Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Digitisation of Prisons

1.2. Barriers to the Use of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services for Prisoners

1.3. The Theory of Planned Behaviour as a Perspective for the Introduction of Digital Services

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

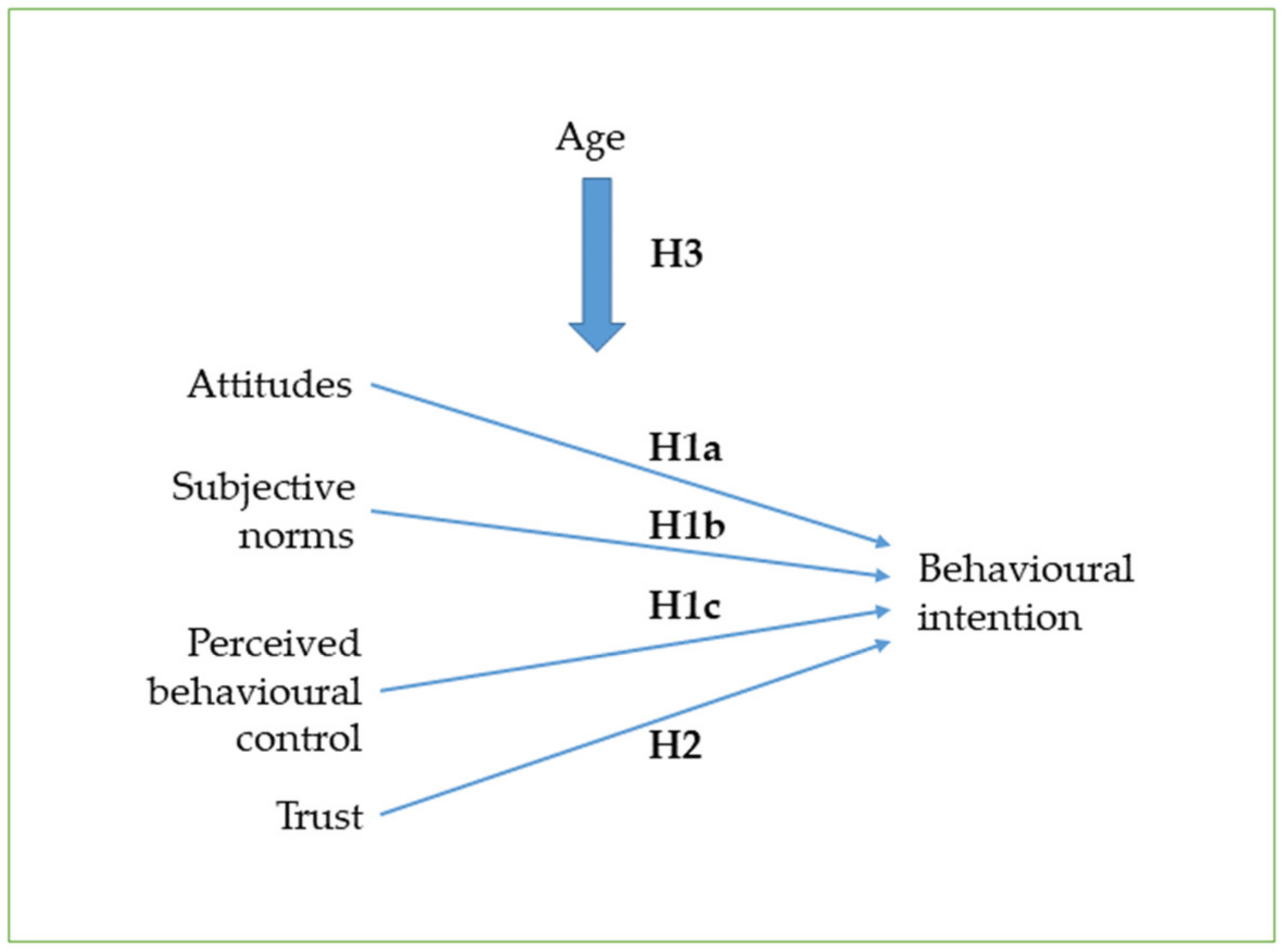

2.2. Aim and Hypotheses

2.3. Sample

2.4. Measures

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents

3.2. The Reliabilities of the Measures

3.3. Intention to Use Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services and Factors That Affect It

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Reflection on the Results

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The statements included in the measures.

