Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

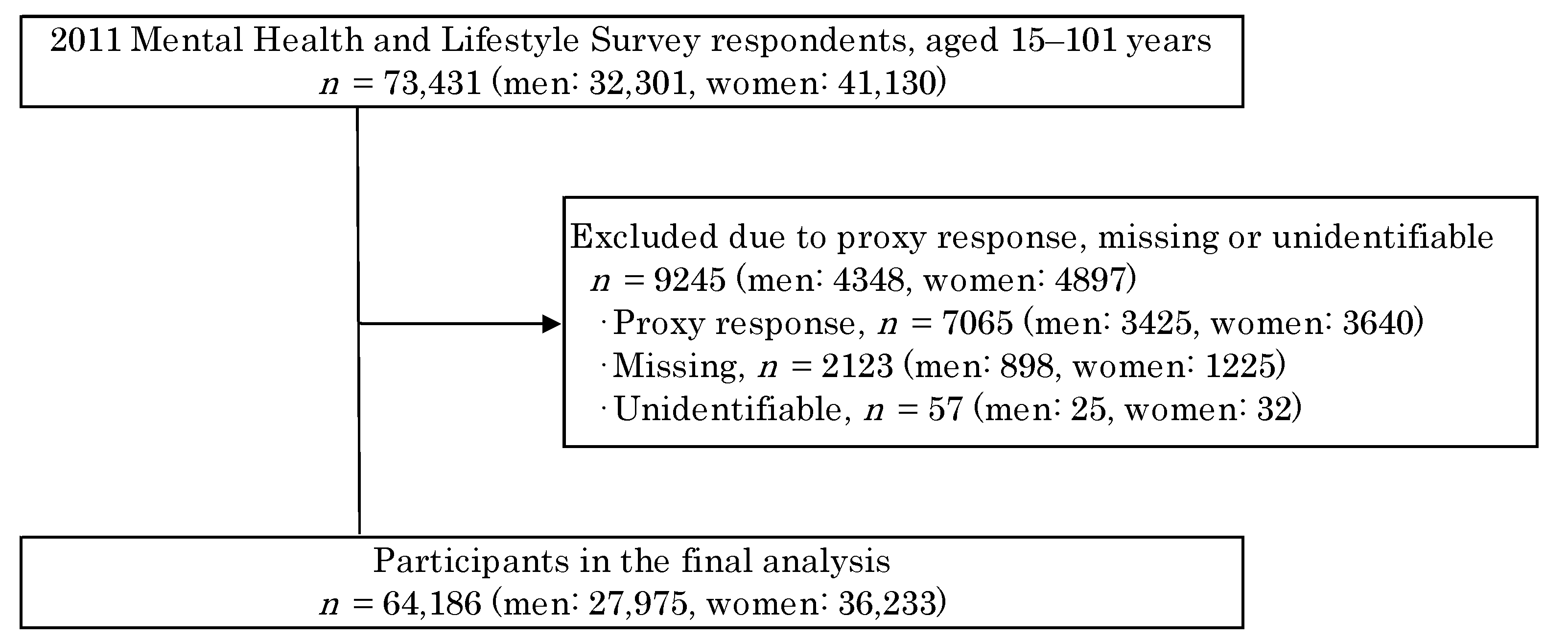

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Oral Symptoms

2.2.2. Psychological Factors

2.2.3. Experience of the Great East Japan Earthquake

2.2.4. Medical History and Current Health Condition

2.2.5. Lifestyle Factors and Other Confounding Factors

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants and Prevalence of Oral Symptoms

3.2. Multivariate Adjustment Analysis of Psychosocial Factors

3.2.1. Prevalent Oral Symptoms

3.2.2. Exacerbated Oral Symptoms

3.3. Multivariate Analysis for Prevalent and for Exacerbated Oral Symptoms on Psychosocial Factors by Sex and Age Category

