Family Recovery Interventions with Families of Mental Health Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

“…a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even within the limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness” [4] (p. 21).

1.1. Context to Family Recovery in Ireland

1.2. Importance of Inclusion of Families

1.3. Rationale for Systematic Review

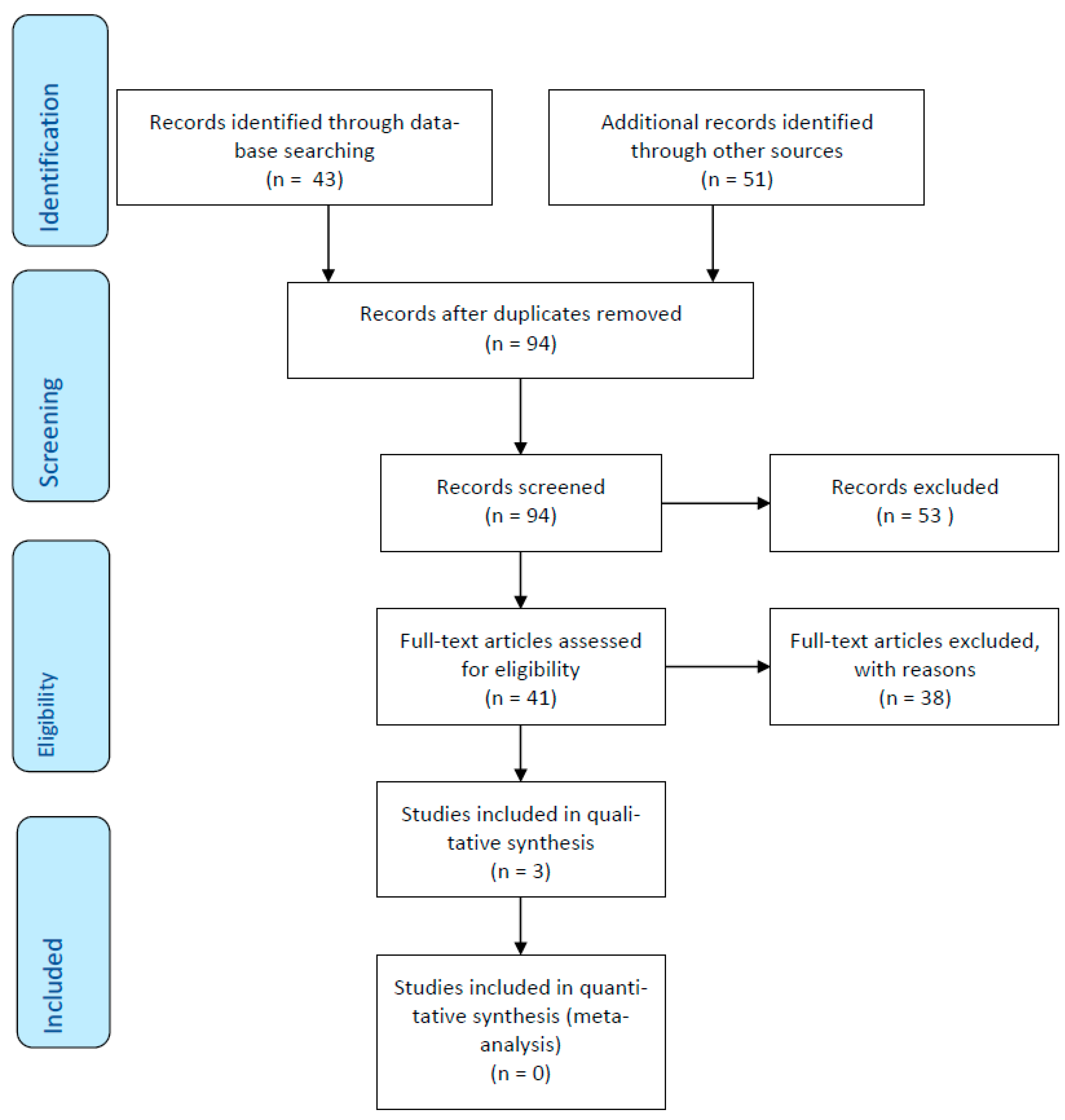

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4.1. Screening

2.4.2. Data Collection and Extraction

2.4.3. Assessing the Risk of Bias

2.4.4. Assessing the Quality of Evidence

2.4.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Family Recovery Initiatives

3.2. Benefits

3.2.1. Education

“I’d say, this is a bit silly but I like, I quite like the games and like the easier way of understanding it.” [51]