- Intention to use digital services

- Perceived behavioural control

- Subjective norms

- Attitudes

- Trust

References

- Joukamaa, M.; Vartiainen, H.; Viitanen, P.; Wuolijoki, T.; Aarnio, J.; von Gruenewaldt, V.; Hakamäki, S.; Hypen, K.; Lauerma, H.; Lintonen, T.; et al. Rikosseuraamusasiakkaiden Terveys, Työkyky ja Hoidontarve [Health, Working Capacity and Need for Treatment of Criminal Sanctions Clients]. Criminal Sanction Agency, Publications 1/2010. 2010. Available online: https://www.rikosseuraamus.fi/material/attachments/rise/julkaisut-risenjulkaisusarja/6AqMACEr8/RISE_1_2010_Rikosseuraamusasiakkaiden_terveys_tyokyky_ja_hoidontarve.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Toreld, E.M.; Haugli, K.O.; Svalastog, A.L. Maintaining normality when serving a prison sentence in the digital society. Croat. Med. J. 2018, 59, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van De Steene, S.; Knight, V. Digital transformation for prisons: Developing a needs-based strategy. Probat. J. 2017, 64, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, V.; Van de Steene, S. The capacity and capability of digital innovation in prisons: Towards smart prisons. Adv. Correct. J. 2017, 4, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Reisdorf, B.C.; Rikard, R.V. Digital rehabilitation: A model of reentry into the digital age. Am. Behav. Sci. 2018, 62, 1273–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya-Ogburu, I.F.; Toyama, K.; Dillahunt, T.R. Towards an effective digital literacy intervention to assist returning citizens with job search. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Barros, R.; Leite, C. Lifelong learning through e-learning in European prisons: Rethinking digital and social inclusion. In Proceedings of the INTED 2015 Conference, Madrid, Spain, 2–4 March 2015; pp. 1038–1046. Available online: https://library.iated.org/view/MONTEIRO2015LIF (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Hatcher, R.; Palmer, E.; Tonkin, M. Evaluation of Digital Technology in Prison. 2020. Available online: https://insidetime.org/download/publications/prison_related/evaluation-digital-technology-prisons-report-July-2020.PDF (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- McDougall, C.; Pearson, D.A.S.; Torgerson, D.J.; Garcia-Reyes, M. The effect of digital technology on prisoner behavior and reoffending a natural stepped-wedge design. J. Exp. Criminol. 2017, 13, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J. Digital Inclusion: An Analysis of Social Disadvantage and the Information Society; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2008; Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/26938 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Helsper, E.J. A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion. Commun. Theory 2012, 22, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barreiro-Gen, M.; Novo-Corti, I. Collaborative learning in environments with restricted access to the internet: Policies to bridge the digital divide and exclusion in prisons through the development of the skills of inmates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 1172–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duwe, G.; McNeeley, S. Just as Good as the Real Thing? The Effects of Prison Video Visitation on Recidivism. Crime Delinq. 2020, 67, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.S. Exploring the Potential of Digital Technology to Reduce Recidivism: A Delphi Study on the Digitalization of Prison Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Ashford University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, June 2020. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/2fa3293795b3971f713d4b288f6aeb93/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=51922&diss=y (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Selwyn, N. Reconsidering political and popular understandings of the digital divide. N. Media Soc. 2004, 6, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A.; Willis, M. Prisoner use of information and communications technology. Trends Issues Crime Crim. Justice 2018, 560, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, V. Some Observations on the Digital Landscape of Prisons Today. Prison Serv. J. 2015, 220, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, H.; Pike, A. Engaging prisoners in education: Reducing risk and recidivism. Adv. Correct. J. Int. Correct. Prison. Assoc. 2016, 1, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Puolakka, P.; Hovila, S. TIC19012—The Development of Digitalization and “Smart Prison” Solutions for Prisoners in Finnish Criminal Sanctions Agency. In Proceedings of the Technology in Corrections Conference: Digital Transformation, Lisbon, Portugal, 2–4 April 2019; Available online: https://icpa.org/library/tic19012-the-development-of-digitalization-and-smart-prison-solutions-for-prisoners-in-finnish-criminal-sanctions-agency/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Mufarreh, A.; Waitkus, J.; Booker, T.A. Prison official perceptions of technology in prison. Punishm. Soc. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Corrections & Prisons Association (ICPA). Grand Opening of Agder Prison—Unit Mandal. 2020. Available online: https://icpa.org/grand-opening-of-agder-prison-unit-mandal/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- PrisonCloud. 2020. Available online: https://www.ebo-enterprises.com/prisoncloud (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Robberechts, J.; Beyens, K. PrisonCloud: The beating heart of the digital prison cell. In The Prison Cell Palgrave Studies in Prisons and Penology; Turner, J., Knight, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, V.; Van De Steene, S. Digitizing the prison: The light and dark future. Prison Serv. J. 2017, 231, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Criminal Sanction Agency. Smart Prison Project. 2019. Available online: https://rikosseuraamus.fi/en/index/topical/projects.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Lindström, B.; Puolakka, P. Smart Prison: The Preliminary Development Process of Digital Self-Services in Finnish Prisons. 