Abstract

Background: This study investigated the impacts of the first COVID-19 UK lockdown on dog walking and ownership. Methods: An online survey was circulated via social media (May–June 2020). Completed responses (n = 584) were analysed using within- and between-group comparisons, and multivariable linear and logistic regression models were created. Open-ended data were coded into key themes. Results: During lockdown, dogs were walked less frequently, yet for a similar duration per week and closer to home. Dogs whose owners lived alone, or whose owners or household members had heightened vulnerability to COVID-19 were walked less than before, as were high-energy dogs. A minority of owners continued dog walking despite exhibiting symptoms or needing to self-isolate, justifying lack of help, dog behavioural problems, living in less populated areas, and the importance of outdoor exercise for their mental health. Dog ownership had multiple benefits (companionship, purpose and motivation; break from bad; positive to focus on) as well as challenges (changes in dog behaviour, balancing dog needs with public health guidance, accessing pet food/supplies and services, and sharing crowded outdoor spaces with others). Most did not have an emergency care plan for their pet before the pandemic and only a handful developed one. Conclusions: Findings can be used to inform public health and dog welfare strategies for future lockdown situations or other disasters and emergencies likely to impact on daily routines.

1. Introduction

Dog walking is an important public health practice that contributes to human health and dog welfare [1,2]. A recent UK study demonstrated that dog owners were four times more likely to meet the minimum physical activity guidance of 150 min per week than their non-dog-owning counterparts, substantially higher than found in other countries [3]. In addition to motivating owner exercise, dog walking has mental health benefits [4], particularly the longer ‘recreational walks’ undertaken after work and on weekends [5]. Exercise levels are also an important predictor of canine obesity [6], and amounts given vary widely within and between dog breeds [7]. A UK study estimated that on average, dogs are exercised 7 times per week, for a total of 220 min per week (approximately 30 min per walk) [3]. Once daily walking is considered a minimum requirement of a responsible dog owner [8], but frequency and duration of dog walks are affected by a number of factors, including dog size, access to suitable public spaces for dog walking, and the nature of the relationship between the dog and their owner(s) [9].

Strict ‘first lockdown’ measures (thereafter, ‘lockdown’) were imposed in the UK from 23 March 2020 until 10th May to control COVID-19 transmission between people. Specific rules between the UK nations varied, but lockdown restrictions allowed people to only leave their homes for medical help, to shop for essential items (e.g., food or medicines), perform essential work, and for once-a-day outdoor exercise [10,11]. Exercise was further restricted to local areas and for up to 1 h in some regions [10,11]. It was unclear whether these restrictions applied to dog walking [12], resulting in potential confusion and variability within and between regions. Dog walking was not explicitly addressed in English guidelines [13], and was interpreted in different ways by local authorities [11]. Scottish guidelines meanwhile stated that dogs could be taken out more than once a day [14], whereas guidelines for Northern Ireland required owners to include dog walking within their once-a-day exercise [15]. These rules and changes to people’s routines due to working from home or being furloughed [10] are likely to have altered the frequency, duration, and locations that owners walked their dogs and their experiences during dog walking.

Pandemic-related lockdowns are known to have impacted on pet owners and pets themselves in many countries. Data, including information obtained from the UK, suggests that dogs were identified as being a source of purpose, routine, sanity and entertainment for people during lockdown [16,17,18,19] and having a pet was protective against reduced mental health and increased loneliness [19]. An Australian study of people living alone also found that dog owners reported feeling less lonely during lockdown than people without a pet [20]. Having an excuse to leave the house and do exercise was an important aspect of owning a dog at this time, resulting in increased social interactions [17,20], with some giving their dogs more exercise than normal [16,20]. Likewise, in Canada, family dog ownership was positively associated with more active behaviour during COVID-19 restrictions, even as children had overall decreased physical activity, spent less time outside, and had increased sedentary behaviour and sleep [21].

Despite these overall benefits, owners expressed a number of concerns about dog walking during lockdown and around reduced quality of life for their pets. This included consequences related to closure of dog parks during lockdown and dogs not being allowed to exercise off-leash in some locations [22,23]. In the UK, dogs were more likely to have just one walk per day instead of 2–3, and whilst the total duration of daily walking exercise remained similar due to longer walks, dogs were less likely to be walked off-leash, were walked in less rural areas, and were less likely to be allowed to meet with other dogs [16,24]. Some owners considered that walks had become less enjoyable, because of perceived new dog owners in their area who did not respect social distancing or whose dogs were allegedly out of control [16,17]. UK pet owners also reported concerns about the impact of lack of socialisation, especially for puppies [17,24].

Others worried about contracting COVID-19 during dog walking. At the start of the pandemic, concerns about risk to human health posed by potential cross-species transmission of COVID-19 by dogs was thought to be low with human-to-dog transmission more likely than dog-to-human transmission [25]. A Spanish survey identified that 7% of respondents had concerns that dog walking increased the risk of COVID-19 infection [23], findings echoed by respondents to a UK-based survey [17]. Another Spanish study suggested that people who walked dogs were 78% more likely to report contracting COVID-19 [26], due to dogs being infected themselves or being a source of physical introduction of the virus into the house [26]. However, it is known from previous research that social interaction with other people is a common outcome of dog walking [4], and thus, increased reported chances of infection may have been due to physical proximity to other people (e.g., stopping and talking to each other), rather than virus transmission associated with the dogs themselves.

To date, studies focused on the impact of COVID-19 on dog ownership have explored various facets of human–dog interactions, including walking practices. However, these studies did not distinguish between walking undertaken by the dog, and a person’s activity walking with their dog, which may be different, particularly for multi-person households. The first aim of this study was to compare dog walking behaviour of UK owners and their dogs before and during the first lockdown (March/April 2020). We hypothesised that there may be differences in dog walking participation in single-person households compared to households with multiple members who could share the responsibility. Given the unprecedented changes in lifestyle triggered by the pandemic, the second aim was to invite dog owners to openly share the challenges and benefits of keeping and caring for a dog during these early stages of the pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Methodology

An online survey was conducted in the UK between 24 May and 11 June 2020. This study was approved by the University of Liverpool Veterinary Research Ethics Committee (VREC957) and was distributed via social media, including Facebook and Twitter. Many people acquired new pets during lockdown (e.g., “pandemic puppies” or rescue adoption [27]); however, our study recruited only those who had their dog both before and during this time, so that changes could be assessed. Dog owners also had to live in the UK and be over 18 years of age to be eligible to participate.