“When I started the Kidstime project, I felt like I couldn’t really express myself, because I know that people often thought that because my mum had mental illness I may have mental illness, so I didn’t want to say anything, because I didn’t want to seem odd or say anything inappropriate, so I kept to myself. So when I started coming to this project, you realize that, not necessarily, because when you know that other people have the same problems as you, and they look normal, they seem normal, that’s its okay to come out and just, you know, express yourself a bit more. So I just felt like I wouldn’t necessarily, after learning about the illness I felt like I wouldn’t necessarily become mentally ill, so it’s okay for me to express myself.” [51]

3.2.2. Social Inclusion

“We play games and we just talk about life and then if someone has an idea and then we talk about that.” [51]

3.2.3. Facilitation of Discussions of Difficult Topics

“Home was sad, Kidstime was fun. That’s what I looked forward to. I looked forward to having fun, you know being a child. But at home you have to be an adult, look after yourself, look after mum, look after the house, give her medication; at Kidstime you’re having fun. You’re being looked after and you’re not looking after others…. there are people there who are paying attention to you and you can go and speak to because you probably can’t speak to your mum because you know she’s not well she probably won’t understand. But Kidstime was time for the kids; I think that’s why it’s called Kidstime.” [51]

3.3. Challenges

3.3.1. Hidden Interventions

3.3.2. Practicalities

3.3.3. Age-Appropriate Interventions

“I would like more people my age around.” [51]“The only downside, what I was going to say before but I didn’t want to say anything, was that, I felt more attention was paid to the younger kids than to the 15, 16 year olds.” [51]

3.4. Enablers of Family Recovery Interventions

3.4.1. Written Information

“……even just pointers to that, where you can go on and ask questions because a lot of people have, like I say great knowledge of how to deal with things and it may not be the right ones for you but it it’s ideas isn’t it, to trigger you.” [49]

3.4.2. Access

“I think maybe, that if there had have been a pack when I was going through it…., maybe the outcome for my son would have been different than it is now.” [49]

3.4.3. Support

3.4.4. Decision Makers for Attending Interventions

“I felt shy, I wondered what it was going to do, what it was about. Now I know. It is about having fun and mental illness so when my mum or dad get ill, you can help them.” [51]

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of the Current Literature

4.2. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Review

4.3. Risk of Bias

4.4. Implications for Practitioners and Areas for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Final Reflections

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detailed Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria Based on PICO

| PICO | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Population. |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparison |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

Appendix B. Detailed PICO Explanation for this Systematic Review

| Population | Studies were included if they reported about families with loved ones attending mental health services. These loved ones must have a diagnosis of any mental health condition described within the following diagnostic manuals: International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5). However, exclusions applied in terms of disorders relating to cognitive decline such as dementia or delirium and those specifically relating to intellectual disabilities. These exclusions were applied as such disorders are also mentioned within these diagnostic manuals. |

| Intervention | Papers were included if they discussed recovery interventions that focused on family members in their own right. The definition of recovery interventions that were incorporated into the search strategy related to any intervention (individual or group-based interaction that includes clinician to family member, peer-to-peer, online synchronous, asynchronous, self-help, recovery education, recovery colleges) that increases or decreases the wellbeing of family members or carers of those with a mental health challenge. |

| Comparison | The comparison made for this systematic review was treatment as usual. |

| Outcomes | The outcome which the reviewers seek to capture relates to the efficacy of such interventions for a family member/carer recovery. |

Appendix C. Detailed Search Strategy Family Recovery Interventions: A Systematic Review

Appendix C.1. Search String

Appendix C.2. Database

Appendix C.3. Inclusion/Exclusion

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Qualitative research articles | Quantitative papers, editorials, discussion papers, literature reviews/systematic reviews/meta-synthesis, meta-analysis |

| English Language | |

| Peer reviewed | |

| General adult mental health services | Addiction, Intellectual Disabilities, Physical Health, Older Person Services–Dementia, Delirium, etc, child and adolescent services, dual diagnosis |

| Dissertations | |

| Articles focussed on Family members/carers’ interventions | Article focussed on users of service |

