The Influence of Masculinity and the Moderating Role of Religion on the Workplace Well-Being of Factory Workers in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Incorporating Masculinity and Religion into Workplace Well-Being

2.1. Masculinities and Well-Being in the Workplace

The social practices that undermine men’s health are often the instruments men use in the structuring and acquisition of power. Men’s acquisition of power requires, for example, that men suppress their needs and refuse to admit to or acknowledge their pain. Additional health-related beliefs and behaviors that can be used in the demonstration of hegemonic masculinity include the denial of weakness or vulnerability, emotional and physical control, the appearance of being strong and robust, dismissal of any need for help, a ceaseless interest in sex, the display of aggressive behavior and physical dominance [5] (p. 1389, emphasis in original).

2.2. Religious Masculinity and Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Contexts and Research Questions

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis and Interpretation

4. Result

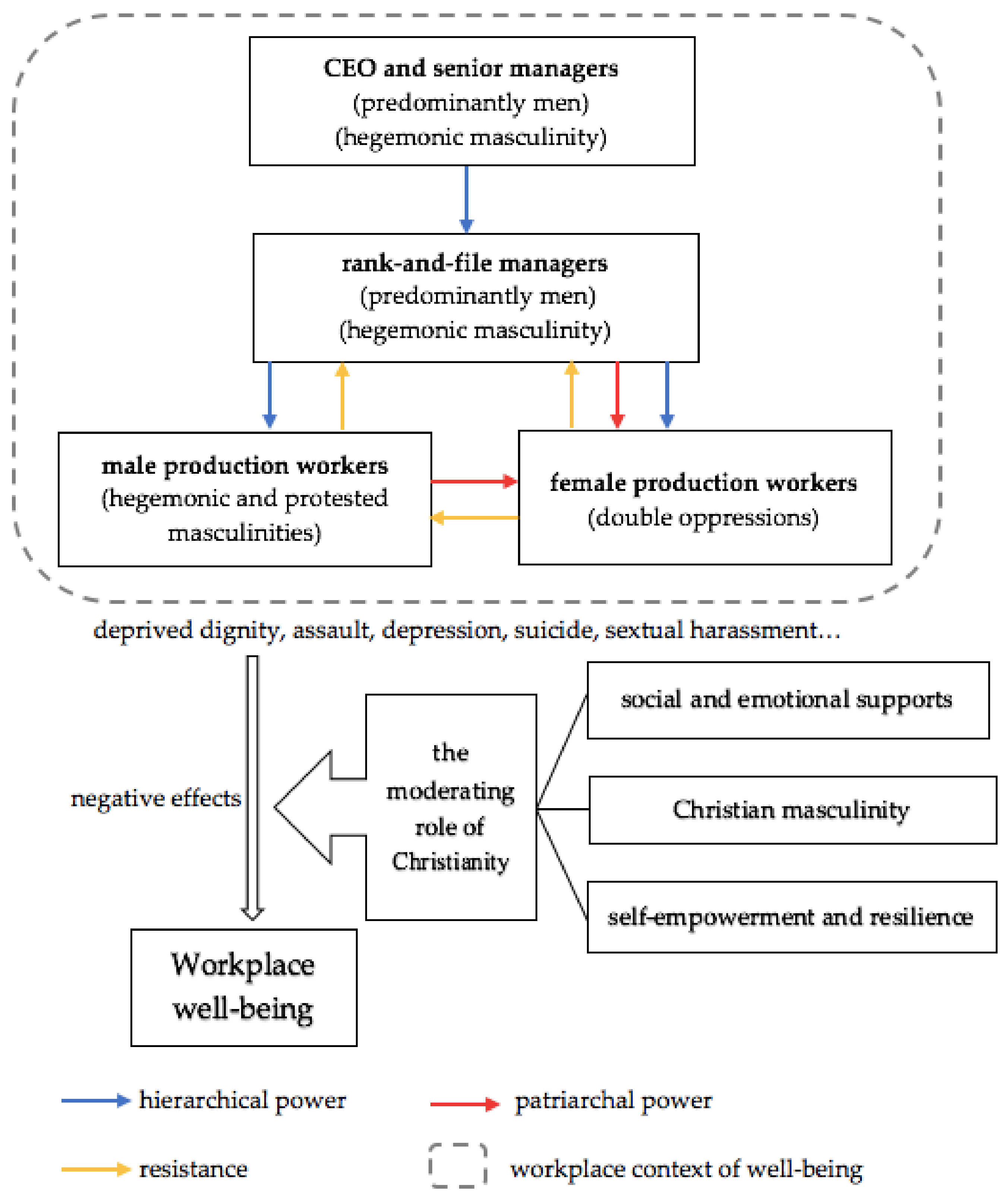

4.1. Contested and Hierarchical Masculinities and Their Influences on Well-Being within China’s Factories

The whole management system was designed by [the CEO]. He used to serve the military. You know, his personality, he is aggressive and dominating. He also required his subordinates acted like him. [He] doesn’t like others to ask him the rationale behind his orders and just needs you to be obedient, to follow and execute. If you can’t execute efficiently or make mistakes, he will scold you without any reservation. So, the atmosphere of Company A actually evolved from his own management philosophy.

The morning lecture is something like that: the line leader normally assembles all members to assign the tasks and tell us what needs to be cautious. However, it usually ends up with scolding workers by picking their mistakes. They just want to devalue you.

I felt really oppressed. When you want to go to the toilet, you even need to ask the line leaders’ permission! They normally replied you impatiently: “wait a moment, I need to find someone to temporally replace you”. Then, I needed to hang on an “off-position card” on my neck to go to the toilet. I felt I had no dignity.