2.2. Survey Design

The questionnaire consisted of 64 open- and close-ended questions divided into 8 sections. Possible response options for questions not used in further analysis are listed below; the remaining options are provided in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material:

- •

- “About my dog”: number of dogs in the household; their size; age; sex; owner’s subjective assessment of their dog’s perceived energy levels (response categories were: low energy, medium energy and high energy; no further definitions or descriptions of behaviours that exemplify these categories were provided); and owner-perceived relationship with their dog (based on the Inclusion of the Other in the Self question adapted for pets [28,29]). Respondents were presented with seven images of circles with a progressing degree of an overlap between a circle representing a dog and an owner: starting with completely separate circles, representing a weak relationship, and ending with two nearly completely overlapping circles, representing a strong relationship). For questions relating to only one dog, respondents were asked to answer based on the dog they felt emotionally closest to. This strategy was chosen because dog walking is known to be associated with the strength of the relationship between the owner and the dog [9], and therefore this was the dog most likely to be walked pre-lockdown and thus affected by it.

- •

- “Walking this dog”: frequency of dog’s interactions with people and other dogs on walks before the lockdown; dog’s perceived recall reliability (response categories: dog never comes back when called, rarely, sometimes, often); weekly frequency and duration (in minutes) of dog walking undertaken by dog(s) during the lockdown and before (based upon the Dogs And Physical Activity tool [30]); perceived changes in total number of walks a dog gets from anyone since the lockdown; and perceived changes in how often a dog is off-lead, allowed to interact with other dogs and people since the social distancing measures were in place.

- •

- “Who walks dogs”: who walked the dog during lockdown and before; whether the person who walks the dog changed since the lockdown; and if so, how (open-ended question).

- •

- “Personal dog walking”: weekly frequency and duration (in minutes) of dog walking undertaken by the respondent during lockdown and before [30]; perceived changes in respondent’s number of dog walks since the lockdown and daily number of steps taken pre and during the first national lockdown (the type of a recording device was not specified, respondents may have used mobile phones or smart watches).

- •

- “Other dog walking”: location of dog walking both before and since the lockdown; perceived changes to walking location; description of these changes (open-ended question), whether COVID-19 changes brought the respondents into greater contact with livestock when walking; and attitude-related questions regarding experience of dog walking during the lockdown (e.g., Going for a dog walk offers a break from COVID anxiety). Responses to these questions were presented on a 5-point Likert scale anchored with “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree”.

- •

- “Perceptions of dog ownership”: whether caring for a dog during the period of social isolation has been challenging and helpful; two open-ended questions enquiring about ways in which caring for a dog was challenging and helpful during the lockdown; presence of an emergency care plan (defined in the survey as “verbal or written agreement about who would care for your dog if you were ill or other plans for an emergency”) and whether the respondent made one since the coronavirus outbreak.

- •

- “COVID questions”: whether the respondent experienced suspected COVID-19 disease and if so, whether they and household members walked their dog during the period when they had symptoms and when symptoms were not present any more but they were still within the designated isolation period; whether the respondent or household member was vulnerable and told to isolate for 12 weeks regardless of the symptoms and whether the vulnerable person continued to walk the dog whilst isolating.

- •

- “About you”: respondent’s age, gender, qualifications, and an open-ended questions about anything else regarding experience of dog walking during the coronavirus outbreak.

Some closed-ended questions included answer choice ‘Other- please specify’. These answers were re-coded by one of the co-authors (CW) where possible to match the pre-specified answers (e.g., in local woods was re-coded into pre-existing category “Woodlands”), or a new category was created (e.g., in response to the question about where dogs were walked during the lockdown, a category “private field” was created).

2.3. Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Data Handling

As part of checking the data for imputation errors, in line with previously published cut-off points, weekly walking duration was capped at 2520 min maximum (approximately 6 h a day) [31]. Values greater than this were considered as entered in error and were converted to 2520 ahead of the analysis. People living alone were identified by filtering those who answered “I live alone” to the question about other household members experiencing COVID-19 symptoms and the question about other household members being classed as vulnerable. Contradictory answers (e.g., answering “I live alone” to the first question and “Yes [other household members are vulnerable]” to the second one) were not used in the analysis. Relationship with a dog was recoded into 3 categories: strong (combined answers 6 and 7), medium (combined answers 5 and 4) and weak (combined 1, 2 and 3). All analysis was conducted in R (4.0.3) [32].

2.3.2. Multivariable Regression Analysis

To characterise our sample within the context of previous research on dog walking, multivariable generalised models with dog’s and person’s walking durations pre-lockdown used as an outcome variable were constructed. In both models, the outcome variable was log transformed. Dog-related variables (size, age, sex, energy levels, relationship with the owner), owner-related variables (age, gender, education, living arrangements: living alone or with others) and household-related variables (number of dogs in the household) were used as predictor variables [9]. Model fit is reported by describing F value, degrees of freedom, Cragg–Uhler Pseudo R2, and Akaike Information Criteria (AIC).