| Articles published within the past 10 years |

Appendix C.4. Systematic Process

References

- Recovery: A Journey for All Disciplines. Available online: https://www.aoti.ie/attachments/3ae57b87-d593-4549-b172-42438ea9c852.PDF (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Slade, M. The contribution of mental health services to recovery. J. Ment. Health 2009, 18, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.J.; Swords, C. Social recovery: A new interpretation to recovery-orientated services—A critical literature review. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2020, 16, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, R.P.; Kopelowicz, A.; Ventura, J.; Gutkind, D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2002, 14, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Guidance Paper on Implementing Organisational and Cultural Change in Mental Health Services in Ireland. Available online: http://www.lenus.ie/hse/bitstream/10147/613321/1/ARIOrganisationalChangeGuidancePaper.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- National Clinical Programmes Mental Health. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/mental-health/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- A Vision for Change: Advancing Mental Health in Ireland Newsletter. Available online: http://recoveryireland.ie/downloads/visionforchangenewsletter9.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Higgins, A.; Hevey, D.; Gibbons, P.; O’Connor, C. A participatory approach to the development of a co-produced and co-delivered information programme for users of services and family members: The EOLAS programme (paper 1). Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2017, 34, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/76770/b142b216-f2ca-48e6-a551-79c208f1a247.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- A Vision for Change: Report of the Expert Group on Mental Health Policy. Available online: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/Mentalhealth/Mental_Health__A_Vision_for_Change.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Quality Framework for Mental Health Services. Available online: http://www.mhcirl.ie/File/qframemhc.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Guidelines for Realising a Family-Friendly Mental Health Service. Available online: https://www.shine.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Guidelines-for-Realising-a-family-friendly-mental-health-service.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- A Vision for Change Nine Years On. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthreform.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/A-Vision-for-Change-web.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Family Caring in Ireland. Available online: http://www.carealliance.ie/userfiles/file/Family%20Caring%20in%20Ireland%20Pdf.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Brazil, K.; Thabane, L.; Foster, G.; Bédard, M. Gender differences among Canadian spousal caregivers at the end of life. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Carers Strategy. Available online: http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/National-Carers-Strategy.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Loukissa, D. Family burden in chronic mental illness: A review of research studies. J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 21, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, E. Family burden and quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12 (Suppl. 1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrowclough, C.; Marshall, M.; Lockwood, A.; Quinn, J.; Sellwood, W. Assessing relatives’ needs for psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: A relatives’ version of the Cardinal Needs Schedule (RCNS). Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faddon, G.; Bebbington, P.; Kuipers, L. Caring and its burdens: A study of the spouses of depressed patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 17, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, A.; Morimoto, T.; Arai, Y.; Zarit, S. Assessing family caregiver’s mental health using a statistically derived cut-off score for the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging Ment. Health 2006, 10, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruvik, F.; Ulstein, I.; Ranhoff, A.; Engedal, K. The quality of life of people with dementia and their family carers. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crellin, N.; Orrell, M.; McDermott, O.; Charlesworth, G. Self-efficacy and health-related quality of life in family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. Families living with severe mental illness: A literature review. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 24, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.; Lucksted, A.; Stewart, B.; Burland, J.; Brown, C.H.; Postrado, L.; McGuire, C.; Hoffman, M. Outcomes of the peer-taught 12-week family-to-family education program for severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 109, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhlbaer, S. Navigating the Storm of Mental Illness: Phases in the family’s journey. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, M.; Barrio, C. Perceptions of subjective burden among Latino families caring for a loved one with Schizophrenia. Community Ment. Health J. 2015, 8, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Act 2014. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- The Carer Recognition Act. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2010A00123 (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- The Social Welfare (Carer’s Allowance) Regulations. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1990/si/242/made/en/print (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- The Carers and Direct Payments Act (Northern Ireland). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/nia/2002/6/contents (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Carers Leave Act. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2001/act/19/enacted/en/html (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- A Recovery Approach within the Irish Mental Health Services: A Framework for Development. Available online: https://www.mhcirl.ie/documents/publications/A%20Framework%20for%20Development%20A%20Recovery%20Approach%20Within%20the%20Irish%20Mental%20Health%20Services%202008.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- The Family Recovery Guidance Document 2018–2020. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/advancingrecoveryireland/national-framework-for-recovery-in-mental-health/family-recovery-guidance-document-2018-to-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- How to Cope When Supporting Someone Else. Available online: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/helping-someone-else/carers-friends-family-coping-support/#.XLiQ46Yo9Bw (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Supporting Family. Available online: https://headtohealth.gov.au/supporting-someone-else/supporting/family (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Dirik, A.; Sandhu, S.; Giacco, D.; Barrett, K.; Bennison, G.; Collinson, S.; Priebe, S. Why involve families in acute mental healthcare? A collaborative conceptual review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Support for Family, Friends and Carers. Available online: https://www.thinkmentalhealthwa.com.au/supporting-others-mental-health/support-for-family-friends-and-carers/ (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Javed, A.; Herrman, H. Involving patients, carers and families: An international perspective on emerging priorities. Br. J. Psychiatry Int. 2017, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, N.; Fernandez, J.; Knapp, M.; Rehill, A.; Wittenberg, R. Review of the international evidence on support for unpaid carers. J. Long-Term Care 2018, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A National Framework for Recovery in Mental Health. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/advancingrecoveryireland/national-framework-for-recovery-in-mental-health/recovery-framework.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E.; Stillwell, S.B.; Williamson, K.M. The seven steps of evidence-based practice. Am. J. Nurs. 2010, 110, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawker, S.; Payne, S.; Kerr, C.; Hardy, M.; Powell, J. Appraising the evidence: Reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenc, T.; Petticrew, M.; Whitehead, M.; Neary, D.; Clayton, S.; Wright, K.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Crime, fear of crime and mental health: Synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Res. 2014, 2, 1–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobban, F.; Glentworth, D.; Haddock, G.; Wainwright, L.; Clancy, A.; Bentley, R.; REACT Team. The views of relatives of young people with psychosis on how to design a Relatives Education and Coping Toolkit (REACT). J. Ment. Health 2011, 20, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagi, C.; Davies, J. Bridging the gap: Brief family psychoeducation in forensic mental health. J. Forensic Psychol. Pract. 2015, 15, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, M.; Hoffman, J.; Martin, A.; Fagin, L.; Cooklin, A. An exploration of the experience of attending the Kidstime programme for children with parents with enduring mental health issues: Parents’ and young people’s views. Clin. Child Psychol. 2015, 20, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatherer, C.; Dickson-Lee, S.; Lowenstein, J. The forgotten families; a systematic literature review of family interventions within forensic mental health services. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2020, 31, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddinott, P.; Pill, R. A review of recently published qualitative research in general practice: More methodological questions than answers? Fam. Pract. 1997, 14, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Qualitative research articles. | Quantitative papers, editorials, discussion papers, literature reviews/systematic reviews/meta-synthesis, meta-analysis. |