In Company A, it was common that the security guards abused workers with dirty language if the workers forgot to bring or swab the factory ID card. The security guard group do not belong to any [factory] floor or department, they are directly managed by the senior managers in Company A. So security guards and production workers are two confrontational groups in Company A. I remember there was even a group flight between workers and security guards at the canteen a few years ago. The cause of the conflict was that one worker insulted the security guards by calling them “watchdogs”. So they came to blows and many workers participated in. You know, there were just 4–5 security guards at the canteen and they were fiercely beaten up by the workers.

Right after I was assigned to this assembly line, they asked me to assemble the phone screen, by just pressing the flexible printed circuit (FPC) into the phone model. I said: “OK, I have no objection”. But they asked me to do this every day, repeating the same action again and again with my two fingers. Other colleagues could switch to other operations but I wasn’t allowed to. So, I had pressed the FPCs for ten hours a day for one month and my fingers were injured already. After the first month, I talked to the line heads and asked them to let me shift to other positions, but they refused. The line head and assistant line head both asked me to continue. They (male lined leaders) said: “You do a good job on this. If I change to another one who is unfamiliar with this, he is more likely to destroy the FPCs, so more products will become scrap.”

4.2. The Moderating Effects of Christianity on Masculinity and Workplace Well-Being

In Company A, it is very easy to use abusive language to treat others. Gradually, we lost the ability to respect the colleagues and workmates around you. However, I don’t want to be that kind of supervisor, and I don’t want to be assimilated by this culture. This is against God’s teachings. When my subordinates made mistakes, I usually taught them what lessons can be learned rather than scolding them.

A girl (worker) said to me that she wanted to go to the toilet. We normally had a ten-minute break at 3:00 p.m. and now it was 2:45. So I politely responded, “It’s nearly 3 o’clock, you can take a break 15 min later”. The girl suddenly became extremely angry. It scared me, out of my expectation. I froze there, not knowing what I should say. Our line leader witnessed this scene… He said, “You shouldn’t let your workers deter you, you shouldn’t let her go to the toilet, it’s just 15 min”. I thought a while, said, “She is a girl, perhaps she was on her period and felt mood swings”. The line leader replied, “You shouldn’t act like that—consider the workers’ feelings. If you continue acting like this, being a laohaoren (one who tries to never offend anybody), you aren’t able to manage the workers”. I was thinking, if I acted coercively, it went against Bible’s teachings. The Bible teaches us to be benevolent and considerate of others.