2.3.3. Within- and between-Group Comparisons

Data distributions were explored visually and with Shapiro–Wilks tests. As dog-walking durations were not normally distributed, the paired within-group changes (before-during lockdown) in weekly walking duration per dog (dog’s walking duration), owner (person’s walking duration) and in the number of steps taken as recorded by personal tracking devices were explored with the Mann–Whitney sum rank paired-samples test for comparison of distributions [33]. Changes in who walked the dog and locations where dogs were walked were explored with Cochran’s Q test extension of McNemar–Bowker tests. Comparison of where a dog was walked and presence/absence of an emergency care plan between those who did and did not live alone was carried out with a chi-square test. Analysis of differences in data distribution for dog’s and person’s walking was conducted for both the frequency and duration of dog walking, before and during the lockdown. For variables with multiple categories (i.e., living arrangements, number of dogs in the household, dog size, dog age, dog’s energy, relationship with a dog) data were analysed with Mann–Whitney test for unpaired data (where there were 2 categories) or Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) test (where there were more than 2 categories). Where the K-W test was significant, post-hoc follow-up Dunn tests with Benjamini–Hochberg (B-H) correction for multiple comparisons were used [34].

2.3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis

Two multivariable logistic regression models were created to explore (1) dog’s and (2) person’s walking changes during the lockdown (reduced total walking duration per week, compared to combined category “stayed the same or increased”). A full model was created using owners’ and household COVID-19 symptoms, owner and household self-declared heightened vulnerability to the virus, having an emergency care plan for the dog and owner- and dog-related demographic variables as predictor variables. Backward elimination method was used to identify significant variables (p < 0.05).

2.4. Qualitative Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was carried out. Answers to open-ended questions were coded line-by-line by the co-authors (CW and TMG), by assigning codes that captured the main sentiments conveyed within and across responses [35]. Initial codes were revised throughout the coding process to ensure codes accurately reflected the text. Codes were then compared and grouped and patterns emerging from the initial coding were discussed between the co-authors. After further revision the main themes were discussed and identified [35].

3. Results

3.1. Owner and Dog Characteristics

A total of 995 respondents began/half-completed the survey. Of these, 941 were eligible, and 584 completed the survey to the end and were included in the analysis.

Most respondents had 1 dog (56.0%, n = 327), followed by 2 dogs (29.8%, n = 174) and 3 or more (14.2%, n = 83). Most dogs were 1–5 years of age (50.7%, n = 296), 35.8% (n = 209) were aged 6–10, 8.6% (n = 50) were age 11+ and 5.0% (n = 29) were under 1 year of age. Slightly over half of dogs were male (53.4%, n = 312). Most dogs were described as medium size (41.7%, n = 242), 35.0% (n = 203) as large/giant and 23.3% (n = 135) as small/toy sized. Over half of dogs were considered medium energy (55.5%, n = 324), 7.2% (n = 42) as low and 37.3% (n = 218) as high energy.

Owners were mostly 30–50 years of age (43.2%, n = 252), followed by over 50 (37.9%, n = 221) and 18–29 (18.4%, n = 107). The majority identified as female (88.7%, n = 516), 10.5% (n = 61) identified as male and gender was not disclosed for 0.9% (n = 5). Most held a university level degree (69.0%, n = 400). Six respondents provided contradictory answers to the question to which “I live alone” was one of the answers. These responses were removed and 15.5% (n = 89) respondents were identified as living alone. Most respondents (91.4%, n = 533) had not developed COVID-19 symptoms at the time of questionnaire completion. However, 16.3% (n = 95) reported that someone else in their household had experienced symptoms. A small proportion of respondents (12.4%, n = 72) were classified as or considered themselves as vulnerable and were expected to isolate for 12 weeks.

Prior to the lockdown, most respondents (62.3%, n = 363) did not have an emergency care plan for their dog. Of those who did not have a care plan, 7.7% (n = 28) prepared one during the pandemic. Before the lockdown, a significantly higher proportion of those living alone (57.3%, n = 51) had a care plan compared to those living with other household members (33.5%, n = 163, p < 0.001).

3.2. Dog’s Walking before Lockdown

A multivariable regression model showed that longer walk duration before lockdown was associated with the following dog-related characteristics: large/giant dog size (compared to small/toy size) (p = 0.01) and high energy levels (compared to perceived low energy levels) (p < 0.001). In the same model, owner-related characteristics associated with longer walk duration included owners aged 30–50 years old (p = 0.001) and over 50 years of age (p = 0.03) compared to 18–30 years (Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Owners education to a A-level or equivalent level was negatively associated with dog walking duration compared to those educated to degree level (p = 0.01, Table S1 in Supplementary Material).

3.3. Differences in Dog’s Walking before and during Lockdown

Most respondents stated that there had been no difference in the weekly frequency of dog’s walks (from anyone) during lockdown (52.8%, n = 306), 27.8% (n = 161) reported a decrease and 19.5% (n = 113) reported an increase. Overall, dogs experienced a significant decrease in the frequency of walks during lockdown, with a weekly median frequency of walks for dogs reduced from 10 to 7 (p < 0.001 Table 1). Weekly frequency of dog’s walks during lockdown compared to before was significantly reduced for: dogs of owners living alone (p = 0.04) and those living with others (p = 0.009); single-dog (p = 0.03) and two-dog households (p = 0.04); dogs of medium (p = 0.04) and large/giant-size (p = 0.013); dogs aged 6–10 years old (p = 0.012); dogs perceived to be of high (p = 0.023) and medium energy (p = 0.04); and where owners rated the relationship strength as medium (p = 0.04) or strong (p = 0.02; Table 1). In contrast to before lockdown, there was evidence that dogs were walked more frequently during lockdown when from single- compared to two-dog households (p = 0.029), but no other significant differences were observed (Table 2). Total duration of walks before lockdown was significantly less in dogs perceived to have low compared to medium (p < 0.001) or high (p < 0.001) energy levels (Table 2).

Table 1.

Weekly frequency of dog’s and person’s walking before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Within-group comparison (change in the distribution of walking frequency between before and during the lockdown) is summarised with sample size (n), Mann–Whitney paired test-statistic (V) and significance levels (p).

Table 2.

Between-group differences in frequency of dog’s and person’s walks per week both before and during the lockdown are summarised with Mann-Whitney test-statistics where 2 categories were compared (V), K-W test-statistic (X2) where 3 or more categories were compared and test significance levels (p). Where the between-group comparison was statistically significant (p < 0.05), Dunn p values with further Benjamini–Hochberg FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons are provided.

