Prevalence of Suicide Thoughts and Behaviours among Female Garment Workers Who Survived the Rana Plaza Collapse: An In-Depth Inquiry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Gender, Socio-Economic, and Cultural Settings in Shaping Suicidal Ideation

P09: “I am struggling with poverty since the collapse because I am a woman. I am not allowed to do many jobs that a survived male worker can easily do. I have lost every hope to survive.”

P02: “Many of my male co-workers have become rickshaw puller, van driver, and day labour. I can neither be a rickshaw puller or van driver because our society will not allow/accept me to do that. I am fed up of struggling with my fate and want to end up with it.”

P08: “After the collapse, I tried to find a job in the garment sector but the management of a factory did not hire me as they believed, being a female worker and having a history of injuries, I will not be able to fulfil the daily production target. Since then I am unemployed. I do not find any value of my life and I am greatly depressed…”

3.2. Ongoing Physical Injuries/Disability, and Mental Trauma Linked to Suicidal Ideation

P11: “Recently, doctors suggested me to be ready for an operation to amputate my right leg to stop further infections sourced from Rana Plaza collapse. I am worried about the rest part of my life without one leg.”

P01: “Since the collapse, I have been living with severe headaches, shoulder, backbone, and leg pain… I cannot tolerate these pain and sometimes I want to kill myself.”

P05: “I cannot sleep well due to the muscle pain sourced from the collapse of Rana Plaza. No free treatment is available now for us. Sometimes, the pain becomes unbearable which makes me upset about life and I wish to finish it.”

P02: “My husband is a day labour who earns BDT 350/400 ($3.50/4.50) per day. I always live with the fear if he does not feed me anymore and gets married to another woman. How long a man can feed a disabled woman?”

P04: “My husband left me last year due to my disability. I am not connected to anyone. I feel like I do not exist anymore and I do not find the value in living further.”

P10: “Life has become meaningless to me as I have become disabled to work to support myself and my family.”

3.3. The Feeling of ‘Being a Burden’ Linked to Suicidal Ideation

P03: “I started to work in the RMG sector as my father was too old to work as a day labour. My little siblings and parents relied on my income when I worked at Rana Plaza. As I have become unable to work after the collapse, my old father has started to work again. It is better to die than living as a burden, at least, my family will be freed from feeding me.”

P01: “Once, I was the main earning person and every member of my family used to respect me. Unfortunately, I have become a burden for them. Now, my family is suffering a lot to feed me and to buy medicines for me. I just cannot tolerate this painful life and I do not want this life anymore…”

3.4. Lack of Social Support and Social Stigma Leading to Suicidal Ideation

P06: “I and my elder sister, who found as a spot dead, worked in the same factory at Rana Plaza. I cannot forget my sister’s dead face till today…I am living with trauma! My father died a few years ago. Our relatives now drive us away! Our family is treated as a ‘cursed family’ within the community...”

P07: “My husband died in 2009 in a road accident which led me to join in RMG work for survival. After being rescued from the collapse, I and my daughter were living as self-isolated in our previous rented house in Jamsing (a residential area in Savar, Dhaka) because we were not treated well by our neighbours. Our neighbours used to treat me as ALOKKHI (a euphemism for loss/bad luck) if anything unexpected happened in their daily lives. We shifted to a new area where I now have started a small grocery shop with the financial assistance received from different sources after the collapse. I hide the information that I am one of the Rana Plaza survivors.”