3.3.1. Prevalent Oral Symptoms for Each of the Sexes

3.3.2. Exacerbated Oral Symptoms for Each of the Sexes

3.3.3. Prevalent Oral Symptoms for Each of the Age Category

3.3.4. Exacerbated Oral Symptoms for Each of the Age Category

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satoh, H.; Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Sakai, A.; Watanabe, T.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, A.; Kobashi, G.; et al. Evacuation after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident Is a Cause of Diabetes: Results from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 627390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohira, T.; Hosoya, M.; Yasumura, S.; Satoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai, A.; Ohtsuru, A.; Kawasaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Ozasa, K.; et al. Effect of Evacuation on Body Weight after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Mashiko, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Hisata, M.; Niwa, S.-I.; Yasumura, S.; Yamashita, S.; Kamiya, K.; Abe, M.; et al. Psychological Distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: Results of a Mental Health and Lifestyle Survey Through the Fukushima Health Management Survey in Fy2011 and Fy2012. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2014, 60, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, F.H.; Perilla, J.L.; Riad, J.K.; Kaniasty, K.; Lavizzo, E.A. Stability and Change in Stress, Resources, and Psychological Distress Following Natural Disaster: Findings from Hurricane Andrew. Anxiety Stress Coping 1999, 12, 363–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, C.S.; Ursano, R.J.; Wang, L. Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Depression in Disaster or Rescue Workers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Kawakami, N.; Kobayashi, S.; Ogawa, A.; Tannno, K.; Onoda, T.; Yaegashi, Y.; Sakata, K. Mental Health and Related Factors after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, M.; Fujii, S.; Maeda, M.; Nagai, M.; Harigane, M.; Miura, I.; Yabe, H.; Ohira, T.; Takahashi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Three-Year Trend Survey of Psychological Distress, Post-Traumatic Stress, and Problem Drinking among Residents in the Evacuation Zone after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident [The Fukushima Health Management Survey]. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 70, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Ohira, T.; Yasumura, S.; Maeda, M.; Otsuru, A.; Harigane, M.; Horikoshi, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Yabe, H.; Nagai, M.; et al. Effects of Socioeconomic Factors on Cardiovascular-Related Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study Using Data from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kishi, M.; Aizawa, F.; Matsui, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Abe, A.; Minami, K.; Suzuki, R.; Miura, H.; Sakata, K.; Ogawa, A. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Related Factors among Residents in a Disaster Area of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Giant Tsunami. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tubert-Jeannin, S.; Riordan, P.J.; Morel-Papernot, A.; Porcheray, S.; Saby-Collet, S. Validation of an Oral Health Quality of Life Index (GOHAI) in France . Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, H.; Amano, A. Roles of Oral Bacteria in Cardiovascular Diseases--from Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Cases: Implication of Periodontal Diseases in Development of Systemic Diseases. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 113, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraoka, K.; Kawahara, K. Survey of Dental Healthcare System Preparedness for Large-Scale Disaster. J. Stomatol. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 74, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amarasena, N.; Kapellas, K.; Brown, A.; Skilton, M.R.; Maple-Brown, L.J.; Bartold, M.P.; O’Dea, K.; Celermajer, D.; Slade, G.D.; Jamieson, L. Psychological Distress and Self-Rated Oral Health among a Convenience Sample of Indigenous Australians. J. Public Health Dent. 2015, 75, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.; Hamaguchi, T. Relationship between Periodontitis and Lifestyle and Health Status. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2001, 43, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Aida, J.; Watanabe, T.; Shinoda, M.; Sugawara, Y.; Tomata, Y.; Yabe, Y.; Sekiguchi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Osaka, K.; et al. High Prevalence of Toothache among Great East Japan Earthquake Survivors Living in Temporary Housing. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2019, 47, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasumura, S.; Hosoya, M.; Yamashita, S.; Kamiya, K.; Abe, M.; Akashi, M.; Kodama, K.; Ozasa, K. Study Protocol for the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Ohira, T.; Zhang, W.; Nakano, H.; Maeda, M.; Yasumura, S.; Abe, M. Fukushima Health Management Survey Lifestyle-Related Factors that Explain Disaster-Induced Changes in Socioeconomic Status and Poor Subjective Health: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T.A.; Kawakami, N.; Saitoh, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakane, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Tachimori, H.; Iwata, N.; Uda, H.; Nakane, H.; et al. The Performance of the Japanese Version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, E.B.; Jones-Alexander, J.; Buckley, T.C.; Forneris, C.A. Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yabe, H.; Horikoshi, N.; Yasumura, S.; Kawakami, N.; Ohtsuru, A.; Mashiko, H.; Maeda, M.; Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Diagnostic Accuracy of Japanese Posttraumatic Stress Measures after a Complex Disaster: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genco, R.J.; Ho, A.W.; Kopman, J.; Grossi, S.G.; Dunford, R.G.; Tedesco, L.A. Models to Evaluate the Role of Stress in Periodontal Disease. Ann. Periodontol. 1998, 3, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcenes, W.S.; Sheiham, A. The Relationship between Work Stress and Oral Health Status. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 35, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munck, A.; Guyre, P.M.; Holbrook, N.J. Physiological Functions of Glucocorticoids in Stress and Their Relation to Pharmacological Actions. Endocr. Rev. 1984, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbe, H.; Iwai-Liao, Y.; Senba, E. Stress-Induced Hyperalgesia: Animal Models and Putative Mechanisms. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.F.; Thompson, R.L.; Paunovich, E.D. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Considerations for Dentistry. Quintessence Int. 2004, 35, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, D.M.A.O.; Vaz, C.C.d.O.; Stuginski-Barbosa, J.; Conti, P.C.R. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Temporomandibular Dysfunction: A Review and Clinical Implications. BrJP 2018, 1, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C. A Cross-Sectional Study on the Current Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Adults Orphaned by Tangshan Earthquake in 1976. Chin. Mental Health J. 2008, 22, 469–473. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.-P.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, Z.-C.; Lei, Y.-X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.-X. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Survivors Five Years after the “Wenchuan” Earthquake in China. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanji, F.; Tomata, Y.; Sekiguchi, T.; Tsuji, I. Period of Residence in Prefabricated Temporary Housing and Psychological Distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Longitudinal Study. BMJ Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, N.; Nakamura, T.; Tsuchiya, N.; Narita, A.; Tsuji, I.; Hozawa, A.; Tomita, H. Prospect of Future Housing and Risk of Psychological Distress at 1 Year after an Earthquake Disaster. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 70, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawase, T. Social Sharing of Emotion, Social Support, and Psychological Well-Being among Unemployed Persons. Bull. Miyazaki Munic. Univ. Fac. Hum. 2003, 10, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S. Sociological Research on the Effects of Disaster on Jobs and the Consequential Change in Attitudes. J. Jpn. Soc. Nat. Disaster Sci. 2019, 38, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, K. Histological Studies on the Wistar Rats Fed Cholesterol, Sodium Cholate and Methylthiouracil, with Special Reference to the Changes of the Periodontal Tissues. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi 1965, 32, 368–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ohira, T.; Nakano, H.; Okazaki, K.; Hayashi, F.; Yumiya, Y.; Sakai, A.; for the Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. Trends in Lifestyle-Related Diseases before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 2018, 67, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta-Roy, A.K. Insulin Mediated Processes in Platelets, Erythrocytes and Monocytes/Macrophages: Effects of Essential Fatty Acid Metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 1994, 51, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentoglu, O.; Bozkurt, F.Y. The Bi-Directional Relationship between Periodontal Disease and Hyperlipidemia. Eur. J. Dent. 2008, 2, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardardóttir, I.; Grünfeld, C.; Feingold, K.R. Effects of Endotoxin and Cytokines on Lipid Metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 1994, 5, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, C.; Shin, W.S.; Minabe, M.; Harai, K.; Kato, K.; Seino, H.; Goke, E.; Sasaki, N.; Fujino, T.; Kuribayashi, N.; et al. Analysis of the Relationship between Periodontal Disease and Atherosclerosis within a Local Clinical System: A Cross-Sectional Observational Pilot Study. Odontology 2015, 103, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Flugelman, M.Y.; Goldberg, A.; Heft, M. Association between Periodontal Pockets and Elevated Cholesterol and Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels. J. Periodontol. 2002, 73, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loos, B.G.; Van Dyke, T.E. The Role of Inflammation and Genetics in Periodontal Disease. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchison, K.A.; Der-Martirosian, C.; Gift, H.C. Components of Self-Reported Oral Health and General Health in Racial and Ethnic Groups. J. Public Health Dent. 1998, 58, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buset, S.L.; Walter, C.; Friedmann, A.; Weiger, R.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Zitzmann, N.U. Are Periodontal Diseases Really Silent? A Systematic Review of Their Effect on Quality of Life. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsu, T.; Ueno, M.; Shinada, K.; Ohara, S.; Wright, F.A.C.; Kawaguchi, Y. Association of Clinical Oral Health Status with Self-Rated Oral Health and GOHAI in Japanese Adults. Community Dent. Health 2011, 28, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horikoshi, N.; Iwasa, H.; Yasumura, S.; Maeda, M. The Characteristics of Non-Respondents and Respondents of a Mental Health Survey among Evacuees in a Disaster: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2017, 63, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Sex | Age Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ≤49 Years | 50–69 Years | ≥70 Years | |