| English Language. | |

| Peer-reviewed. | |

| General adult mental health services. | Addiction, Intellectual Disabilities, Physical Health, Older Person Services–Dementia, Delirium, etc, child and adolescent services, dual diagnosis. |

| Dissertations. | |

| Articles focussed on Family members/carers’ interventions. | Article focussed on users of service. |

| Articles published within the past 10 years. |

| Authors/Year/ Geographical Location | Study Aim | Sample and Sample Size | Age Range | Setting | Methodological Approach | Theoretical Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] United Kingdom | To ascertain the views of relatives on how to design a supported self-management intervention for relatives | Relatives–Parents/Partners (n = 23) | 53–63 Years | Non-NHS Community Setting | N/S | N/S |

| [50] 2015 United Kingdom | To describe the development/content/structure of a pilot family psychoeducation programme | Families–Parents/Siblings (n = 10) | N/S | Low Security Forensic Mental Health Services | N/S | N/S |

| [51] 2014 United Kingdom | To present a qualitative analysis of the Kidstime programme | Children/Young People, Former Service Users (n = 15) | 4–16 Years | Non-NHS Community Setting | N/S | N/S |

| Study | Abstract/Title | Introduction/Aims | Data Collection | Sampling | Analysis | Ethics/Bias | Results | Generalisability | Implications | Total | * Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 24 | C |

| [51] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 22 | C |

| [50] | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 20 | C |

| Authors | Synopsis of Included Studies |

|---|---|

| [49] United Kingdom | Family interventions can help to improve outcomes for people with psychosis and their families by reducing hospital admissions and relapse rates. Interventions which reduce stress for families of persons experiencing psychosis should be readily available. This study seeks to elicit the views of families on the content development of a self-management toolkit for families. Qualitative methods were utilised using a sample of adult parents and partners (n = 23). The gender of participants was male (n = 11) and females (n = 12). |

| [50] United Kingdom | There is a dearth of family interventions within forensic mental health settings. This study reports on the development, content, implementation and evaluation of a psychoeducation programme for families with loved ones in forensic mental health settings. Qualitative methods were employed using a sample of adult parents and siblings (n = 10). The gender of participants was not documented in this study. |

| [51] United Kingdom | Children of parents with mental health challenges have a 30–50% chance of becoming seriously mentally unwell themselves. Kidstime is an interactive programme that attempts to address the needs of such children and adolescents. The present study seeks to evaluate Kidstime by exploring service user perspectives. Qualitative methods were used to achieve this using a sample of children, young people and former service users (n = 15). The gender of participants was not documented in this study. |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Family Recovery Initiatives | Recovery Toolkit |

| Family Psychoeducation | |

| Kidstime | |

| Benefits | Education |

| Social Inclusion | |

| Facilitation of Discussion of Difficult Topics | |

| Challenges | Hidden Interventions |

| Practicalities | |

| Age Appropriate Interventions | |

| Enablers for Recovery Interventions | Written Information |

| Access | |

| Supports | |

| Decision Makers for Attending Interventions |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norton, M.J.; Cuskelly, K. Family Recovery Interventions with Families of Mental Health Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157858

Norton MJ, Cuskelly K. Family Recovery Interventions with Families of Mental Health Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(15):7858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157858

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorton, Michael John, and Kerry Cuskelly. 2021. "Family Recovery Interventions with Families of Mental Health Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Literature" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 15: 7858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157858

APA StyleNorton, M. J., & Cuskelly, K. (2021). Family Recovery Interventions with Families of Mental Health Service Users: A Systematic Review of the Literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157858