“Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

What is the role of group cohesion in CBT groups for anxiety and depression? Is group cohesion experienced differently by patients in mixed-diagnoses versus same-diagnosis groups? And if so, how?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context: TRACT-RCT

2.2. Outpatient Treatments in Danish MHS

2.3. Participants

- TCBT—Unified Protocol (UP) for MDD, agoraphobia, panic disorder and social phobia mixed group

- CBT depression for MDD

- CBT social anxiety for social anxiety disorder

- CBT panic for panic disorder and agoraphobia

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

- All of the transcripts were read thoroughly in order for the first author to familiarize herself with the data.

- Two full transcripts were coded on a sentence-to-sentence basis by the first author and the second author separately.

- The first and second author held a meeting in which they went over every single code, discussing and debating in order to reach consensus if any discrepancies were present.

- Step 2 + 3 were repeated twice, meaning that 6 full transcripts were consensus coded (26%), on the sixth interview, only 5 codes differed between the coders, indicating very high consensus in the coding. The first author coded the remaining transcripts.

- A list of group cohesion-related codes was created, and all of the material labelled with those codes was extracted from the full dataset. The group cohesion-related quotes were chosen by going through the coding set and, firstly, choosing all the codes that had the word ‘group’ in it, i.e., group dynamics, the group, group members etc. Secondly, ABC went through all remaining codes and read the related material; all codes that had group-related content were included, i.e., the breaks, normalization and similarities and differences.

- The codes were revisited in the search for overarching themes. An inductive approach was taken, meaning that no theory was driving the process.

- The dataset was divided into two: (a) the data belonging to patients who had been in diagnosis-specific groups and (b) the patients who had been in mixed-diagnoses groups. This was completed in order to detect if there were differences between the groups within each theme.

- Themes were named and the model of the group cohesion process was defined.

