“If You Don’t See the Dog, What Can You Do?” Using Procedures to Negotiate the Risk of Dog Bites in Occupational Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

Managing Risk through Procedures

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Approach

2.2. Description of Study Sites

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Participant Recruitment

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

3.2. Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Surveillance of Dogs– Identifying Hazards

“He’ll lift his paw, he lies on his back, and it’s just him being him (…) I know that I can still touch him when he’s doing that (…) but if anybody else went in that kennel, they’d probably be like, “Shit, I’m not going anywhere near this dog,” because he’s showing every sign that he doesn’t want you to go and attach the lead”.Annie, Dog Shelter.

“The worse dogs are those that give no affection – you know, a dog that’s not being funny with you, but also not being nice. “What do you think!? Just give me something!””Alice, Dog Shelter.

“When you’re [delivering mail or parcels] (…) you risk assess in your mind every property that you go to. You’re listening out for any slight noise. You’re looking for any indication that there’s a dog. (…)”Ben, Delivery Company.

“Any animal that poses a threat while attempting to deliver or collect mail [or parcels]. Including:

Any dog or animal which: has attacked previously, (…) is restrained to avoid contact with delivery staff due to the likelihood (…) attack, (…) is roaming in its garden/ territory that presents a risk of attack (…), that shows aggression to other dogs or human, (…) that the delivery staff are uncomfortable with, (…) dogs behind letter boxes snapping at letters during delivery (…)”.Delivery Company.