| n | 27,953 (43.55) | 36,233 (56.45) | 22,657 (35.3) | 26,139 (40.7) | 15,390 (24.0) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 56.4 ± 17.5 | 54.3 ± 17.9 | 34.8 ± 9.0 | 60.1 ± 5.4 | 76.9 ± 5.2 |

| 49 years old or younger (n, %) | 8969 (32.1) | 13,688 (37.8) | |||

| 50 to 69 years (n, %) | 11,916 (42.6) | 14,223 (39.3) | |||

| 70 years old or older (n, %) | 7068 (25.3) | 8322 (23.0) | |||

| Disaster-related factors | |||||

| PTSD symptoms (n, %) | 4848 (18.1) | 8217 (24.2) | 4001 (17.8) | 5379 (21.4) | 3685 (28.3) |

| Psychological distress (n, %) | 3132 (11.9) | 5585 (16.7) | 3124 (14.0) | 3656 (14.8) | 1937 (15.3) |

| Experience of evacuation (n, %) | 13,170 (47.1) | 16,835 (46.5) | 11,147 (49.2) | 12,239 (46.8) | 6619 (43.0) |

| Experience of tsunami (n, %) | 6718 (24.0) | 6314 (17.4) | 4160 (18.4) | 5164 (19.8) | 3708 (24.1) |

| Experience of nuclear accident (explosion heard) (n, %) | 15,465 (55.3) | 18,301 (50.5) | 10,458 (46.2) | 14,127 (54.1) | 9181 (59.7) |

| House damage (major) (%) | 4157 (15.8) | 5339 (15.9) | 2911 (14.0) | 4107 (16.7) | 2478 (17.3) |

| Job loss (n, %) | 5142 (18.4) | 8285 (22.9) | 5289 (23.3) | 6452 (24.7) | 1686 (11.0) |

| Work change (n, %) | 15,095 (56.7) | 18,270 (55.0) | 13,249 (59.5) | 14,491 (57.8) | 5625 (44.8) |

| Loss of a close person (n, %) | 5153 (19.0) | 7317 (20.8) | 3827 (17.1) | 5363 (20.9) | 3280 (22.9) |

| Medical history | |||||

| Mental illness (n, %) | 1137 (4.2) | 1942 (5.6) | 1144 (5.2) | 1225 (4.8) | 710 (5.0) |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 12,625 (45.8) | 13,385 (37.6) | 2464 (10.9) | 12,440 (48.4) | 11,106 (74.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 6327 (23.3) | 5755 (16.5) | 1047 (4.7) | 5675 (22.3) | 5360 (38.1) |

| Dyslipidemia (n, %) | 10,219 (37.6) | 12,106 (34.5) | 3241 (14.4) | 11,572 (45.3) | 7512 (52.8) |

| Current poor health condition (n, %) | 4798 (17.5) | 6817 (19.3) | 2836 (12.6) | 5109 (19.9) | 3670 (24.9) |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||

| Current smoking habit (n, %) | 9247 (33.5) | 3912 (11.3) | 6836 (30.3) | 5138 (20.2) | 1185 (8.3) |

| Current drinking habit (n, %) | 18,539 (66.9) | 10,437 (30.0) | 10,632 (47.1) | 13,088 (50.8) | 5256 (36.3) |

| Current exercise habit (once a week or less) (n, %) | 16,850 (61.7) | 23,620 (67.0) | 18,374 (81.5) | 16,410 (63.9) | 5686 (39.7) |