2021. Available online: https://icpa.org/smart-prison-the-preliminary-development-process-of-digital-self-services-in-finnish-prisons/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Jewkes, Y.; Reisdorf, B.C.A. Brave new world: The problems and opportunities presented by new media technologies in prisons. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2016, 16, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hustad, E.; Hansen, J.L.; Skaiaa, A.; Vassilakopoulou, P. Digital Inequalities: A review of contributing factors and measures for crossing the divide. In Digital Transformation for a Sustainable Society in the 21st Century, Proceedings of the 18th IFIP WG 6. 11 Conference on E-Business, E-Services, and E-Society, I3E 2019, Trondheim, Norway, 18–20 September 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Pappas, I., Mikalef, P., Dwivedi, Y., Jaccheri, L., Krogstie, J., Mäntymäki, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisdorf, B.C.; Jewkes, Y. (B)Locked sites: Cases of Internet use in three British prisons. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järveläinen, E.; Rantanen, T. Incarcerated people’s challenges for digital inclusion in Finnish prisons. Nord. J. Criminol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, E.J.; Hatcher, R.M.; Tonkin, M.J. Evaluation of Digital Technology in Prisons. 2020. Ministry of Justice Analytical Series. Available online: http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/research-and-analysis/moj (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Lockitt, W. Technology in Prisons. 2011. Available online: http://www.wcmt.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrated-reports/797_1.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Helsper, E.J.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M. Do the rich get digitally richer? Quantity and quality of support for digital engagement. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Courtois, C.; Verdegem, P. With a little help from my friends: An analysis of the role of social support in digital inequalities. N. Media Soc. 2016, 18, 1508–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robberechts, J. Digital Privacy Behind Bars. Prison Serv. J. 2020, 248, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kouvo, A.; Saari, J. Vankien luottamussuhteet [Prisoners’ trusted relationships]. In Suomalainen Vanki Arjen Rakenteet ja Elämänlaatu Vankilassa; Kainulainen, S., Saari, J., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2021; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, P.Y.K.; Hu, P.J.H. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A Model comparison approach. Decis. Sci. 2001, 32, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.J.; Karsh, B.T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Its past and its future in health care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rawstorne, P.; Jayasuriya, R.; Caputi, P. Issues in Predicting and Explaining Usage Behaviors with the Technology Acceptance Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior When Usage Is Mandatory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2000 Proceedings, Brisbane, Australia, 10–13 December 2000; p. 5. Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2000/5 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.M.; Prentice, G.R.; McLaughlin, C.G. Prisoner intentions to participate in an electronic monitoring scheme: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Crim. Psychol. 2013, 3, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.K.; Hu, P.J.H. Examining a model of information technology acceptance by individual professionals: An exploratory study. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2002, 18, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Krogstiea, J.; Siaub, K. Developing an instrument to measure the adoption of mobile services. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2011, 7, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ni, Q.; Zhou, R. What factors influence the mobile health service adoption? A meta-analysis and the moderating role of age. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2018, 43, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Han, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, C.; Reinhardt, J.D. Factors influencing the adoption of online health consultation services: The role of subjective norm, trust, perceived benefit, and offline habit. Front. Public Health 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, L.; Bélanger, F. The utilization of e-government services: Citizen trust, innovation and acceptance factors. Inf. Syst. J. 2005, 15, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Barraket, J.; Wilson, C.K.; Cook, K.; Louie, Y.M.; Holcombe-James, I.; Ewing, S.; MacDonald, T. Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia; Telstra: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.K.; Thomas, J.; Barraket, J. Measuring Digital Inequality in Australia: The Australian Digital Inclusion Index. J. Telecommun. Digit. Econ. 2019, 7, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Criminal Sanction Agency. Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://www.rikosseuraamus.fi/material/attachments/rise/julkaisut-tilastollinenvuosikirja/pjeawUKaf/Statistical_Yearbook_2019_of_the_Criminal_Sanctions_Agency.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Boduszek, D.; Adamson, G.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Bourke, A. The role of criminal social identity in the relationship between criminal friends and criminal thinking style within a sample of recidivistic prisoners. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2013, 23, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Items | N | Mean | SD | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to use digital services | 5 | 221 | 3.40 | 1.03 | 0.866 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 5 | 221 | 3.69 | 1.04 | 0.908 |