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferdous, F. Dreams Incomplete: Rana Plaza Hero Himu Dies by Suicide. 2019. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/news/dreams-incomplete-1734946 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- The Daily Star. Rana Plaza Volunteer Sets Himself on Fire and Dies. 2019. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/country/news/youth-commits-suicide-savar-1734577 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Bangla News 24.com. Rana Plaza Victim Commits Suicide. 2014. Available online: https://www.banglanews24.com/english/national/news/bd/15128.details (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Mamun, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D. PTSD-related suicide six years after the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, H.; Maple, M.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. The current health and wellbeing of the survivors of the Rana plaza building collapse in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fitch, T.J.; Moran, J.; Villanueva, G.; Sagiraju, H.K.R.; Quadir, M.M.; Alamgir, H. Prevalence and risk factors of depression among garment workers in Bangladesh. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2017, 63, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terayama, T.; Shigemura, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kurosawa, M.; Nagamine, M.; Toda, H.; Yoshino, A. Mental health consequences for survivors of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster: A systematic review. CNS Spectr. 2021, 26, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, A.M.; Alexander, D.A.; Klein, S. Survivors of the Piper Alpha oil platform disaster: Long-term follow-up study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N.; Kameoka, S.; Kato, H.; You, Y. Long-term psychological consequences among adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake in China: A cross-sectional survey six years after the disaster. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 204, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnberg, F.K.; Johannesson, K.B.; Michel, P.O. Prevalence and duration of PTSD in survivors 6 years after a natural disaster. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chou, F.H.C.; Wu, H.C.; Chou, P.; Su, C.Y.; Tsai, K.Y.; Chao, S.S.; Chen, M.C.; Su, T.P.; Sun, W.J.; Ou-Yang, W.C. Epidemiologic Psychiatrytric studies on post-disaster impact among Chi-Chi earthquake survivors in Yu-Chi, Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 61, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Spialek, M.L. Suicide ideation and a post-disaster assessment of risk and protective factors among Hurricane Harvey survivors. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, H.; Fu, M.; Han, Z.; Qu, Z.; Wang, X.; Guan, L. Suicidality associated with PTSD, depression, and disaster recovery status among adult survivors 8 years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 253, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, C.; Kong, D.; Solomon, P.; Fu, M. The relationship between PTSD and suicidality among Wenchuan earthquake survivors: The role of PTG and social support. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 235, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, O.; Boysan, M.; Ozdemir, P.G.; Yilmaz, E. Relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociation, quality of life, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among earthquake survivors. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. Profit over life: Industrial disasters and implications for labor and gender. In Social Justice in the Globalization of Production; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, H.; Maple, M.; Fatema, S.R. Vulnerabilities of women workers in the readymade garment sector of Bangladesh: A case study of Rana Plaza. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2018, 19, 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Mashreky, S.R.; Rahman, F.; Rahman, A. Suicide kills more than 10,000 people every year in Bangladesh. Arch. Suicide Res. 2013, 17, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, S.S.; Alonge, O.; Islam, M.I.; Hoque, D.M.E.; Wadhwaniya, S.; Ul Baset, M.K.; El Arifeen, S. The burden of suicide in rural Bangladesh: Magnitude and risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naved, R.T.; Akhtar, N. Spousal violence against women and suicidal ideation in Bangladesh. Women’s Health Issue 2008, 18, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Imam, S.Z.; Jing, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C. Suicide attempt and its associated factors amongst women who were pregnant as adolescents in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, C.A.; Shahnaz, A.; Simkhada, P. High rates of suicide and violence in the lives of girls and young women in Bangladesh: Issues for feminist intervention. