Does a National Park Enhance the Environment-Friendliness of Tourists as an Ecotourism Destination?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Nature-Based Tourism

2.2. Ecotourism and National Park

2.3. New Ecological Paradigm

2.4. Environmental Conservation and Environment-Friendly Behavioral Intention

3. Methods

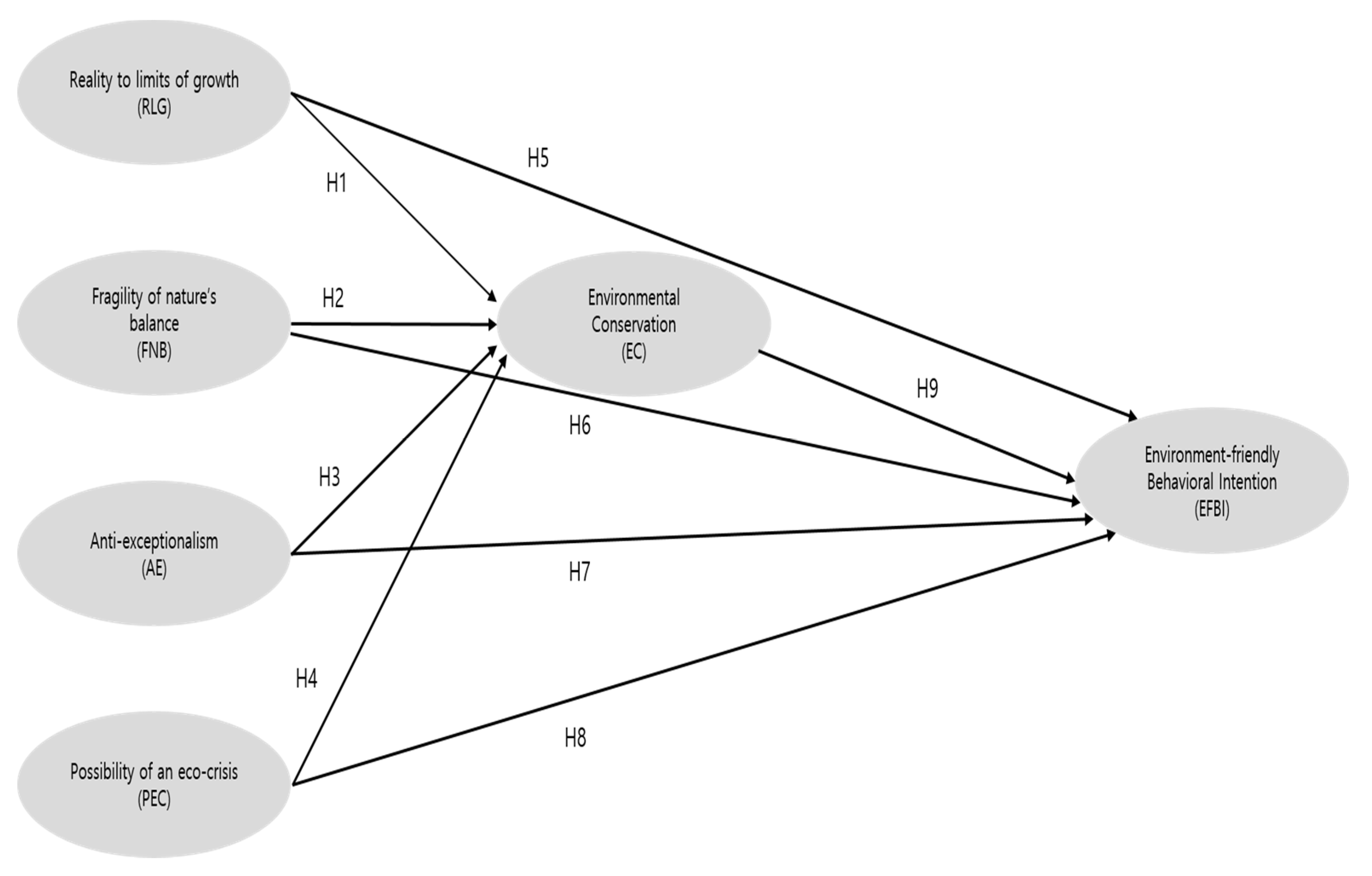

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.2. Study Setting

3.3. The Sample and Data Collection

3.4. Measures and Data Analysis

4. The Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Purification of Scale Items

4.3. Validity and Reliability of Scales through Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Tests

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Arco, M.; Lo Presti, L.; Marino, V.; Maggiore, G. Is sustainable tourism a goal that came true? The Italian experience of the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M.; Hughes, K. Eco-guilt and eco-shame in tourism consumption contexts: Understanding the triggers and responses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1223–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhama, B.; Timang, J.H.; Palangka, J.R.; Raya, K.P. The meta-analysis of Ecotourism in National Parks. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.H.; Moscardo, G. Understanding the impact of ecotourism resort experiences on tourists’ environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo-Cea, J.D.; Velado-Cano, M.A.; Noriega, J.A. A first step to evaluate the impact of ecotourism on biodiversity in El Salvador: A case study using dung beetles in a National Park. J. Ecotourism. 2021, 20, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, F.; Duriez, O.; Dominici, J.M.; Sforzi, A.; Robert, A.; Fusani, L.; Grémillet, D. The price of success: Integrative long-term study reveals ecotourism impacts on a flagship species at a UNESCO site. Anim. Conserv. 2018, 21, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, R.O. Social capital in managing mangrove area as ecotourism by Muara Baimbai Community. Indones. J. For. Res. 2018, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Everhart, W.C.; Dickenson, R.E. The National Park Service; Routledge: New York City, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Korea National Park Service. 2021. Available online: http://www.knps.or.kr/portal (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Chubchuwong, M.; Beise-Zee, R.; Speece, M.W. The effect of nature-based tourism, destination attachment and property ownership on environmental-friendliness of visitors: A study in Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 656–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.C.; Lovrich, N.P., Jr.; Tsurutani, T.; Abe, T. Culture, politics and mass publics: Traditional and modern supporters of the new environmental paradigm in Japan and the United States. J. Politics. 1987, 49, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Guagnano, G.A. The new ecological paradigm in social-psychological context. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.N.; Brehm, H.N. An environmental sociology for the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Oromendía, A.; Reina-Paz, M.D.; Sevilla-Sevilla, C. Environmental awareness of tourists. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 1941–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Confente, I.; Scarpi, D. Achieving environmentally responsible behavior for tourists and residents: A norm activation theory perspective. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Tyrväinen, L. Frontiers in nature-based tourism. Scand. J. Hops. Tour. 2010, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Mota, V.T.; Picjering, C. Using social media to assess nature-based tourism: Current research and future trend. J. Outdo. Recreat. Tour. Res. Plan. 2020, 30, 100295. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Thapa, B. Perceived value and flow experience: Application in a nature-based tourism context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Ecotourism as mass tourism: Contradiction or reality? Cornell Hotel Restaur. Admin. Q. 2001, 42, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M. Nature-based tourism: A contrast to everyday life. J. Ecotourism 2007, 6, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, P.; Wall-Reinius, S.; Grundén, A. The nature of nature in nature-based tourism. Scand. J. Hops. Tour. 2012, 12, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priskin, J. Assessment of natural resources for nature-based tourism: The case of the central coast region of Western Australia. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, B.; Davis, D. An exploratory investigation into the roles of the nature-based tour leader. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Sha, J.; Scott, N. Restoration of visitors through nature-based tourism: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chan, C.S.