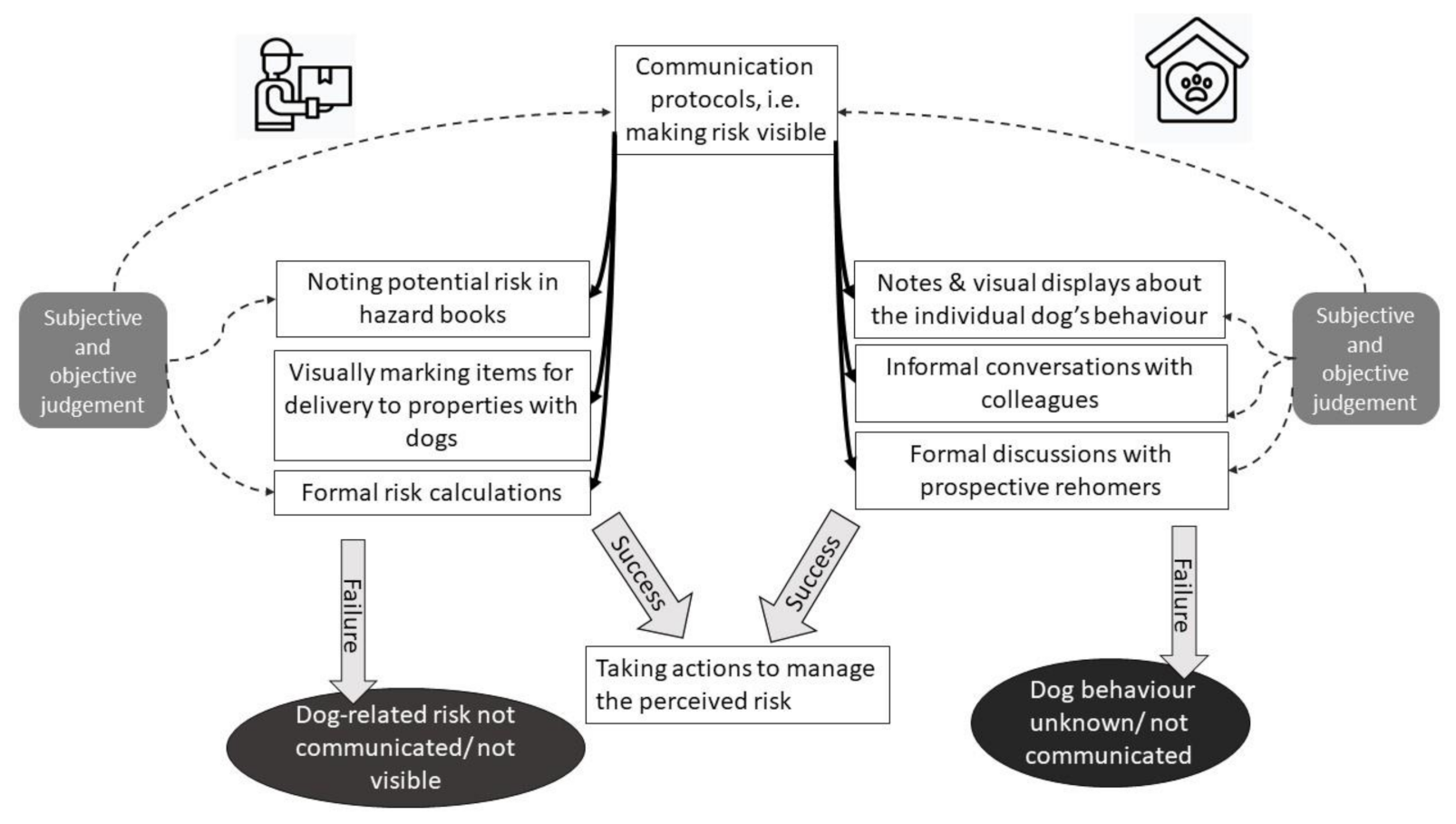

3.2.2. Communicating Risk to Others

“(…) One box measured the perceived severity of an individual dog attack [on a scale 1–10] and the second (…) box measured the likelihood of an attack from the same animal. (…).”Adam, Delivery Company.

“I think that there was a miscommunication of how aggressive this dog was. And the nurse went in to go and get the dog out of the kennel (…) that’s when the dog attacked the nurse.”Amy, vet nurse Dog Shelter.

3.2.3. Actions taken to manage perceived risk

“If they don’t like the vets, we’ll build up things slowly. (…) We would just go into the [vet] room, feed the dog, take him back out, (…) and then eventually, you would maybe touch his ears (…). Maybe then slowly introduce a stethoscope (…), and then probably introduce the vet or the vet nurses.”Nick, Dog Shelter.

“It’s never, “Oh, it bit one person.” (…) It means this dog is really not rehomeable. It’s aggressive. Its welfare is not good. It’s a big picture. (…) We (…) [members of staff involved in dog training, day-to-day care and veterinary treatment ]have to agree. It’s a massive process.”Isabel, Dog Shelter.

“You’ve got to think of the centre as well, because everything is now recorded. Every bite. Every bark. (…) And if that dog went out and caused trouble, there is a paper trail right back to us. And in this day and age with people suing each other, it’s just not worth the risk. You could lose your centre, your reputation (…)”Matt, Dog Shelter.

“We had a guy (…) who’d been bitten by a dog, but continued to interact with dogs. (…). I had to say to him, “Look, you can’t do it.” I said, “(…) You’re at risk and you put others at risk. You’re putting yourself in a situation where the [organisation] will frown on you, if you get bitten. You’re paid to deliver [items] not (…) to go stroke a dog.”Frank, Delivery Company.

“If you go on (…) the [organisations portal], there are hundreds, if not thousands, of safety documents. Sometimes, the frontline staff, the managers, the reps don’t know where to go with it.”Frank, Delivery Company.

3.2.4. Reporting Bites and Near-Misses

“When Moon got me, we did an accident instead of a bite report, because he didn’t really mean it, he just was like, “Ah,” because obviously he was in quite a lot of pain”Amy, Dog Shelter.

“I didn’t [report the bite]. (…) the only walk it gets in a day is at 5 o’clock in the morning, so I know it’s not a danger to the public. So I thought, “I don’t really want to be responsible for a dog getting put to sleep.””Georgia, Delivery Company.

