1. Introduction

China has experienced dramatic industrialization and economic development over the last three decades. Therefore, over the last three decades, small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have played an essential role in industrialization and economic development because they provide about eighty percent of jobs in China [

1]. However, compared to the corporate sector, small- and medium-sized enterprises generally have low wages and a high level of toxic workplace environments because of despotic leadership [

2]. Since low wages and a toxic workplace environment demotivate the employees, which affects their job satisfaction, many prior studies have found that despotic leadership in SMEs negatively impacts employees’ job satisfaction [

3,

4,

5].

In the era of the knowledge economy, whether or not to create a working environment that stimulates employee potential is a key factor for whether enterprises remain competitive [

6,

7]. Moreover, in Eastern countries where the “rule by man” culture prevails, leadership style, as an important working environment factor, has a particularly prominent influence on employees [

8]. On the positive side, charismatic leaders are like a fountain of sunshine to employees. Conversely, despotic leadership can lead employees towards destruction [

9,

10]. Thus, in terms of talent motivation, “the success or failure of the affair is all due to the leadership.”

The relevant research on leadership covers a broad discussion on the positive influence of leadership on employee motivation [

11]. According to these studies, leadership has a significant impact on employees’ long-term career growth and development, as well as their current work, psychological state, and behavioral performance [

12]. Furthermore, numerous scholars have also performed rich explorations of the positive effects of leadership style (such as transformational, intelligent, and charismatic leadership) on employees. They confirm that leadership style plays a positive role in promoting employee creativity (Herrmann and Felfe [

13]), forming a sense of belonging and organizational commitment Top, Akdere [

14] and improving their work efficiency [

15]. However, due to the influence of traditional culture, employees in Eastern countries tend to adopt a tolerant and silent attitude towards despotic leadership behaviors such as control and suppression. Therefore, relevant investigations on leadership have been in a state of “reporting good news but not bad news” for a long time. Therefore, how does a negative leadership style affect employees’ job satisfaction? There is still a lack of in-depth discussion in the existing literature.

With the spread of information and culture change, employees increasingly affected by negative leadership styles are no longer silent. They bravely express their dissatisfaction with “bad leaders” by leaving their jobs or exposing their leaders. Driven by these phenomena, the dark and destructive sides of leadership behavior have gradually attracted the attention of relevant scholars [

16,

17]. Given the significant impact of destructive leadership behavior on corporate culture, organizations, and individuals, and the fact that relevant data have become increasingly accessible, the relevant empirical studies show an increasing trend [

18]. Despotic leadership, which emphasizes the absolute authority of the leader and requires the absolute obedience of subordinates, is a representative type among all destructive leadership behaviors [

19]. Moreover, this type of leadership is ubiquitous in business organizations in the Oriental and Asia-Pacific cultural contexts, and thus, it is of great research value [

8]. However, due to its negative effects on leadership, despotic leadership research is particularly limited, and the recent findings in the literature are insufficient to provide a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the specific path through which it affects employee job satisfaction and the prevention mechanism of related negative effects [

19]. Moreover, the current literature cannot provide companies and employees with effective guidance and inspiration in dealing with the negative effects of despotic leadership.

There are some gaps in the current literature regarding providing guidance and inspiration for employees to cope with the negative effects of despotic leadership [

8]. Despite the strong interest among researchers and practitioners, some gaps remain in establishing the interrelationship of despotic leadership and job satisfaction. First, most of the research focused on the positive side of leadership, and few researchers were concentrated on the negative effects of despotic leadership. In particular, this is the first study in which we test the negative aspects of despotic leadership and its relationship with job satisfaction, particularly in emerging countries such as China. Second, the despotic leadership practices in SME organizations are not a major focus of the literature. Third, few studies have examined the direct relationship between despotic leadership and job satisfaction or between despotic leadership and leader–member exchange, but the four-way relationship between despotic leadership, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction is unexplored. In particular, studies have not considered self-efficacy as an intervening construct or leader–member exchange as a moderating construct between despotic leadership and job satisfaction.