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arcara, J. Domestic Violence and Suicide among Women in Dhaka Division. MPH Dissertation, Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH), Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005. (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.R.; Ratele, K.; Helman, R.; Dlamini, S.; Makama, R. Masculinity and suicide in Bangladesh. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakken, N.W.; Gunter, W.D. Self-cutting and suicidal ideation among adolescents: Gender differences in the causes and correlates of self-injury. Deviant Behav. 2012, 33, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.; Milner, A.; Maple, M. Women and suicide: Beyond the gender paradox. Int. J. Cul. Ment. Health 2014, 7, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comyns, B.; Franklin-Johnson, E. Corporate reputation and collective crises: A theoretical development using the case of Rana Plaza. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R. Rana Plaza fieldwork and academic anxiety: Some reflections. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Rahman, A.; Mashreky, S.R.; Humaira, T.; Dalal, K. Rescue and emergency management of a man-made disaster: Lesson learnt from a collapse factory building, Bangladesh. Sci. World J. 2015, 2015, 136434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berman, D.M. Organizing for better lives. Mon. Rev. 2016, 68, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, G. Bangladesh: Currently the worst, but possibly the future’s best. New Solut. 2015, 24, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatema, S.R. Women’s health-related vulnerabilities in natural disaster-affected areas of Bangladesh: A mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Fatema, S.R.; Hoque, S.; Ara, J.; Maple, M. Risks of HIV/AIDS transmission: A study on the perceptions of the wives of migrant workers of Bangladesh. J. Int. Womens Stud. 2020, 21, 450–471. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Remember Rana Plaza: Bangladesh’s Garment Workers Still Need Better Protection. 2018. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/04/24/remember-rana-plaza# (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Kabir, H. A Gendered Analysis of Reactions to the Recent Bangladeshi Garment Factory Disaster. Master’s Dissertation, The University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Action Aid. Six Years on from Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza Tragedy, One in Five Survivors’ Health Is Deteriorating. 2019. Available online: https://actionaid.org/news/2019/six-years-bangladeshs-rana-plaza-tragedy-one-five-survivors-health-deteriorating (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). The Rana Plaza Accident and Its Aftermath. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/geip/WCMS_614394/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Institute for Global Labour and Human Rights. Rana Plaza: A Look Back, and Forward. 2014. Available online: http://www.globallabourrights.org/alerts/rana-plaza-bangladeshanniversary-a-look-back-and-forward (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Richards, J.; Rahman, L.; Huda, N. Rana Plaza Three Years After: Physical and Mental Morbidities among Survivors. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Public Health, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 28–29 July 2016; The International Institute of Knowledge Management (TIIKM): Nugegoda, Sri Lanka, 2016; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, T.; Villanueva, G.; Quadir, M.M.; Sagiraju, H.K.; Alamgir, H. The prevalence and risk factors of post-traumatic stress disorder among workers injured in Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015, 58, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkovics, N.; Hoque, S.F.; Sinkovics, R.R. Rana Plaza collapse aftermath: Are CSR compliance and auditing pressures effective? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 617–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, J.; Uddin, S. Human rights disasters, corporate accountability and the state: Lessons learned from Rana Plaza. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Maple, M.; Usher, K.; Islam, M.S. Health vulnerabilities of readymade garment (RMG) workers: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, A.; Solaiman, S.M. Rana disaster: How far can we proceed with CSR? J. Financ. Crime 2016, 23, 748–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin, I.M. Who is to blame? A re-examination of fast fashion after the 2013 factory disaster in Bangladesh. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2014, 10, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, M.; Frey, L.M.; McKay, K.; Coker, S.; Grey, S. “Nobody hears a silent cry for help”: Suicide attempt survivors’ experiences of disclosing during and after a crisis. Arch. Suicide Res. 2020, 24, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