Comparison of dog’s walking duration before and during the pandemic lockdown revealed no overall change (p = 0.41; median of 420 min, Supplementary Material, Table S1). Similar to the pattern observed for frequency of walks, before lockdown, dogs rated as low energy were walked for a significantly shorter weekly duration than those rated as high (p < 0.001) or medium (p = 0.04) energy (Table 3). A logistic regression model (Table 4), demonstrated that a reduction in dog’s total weekly walking duration during the lockdown was associated with dog owners who were vulnerable or were living with a vulnerable household member compared to not (p = 0.04) and nearly significant with owners who lived alone compared to with others (p = 0.06). The results of the multivariable logistic regression before backward elimination are summarised in the Supplementary Material, Table S3.

Table 3.

Between group differences for duration of walks both before and during the lockdown are summarised with Mann–Whitney test-statistic where 2 categories were compared (V), K-W test-statistic (X2) where 3 or more categories were compared and test significance levels (p). Where the between-group comparison was statistically significant (p < 0.05), Dunn p values with further Benjamini–Hochberg FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons are provided.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model for dog’s reduction in total weekly dog walking duration during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Model based on 514 observations, X2 = 6.72, p = 0.03, AIC = 642.98.

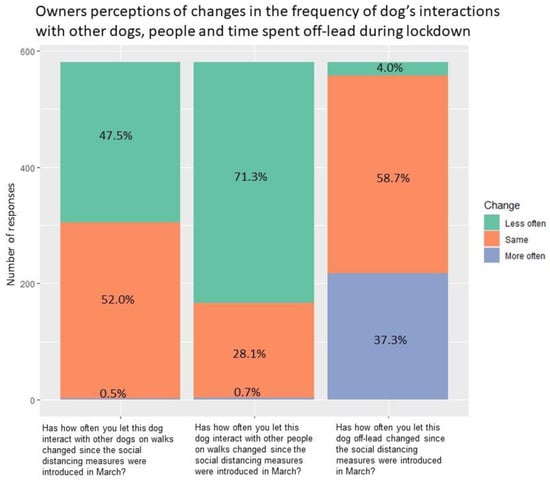

Only 9.4% (n = 55) of dogs had been brought into closer contact with livestock compared to before the lockdown. Further changes in social interactions on walks and how dogs were managed are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Owner’s perceptions of changes in the frequency of dog’s interactions with other dogs, people and time spent off-lead during lockdown.

3.4. Person’s Dog Walking before Lockdown

Prior to lockdown, between group comparison suggested that a person’s dog walking per week was significantly more frequent where they rated the relationship with the dog as strong (p = 0.012) or medium (p = 0.029) compared to weak, and strong compared to medium (p = 0.021, Table 2). Greater weekly dog walking duration was significantly associated with living alone (p < 0.001), dogs with high/medium energy levels compared to low (p < 0.001), and rating the relationship with a dog as strong or medium compared to weak (p < 0.05, Table 3). Multivariable regression modelling identified that an increased total weekly dog walking duration of a person was associated with having 3 or more dogs in the household (p = 0.03), dog’s high energy levels (p = 0.02), owners’ age 30–50 (p < 0.02), and owners living alone (p = 0.01). A reduced walking duration was associated with owners being educated at an A-level or equivalent level (p < 0.001, Table S4 in the Supplementary Material).

3.5. Differences in Person’s Dog Walking before and during Lockdown

When asked directly about perceived change in person’s dog walking, 48.8% of respondents (n = 273) reported no change, 27.0% (n = 151) reported a decrease and 23.6% (n = 132) reported an increase in the total number of weekly walks. During lockdown, within-group comparison demonstrated that reduced frequency was again significantly associated with a weaker relationship with the dog (Table 1). Frequency of person’s dog walking was significantly reduced during lockdown for people living alone (p = 0.02) and with others (p = 0.03), for two-dog households (p = 0.009), large/giant dogs (p = 0.04), dogs aged 6–10 years (p = 0.006), dogs rated to have high energy levels (p = 0.05) and where owners rated the relationship with dogs as strong (p = 0.01) (Table 1).

No significant differences in person’s walking duration were observed overall and the total median weekly durations during the lockdown compared to before were similar (Table 3 and Supplementary Material Table S2). Similar to pre-lockdown, person’s walking duration during the lockdown was significantly longer when living alone compared to living with others (p < 0.001) and where dog energy levels were rated as high or medium compared to low (p < 0.001) (Table 3). A logistic regression model (Table 5), demonstrated that a reduction in person’s total weekly walking duration during the lockdown was associated with owners who lived alone compared to with others (p = 0.02). The results of multivariable logistic regression analysis before backward elimination are summarised in the Supplementary Material, Table S5.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression model for reduction in person’s total weekly dog walking duration during the COVID-19 lockdown. Model based on 489 observations, X2 = 7.67, p = 0.02, AIC = 572.63.

Among the owners who provided a daily step count based on personal activity trackers (n = 106, 18.2% of all respondents), the mean number of steps taken daily before the lockdown (with and without dogs) was 9996 (SD = 3483.28) before and 9147.2 (SD = 3640.24) during lockdown. The median change of averaged daily step count was 568.6 fewer steps during the lockdown, but this change was not significant (p = 0.14).