“I think (…) people think “Oh, he wouldn’t do that to me,” or, “They must’ve done something wrong.” (…) there can be quite a blame game”,Eli, Dog Shelter.

3.2.5. Investigating bites and near-misses

“[T]hey just tell you about reporting things, but nothing ever comes out of it; no lessons are learnt, or procedures changed”,Rita, Dog Shelter.

“We didn’t go in great depths of whose fault was it, and who should have done this, [or] that. I think it’s just something that you don’t really talk about, because everyone sort of works well with each other.”Clair, veterinary nurse at a Dog Shelter.

“It’s supposed to be [thorough] investigation. In my opinion, it’s usually Inspector Clouseau who does it. (…). It’s trying to attach a blame to somebody, rather than it just being a freak accident”Cameron, Delivery Company.

3.2.6. Learning and Teaching Safety

“You can’t learn everything from [work training]. (…) And I suppose like, when you’re [i]n the [kennels], you do get to speak with people, and you do get to learn what they’ve been doing (…)”Freya, Dog Shelter.

“I think definitely after you have been bitten or had an incident, it does make you a lot more mindful and it really helps you to see how a dog can progress to a certain thing.”Amy, Dog Shelter.

“It’s a rushed message. (…) Then, there’s a queue because, when you’ve had the message, you’ve got to sign to say you’ve had it. (…) So they sign the sheet before they’ve had the message.”Cameron, Delivery Company.

4. Discussion

4.1. Preventing Work Incidents vs. Preventing Dog Bites

4.2. Differences in Perceptions of Risk

4.3. Is Safety just a Lack of Risk?

4.4. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Haire, M. Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead. J. Vet. Behav. 2010, 5, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajshekar, M.; Blizzard, L.; Julian, R.; Williams, A.-M.; Tennant, M.; Forrest, A.; Walsh, L.J.; Wilson, G. The incidence of public sector hospitalisations due to dog bites in Australia 2001-2013. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.M.; Hopster, H. Dog bites in The Netherlands: A study of victims, injuries, circumstances and aggressors to support evaluation of breed specific legislation. Vet. J. 2010, 186, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Sharma, S.; Agarwal, A.; Ingle, G.K. Prevalence of dog bites in rural and urban slums of Delhi: A community-based study. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loder, R.T. The demographics of dog bites in the United States. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, J.S.P.; Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Fleming, K.M.; Vivancos, R.; Westgarth, C. English hospital episode data analysis (1998–2018) reveal that the rise in dog bite hospital admissions is driven by adult cases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Brooke, M.; Christley, R.M. How many people have been bitten by dogs? A cross-sectional survey of prevalence, incidence and factors associated with dog bites in a UK community. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, J. Admission Caused by Dogs and Other Mammals. NHS Digital; 2015. Available online: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/h/6/animal_bites_m12_1415.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2016).