In Company A, if a worker is often abused by his supervisors, he must have accumulated a lot of despair and hate. So, some workers chose to transferring their hate to others by abusing those who are weaker than them. For a Christian man, you should understand others’ sufferings. If a Christian is bullied by his supervisors, he should take the sufferings by himself rather than imposing your sufferings to others. It’s all God’s test on you.

Now, I don’t need to care about any rules and regulations any longer, because I am working for God, not for the boss. The purpose of work is to glorify God. If you have such spiritual state, you can be peaceful regardless of how they treat you.

Because you are a Christian, your behaviors must be more civil than them (non-Christian workers). Your inner life has changed, you have to live out the image of Jesus—manage your temper and control your emotional impulse. I used to often argue with the line leaders when I was unhappy. But after I converted to Christianity, I started to follow God’s teachings and I tried not to complain. It is my duty to do the work that I should do. Once you realised this, you can attain inner peace.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pun, N. Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pun, N.; Chan, J. The spatial politics of labor in China: Life, labor, and a new generation of migrant workers. South Atl. Q. 2013, 112, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J. Being Christians in urbanizing China: The epistemological tensions of the rural churches in the city. Curr. Anthropol. 2014, 55, S238–S247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. Reconstituting the neoliberal subjectivity of migrants: Christian theo-ethics and migrant workers in Shenzhen, China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, W.H. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, J.R.; Burns, S.M.; Syzdek, M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.C.; Rochlen, A.B. Introduction: Masculinity, identity, and the health and well-being of African American men. Psychol. Men Masc. 2013, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berdahl, J.L.; Cooper, M.; Glick, P.; Livingston, R.W.; Williams, J.C. Work as a masculinity contest. J. Soc. Issues 2018, 74, 422–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matos, K.; O’Neill, O.; Lei, X. Toxic leadership and the masculinity contest culture: How “win or die” cultures breed abusive leadership. J. Soc. Issues 2018, 74, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.; Koenig, H.G.; King, D.; Carson, V.B. Handbook of Religion and Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.; Elliott, M. Religion, health, and psychological well-being. J. Relig. Health 2010, 49, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Thoresen, C.E. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yim, J.Y.; Mahalingam, R. Culture, masculinity, and psychological well-being in Punjab, India. Sex Roles 2006, 55, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R.; Puigvert, L.; Rios, O. The new alternative masculinities and the overcoming of gender violence. International and Multidisciplinary. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 88–113. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, F.; Arciniega, G.M. Positive masculinity among Latino men and the direct and indirect effects on well-being. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 2015, 43, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.N.; Volkan, K.; Sechrist, K.R.; Pender, N.J. Health promoting life-styles of older adults: Comparisons with young and middle-aged adults, correlates and patterns. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1988, 11, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandrack, M.; Grant, K.R.; Segall, A. Gender differences in health related behaviour: Some unanswered questions. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, G.W. Disciplining protest masculinity. Men Masc. 2006, 9, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. Masculinities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q. The aspiration for moral manhood: Christianity, class and migrant workers’ negotiation of masculinities in Shenzhen, China. Geoforum 2019, 106, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, C.; Ridge, D.; Ziebland, S.; Hunt, K. Men’s accounts of depression: Reconstructing or resisting hegemonic masculinity? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2246–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, L.W. Male intolerance of depression: A review with implications for psychotherapy. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1983, 3, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczyk, J.; Figas, D.; Akulich, M.; Jazwinski, I. Mobbing in Banks: The Role of Gender and Position on the Process of Mobbing in Banks in Poland and Russia. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, 24, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.E. Toxic leadership. Mil. Rev. 2004, 84, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, P. Youthful Muslim masculinities: Gender and generational relations. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2006, 31, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökarıksel, B.; Sector, A. Devout Muslim masculinities: The moral geographies and everyday practices of being men in Turkey. Gend. Place Cult. 2017, 24, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerami, S. Islamist masculinity and Muslim masculinities. In Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities; Kimmel, M.S., Hearn, J., Connell, R.W., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 448–457. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, E. Masculinity in the new testament and early Christianity. Biblical Theol. Bull 2016, 46, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krondorfer, B. (Ed.) Men and Masculinities in Christianity and Judaism: A Critical Reader; Hymns Ancient and Modern Ltd.: Canterbury, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S.K.; Smith, C. Symbolic traditionalism and pragmatic egalitarianism: Contemporary evangelicals, families, and gender. Gender Soc. 1999, 13, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusco, E.E. The Reformation of Machismo: Evangelical Conversion and Gender in Colombia; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L.M. Spirituality, Suffering, and Illness—Ideas for Healing; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, M.M.; Allen, R.G. Spirituality as a means of coping with chronic illness. Am. J. Health Stud. 2004, 19, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G. Spirituality and mental health. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2010, 7, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Esquivel, G.B. Adolescent spirituality and resilience: Theory, research, and educational practices. Psychol. Schools 2011, 48, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.K. Navigating hardships in old age: Exploring the relationship between spirituality and resilience in later life. Qual. Health Res. 2013, 23, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lau, J.T.; Cheng, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhou, R.; Yu, C.; Holroyd, E.; Yeung, N.C. Suicides in a mega-size factory in China: Poor mental health among young migrant workers in China. Occup. Environ. Med. 2002, 69, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/SYrlzyhshbzb/dongtaixinwen/buneiyaowen/201705/t20170502_270286.html (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Pun, N.; Smith, C. Putting transnational labour process in its place: The dormitory labour regime in post-socialist China. Work Employ. Soc. 2007, 21, 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz, C.M.; Gu, D.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Huang, J.F.; He, J. Mortality from suicide and other external cause injuries in China: A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pew Research Center. Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Christian Population; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. Participant Observation; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Putnam, R.D. The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, O.; Kok, T.E. Moral or dirty leadership: A qualitative study on how juniors are managed in dutch consultancies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foucault, M. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault; University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, K. Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Sub-Category | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 40 |