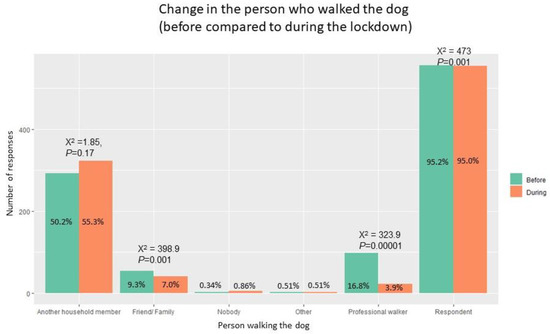

Nearly one-third of respondents (28.8%, n = 168) stated that a different person was walking their dog compared to pre-lockdown. Compared to before, during lockdown, significantly fewer people used dog walkers (p < 0.001) or other friends/family (p < 0.001) and more walked the dog themselves (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Qualitative analysis of open-text responses indicated that owners stopped using professional dog walking/care services or informal friends and family, because they were not allowed or because they did not need it any more as somebody else was able to walk the dog (working/studying from home, or being on furlough). However, others had no choice but to rely on friends and family for help due to a loss of professional dog walkers. Lockdown sometimes led to household members spending more time walking dogs together than previously, but more commonly they shared duties. Some household members and other carers who would normally dog walk were not able to due to COVID-19 symptoms or shielding.

Figure 2.

Person who walked the dog before and during the pandemic lockdown (McNemar’s X2 and p-value are provided where the sample size permitted a meaningful comparison).

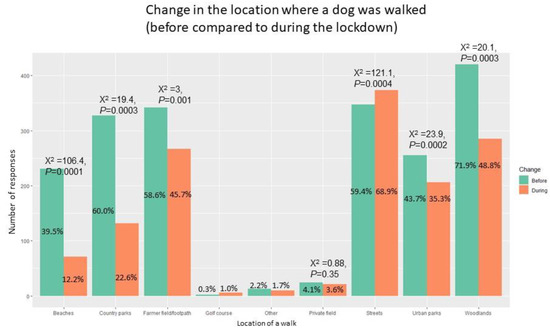

3.6. Change in Walking Location

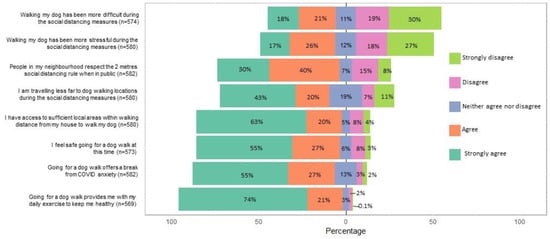

During lockdown, walking on streets (p < 0.001) increased, but decreased for urban parks (p < 0.001), beaches (p < 0.001), woodlands (p < 0.001), and country parks (p < 0.001) (Figure 3). Qualitative analysis of open-text responses indicated that as driving had been limited to essential travel only during lockdown, and concerns that some places and their car parks had closed, dog walking “stayed local,” with many happening directly “from the front door only”, “round the block/streets [and] then home”, often “rediscovering local footpaths”. Summary of questions on experience of dog walking during the pandemic lockdown, including questions regarding travel for walking is summarised in Figure 4. Most respondents stated that they were travelling shorter distances to dog walking locations 62.8% (n = 364) and agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they had access to sufficient local areas within walking distance from their house to walk their dog (83.6%, n = 483). Significantly more of those living alone changed their walking location compared to those who did not live alone (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Walking location before and during the pandemic lockdown (McNemar’s X2 and p-value are provided where the sample size permitted a meaningful comparison).

Figure 4.

Summary of questions regarding experiences of and attitudes towards dog walking during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

3.7. Dog Walking and Attitudes to COVID-19

Of those who experienced COVID-19 symptoms (n = 95), 38% (n = 19) continued to walk their dog when experiencing symptoms and 34% (n = 17) walked the dog when symptoms had passed but when they were still within the designated isolation period. A minority (3.2%, n = 3) of respondents reported that other household members were walking the dog when showing COVID-19 symptoms and 6.3% (n = 6) within the designated isolation period. Qualitative analysis highlighted that reasons for continuing to walk included not having anyone else to help; not trusting anyone else to help because dog is reactive (i.e., responds by pulling, lunging, barking, or growling to other dogs/people); living in rural areas or having access to own private land where they never see other people; presented symptoms early on in February, when little was known about the virus; and believing it was important for mental health, so long as extra precautions were taken (e.g., walking early in the morning or late at night to avoid others).

3.8. Benefits of Caring for a Dog during Lockdown

The majority of respondents reported that owning/caring for a dog during lockdown had been beneficial 91.2% (n = 529). Further summary of attitudes and experiences of walking during the lockdown and its impact on mental health are provided in Figure 4. The key themes identified in the course of qualitative analysis as benefits of caring for a dog during lockdown were: Companionship; Purpose and motivation; A break from the bad; A positive focus (Table 6).

Table 6.

Qualitative analysis of respondents answers regarding the benefits of owning and caring for a dog during the COVID-19 lockdown.

3.9. Challenges of Caring for a Dog during Lockdown

Owning and caring for a dog during the period of isolation/distancing had been challenging for a small proportion of respondents 16.3% (n = 95). Further summary of attitudes and challenging experiences related to dog walking during the pandemic lockdown is shown in Figure 4. The qualitative analysis elucidates the key themes identified as challenges for dog ownership and walking during lockdown as: concerns about actual or anticipated dog behavioural impacts; balancing public health guidelines with meeting dog’s welfare needs; conflicts in using crowded outdoor spaces with other users and coping strategies; risk of contracting COVID-19; accessing pet food, supplies and pet services (Table 7).

Table 7.

Challenges of owning and caring for a dog during the period of isolation/distancing.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to explore changes in dog walking of both owners and their dogs in the UK during the first lockdown (March/April 2020) of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government restrictions implemented to manage the transmission of COVID-19 and to prevent economic difficulties, including working from home and furlough schemes [10], are likely to have altered the frequency and locations that owners walked their dogs and their experiences during dog walking. Overall, results suggest good general compliance with emergency government regulations including being restricted to once daily outdoor exercise and reduced contact with other people. Dogs may have been walked less often per week, yet total weekly duration of walks stayed the same, meaning dog owners stayed out longer when they did walk. Compared to pre-lockdown, people walked their dog(s) closer to home. A potential public health risk was posed by a minority of owners or household members continuing to undertake dog walking whilst exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms or self-isolating following development of symptoms.

