, T.W.; Schreurs, P.J.G.; Schafeuli, W.B. A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2003, 10, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheung, F.M. The role of work-family role integration in a job demands-resources model among Chinese secondary school teachers. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 18, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, G.K.; Biener, L.; Barnett, R.C. Women and gender in research on work and family stress. Am. Psychol. 1987, 42, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensbock, S.; Jennings, G.; Bailey, J.; Patiar, A. Performing: Hotel room attendants’ employment experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 56, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter Powell, P.; Watson, D. Service unseen: The hotel room attendat at work. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsøyen, L.E.; Mykletun, R.J.; Steiro, T.J. Silenced and invisible: The work-experience of room-attendants in Norwegian hotels. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 9, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Geller, P.; Dunahoo, C. Women’s Coping: Communal Versus Individualistic Orientation. In The Handbook of Work and Health Psychology, 2nd ed.; Schabracq, M.J., Winnubst, J.A.M., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 237–257. ISBN 9780470013403. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G. El Análisis de Datos Cualitativos en Investigación Cualitativa; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanselow, A.; Warhurst, C.; Bernhardt, A.; Dresser, L.; Gautie, J.; Schmitt, J. Working at the wage floor: Hotel room attendants and labor market institutions in Europe and the US. In Low Wage Work in a Wealthy World; Russell Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wiker, S.F. Evaluation of Musculoskeletal Disorder Risk in Hotel Housekeeping Jobs; Department of Industrial Relations: State of California. 2013. Available online: https://www.dir.ca.gov/dosh/doshreg/hotel-housekeeping.ch-and-la-final-report.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Akgunduz, Y. The influence of self-esteem and role stress on job performance in hotel businesses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1082–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. Working in Hotels and Catering, 2nd ed.; International Thomson Business Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hoel, H.; Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.L. The cost of violence/stress at work and the benefits of a violence/stress-free working environment. Geneva Int. Labour Organ. 2001, 1–81. [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain, G.; Chênevert, D. Job demands-resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Kensbock, S.; Bailey, J.; Jennings, G.; Patiar, A. Realizing dignity in housekeeping work: Evidence of five star hotels. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Lykes, M. Gender and Personality: Current Perspectives on Theory and Research; Duke University Press: Durham, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ö.D. An undervalued department or a terra incognita? Hotel housekeeping from the perspectives of executive housekeepers and room attendants. Tourism 2017, 65, 450–461. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, E. The Occupational Safety and Health of Cleaning Workers; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work; EU-OSHA.; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; ISBN 9789291913015. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofund; EU-OSHA; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Psychosocial Risks in Europe—Prevalence and Strategies for Prevention; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbach, E.; Gordon, E. The World is Ill. Divided; Edunburgh University Press: Edunburgh, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, M. Gender, work orientations and job satisfaction. Work. Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, K.A.; Donohue, S.M.; Heywood, J.S. Job satisfaction and gender segregation. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2005, 57, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messing, K.; Punnett, Ã.L.; Bond, M.; Alexanderson, K.; Pyle, J.; Zahm, S.; Wegman, D.; Stock, S.R.; De Grosbois, S. Be the fairest of them all: Challenges and recommendations for the treatment of gender in occupational health research. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2003, 629, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, S.; Mohanna, D. Mediating role of job stress between work-family conflict, work-leisure conflict, and employees’ perception of service quality in the hotel industry in France. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, L.; Stevenson, M.; Higgins, C. Too much to do, too little time: Role overload and stress in a multi-role environment. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 25, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.; Baruch, G. Women’s involvement in multiple roles and psychological distress. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagqvist, E.; Gådin, K.G.; Nordenmark, M. Work–family conflict and well-being across Europe: The role of gender context. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2004, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich, B.; English, D. For Her Own Good; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, M.S. Counter-planning from the kitchen: For a feminist critique of type. J. Archit. 2018, 23, 1203–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (n = 34) | <30 | 30 to 39 | 40 to 49 | 50–59 | >59 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( = 50 years old, SD = 10) | 5.9% | 5.9% | 23.5% | 52.9% | 11.8% |

| Years working as HH | <10 | 10 to 14 | 15 to 24 | ≥25 | |

| (n = 34) ( = 19.47, SD = 11.5) | 17.6% | 20.6% | 32.4% | 29.4% | |

| Tenure (n = 34) | Permanent 1 | Recurring seasonal contract 2 | Temporary 3 | ||

| 2.9% | 88.2% | 8.8% | |||

| Hotel category (n = 33) | 2 * | 3 * | 4 * | 5 * | |

| 6.1% | 45.5% | 42.4% | 6.1% | ||

| Code | Key-Informant Profile |

|---|---|

| HHi1 | HH belonging to a union |

| HHi2 | HH belonging to a union |

| HHi3 | HH belonging to a HH’s association |

| HHi4 | HH belonging to a HH’s association |

| SUP | HH’s supervisor |

| GP | General practitioner in a coastal practice |

| PInsp | Physician in governmental inspection service |

| HRDir | Director of human resources (HR) in a hotel chain |

| Prev | Head of the occupational risk prevention service in a hotel chain |

| OHealth | Head of occupational health department in a hotel chain |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chela-Alvarez, X.; Bulilete, O.; García-Buades, M.E.; Ferrer-Perez, V.A.; Llobera-Canaves, J. Perceived Factors of Stress and Its Outcomes among Hotel Housekeepers in the Balearic Islands: A Qualitative Approach from a Gender Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010052

Chela-Alvarez X, Bulilete O, García-Buades ME, Ferrer-Perez VA, Llobera-Canaves J. Perceived Factors of Stress and Its Outcomes among Hotel Housekeepers in the Balearic Islands: A Qualitative Approach from a Gender Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleChela-Alvarez, Xenia, Oana Bulilete, M. Esther García-Buades, Victoria A. Ferrer-Perez, and Joan Llobera-Canaves. 2021. "Perceived Factors of Stress and Its Outcomes among Hotel Housekeepers in the Balearic Islands: A Qualitative Approach from a Gender Perspective" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010052

APA StyleChela-Alvarez, X., Bulilete, O., García-Buades, M. E., Ferrer-Perez, V. A., & Llobera-Canaves, J. (2021). Perceived Factors of Stress and Its Outcomes among Hotel Housekeepers in the Balearic Islands: A Qualitative Approach from a Gender Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010052