| Subjective norms | 4 | 219 | 3.53 | 0.92 | 0.832 |

| Attitudes | 3 | 221 | 3.98 | 0.99 | 0.803 |

| Trust | 7 | 222 | 3.37 | 1.12 | 0.967 |

| Age | 1 | 193 | 37.8 | 11.7 | - |

| Statements | N | I Totally Disagree (%) | I Partially Disagree (%) | I Neither Agree nor Disagree (%) | I Partially Agree (%) | I Totally Agree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I will use digital social and health services whenever possible in the future. | 223 | 7.2 | 5.8 | 24.7 | 31.4 | 30.9 |

| I am likely to primarily deal with social and health services in electronic form in the future. | 222 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 23.0 | 28.8 | 32.0 |

| When I need to talk to a professional in the future, I will prefer to meet remotely rather than face to face, if at all possible. | 223 | 28.7 | 13.9 | 27.4 | 15.7 | 14.3 |

| I want to manage matters related to my social benefits via the Internet in the future. | 222 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 25.2 | 23.4 | 34.7 |

| I would like to primarily take care my health-related issues via the Internet in the future. | 223 | 15.7 | 13.9 | 30.9 | 18.8 | 20.6 |

| Variable | Intention to Use Digital Services | Perceived Behavioural Control | Subjective Norms | Attitudes | Trust | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention to use digital services | 1 | |||||

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.712 p < 0.001 N = 219 | 1 | ||||

| Subjective norms | 0.696 p < 0.001 N = 219 | 0.485 p < 0.001 N = 217 | 1 | |||

| Attitudes | 0.493 p < 0.001 N = 217 | 0.444 p < 0.001 N = 217 | 0.365 p < 0.001 N = 216 | 1 | ||

| Trust | 0.643 p < 0.001 N = 219 | 0.539 p < 0.001 N = 218 | 0.565 p < 0.001 N = 217 | 0.379 p < 0.001 N = 218 | 1 | |

| Age | −0.093 p = 0.201 N = 191 | −0.261 p < 0.001 N = 191 | −0.072 p = 0.322 N = 189 | −0.128 p = 0.080 N = 189 | −0.120 p = 0.096 N = 192 | 1 |

| Model 11 | ||||||

| Independent Variable | B | SE | Beta | t | p | VIF |

| (constant) | −0.938 | 0.346 | − | −2.707 | 0.008 | − |

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.326 | 0.063 | 0.335 | 5.154 | <0.001 | 1.599 |

| Subjective norms | 0.443 | 0.068 | 0.403 | 6.524 | <0.001 | 1.441 |

| Attitudes | 0.166 | 0.062 | 0.153 | 2.656 | 0.009 | 1.262 |

| Trust | 0.196 | 0.061 | 0.217 | 3.246 | 0.001 | 1.690 |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.033 | 0.521 | 0.603 | 1.489 |

| Marital status | −0.032 | 0.113 | −0.015 | −0.281 | 0.780 | 1.088 |

| Education level | 0.135 | 0.109 | 0.069 | 1.230 | 0.221 | 1.201 |

| Number of convictions | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.785 | 0.434 | 1.234 |

| Model 22 | ||||||

| Independent Variable | B | SE | Beta | t | p | VIF |

| (constant) | −0.547 | 0.198 | − | −2.763 | 0.006 | − |

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.368 | 0.048 | 0.374 | 7.700 | <0.001 | 1.650 |

| Subjective norms | 0.423 | 0.054 | 0.375 | 7.816 | <0.001 | 1.606 |

| Attitudes | 0.139 | 0.047 | 0.128 | 2.960 | 0.003 | 1.319 |

| Trust | 0.161 | 0.046 | 0.174 | 3.515 | 0.001 | 1.720 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rantanen, T.; Järveläinen, E.; Leppälahti, T. Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115528

Rantanen T, Järveläinen E, Leppälahti T. Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115528

Chicago/Turabian StyleRantanen, Teemu, Eeva Järveläinen, and Teppo Leppälahti. 2021. "Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115528

APA StyleRantanen, T., Järveläinen, E., & Leppälahti, T. (2021). Prisoners as Users of Digital Health Care and Social Welfare Services: A Finnish Attitude Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5528. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115528