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H. Different stakeholders’ perceptions and asymmetric influencing factors towards nature-based tourism in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism, and sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duffy, R. Nature-based tourism and neoliberalism: Concealing contradictions. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. Ecotourism behavior of nature-based tourists: An integrative framework. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R. Ecotourism after nature: Anthropocene tourism as a new capitalist “fix”. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, K.; Lee, J. Antecedents and consequences of ecotourism behavior: Independent and interdependent self-construals, ecological belief, willingness to pay for ecotourism services and satisfaction with life. Sustainability 2018, 10, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruhanen, L. The prominence of eco in ecotourism experiences: An analysis of post-purchase online reviews. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Gillen, J.; Friess, D.A. Challenging the principles of ecotourism: Insights from entrepreneurs on environmental and economic sustainability in Langkawi, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.H. Economic impact of wetland ecotourism: An empirical study of Taiwan’s Cigu Lagoon area. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.H.; Nepal, S.K. Local perspectives of ecotourism development in Tawushan Nature Reserve, Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Paydar, M.M. Discount and advertisement in ecotourism supply chain. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T.B.; Gribb, W.J. Sustainable ecotourism management and visitor experiences: Managing conflicting perspectives in Rocky Mountain National Park, USA. J. Ecotourism 2018, 17, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G. Relationships, networks and the learning regions: Case evidence from the Peak District National Park. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Hong, C.F.; Lee, C.H.; Chou, Y.A. Integrating multiple perspectives into an ecotourism marketing strategy in a Marine National Park. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 25, 948–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, C.; Cheng, K.; Lee, C.H.; Hsu, N.L. Capturing tourists’ preferences for the management of community-based ecotourism in a forest park. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eshetu, A.A. Development of community based ecotourism in Borena-Saynt National Park, North central Ethiopia: Opportunities and challenges. J. Hosp. Manage. Tour. 2014, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, F.J.; Naiman, R.J.; Biggs, H.C.; Pienaar, D.J. The evolution of conservation management philosophy: Science, environmental change and social adjustments in Kruger National Park. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, N.; Garling, T. Environmental concern: Conceptual definitions, measurement methods, and research findings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1999, 19, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olli, E.; Grendstad, G.; Wolleback, D. Correlates of environmental behaviors: Bringing back social context. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawcroft, L.J.; Milfont, T.L. The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.; Poe, G.L.; Bateman, I.J. The structure of motivation for contingent values: A case study of lake water quality improvement. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 50, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.; Skordoulis, M.; Chalikias, M.; Arabatzis, G. An application of the new environmental paradigm (NEP) scale in a Greek context. Energies 2019, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J. The New Environmental Paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Brauchle, G.; Haq, A.; Stecker, R.; Wong, K.; Shapiro, E. Young children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.A. Environmental perspectives of Blacks: Acceptance of the ‘new environmental paradigm’. J. Environ. Educ. 1989, 20, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraway, J.; Broughton-Ansin, F.; Deaker, L.; Jowett, T.; Shephard, K. Exploring the use of the revised new ecological paradigm scale (NEP) to monitor the development of students’ ecological worldviews. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 43, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, S.; Alam, K.; Beaumont, N. Environmental orientations and environmental behaviour: Perceptions of protected area tourism stakeholders. Tour. Manage. 2014, 40, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, H.D.; Pereira, L.N. Measuring the level of endorsement of the New Environmental Paradigm: A transnational study. DAMeJ 2017, 23, 4–26. [Google Scholar]