Responsibility for dog walking was often shared between household members—or before the pandemic, outsourced to a professional dog walker—to ensure that the dog’s needs are met. Professional dog walkers were significantly less likely to be called upon during lockdown, likely due to confusion regarding regulations, fear of contracting COVID-19, or people having more time to engage in dog walking themselves, potentially leading to health benefits for the owner but financial challenges for the professional dog walker. Nonetheless, both dogs and owners were more likely to have reduced dog walking duration during the first UK lockdown compared to their normal pre-lockdown routine if owners lived alone and/or considered themselves or someone in their household vulnerable to COVID-19. This may have been related to concerns by dog owners about risk of contracting COVID-19 during dog walking, similar to findings of other UK-based studies [17]. These findings were also consistent with previous UK research about the practical difficulties of dog walking for those who live alone [18], due to not having other household members who could walk the dog. Our findings suggest that restricting dog walking to once daily can have negative welfare impacts in particular for dogs with higher energy levels, or from multiple-dog households, as these dogs were walked significantly less during the lockdown compared to previously. In Montreal, Canada, the City imposed an 8pm curfew, allowing dog walking as the one exception outside of essential travel or emergencies, so long as walks remained within 1 km of home [36].

Respondents to the present study also adapted how and where they walked in accordance with government restrictions. Dogs spent more time on a leash and less time interacting with other dogs and people. Respondents travelled less to walk and dog walks occurred more often on streets, representing a shift from more recreational to functional walking locations [5]. Whilst this is likely to confer environmental benefits due to reduced pollution caused by driving [37], overcrowding in parks and green spaces was cited by some as a source of conflict between dog owners and other users, e.g., cyclists, people with children. To overcome this, some dogs were walked early in the morning or late at night, similar to findings from other UK-based research [17,24]. Future policy and programming should consider situations where dog walkers and other recreationists are expected to share common and different spaces, with focus on managing conflict and potential overcrowding. Most respondents believed that they had access to sufficient dog-supportive areas within walking distance from their house; however, opening areas normally not open to the public for dog walking (e.g., golf courses or school yards) during periods of high local demand for green spaces as well as educating park users about appropriate etiquette is advised.

In the present study, having a dog was considered by respondents to be a positive factor during the initial UK lockdown, providing companionship, purpose and motivation, a break from the bad, and a positive to focus on, all of which appears to be consistent with findings from other studies [17,19,38]. Respondents also reported on the value of physical contact with their dogs at a time where physical contact with others outside their household was prohibited, consistent with findings from another UK study where 90% of participants identified touch as a key way through which pets contributed to owner well-being [39]. Dog walking may also have been a key source of socially-distanced interaction with other people for those dog owners who lived alone. A small proportion of our respondents raised concerns regarding the potential risks of walking dogs. However, given research showing how beneficial dog walking is to individual physical health and low risk of contracting COVID-19 when outdoors, we believe that the benefits of walking the dog still outweigh the possible risk during this period of time.

Only 16.2% of respondents considered that owning and caring for a dog during lockdown had been challenging. This was a higher proportion than a recent UK study, where only 5% of respondents agreed with the statement “It would be easier for me not to have an animal at this time” [19]. Challenges that respondents stated included noticing behavioural changes in their dog or anticipating them, trying to follow public health guidelines while also meeting their pet’s needs, coping with crowding in parks, worrying about contracting COVID-19, and problems with accessing pet food and supplies, and related services (such as veterinary care, grooming, and dog day care). Similar challenges have been reported in other studies [40].

A separate set of challenges relates to providing care for a dog in case the owner is hospitalised. US-based research found that strength of pet attachment increased the odds of delaying treatment/testing for COVID-19; worrying about securing pet accommodation and organising care for their pet, were among the main reasons for delaying seeking help [40]. Similarly, when faced with floods, bushfires, or hurricane warnings, pet owners often delay evacuation and risk injury or even death by returning to their homes to rescue pets [41]. An emergency care plan for pets is therefore advisable, to improve the welfare of pets during pandemics and related emergencies and disasters and reduce health-risk to people such as delays in seeking help.

Indeed, although a higher proportion of respondents living alone had an emergency care plan for their dogs, less than half of respondents had a care plan before the pandemic and just 7.7% developed one during the lockdown. Our findings suggest that further work is needed to both help owners prepare for inevitable future emergencies [42] and to provide support to owners at those times. Dog walkers could play an important part during emergencies by supporting the vulnerable, those living alone, and those with high-energy, active dogs, in supplementing dog walking. Local governments and not-for-profit organisations could further enable this support by providing dog walking discounts to those most likely to need additional help, or by setting up informal dog-walking networks. In addition, dog owners should be offered guidelines on how to prepare an emergency care plan for their dogs. Local governments and not-for-profit organisations could offer a website where such care plans can be stored and updated, in case the owner was not able to communicate this.

Our respondents reported on dog behavioural impacts that had occurred as a result of the lockdown restrictions (for example, increased reactivity whilst walking), or concerns in anticipation about them in future (for example when returning to work). A study of Spanish pet (dog and cat) owners also reported worsening of dog behaviour problems within only a few weeks of restrictions [23], a finding that was supported by UK data identifying small increases in growling/snapping/nipping, barking and whining, jumping up, and being clingy and following people around the house during lockdown restrictions [24]. In addition, studies have identified a spike in paediatric dog bites corresponding to introduction of lockdown measures [43,44]. Given that both adults and children would be spending more time with dogs at home during the lockdown restrictions [24] and that dog owners had noticed worrying behaviour changes in dogs, promoting educational advice to prevent dog bites is important, for example providing dogs a safe space within the house where they can be undisturbed. Findings from the present study suggest that whilst additional indoor activities with dogs helped with dog management, they were not a replacement for dog’s usual outdoor exercise. Nonetheless, in similar future situations where walking and outdoor exercise are restricted for dogs, owners could be advised on environmental enrichment that could be performed within the home (e.g., puzzle-feeders, scent and training games). Whilst there is evidence that some forms of indoor enrichment such as human–dog interactive games with a dog and training increased during lockdown compared to pre-lockdown levels, other forms such as provision of toys had not [24] and could be further promoted through dog welfare charities and national media.