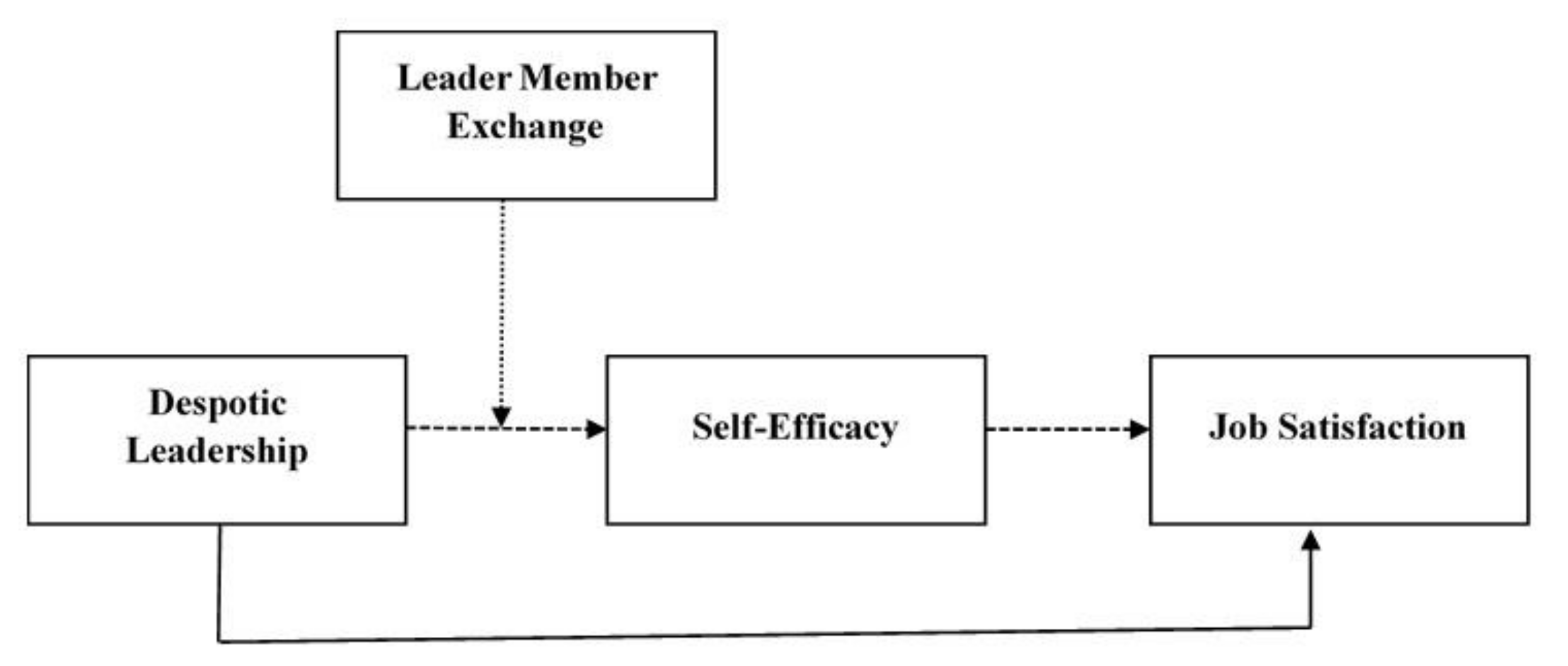

Based on the abovementioned research impetus, the purpose of this study is to analyze the gaps between the relationships of despotic leadership, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. On the basis of the above discussion, the following three research questions are addressed:

RQ1: Does despotic leadership harm the employees’ job satisfaction?

RQ2: How does leader–member exchange moderate the relationship between despotic leadership and self-efficacy?

RQ3: How does self-efficacy intervene between despotic leadership and employee job satisfaction?

The paper is structured as follows: the second part presents the literature about despotic leadership, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. The third section presents the hypothesis development, and the fourth part of this study is about the research methodology. The fifth part of this study presents the discussion. The last section presents the conclusion and limitations.

6. Discussion

Prior studies on leadership have discussed the bright side of leadership style. In this study, we have discussed the dark side of leadership, which shows the impact of despotic leadership on job satisfaction. Despotic leadership is a negative leadership style that affects employees’ job performance. Moreover, this study also expressed the mediating role of self-efficacy between the relationship of despotic leadership and job satisfaction. Similarly, the leader–member exchange is moderating in the relationship between despotic leadership and self-efficacy.