3. Results

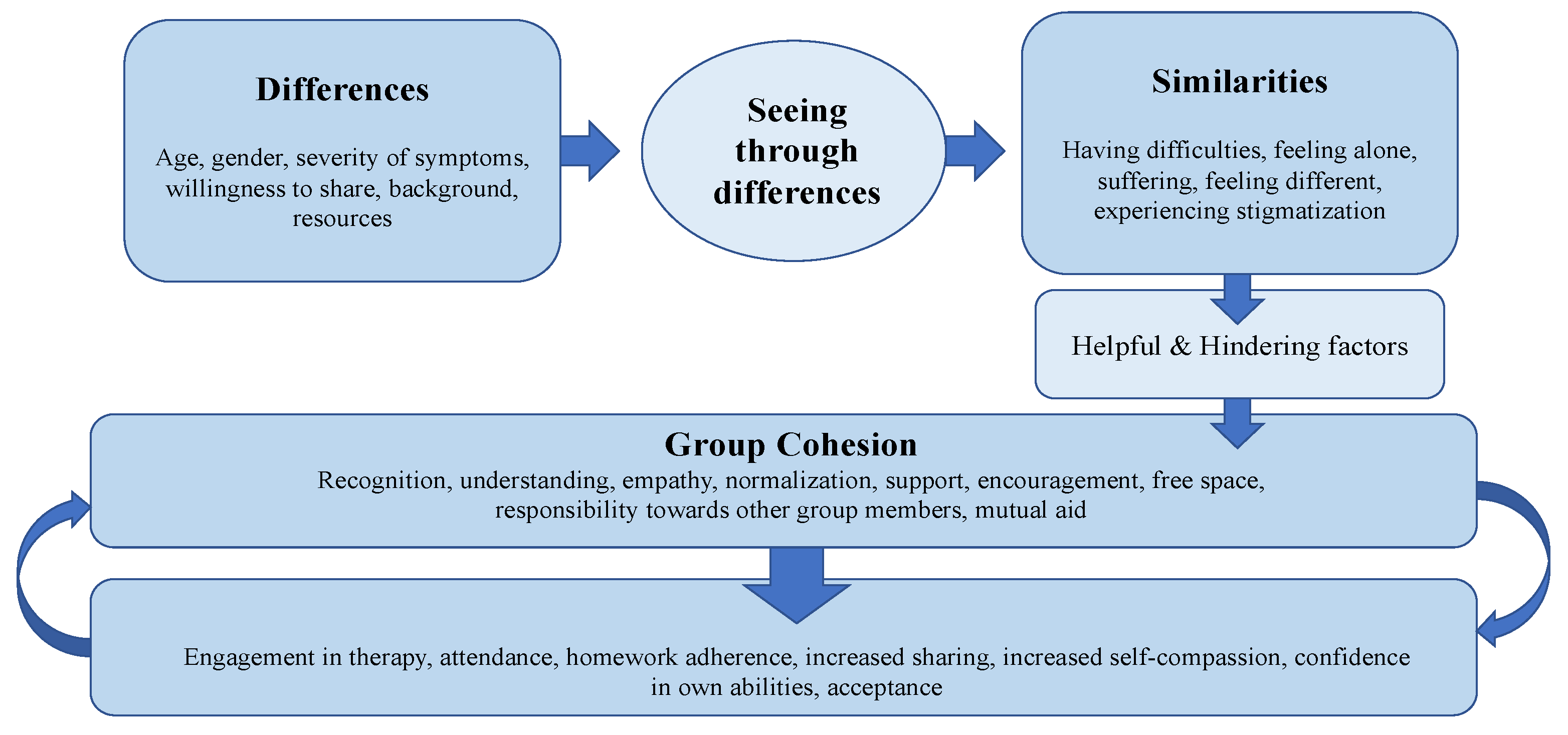

3.1. Theme 1: From Differences to Similarities

- I:

- How did you experience the other group members?

- Caroline, UP group:

- Well, we were at different places in life. Some had not yet started education. Some of us had been on the labour market for many years. Some could not work and had tried to get early retirement. So, we were a very mixed group. And then we were only women... but our group worked. Despite all these differences. Because it was not those differences in our private lives, in that way, that was the reason why we were here. We just had, many of us, the same symptoms… and fundamentally for most of us, those were about the same things.

- I:

- How did you experience the other group members?

- Cecilia, Panic-disorder group:

- It was very varied, in terms of, how burdened they were by their symptoms, I think. And that was actually pretty positive, that we weren’t all equally well or unwell. Because, then you could say, that you can kind of put yourself into perspective in relation to them, like ‘that person is that well and that person has come that far’, I mean not in a negative way, but, more... like it gave a sense of lifting each other up, and that you could each see positive things in the others, so you got a sense that ‘oh well then I can also do it’ (...) There were probably more differences than similarities. Because there was differences in terms of ehm... Well, age, gender and where people where on all levels, it seemed. But it wasn’t something I had really thought that much about (...) again, I think it is positive, because you can put it all into perspective and it gives you a feeling that ‘oh well we are not just all the same’ but ehm... it’s all kinds of people, who feels this way in each their way, and yeah, I thought that was positive.

- Katrine, UP group:

- It was a really good group. We have agreed, that we will meet up in two weeks time, in order to keep it maintained… or to support one another. I mean, we were wildly different all of us. I mean, really wildly different and different ages and did completely different things and also had different diagnoses, but we worked pretty well together.

- I:

- Yes?

- Katrine, UP group:

- I mean, we could recognise ourselves in each other and in the problems that we have had, even across diagnoses.

- I:

- So it wasn’t something that stood in the way?

- Katrine, UP group:

- Not at all.