- La Trobe, H.L.; Acott, T.G. Modified NEP/DSP Environmental Attitudes Scale. J. Environ. Edu. 2000, 32, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, N. Testing the new ecological paradigm scale: Turkish case. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 4, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Manoli, C.C.; Johnson, B.; Buxner, S.; Bogner, F. Measuring environmental perceptions grounded on different theoretical models: The 2-Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) model in comparison with the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manoli, C.C.; Johnson, B.; Dunlap, R.E. Assessing children’s environmental worldviews: Modifying and validating the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for use with children. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Pascual, U.; Stenseke, M.; Martín-López, B.; Watson, R.T.; Molnár, Z.; Shirayama, Y. Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 2018, 359, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghoddousi, S.; Pintassilgo, P.; Mendes, J.; Ghoddousi, A.; Sequeira, B. Tourism and nature conservation: A case study in Golestan National Park, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Hansen, A.; Newton, A.C.; Hansen, M.C. Increasing isolation of protected areas in tropical forests over the past twenty years. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalani, J.O. Local people’s perception on the impacts and importance of ecotourism in Sabang, Palawan, Philippines. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karp, D.G. Values and their effect on pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Long, P. Environment-friendly tourists: What do we really know about them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, Y.J.; Park, O.L.; Ha, J.K. The effect of the clothing benefits sought on the environmental awareness and environment-friendly consuming behavior. J. Kor. Soc. Cloth. Ind. 2006, 8, 639–646. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, D.; Cools, M.; Moons, E.; Wets, G.; Arentze, T.A.; Timmermans, H.J. Road pricing as am impetus for environment-friendly travel behavior: Results from a stated adaption experiment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2115, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdowski, L.A.; Grahn, A.H.; Hansen, H.; Skeiseid, H. The new ecological paradigm, pro-environmental behavior, and the moderating effects of locus of control and self-construal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, M.; Warriner, G.K.; Farmer, J.R.; Larson, B.M. Private landowners and environmental conservation: A case study of socialpsychological determinants of conservation program participation in Ontario. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Bechtel, R.B.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Environmental beliefs and water conservation: An empirical study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.A.; Scherer, R.F. An analysis of the predictive validity of the new ecological paradigm scale. J. Environ. Edu. 2003, 34, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaura, A. Using the theory of planned behavior to investigate the determinants of environmental behavior among youth. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2013, 63, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 2012, 31, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-environmental behavior from a socialcognitive theory perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korea National Park Service. National Park Basic Statistics. 2021. Available online: http://www.knps.or.kr/front/portal/stats (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Norman, K.L.; Friedman, Z.; Norman, K.; Stevenson, R. Navigational issues in the design of online self-administrated questionnaires. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2001, 20, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Redline, C.D. Testing paper self-administrated questionnaires: Cognitive interview and field test comparisons. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; Presser, S., Rothgeb, J.M., Couper, M.P., Lessler, J.T., Martin, E., Martin, J., Singer, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, G.M. Validity evidence against the children’s new ecological paradigm scale. J. Environ. Edu. 2020, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, N.; Stern, M.J.; Hammett, A.L. Developing a scale for evaluating ecotourism by visitors: A study in the Annapurna conservation area, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Lewis, G.J. Unearthing the “green” personality: Core traits predict environmentally friendly behavior. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Gordon, S.; Mallett, C.J.; Temby, P. The concept of mental toughness: Tests of dimensionality, nomological network, and traitness. J. Pers. 2015, 83, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, E.; Shim, C.; Brown, A.D.; Lee, S. Development of a scale to measure intrapersonal psychological empowerment to participate in local tourism development: Applying the sociopolitical control scale construct to tourism (SPCS-T). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.A. Technology success and failure in winter-take-all markets: The impact of learning orientation, timing, and network externalities. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- Throndike, R.M.; Throndike-Christ, T. Measurement and Evaluation in Psychology and Education; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.T.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Li, B. Millennial tourists’ environmentally sustainable behavior towards a natural protected area: An integrative framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| NEP | Reality to limits of growth (RLG) | Humans are approaching the limits of the capacity of people the Earth can support (RLG1). The Earth provides plenty of natural resources for humans if we learn how to develop and protect them (RLG2). The Earth is like a ship with very limited natural resources (RLG3). |