- Drudi, D.; Are animals occupational hazards? Bureau of Labor Statistics. Compensation and Working Conditions Fall 2000, 15–22. 2000. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/cwc/are-animals-occupational-hazards.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Oliveira, E.A.D.; Manosso, R.M.; Braune, G.; Marcenovicz, P.C.; Kuritza, L.N.; Ventura, H.L.B.; Paploski, I.A.D.; Kikuti, M.; Biondo, A.W. Neighborhood and postal worker characteristics associated with dog bites in postal workers of the Brazilian National Postal Service in Curitiba. Ciencia Saude Coletiva 2013, 18, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, S.C.; Tang, F.C.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, C.T.; Yen, C.H.; Lee, M.C. An epidemiologic study of dog bites among postmen in central Taiwan. Chang. Gung Med J. 2000, 23, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.; Christley, R.; Watkins, F.; Yang, H.; Bishop, B.; Westgarth, C. Dog bite safety at work: An injury prevention perspective on reported occupational dog bites in the UK. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, G. Inquiry into Dog Attacks on Postal Workers; The Royal Mail Group: Lodon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fritschi, L.; Day, L.; Shirangi, A.; Robertson, I.; Lucas, M.; Vizard, A. Injury in Australian veterinarians. Occup. Med. 2006, 56, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landercasper, J.; Cogbill, T.H.; Strutt, P.J.; Landercasper, B.O. Trauma and the Veterinarian. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 1988, 28, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BVA. BVA Promotes Guidance as Survey Reveals over Half of Farm Vets Injured at Work; BVA: Lodon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, M.; Martens, P.J.; Chateau, D.; Burchill, C. Effectiveness of breed-specific legislation in decreasing the incidence of dog-bite injury hospitalisations in people in the Canadian province of Manitoba. Inj. Prev. 2012, 19, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedon, N.; Ó’Súilleabháin, P.S. Dog bite injuries to humans and the use of breed-specific legislation: A comparison of bites from legislated and non-legislated dog breeds. Ir. Vet. J. 2017, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Súilleabháin, P. Ó Human hospitalisations due to dog bites in Ireland (1998–2013): Implications for current breed specific legislation. Vet. J. 2015, 204, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, B.; García-Belenguer, S.; León, M.; Palacio, J. Spanish dangerous animals act: Effect on the epidemiology of dog bites. J. Vet. Behav. 2007, 2, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilson, F.; Damsager, J.; Lauritsen, J.; Bonander, C. The effect of breed-specific dog legislation on hospital treated dog bites in Odense, Denmark—A time series intervention study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, B.; Buckley, J.; Esmail, A. Does the Dangerous Dogs Act protect against animal attacks: A prospective study of mammalian bites in the Accident and Emergency department. Injury 1996, 27, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, S. Breed-specific legislation and the pit bull terrier: Are the laws justified? J. Vet. Behav. 2006, 1, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, L.M.; Barber, R.T.; Wynne, C.D.L. A canine identity crisis: Genetic breed heritage testing of shelter dogs. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Súilleabháin, P.; Doherty, N. Epidemiology of dog bite injuries: Dog-breed identification and dog-owner interaction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 68, 1157–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.L.; Harrison, N.; Wolff, L.; Westgarth, C. Is That Dog a Pit Bull? A Cross-Country Comparison of Perceptions of Shelter Workers Regarding Breed Identification. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2014, 17, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.Y.; Paterson, M.B.A.; Phillips, C.J.C. Breed Group Effects on Complaints about Canine Welfare Made to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) Queensland, Australia. Animals 2019, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patronek, G.; Twining, H.; Arluke, A. Managing the stigma of outlaw breeds: A case study of pit bull owners. Soc. Anim. 2000, 8, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, L.M.; Barber, R.T.; Wynne, C.D. What’s in a Name? Effect of Breed Perceptions & Labeling on Attractiveness, Adoptions & Length of Stay for Pit-Bull-Type Dogs. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146857. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen, S.; Almklov, P.; Fenstad, J. Reducing the gap between procedures and practice lessons from a successful safety intervention. Saf. Sci. Monit. 2008, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Veltkamp, G.; Brown, P. The everyday risk work of Dutch child-healthcare professionals: Inferring ‘safe’and ‘good’parenting through trust, as mediated by a lens of gender and class. Sociol. Health Illn. 2017, 39, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N. Postmodern reflections on ‘risk’, ‘hazards’ and life choices. In Risk and Sociocultural Theory New Directions and Perspectives; Lupton, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution Ofsociety; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lautman, L.; Gallimore, P. Control of crew-caused accidents. Air Line Pilots Assoc. 1987, 40, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, J. Engineering a safety culture. In Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S. Failure to adapt or adaptations that fail: Contrasting models on procedures and safety. Appl. Ergon. 2003, 34, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S. The bureaucratization of safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Introduction: Risk and sociocultural theory. In Risk and Sociocultural Theory: New Directions and Perspectives; Lupton, D., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, L.; Clarke, J.A.; Cullen, K.; Bielecky, A.; Severin, C.; Bigelow, P.L.; Irvin, E.; Culyer, A.; Mahood, Q. The effectiveness of occupational health and safety management system interventions: A systematic review. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay-Williams, R.; Colligan, L. Back to basics: Checklists in aviation and healthcare. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, M. The Risk Management of Everything; Demos: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi, S. Translating Knowledge While Mending Organisational Safety Culture. Risk Manag. 2004, 6, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Doing Visual Ethnography; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Thorogood, N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, G.E. Multi-sited ethnography: Five or six things I know about it now. In Multi-Sited Ethnography: Problems and Possibilities in the Translocation of Research Methods; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2011; pp. 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. The methodological position of symbolic interactionism. Sociol. Thought Action 1969, 2, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castleberry, A. NVivo 10 [software program]. Version 10; QSR International: Doncaster, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Society. Risk: Analysis, Perception and Management; Report of a Royal Society study group; Royal Society: Lodon, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dien, Y.; Llory, M.; Montmayeul, R. Organisational accidents investigation methodology and lessons learned. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 111, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSE. Management of risk when planning work: The right priorities. Available online: http://wwwhsegovuk/construction/lwit/assets/downloads/hierarchy-risk-controlspdf (accessed on 16 March 2019).