- Karen, UP-group:

- At one point, one of the others was like ‘why do I have to sit with those who have anxiety? I have a depression’ and I had both diagnoses and some only had the anxiety diagnosis… and all of a sudden it occurred to her, that the things that I said, when I described how the anxiety affected me, then she said ‘that is exactly how I feel and God, that is the same. And that’s when we figured, that, that is why they are trying to put these two things together in the treatment, because it is so similar in structure. And that’s when it suddenly occurred to her, I think it was the fifth or sixth session, when she saw the light, like ‘wow, it is the same’.

3.2. Theme 2: The Role of Cohesion in Group CBT

- Sara, Depression group:

- It gave me, how do I explain it? You feel like you are all alone in the world somehow, prior to coming. And I found that difficult. I mean... it feels like a taboo, when you speak to others, friends as well... When you speak to friends, there isn’t really anyone to mirror yourself in. So, when you start in this group, even though I was one of the youngest, it was still really nice to have these people here to mirror yourself through. And we could talk together, and we were in the same place. And knew the problems, even though the causes were different. And I found that incredibly comforting. I thought it was great and it gave me a lot, this thing about mirroring yourself in someone else. Even though it is negative, it is just really nice to know that you are not all alone in it.

- Eva, UP group:

- In the beginning, we were all insecure. But they were engaged and worked as much on it as I did. There was a will to want this. The youngest was 21 and I am 52 and I thought ‘wow do we have anything in common?’ It didn’t feel unnatural despite that. And many of them were students or academics and I am a musician. And have, of course, sometimes a different understanding of the world. It is interesting to hear what kind of things you can be battling. We had different problems, but basically, anxiety and depression and so on, it was very similar, but we came with different backgrounds and things that had triggered our problem. The fact that we were doing as poorly as we were meant that we had a lot of practical problems too. When you don’t have peace to just get well. Because there are so many practical things you have to fight. That we had in common, a lot. The system around us. There was a pressure. From outside. We are fighting basic survival stuff.

- Peter, Depression group:

- I had felt very alone in it. Alone with my struggles (prior to beginning in the group). Even though I am not directly comparable with everyone, then... the story is the same, but the details are different. I think, when I was out here in sessions on my own, I felt very alone in it all. But being put in a group also creates group pressure somehow, that makes it easier to get homework and tasks done, I would say.

- I:

- Because?

- Peter, Depression group:

- Because, then there is a whole group you can disappoint all of a sudden. And that is kind of positive. A little bit of peer pressure. Whatever works, you know?

- I:

- Okay, and being together about it, not being alone, how does that impact you?

- Peter, Depression group:

- It does a lot for your sense of self-worth. Seeing that it is normal, that other people fight it too. I am not a uniquely bad human being. There are tons of people who feel this way, and they are not bad people, therefore... and so on. I think about it as in, your shoes become less heavy, it is like there are springs in your step when you walk. That you are no longer dragging yourself, all the time.

3.3. Theme 3: Factors Helpful and Hindering to Group Cohesion

- Tina, UP group:

- We had a lot of the same ways of thinking and ways of seeing the world. We were all there because we had some problems that we couldn’t solve on our own, and we wanted help and we had a wish for things to get better. We wanted to work and make things better. I feel like that really tied us together.

- Jonathan, Depression group:

- The biggest help... has actually perhaps been, even though I didn’t say that much, just meeting the other and hearing about and listening to their stories. I think, the breaks were the biggest help. It was a joy to meet likeminded people.

- Peter, Depression group:

- There was especially one person, that I am thinking of now, who weren’t really there. Or who was very shy or holding back, had a lot of barriers. I actually felt like it was hindering to creating an optimal good dynamic. I do think the Clara (the therapist) was really good, even though this person didn’t say anything, she kept making openings for the person... and it took the time it took, but I feel like, when she did that, it helped a lot on the dynamic, when everyone shared, it was easier to share more. At least it made it feel safer. That there wasn’t a stranger in the corner who didn’t say anything.