| Oral symptoms | |||||

| Absent (n, %) | 24,802 (88.7) | 31,769 (87.7) | 20,273 (89.5) | 22,713 (86.9) | 13,585 (88.3) |

| Prevalent (n, %) | 2775 (9.9) | 3827 (10.6) | 1985 (8.8) | 2986 (11.4) | 1631 (10.6) |

| Exacerbated (n, %) | 376 (1.4) | 637 (1.8) | 399 (1.8) | 440 (1.7) | 174 (1.1) |

| Variables | Model 1 1 ORs (95% CI) | Model 2 2 ORs (95% CI) 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalent | ||

| Disaster-related factors | ||

| PTSD symptoms (Ref. no) | 2.59 (2.45–2.74) | 1.80 (1.57–2.07) |

| Work change (Ref. no) | 1.47 (1.39–1.55) | 1.18 (1.04–1.35) |

| Experience of nuclear accident (explosion heard) (Ref. no) | 1.46 (1.38–1.53) | 1.18 (1.05–1.33) |

| Loss of a close person (Ref. no) | 1.44 (1.36–1.53) | 1.15 (1.01–1.32) |

| Experience of evacuation (Ref. no) | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | 1.06 (0.95–1.20) |

| Job loss (Ref. no) | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) |

| Experience of tsunami (Ref. no) | 1.33 (1.26–1.42) | 0.93 (0.79–1.08) |

| House damage (Ref. minor or none) | 1.27 (1.19–1.36) | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) |

| Medical history | ||

| Mental illness (Ref. no) | 2.43 (2.22–2.67) | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) |

| Dyslipidemia (Ref. no) | 1.41 (1.33–1.49) | 1.32 (1.15–1.50) |

| Diabetes mellitus (Ref. no) | 1.28 (1.20–1.37) | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) |

| Hypertension (Ref. no) | 1.25 (1.18–1.33) | 1.20 (1.05–1.38) |

| Current poor health condition (Ref. good) | 3.10 (2.93–3.28) | 2.12 (1.85–2.44) |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Current exercise habit (once a week or less) (Ref. twice a week or more) | 1.14 (1.08–1.21) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) |

| Current smoking habit (Ref. no) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 1.05 (0.92–1.21) |

| Women (Ref. men) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) |

| Age categories (Ref. ≥70 years) | ||

| ≤49 years | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) |

| 50–69 years | 1.24 (1.17–1.30) | 1.17 (0.98–1.40) |

| Exacerbated | Model 1 1 ORs (95% CI) | Model 2 2 ORs (95% CI) |

| Disaster-related factors | ||

| PTSD symptoms (Ref. no) | 4.07 (3.58–4.64) | 2.24 (1.64–3.06) |

| Work change (Ref. no) | 2.32 (2.01–2.69) | 1.88 (1.34–2.65) |

| Loss of a close person (Ref. no) | 1.92 (1.67–2.20) | 1.25 (0.92–1.71) |

| Job loss (Ref. no) | 1.84 (1.61–2.11) | 1.11 (0.81–1.51) |

| Experience of evacuation (Ref. no) | 1.84 (1.62–2.09) | 1.20 (0.91–1.58) |

| Experience of nuclear accident (explosion heard) (Ref. no) | 1.76 (1.55–2.01) | 1.11 (0.84–1.47) |

| House damage (Ref. minor or none) | 1.58 (1.35–1.85) | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) |

| Experience of tsunami (Ref. no) | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | 1.14 (0.81–1.60) |

| Medical history | ||

| Mental illness (Ref. no) | 2.33 (1.87–2.89) | 0.98 (0.60–1.62) |

| Dyslipidemia (Ref. no) | 1.66 (1.45–1.91) | 1.74 (1.27–2.39) |

| Hypertension (Ref. no) | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | 0.99 (0.70–1.42) |

| Diabetes mellitus (Ref. no) | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 0.76 (0.48–1.20) |

| Current poor health condition (Ref. good) | 4.27 (3.75–4.87) | 2.73 (2.00–3.75) |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Current smoking habit (Ref. no) | 1.28 (1.09–1.49) | 1.09 (0.80–1.48) |

| Current exercise habit (once a week or less) (Ref. twice a week or more) | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | 1.09 (0.79–1.52) |