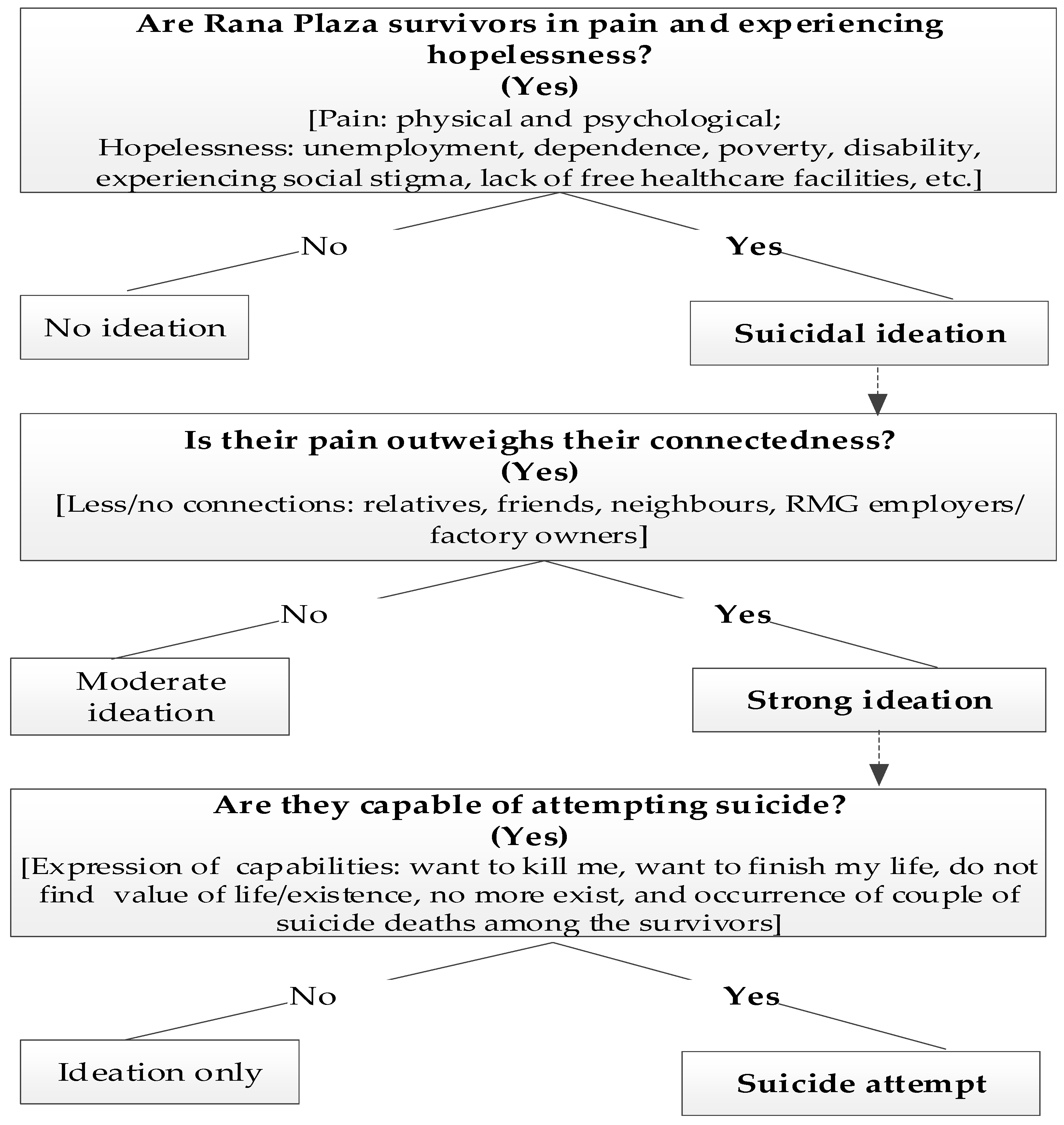

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackstone, A. Principles of Sociological Inquiry–Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; Saylor Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes in qualitative data. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shneidman, E.S. The Suicidal Mind; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M.; Saffer, B.Y. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, R.; Scourfield, J.; Moore, G. Gender, relationship breakdown, and suicide risk: A review of research in Western countries. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 2239–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woo, J.M.; Postolache, T.T. The impact of work environment on mood disorders and suicide: Evidence and implications. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2008, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franklin, J.; Ribeiro, J.; Fox, K.; Bentley, K.; Kleiman, E.; Huang, X.; Knock, M. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.; Oh, W.O.; Suk, M. Risk factors for suicide ideation among adolescents: Five-year national data analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greydanus, D.E.; Calles, J., Jr. Suicide in children and adolescents. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2007, 34, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Jung-Choi, K.; Jun, H.J.; Kawachi, I. Socioeconomic inequalities in suicidal ideation, parasuicides, and completed suicides in South Korea. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iemmi, V.; Bantjes, J.; Coast, E.; Channer, K.; Leone, T.; McDaid, D.; Lund, C. Suicide and poverty in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Suicide-Key Facts. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=B88A4A835F703C0B7C34D270EC1E2FAA?sequence=1 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Arafat, S.Y.; Mohit, M.A.; Mullick, M.S.; Kabir, R.; Khan, M.M. Risk factors for suicide in Bangladesh: Case–control psychological autopsy study. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, H.; Maple, M.; Usher, K. The impact of COVID-19 on Bangladeshi readymade garment (RMG) workers. J. Public Health 2021, 43, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes | Identified Issues |

|---|---|

| Gender, socio-economic, and cultural settings in shaping suicidal ideation |

|

| Ongoing physical injuries/disability, and mental trauma linked to suicidal ideation |

|

| The feeling of ‘being a burden’ linked to suicidal ideation |

|

| Lack of social support and social stigma leading to suicidal ideation |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kabir, H.; Maple, M.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Prevalence of Suicide Thoughts and Behaviours among Female Garment Workers Who Survived the Rana Plaza Collapse: An In-Depth Inquiry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126326

Kabir H, Maple M, Islam MS, Usher K. Prevalence of Suicide Thoughts and Behaviours among Female Garment Workers Who Survived the Rana Plaza Collapse: An In-Depth Inquiry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126326

Chicago/Turabian StyleKabir, Humayun, Myfanwy Maple, Md Shahidul Islam, and Kim Usher. 2021. "Prevalence of Suicide Thoughts and Behaviours among Female Garment Workers Who Survived the Rana Plaza Collapse: An In-Depth Inquiry" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126326

APA StyleKabir, H., Maple, M., Islam, M. S., & Usher, K. (2021). Prevalence of Suicide Thoughts and Behaviours among Female Garment Workers Who Survived the Rana Plaza Collapse: An In-Depth Inquiry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6326. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126326