First, we focused on the direct relationship between despotic leadership and employee job satisfaction. The results showed that despotic leadership has a negative impact on employees’ job satisfaction, which supported H1. The findings of this study were also supported by the previous studies [

75,

76]. Similarly, Ofori [

77] conducted a study on the relationship between despotic leadership and employees’ outcomes, the finding of his study indicated that despotic leadership negatively affects employees’ job satisfaction. This study was also supported by the social learning and social exchange theory [

78]. However, in order to maintain the image of leaders and display the advantages of power, despotic leaders often show a strict and autocratic side to their employees, which makes employees feel unhappy, which, in turn, affects their performance [

24]. Kasi and Bibi [

79] demonstrated that a despotic leader will destroy the fair atmosphere of an organization, and they tend to promote those individuals who are ingratiatory, rather than appointing individuals according to their ability [

8]. Therefore, the above studies indicated that despotic leaders negatively affect the job satisfaction among employees, which supports our findings.

Second, the findings of this study confirmed that self-efficacy plays a mediating role between despotic leadership and employee job satisfaction. Therefore, the outcomes are consistent with previous studies and support H2. This result is also in line with the social learning theory [

80]. Naseer and Raja [

5] indicate that despotic leaders were not encouraging towards their subordinates, in addition to such kind of leaders being used to punishing their employees according to their mood. Therefore, it is difficult for the employees to show their talents and gain a sense of self-efficacy from their previous experiences. However, despotic leadership negatively affects self-efficacy in results, and affects the employee’s job satisfaction [

81].

Third, we tested the moderating effect of LMX between despotic leadership and self-efficacy. The findings of this study demonstrated that LMX moderates between despotic leadership and self-efficacy, which supports H3. Therefore, the results of this study also confirm that LMX reduces the negative impact of despotic leadership on employees’ self-efficacy. These results are in line with the theory of social exchange and the research of De Clercq and Fatima [

8]. The hypothesized relationship-moderating effects between despotic leadership and self-efficacy are based on leader–member exchange theory [

82], which supports our findings. Moreover, with the high quality of LMX, the insider will continue to perceive the leader’s recognition and tolerance for their uniqueness in their work. In return for these gifts from the leaders, they tend to be more diligent and positive in their work, and thus have a stronger sense of self-efficacy. On the contrary, in the case of low-quality LMX, outsiders tend to obtain fewer resources and opportunities, and it is difficult for them to get recognition, even for their achievements. As a result, their self-confidence and motivation for progress are, inevitably, gradually lost, and their sense of self-efficacy is lowered [

52].

In this study, we considered two control variables, age and position. The t-test and ANOVA were tested to measure whether an employee’s position influences their self-efficacy and job satisfaction. The findings of this study confirmed that grassroots staff had a higher level of self-efficacy and job satisfaction compared to middle-level managers, and middle-level managers had higher SE and JS than top-level senior management. Moreover, in this study, the authors applied ANOVA to measure the differences in self-efficacy and job satisfaction for different age groups. The outcomes of this study confirmed that the 30 years of age or less group had a higher level of self-efficacy and job satisfaction than the 30–40 years of age group. Similarly, the 30–40 years of age group had higher SE and JS than the 41–49 years of age group, and the 41–49 years of age group had a higher level of SE and JS than the 50 years of age or above group.

7. Conclusions

The outcomes of this study show the relationships between despotic leadership, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. Specifically, despotic leadership has a direct negative impact on job satisfaction, while self-efficacy acts as a mediating role between despotic leadership and job satisfaction. Similarly, the leader–member exchange is moderating in the relationship between despotic leadership and self-efficacy.

The conclusions of this paper are as follows: first, despotic leadership will have a harmful effect on the majority of employees in the organization, and it will be difficult for employees to achieve ideal job satisfaction under such a leader. Secondly, despotic leadership damages employees’ job satisfaction through the reduction of their self-efficacy. Despotic leaders are often overconfident and autocratic, which makes them less able to encourage or empower employees. Therefore, employees cannot gain self-efficacy from successful experience and the recognition others, and are thus less able to get satisfaction from their work. Finally, when encountering despotic leaders, employees can establish appropriate personal relationships with the leader to reduce the negative impact of despotic leadership on their self-efficacy and job satisfaction.