| Fragility of nature’s balance (FNB) | When humans abuse nature, it often produces disastrous consequence (FNB1). | |

| The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of powerful nations (FNB2). The balance of nature is delicate and easily destroyed (FNB3). | ||

| Anti-exceptionalism (AE) | The present human development of natural resources will ensure that we do not make the Earth unlivable (AE1). Despite humans’ special abilities, we are still subject to the laws of nature (AE2). Humans will ultimately be sufficiently knowledgeable about how nature works to be able to control it (AE3). | |

| Possibility of an eco-crisis (PEC) | Humans are heavily abusing the environment (PEC1). The ecological crisis facing humankind has been greatly progressed (PEC2).If humans continue with their present environmental abuse, we will experience a major ecological catastrophe (PEC3). | |

| Environmental Conservation (EC) | I am willing to accommodate closing trails in the national park (EC1). I am able to help maintain the quality of the national park (EC2). I am willing to donate to protecting the national park (EC3). I can inform other of the significance of national park as an environment-friendly tourism destination (EC4). | |

| Environment-friendly Behavioral Intention (EFBI) | I am willing to revisit this national park as an ecotourism destination (EFBI1). I am willing to recommend this national park as an ecotourism destination to others (EFBI2). I am willing to introduce this national park as an ecotourism destination to others (EFBI3). I am willing to visit other national park (EFBI4). | |

| Dimension | Items | Factor Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLG | RLG2 | 0.823 | 3.499 | 17.493 | 0.950 |