| Women (Ref. men) | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | 1.10 (0.83–1.47) |

| Age categories (Ref. ≥70 years) | ||

| ≤49 years | 1.14 (1.01–1.30) | 3.83 (1.90–7.73) |

| 50–69 years | 1.16 (1.02–1.31) | 2.48 (1.26–4.88) |

| Variables | Sex | Age Category | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalent | Men 1 | Women 1 | ≤49 Years 2 | 50–69 Years 2 | ≥70 Years 2 |

| n | 21,957 | 26,060 | 19,014 | 20,420 | 8583 |

| Women (Ref. men) | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) | 1.01 (0.92–1.12) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | ||

| Age category (Ref. ≥70 years) | |||||

| ≤49 years | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.98 (0.84–1.13) | |||

| 50–69 years | 1.15 (1.02–1.31) | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | |||

| Disaster factors | |||||

| PTSD symptoms (Ref. no) | 1.81 (1.62–2.02) | 1.72 (1.57–1.90) | 1.74 (1.53–1.99) | 1.77 (1.59–1.96) | 1.82 (1.55–2.14) |

| Experience of evacuation (Ref. no) | 1.16 (1.05–1.28) | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | 1.02 (0.91–1.13) | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | 1.08 (0.92–1.26) |

| Experience of tsunami (Ref. no) | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) | 1.04 (0.94–1.17) | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | 1.28 (1.08–1.51) |

| Experience of nuclear accident (explosion heard) (Ref. no) | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 1.11 (1.01–1.21) | 1.08 (0.97–1.21) | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 1.24 (1.06–1.47) |

| House damage (Ref. minor or none) | 0.95 (0.83–1.07) | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 1.07 (0.95–1.21) | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) |

| Job loss (Ref. no) | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 1.07 (0.94–1.23) | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) |

| Work change (Ref. no) | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 1.18 (1.07–1.30) | 1.21 (1.07–1.37) | 1.16 (1.04–1.29) | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) |

| Loss of a close person (Ref. no) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 1.17 (1.06–1.29) | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) | 1.17 (0.99–1.38) |

| Medical history | |||||

| Mental illness (Ref. no) | 1.40 (1.17–1.69) | 1.37 (1.18–1.59) | 1.10 (0.90–1.34) | 1.59 (1.34–1.90) | 1.56 (1.19–2.04) |

| Dyslipidemia (Ref. no) | 1.26 (1.13–1.40) | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 1.22 (1.05–1.43) | 1.19 (1.08–1.31) | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) |

| Hypertension (Ref. no) | 1.01 (0.91–1.13) | 1.05 (0.94–1.17) | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.94 (0.79–1.11) |

| Diabetes mellitus (Ref. no) | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | 1.24 (0.98–1.58) | 1.04 (0.93–1.17) | 1.04 (0.87–1.23) |

| Current poor health condition (Ref. good) | 2.32 (2.08–2.59) | 2.19 (1.99–2.42) | 2.19 (1.91–2.52) | 2.15 (1.94–2.39) | 2.49 (2.13–2.91) |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||

| Current smoking habit (Ref. no) | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 0.79 (0.59–1.06) |

| Current exercise habit (once a week or less) (Ref. twice a week or more) | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | 1.04 (0.94–1.14) | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) |

| Exacerbated | Men 1 | Women 1 | ≤49 years 2 | 50–69 years 2 | ≥70 years 2 |

| n | 20,087 | 23,825 | 17,712 | 18,425 | 7775 |

| Women (Ref. men) | 1.16 (0.90–1.49) | 1.41 (1.10–1.80) | 0.89 (0.57–1.38) | ||

| Age category (Ref. ≥70 years) | |||||

| ≤49 years | 1.78 (1.18–2.67) | 2.04 (1.38–2.99) | |||

| 50–69 years | 1.22 (0.85–1.76) | 1.82 (1.29–2.89) | |||

| Disaster factors | |||||

| PTSD symptoms (Ref. no) | 3.10 (2.39–4.03) | 2.33 (1.88–2.89) | 2.99 (2.32–3.86) | 2.24 (1.75–2.87) | 2.79 (1.75–4.46) |