8. Contributions, Limitations, and Future Research

8.1. Theoretical Contribution

First, from the employees’ perspective, this work deepens the negative impact of despotic leadership. Given the limitation of data availability, early research on leadership mainly focused on the positive impact of leadership on enterprises and employees, and investigations on negative leadership styles are rare [

8]. As a destructive leadership style prevalent in Eastern cultures, despotic leadership has long had a wide impact on the employees of SMEs, but only in recent years has it gradually attracted the attention of researchers [

5]. At present, the existing literature primarily concentrates on the overall impact of despotic leadership on the organization, and rarely goes deep into the micro-level of employees to explore the micro-impact of this leadership style on employees’ psychology and work experience [

19,

83]. Based on the social learning theory by Walker and Morley [

80], this study proposes an empirical model whereby despotic leadership reduces job satisfaction by influencing employee self-efficacy. According to the test results, despotic leadership’s strong controlling desire will lead to “learned helplessness” from the employees, a circumstance that will cause the loss of their self-efficacy and, ultimately, the perceived significance of their work. These findings broaden the academic understanding of the mechanism of despotic leadership and enrich the research context of social learning theory.

Second, from the perspective of social exchange, this work explores the coping mechanisms of the negative effects of despotic leadership. In the previous literature, few studies have examined the direct relationship between despotic leadership and job satisfaction or between despotic leadership and leader–member exchange, but the four-way relationship between despotic leadership, leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction has been, for the first time, explored in this study. In particular, this study considered self-efficacy as an intervening construct and leader–member exchange as a moderating construct between despotic leadership and job satisfaction. According to the empirical test results, we posit that LMX can enhance the trust and emotion of leaders toward employees to provide more empowerment and support to the latter. The empowerment and support of leaders can better promote employee self-efficacy. Thus, the leader–member exchange can weaken the negative impact of despotic leadership on employee self-efficacy. These findings provide strategic guidance for employees to deal with despotic leadership and further confirm the practical value of social exchange theory.

8.2. Practical Implications

First, the employees of SMEs should acknowledge the negative effects of despotic leadership and take personality and leadership style as important reference standards in the recruitment and selection of managers so as to maximally prevent leaders with a strong despotic style from joining the management. Second, enterprises must formulate strict and fair rules and regulations to help employees establish correct work values to prevent an unhealthy atmosphere of pursuing individual authority and autocracy within the enterprise, and prohibit the emergence of “small groups” in an effort to improve employee job satisfaction and work efficiency. Finally, from the employees’ perspective, they should take the initiative to maintain a good relationship with despotic leaders, should they appear. According to the theory of social exchange, “insiders” are more likely to be valued by despotic leaders, thereby gaining richer resources and opportunities. Even if they make mistakes, “insiders” are more likely to be forgiven and tolerated by leaders and have higher satisfaction with their jobs. Regardless of the leadership style, employees should pay attention to maintaining a certain connection with the leader and strive to maintain the authority of the leader in the process of work. Of course, if employees find that they do not get along with their supervisor, they should “flee” as soon as possible to prevent loss.

8.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has some limitations, which should be considered when interpreting the results. This study was cross-sectional, and as such, does not provide inference on causality. Like many prior studies, the study used a self-reporting technique, which may be subjected to social desirability bias. Secondly, the findings of this study only investigated small- and medium-sized enterprises. Further research can be undertaken in the IT, education, or manufacturing sectors. It generalized the outcomes and modified the concepts. Thirdly, given the lack of research resources and limited availability, this study only examined the issue from the perspective of subordinates, and did not conduct a matching survey on subordinates and their leaders. Moreover, this work used a cross-sectional approach, and only focused on the psychological state of employees at a given time, a circumstance that may lead to the problem of common method deviation. Although the data analysis found no serious common method deviation, future research will benefit from collecting data from multiple time points for comparison and reference and dynamically examining employees’ work experience.