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flückiger, C.; Del Re, A.C.; Wampold, B.E.; Horvath, A.O. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychother 2018, 55, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivlighan, D.M., Jr.; Holmes, S.E. The importance of therapeutic factors: A typology of therapeutic factor studies. In Handbook of Group Counselling and Psychotherapy; DeLucia-Waack, J.L., Kalonder, C.R., Riva, M.T., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, G.; Fuhriman, A.; Johnson, J. Cohesion in group psychotherapy. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2001, 38, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalom, I.D. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy; Basic Books (AZ): New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudiano, B.A. Cognitive-behavioural therapies: Achievements and challenges. Évid. Based Ment. Heal. 2008, 11, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube-Schiff, M.; Suvak, M.K.; Antony, M.M.; Bieling, P.J.; McCabe, R.E. Group cohesion in cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, G.M.; McClendon, D.T.; Yang, C. Cohesion in group therapy: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marziali, E.; Munroe-Blum, H.; McCleary, L. The Contribution of Group Cohesion and Group Alliance to the Outcome of Group Psychotherapy. Int. J. Group Psychother. 1997, 47, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andel, P.; Erdman, R.A.; Karsdorp, P.A.; Appels, A.; Trijsburg, R.W. Group Cohesion and Working Alliance: Prediction of Treatment Outcome in Cardiac Patients Receiving Cognitive Behavioral Group Psychotherapy. Psychother. Psychosom. 2003, 72, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinger, U.; Schauenburg, H. Effects of individual cohesion and patient interpersonal style on outcome in psychodynamically oriented inpatient group psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2010, 20, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, T.P.; McAlinden, N.M. Changes in quality of life following group CBT for anxiety and depression in a psychiatric outpatient clinic. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E. Cohesion in Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy for Anxiety Disorders and Major Depression. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2010, 60, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, T.P.; Bullbeck, K.; Campbell, J.M. Cognitive change process during group cognitive behaviour therapy for depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 92, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, N.K.; Rohde, P.; Seeley, J.R.; Clarke, G.N.; Stice, E. Potential Mediators of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adolescents With Comorbid Major Depression and Conduct Disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hand, I.; Lamontagne, Y.; Marks, I.M. Group Exposure (Flooding) in vivo for Agoraphobics. Br. J. Psychiatry 1974, 124, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, P.J. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Transdiagnostic CBT for Anxiety Disorder by Comparison to Relaxation Training. Behav. Ther. 2012, 43, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, D.H.; Farchione, T.J.; Bullis, J.R.; Gallagher, M.W.; Murray-Latin, H.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Cassiello-Robbins, C. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Therapist Guide; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reinholt, N.; Hvenegaard, M.; Bryde Christensen, A.; Eskildsen, A.; Hjorthøj, C.; Poulsen, S.; Arendt, M.B.; Rosenberg, N.K.; Gryesten, J.R.; Christensen, C.W.; et al. Transdiagnostic versus Diagnosis-specific Group Cognitive-behavioral Therapy for Anxiety Disorder and Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, P.J.; McCabe, R.E.; Anthony, M.M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Groups; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, J. Qualitative Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bullis, J.R.; Boettcher, H.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Farchione, T.J.; Barlow, D.H. What is an emotional disorder? A transdiagnostic mechanistic definition with implications for assessment, treatment, and prevention. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2019, 26, e12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilamowska, Z.A.; Fairholme, C.P.; Ellard, K.K.; Farchione, T.J.; Barlow, D.H.; Thompson-Hollands, J. Conceptual background, development, and preliminary data from the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2010, 27, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danske Regioner. Pakkeforløb for Angst. 2017. Available online: https://www.regioner.dk/media/5548/pakkeforloeb-for-angst.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfred, S.M.; Aharoni, R.; Hvenegaard, M.; Poulsen, S.; Bach, B.; Arendt, M.; Rosenberg, N.K.; Reinholt, N. Transdiagnostic group CBT vs. standard group CBT for depression, social anxiety disorder and agoraphobia/panic disorder: Study protocol for a pragmatic, multicenter non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberg, S.; Törnkvist, Å.; Andersson, G. Experiences of patients in cognitive behavioural group therapy: A qualitative study of eating disorders. Scand. J. Behav. Ther. 2001, 30, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledhill, A.; Lobban, F.; Sellwood, W. Group cbt for people with schizophrenia: A preliminary evaluation. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1998, 26, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, P.; Stenfert Kroese, B.; Jahoda, A.; Stimpson, A.; Rose, N.; Rose, J.; Willner, P. ‘It’s made all of us bond since that course…’—A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of a CBT anger management group intervention. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, E.; Larkin, M.; Melhuish, R.; Wykes, T. More than just a place to talk: Young people’s experiences of group psychological therapy as an early intervention for auditory hallucinations. Psychol. Psychother. 2007, 80 Pt 1, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, S. De-privatization: Client Experience of Short-term Dynamic Group Psychotherapy. Group 2004, 28, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment Type | Pseudonym | Sex | Age | Primary Diagnosis | Comorbid Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tCBT | Marcus | M | 28 | MDD | - |