- Reason, J. Safety paradoxes and safety culture. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2000, 7, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.; Ateah, C.; Secco, L. Living in a World of Our Own: The Experience of Parents Who Have a Child With Autism. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Rouse, J.; Godbole, M.; Wells, H.L.; Boppana, S.; Schwebel, D.C. Systematic Review: Interventions to Educate Children About Dog Safety and Prevent Pediatric Dog-Bite Injuries: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 42, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.; Christley, R.; Westgarth, C. Risk factors for dog bites-an epidemiological perspective. In Dog Bites: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; 5m Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2017; pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- DeCamp, W.; Herskovitz, K. The Theories of Accident Causation. Security Supervision and Management 2015, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Gray, G.C. Socially constructing safety. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, J.O. Heading into the unknown: Everyday strategies for managing risk and uncertainty. Health Risk Soc. 2008, 10, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviews | Focus Group Discussion |

|---|---|

| How did you start working here? What, if any, are the biggest risks in your day to day work? What happened when you were bitten by a dog? How, if at all, did a bite affect your work? Is there anything that you do to stay safe around dogs? If so, could you provide an example of something that you do? | Has anyone here been bitten by a dog? Are there any dangerous aspects of your job? If so, what are they? What happened when you were bitten by a dog? How, if at all, do you prevent bites at work? How do you teach someone to be safe around dogs at work? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Christley, R.M.; Watkins, F.; Yang, H.; Westgarth, C. “If You Don’t See the Dog, What Can You Do?” Using Procedures to Negotiate the Risk of Dog Bites in Occupational Contexts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147377

Owczarczak-Garstecka SC, Christley RM, Watkins F, Yang H, Westgarth C. “If You Don’t See the Dog, What Can You Do?” Using Procedures to Negotiate the Risk of Dog Bites in Occupational Contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(14):7377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147377

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwczarczak-Garstecka, Sara C., Robert M. Christley, Francine Watkins, Huadong Yang, and Carri Westgarth. 2021. "“If You Don’t See the Dog, What Can You Do?” Using Procedures to Negotiate the Risk of Dog Bites in Occupational Contexts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 14: 7377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147377

APA StyleOwczarczak-Garstecka, S. C., Christley, R. M., Watkins, F., Yang, H., & Westgarth, C. (2021). “If You Don’t See the Dog, What Can You Do?” Using Procedures to Negotiate the Risk of Dog Bites in Occupational Contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7377. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147377