The characteristics of dog’s and person’s dog walking prior to the pandemic were consistent with previous studies of factors associated with dog walking [9], lending validity to our data. Measuring the levels of physical activity through personal tracking devices is a more objective approach than reliance on respondents self-reports, and helped to validate self-reported changes in dog walking. The sub-population of owners who provided objective measures of steps taken (with and without their dogs) averaged 9996 steps per day. Further, owners reported on average 350 min of dog walking per week, which is likely to mean that most of the study respondents substantially exceeded the UK’s physical activity recommendations of 150 min of at least moderate physical activity per week [45]. This is in line with previous research findings that dog owners are more likely than non-owners to meet the physical activity guidelines [3].

Limitations of this study include the potential for a biased population of respondents compared to the wider UK dog-owning population: the majority of respondents were female, a high proportion were university-level educated, relatively few were classed as ‘vulnerable’ to COVID-19 and most had not developed any COVID-19 symptoms at the time of completing the questionnaire. In addition, as respondents participating in this study are likely to be selectively biased to those more committed to their animals, it is likely they walk more than some dog owners. The confidence intervals of the logistic regression models are broad, likely due to this study being underpowered, but results were consistent with those from other studies with larger sample sizes. Most data explored here were largely self-reported, which may introduce further uncertainty in our analysis. Future similar studies should investigate in more detail the impact of dog owners spending more time at home, being furloughed, or living in urban or rural areas.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the variability in changes in dog walking during the first national COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. We found that, overall, both dogs and people reduced the frequency of walks. However, the overall weekly duration of walks for dogs did not drastically change, likely because owners walked for longer and because in multi-person households, dogs had more people to support them. Some owners, in particular those living alone, self-identified as vulnerable, or owning high-energy dogs, had reduced dog walking options, which may have implications for both dog welfare and owner well-being. Having a dog provided benefits during lockdown; however, there were significant challenges to meeting the needs of pets and accessing care or supplies. Future provisions should be made to prevent and manage conflict between dog owners and other recreationists in parks and green spaces. Further, emergency preparedness, including care plans for pets, should be promoted, as future events or conditions that require others to take care of individual’s pets are likely. In order to optimise dog and owner welfare in similar lockdown situations, future policy should at least consider allowing dog owners who live alone and those with high-energy dogs to exercise their dogs more than once a day and allowing professional dog walkers to continue to work. Our findings support the English 3rd national lockdown decision to designate dog walking as unlimited, under exemptions for animal welfare and exercise [46]. However, whether this is widely realised by the public is not currently known.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18126315/s1. Table S1: Multivariable regression analysis of variables associated with duration of dog’s walking before the first UK COVID-19 lockdown (March/April 2020). Model based on 510 observations. F(22) = 5.38, p = 0.00, Cragg-Uhler Pseudo-R2 = 0.28, AIC = 243.18.; Table S2: Weekly duration of dog’s and person’s walking before and during the COVID-19 first national lockdown. Within group comparison (change in walking duration between before and during the lockdown) is summarised with sample size (n), Mann-Whitney paired test-statistic (V) and significance levels (p); Table S3: Multivariable logistic regression model results for dog’s reduction of total weekly dog walking duration (compared to stayed the same or increased) during the first UK COVID-19 lockdown (March/April 2020) before the backward elimination was used to identify significant variables. The model was run on 486 observations, X2 = 18.14, p = 0.32, Pseudo R2 (Cragg-Uhler) = 0.053, AIC = 588.23; Table S4: Multivariable regression analysis of variables associated with duration of person’s dog walking before the first UK COVID-19 lockdown (March/April 2020). The model is based on 511 observations, F(22) = 7.63, p = 0.00, Cragg-Uhler Pseudo-R2 = 0.21, AIC = 396.60; Table S5. Multivariable logistic regression model results for person’s reduction of total weekly dog walking duration (compared to stayed the same or increased) during the first UK COVID-19 lockdown (March/April 2020) before the backward elimination was used to identify significant variables. The model was run on 491 observations, X2 = 25.92, p = 0.13, Pseudo R2 (Cragg-Uhler) = 0.074, AIC = 601.06.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W., T.M.G. and S.C.O.-G.; methodology, C.W., T.M.G., S.C.O.-G. and D.C.A.; formal analysis, S.C.O.-G. and T.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.O.-G., C.W. and T.M.G.; writing—review and editing, C.W., T.M.G., S.C.O.-G. and D.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Liverpool (VREC957 24 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

As free-text boxes may contain data enabling participant identification, data is not freely available.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the research participants who completed this survey.

Conflicts of Interest

S.C.O.-G. is a salaried employee of Dogs Trust, a dog welfare organisation. Dogs Trust had no input into this research. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Christian, H.E.; Westgarth, C.; Bauman, A.; Richards, E.A.; Rhodes, R.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Mayer, J.A.; Thorpe, R.J. Dog Ownership and Physical Activity: A Review of the Evidence. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G.N.; Allen, K.; Braun, L.T.; Christian, H.E.; Friedmann, E.; Taubert, K.A.; Thomas, S.A.; Wells, D.L.; Lange, R.A. Pet Ownership and Cardiovascular Risk: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Jewell, C.; German, A.J.; Boddy, L.M.; Christian, H.E. Dog owners are more likely to meet physical activity guidelines than people without a dog: An investigation of the association between dog ownership and physical activity levels in a UK community. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E. I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E. Functional and recreational dog walking practices in the UK. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 36, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, A.J.; Blackwell, E.; Evans, M.; Westgarth, C. Overweight dogs exercise less frequently and for shorter periods: Results of a large online survey of dog owners from the UK. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, E.; German, A.J.; Blackwell, E.; Evans, M.; Westgarth, C. Variation in activity levels amongst dogs of different breeds: Results of a large online survey of dog owners from the UK. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E. The Responsible Dog Owner: The Construction of Responsibility. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Christian, H.E. How might we increase physical activity through dog walking?: A comprehensive review of dog walking correlates. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UKGOV. Staying at Home and Away from Others (Social Distancing); UKGOV: London, UK, 2020.