| RLG1 | 0.796 | ||||

| RLG3 | 0.654 | ||||

| FNB | FNB1 | 0.753 | 3.429 | 17.145 | 0.920 |

| FNB2 | 0.730 | ||||

| FNB3 | 0.692 | ||||

| AE | AE1 | 0.812 | 2.560 | 12.799 | 0.805 |

| AE2 | 0.773 | ||||

| AE3 | 0.583 | ||||

| PEC | PEC1 | 0.792 | 2.414 | 12.070 | 0.870 |

| PEC2 | 0.757 | ||||

| PEC3 | 0.692 | ||||

| EC | EC1 | 0.829 | 2.227 | 11.135 | 0.935 |

| EC2 | 0.820 | ||||

| EC3 | 0.811 | ||||

| EC4 | 0.804 | ||||

| EFBI | EFBI1 | 0.903 | 2.161 | 10.804 | 0.932 |

| EFBI2 | 0.882 | ||||

| EFBI3 | 0.858 | ||||

| EFBI4 | 0.855 | ||||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = 0.932, Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ2 = 15,989.269, df(p) = 190(0.000).Total variance explained by 6 factors: 81.446%. | |||||

| Dimension | Items | Standardization Coefficient | Variance of the Error | AVE | C.R. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLG | RLG1 | 0.891 | 0.145 | 0.761 | 0.904 |

| RLG2 | 0.879 | 0.158 | |||

| RLG3 | 0.668 | 0.330 | |||

| FNB | FNB1 | 0.844 | 0.218 | 0.847 | 0.943 |

| FNB2 | 0.922 | 0.102 | |||

| FNB3 | 0.911 | 0.112 | |||

| AE | AE1 | 0.752 | 0.353 | 0.644 | 0.844 |

| AE2 | 0.716 | 0.370 | |||

| AE3 | 0.806 | 0.233 | |||

| PEC | PEC1 | 0.817 | 0.229 | 0.769 | 0.908 |

| PEC2 | 0.892 | 0.124 | |||

| PEC3 | 0.768 | 0.265 | |||

| EC | EC1 | 0.922 | 0.116 | 0.826 | 0.950 |

| EC2 | 0.919 | 0.119 | |||

| EC3 | 0.880 | 0.160 | |||

| EC4 | 0.812 | 0.262 | |||

| EFBI | EFBI1 | 0.876 | 0.156 | 0.845 | 0.956 |

| EFBI2 | 0.915 | 0.106 | |||

| EFBI3 | 0.879 | 0.149 | |||

| EFBI4 | 0.877 | 0.164 | |||

| χ2/df = 2.587, TLI = 0.981, NFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.987, GFI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.041. | |||||

| Factors | RLG | FNB | AE | PEC | EC | EFBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLG | 0.761 | |||||

| FNB | 0.711 ** | 0.847 | ||||

| (0.506) | ||||||

| AE | 0.714 ** | 0.749 ** | 0.644 | |||

| (0.509) | (0.561) | |||||

| PEC | 0.746 ** | 0.806 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.769 | ||

| (0.557) | (0.650) | (0.471) | ||||

| EC | 0.586 ** | 0.694 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.659 ** | 0.826 | |

| (0.343) | (0.482) | (0.376) | (0.434) | |||

| EFBI | 0.362 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.407 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.479 ** | 0.845 |

| (0.131) | (0.208) | (0.166) | (0.179) | (0.229) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, E.; Lee, T.; Brown, A.D.; Choi, S.; Son, M. Does a National Park Enhance the Environment-Friendliness of Tourists as an Ecotourism Destination? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168321

Jeong E, Lee T, Brown AD, Choi S, Son M. Does a National Park Enhance the Environment-Friendliness of Tourists as an Ecotourism Destination? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168321

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Eunseong, Taesoo Lee, Alan Dixon Brown, Sara Choi, and Minyoung Son. 2021. "Does a National Park Enhance the Environment-Friendliness of Tourists as an Ecotourism Destination?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168321

APA StyleJeong, E., Lee, T., Brown, A. D., Choi, S., & Son, M. (2021). Does a National Park Enhance the Environment-Friendliness of Tourists as an Ecotourism Destination? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8321. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168321