| Experience of evacuation (Ref. no) | 1.24 (0.97–1.60) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 0.94 (0.75–1.19) | 1.38 (1.08–1.76) | 2.08 (1.29–3.34) |

| Experience of tsunami (Ref. no) | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 1.00 (0.78–1.27) | 0.92 (0.69–1.22) | 0.91 (0.68–1.20) | 0.78 (0.47–1.31) |

| Experience of nuclear accident (explosion heard) (Ref. no) | 1.46 (1.12–1.91) | 1.06 (0.87–1.30) | 1.14 (0.90–1.44) | 1.21 (0.95–1.54) | 1.41 (0.84–2.36) |

| House damage (Ref. minor or none) | 1.05 (0.78–1.42) | 1.22 (0.96–1.56) | 1.10 (0.81–1.48) | 1.32 (1.00–1.73) | 0.84 (0.49–1.45) |

| Job loss (Ref. no) | 0.95 (0.71–1.25) | 1.15 (0.91–1.44) | 1.13 (0.87–1.46) | 0.91 (0.70–1.19) | 1.26 (0.70–2.25) |

| Work change (Ref. no) | 1.95 (1.43–2.64) | 1.52 (1.19–1.94) | 1.84 (1.36–2.48) | 1.79 (1.34–2.38) | 1.11 (0.68–1.84) |

| Loss of a close person (Ref. no) | 1.31 (0.998–1.72) | 1.50 (1.21–1.86) | 1.31 (1.00–1.70) | 1.53 (1.20–1.95) | 1.53 (0.96–2.44) |

| Medical history | |||||

| Mental illness (Ref. no) | 0.78 (0.49–1.26) | 1.14 (0.82–1.58) | 0.73 (0.48–1.11) | 1.31 (0.88–1.96) | 1.03 (0.46–2.33) |

| Dyslipidemia (Ref. no) | 1.59 (1.23–2.07) | 1.40 (1.11–1.78) | 1.68 (1.25–2.26) | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) | 1.61 (0.98–2.65) |

| Hypertension (Ref. no) | 0.98 (0.74–1.30) | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) | 1.46 (1.05–2.03) | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 1.16 (0.67–2.01) |

| Diabetes mellitus (Ref. no) | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) | 0.90 (0.66–1.23) | 0.82 (0.51–1.33) | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | 0.87 (0.53–1.43) |

| Current poor health condition (Ref. good) | 2.90 (2.22–3.77) | 2.40 (1.93–3.00) | 2.58 (1.98–3.36) | 2.65 (2.06–3.42) | 2.14 (1.36–3.38) |

| Lifestyle factors | |||||

| Current smoking habit (Ref. no) | 1.30 (1.02–1.67) | 1.01 (0.77–1.33) | 1.15 (0.91–1.47) | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) | 1.03 (0.46–2.29) |

| Current exercise habit (once a week or less) (Ref. twice a week or more) | 1.00 (0.77–1.31) | 1.17 (0.93–1.46) | 1.28 (0.93–1.77) | 0.92 (0.73–1.17) | 1.40 (0.91–2.15) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Funakubo, N.; Tsuboi, A.; Eguchi, E.; Hayashi, F.; Maeda, M.; Yabe, H.; Yasumura, S.; Kamiya, K.; Takashiba, S.; Ohira, T.; et al. Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116054

Funakubo N, Tsuboi A, Eguchi E, Hayashi F, Maeda M, Yabe H, Yasumura S, Kamiya K, Takashiba S, Ohira T, et al. Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(11):6054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116054

Chicago/Turabian StyleFunakubo, Narumi, Ayaka Tsuboi, Eri Eguchi, Fumikazu Hayashi, Masaharu Maeda, Hirooki Yabe, Seiji Yasumura, Kenji Kamiya, Shogo Takashiba, Tetsuya Ohira, and et al. 2021. "Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 11: 6054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116054

APA StyleFunakubo, N., Tsuboi, A., Eguchi, E., Hayashi, F., Maeda, M., Yabe, H., Yasumura, S., Kamiya, K., Takashiba, S., Ohira, T., & Mental Health Group of the Fukushima Health Management Survey. (2021). Association between Psychosocial Factors and Oral Symptoms among Residents in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A Cross-Sectional Study from the Fukushima Health Management Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116054