| Eva | F | 55 | MDD | - | |

| Niels | M | 35 | MDD | - | |

| Emma | F | 34 | MDD | - | |

| Laura | F | 43 | MDD | - | |

| Katrine | F | 32 | SA | ADHD | |

| Simone | F | 65 | PD | - | |

| Caroline | F | 42 | MDD | - | |

| Karen | F | 53 | MDD | PD, AGO | |

| Tina | F | 25 | PD | AGO | |

| Victoria | F | 54 | PD | AGO, SA MDD, GA | |

| Julie | F | 28 | SA | MDD | |

| CBT | Michael | M | 28 | PD | AGO |

| Josephine | F | 22 | SA | OCD, GA | |

| Simon | M | 54 | MDD | PD | |

| Barbara | F | 31 | PD | AGO | |

| Jonathan | M | 49 | MDD | SA | |

| Peter | M | 41 | MDD | SA | |

| Michelle | F | 26 | MDD | PD | |

| Sara | F | 25 | MDD | - | |

| David | M | 30 | SA | PD | |

| Cecilia | F | 38 | PD | AGO | |

| Kristine | F | 37 | SA | ADHD, GA |

| Topic | Examples of Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Open talk | Tell me about your therapy course, whatever comes to mind. |

| 2. Expectations | What were your expectations prior to starting in the group? Were these expectations met? |

| 3. Group | How did it feel to be in this group? How were the other group members? |

| 4. Important moments | Were there any specific moments from the therapy that you remember especially well? |

| 5. The therapists | How did you find the therapists? Were there any moments with the therapists you remember particularly well? |

| 6. Change | Do you feel different now compared to when you started? If so, how? Why do you think that is? |

| 7. The therapy | What was the biggest help for you? Did anything happen that was negative for you? |

| 8. Manual specific factors | Where there any specific techniques you found especially helpful? |

| 9. The end | Do you feel like I have a good understanding of your experience? Have we missed anything that was important for you? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryde Christensen, A.; Wahrén, S.; Reinholt, N.; Poulsen, S.; Hvenegaard, M.; Simonsen, E.; Arnfred, S. “Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105324

Bryde Christensen A, Wahrén S, Reinholt N, Poulsen S, Hvenegaard M, Simonsen E, Arnfred S. “Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(10):5324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105324

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryde Christensen, Anne, Signe Wahrén, Nina Reinholt, Stig Poulsen, Morten Hvenegaard, Erik Simonsen, and Sidse Arnfred. 2021. "“Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 10: 5324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105324

APA StyleBryde Christensen, A., Wahrén, S., Reinholt, N., Poulsen, S., Hvenegaard, M., Simonsen, E., & Arnfred, S. (2021). “Despite the Differences, We Were All the Same”. Group Cohesion in Diagnosis-Specific and Transdiagnostic CBT Groups for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105324