- Jenkins, R.; Burke, D. Coronavirus: You Can Only Walk Your Dog Once a Day during Lockdown 2020. Daily Mirror, 25 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shennan, R. Can I Walk My Dog during Lockdown? The UK Coronavirus Rules for Pets, Explained. INEWS, 5 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goverment. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Advice for People in England with Animals 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-people-with-animals. (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- GOV.SCOT. Coronavirus (COVID-19): Advice for Animal Owners; GOV.SCOT: Edinburgh, Scotland. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-animal-owners/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Ni, G. COVID-19 Horses and Pets Guidance Department for Agriculture; DAERA: Belfast, UK, 2020.

- Dogs Trust. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown Restrictions on Dogs & Dog Owners in the UK; Dogs Trust: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, K.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Anderson, K.L.; Casey, R.A.; Christley, R.M.; Harris, L.; McMillan, K.M.; Mead, R.; Murray, J.K.; Samet, L.; et al. “More Attention than Usual”: A Thematic Analysis of Dog Ownership Experiences in the UK during the First COVID-19 Lockdown. Animals 2021, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoesmith, E.; Shahab, L.; Kale, D.S.; Mills, D.; Reeve, C.; Toner, P.; de Assis, L.S.; Ratschen, E. The Influence of Human–Animal Interactions on Mental and Physical Health during the First COVID-19 Lockdown Phase in the U.K.: A Qualitative Exploration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratschen, E.; Shoesmith, E.; Shahab, L.; Silva, K.; Kale, D.; Toner, P.; Reeve, C.; Mills, D.S. Human-animal relationships and interactions during the COVID-19 lockdown phase in the UK: Investigating links with mental health and loneliness. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, J.L.; Johnston, K.L. Puppy love in the time of Corona: Dog ownership protects against loneliness for those living alone during the COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Moore, S.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, R. Dogs Unleashed: The Positive Role Dogs Play during COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.; García, E.; Darder, P.; Argüelles, J.; Fatjó, J. The effects of the Spanish COVID-19 lockdown on people, their pets, and the human-animal bond. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christley, R.M.; Murray, J.K.; Anderson, K.L.; Buckland, E.L.; Casey, R.A.; Harvey, N.D.; Harris, L.; Holland, K.E.; McMillan, K.M.; Mead, R.; et al. Impact of the First COVID-19 Lockdown on Management of Pet Dogs in the UK. Animals 2021, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszar, A.; Jakab, F.; Valencak, T.G.; Lanszki, Z.; Tóth, G.E.; Kemenesi, G.; Tarantini, S.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Ungvari, Z. Companion animals likely do not spread COVID-19 but may get infected themselves. GeroScience 2020, 42, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Rivas-García, L.; Quiles, J.L.; Redondo-Sánchez, D.; Aranda-Ramírez, P.; Llopis-González, J.; Pérez, M.J.S.; Sánchez-González, C. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain: Hygiene habits, sociodemographic profile, mobility patterns and comorbidities. Environ. Res. 2020, 192, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human–dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaechter, S.; Starmer, C.; Tufano, F. Measuring the Closeness of Relationships: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the ‘Inclusion of the Other in the Self’ Scale. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFollette, M.R.; Rodriguez, K.E.; Ogata, N.; O’Haire, M.E. Military Veterans and Their PTSD Service Dogs: Associations Between Training Methods, PTSD Severity, Dog Behavior, and the Human-Animal Bond. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutt, H.E.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M.W.; Pikora, T.J. Physical Activity Behavior of Dog Owners: Development and Reliability of the Dogs and Physical Activity (DAPA) Tool. J. Phys. Act. Health 2008, 5, S73–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holle, V.; de Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; van Cauwenberg, J.; van Dyck, D. Assessment of physical activity in older Belgian adults: Validity and reliability of an adapted interview version of the long International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-L). BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Package R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, A. Mann-Whitney test is not just a test of medians: Differences in spread can be important. BMJ 2001, 323, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 2014, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. The Hottest Commodity in Quebec: A Dog That Needs Walking After 8 p.m. CtV News, 7 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, Z.S.; Aunan, K.; Chowdhury, S.; Lelieveld, J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18984–18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussolari, C.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Packman, W.; Kogan, L.; Erdman, P. “I Couldn’t Have Asked for a Better Quarantine Partner!”: Experiences with Companion Dogs during Covid-19. Animals 2021, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.; Pritchard, R.; Nottle, C.; Banwell, H. Pets, touch, and COVID-19: Health benefits from non-human touch through times of stress. J. Behav. Econ. Policy 2020, 4, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, J.W.; Adams, B.L.; Eliasson, M.N.; Zsembik, B.A.; McDonald, S.E. How pets factor into healthcare decisions for COVID-19: A One Health perspective. One Health 2020, 11, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, H.A.; Scammon, D.L. No Pet Left Behind: Accommodating Pets in Emergency Planning. J. Public Policy Mark. 2007, 26, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, S.A. The COVID-19 pandemic: Emerging perspectives and future trends. J. Public Health Res. 2020, 9, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, C.A.; Mistry, R.D. Dog Bites in Children Surge during Coronavirus Disease-2019: A Case for Enhanced Prevention. J. Pediatr. 2020, 225, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulloch, J.S.P.; Minford, S.; Pimblett, V.; Rotheram, M.; Christley, R.M.; Westgarth, C. Paediatric emergency department dog bite attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic: An audit at a tertiary children’s hospital. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS-Digital. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England, 2019. NHS-Digital, 8 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- RSPCA. We Welcome New England Guidance on Dog Walking in Lockdown 2021. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/-/news-new-england-dog-walk-covid-guidance-welcomed (accessed on 20 January 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).