| female | 20 | |

| Age | 16–30 | 35 |

| 30–40 | 15 | |

| 40–50 | 8 | |

| 50–60 | 2 | |

| Position | church leader | 8 |

| senior and middle manager * | 4 | |

| rank-and-file manager | 3 | |

| production worker | 49 |

| Examples of Illustrative Quote | 1st-Order Concepts | 2nd-Order Themes | Aggregate Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| militarized management | toxic leadership and hierarchical masculinity’s influence on well-being | masculinities’ influence on well-being |

| verbal abuse and bodily discipline | ||

| deprived dignity and depression | ||

| rebellious practices | protested masculinity’s influence on well-being | |

| domination over women | ||

| church as a space of equality | social and emotional supports | the moderating role of religion in masculinities’ influence on well-being |

| church as a space of relax | ||

| love and being considerate | Christian masculinity | |

| male headship | ||

| Christian interpretation of work | resilience and self-empowerment | |

| endurance and tolerance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Q.; Woods, O.; Cai, X. The Influence of Masculinity and the Moderating Role of Religion on the Workplace Well-Being of Factory Workers in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126250

Gao Q, Woods O, Cai X. The Influence of Masculinity and the Moderating Role of Religion on the Workplace Well-Being of Factory Workers in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126250

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Quan, Orlando Woods, and Xiaomei Cai. 2021. "The Influence of Masculinity and the Moderating Role of Religion on the Workplace Well-Being of Factory Workers in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126250

APA StyleGao, Q., Woods, O., & Cai, X. (2021). The Influence of Masculinity and the Moderating Role of Religion on the Workplace Well-Being of Factory Workers in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6250. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126250