The Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Tunisia, France, and Germany: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Different National Strategies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Its contagion and its high rate of spread caused the saturation of all health systems, even the most resilient. By 2 November 2020 the world had seen 46,049,978 cases and 1,201,442 deaths, including 516,774 new cases of contamination and 6088 new deaths in the previous 24 h [5].

- Its severity (20% of infected people develop a serious or critical form of the disease [4]).

- Its profound societal and economic consequences (over USD 220 billion has been lost in developing countries [6]).

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Socio-Economic Situations of Tunisia, Germany, and France

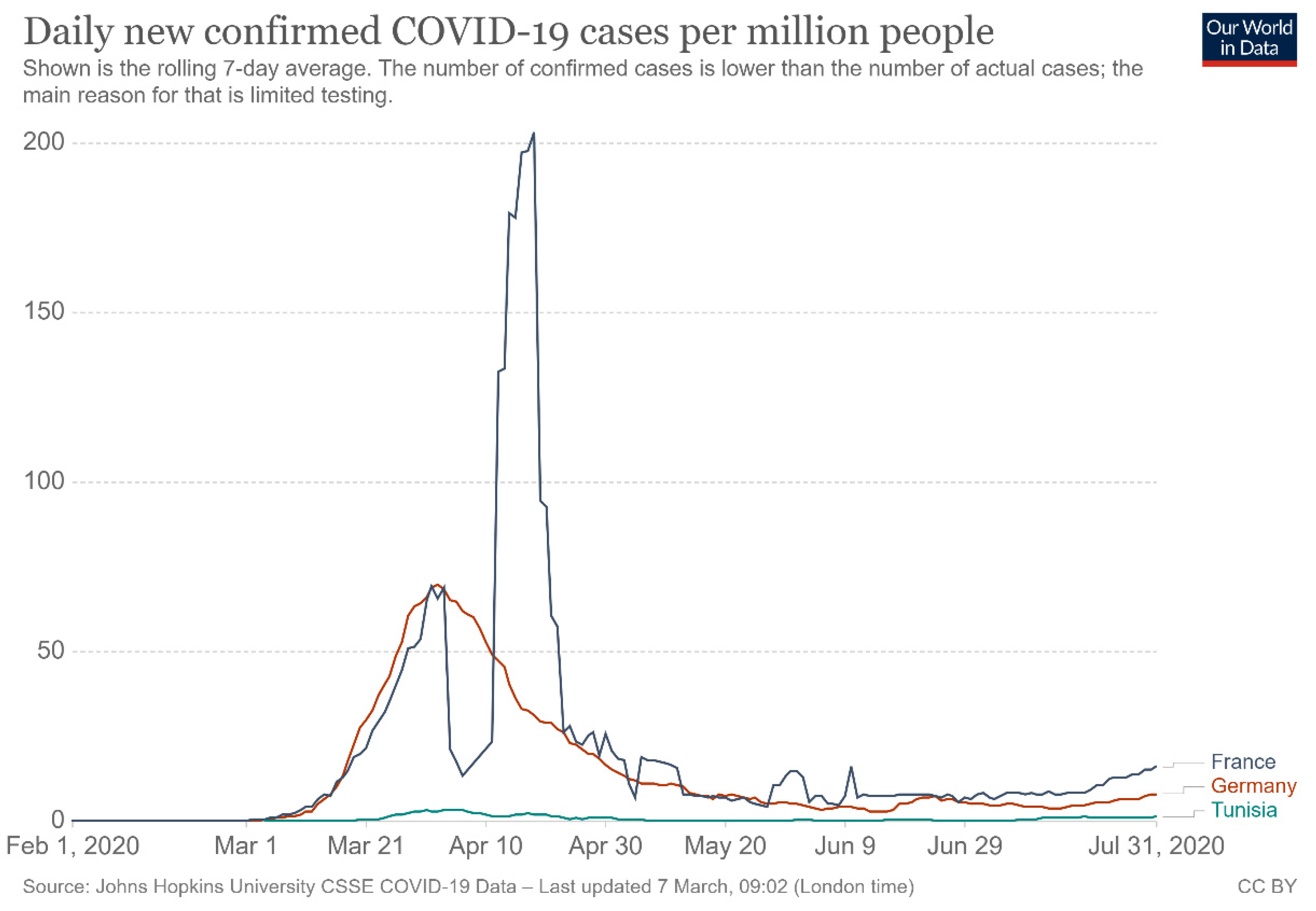

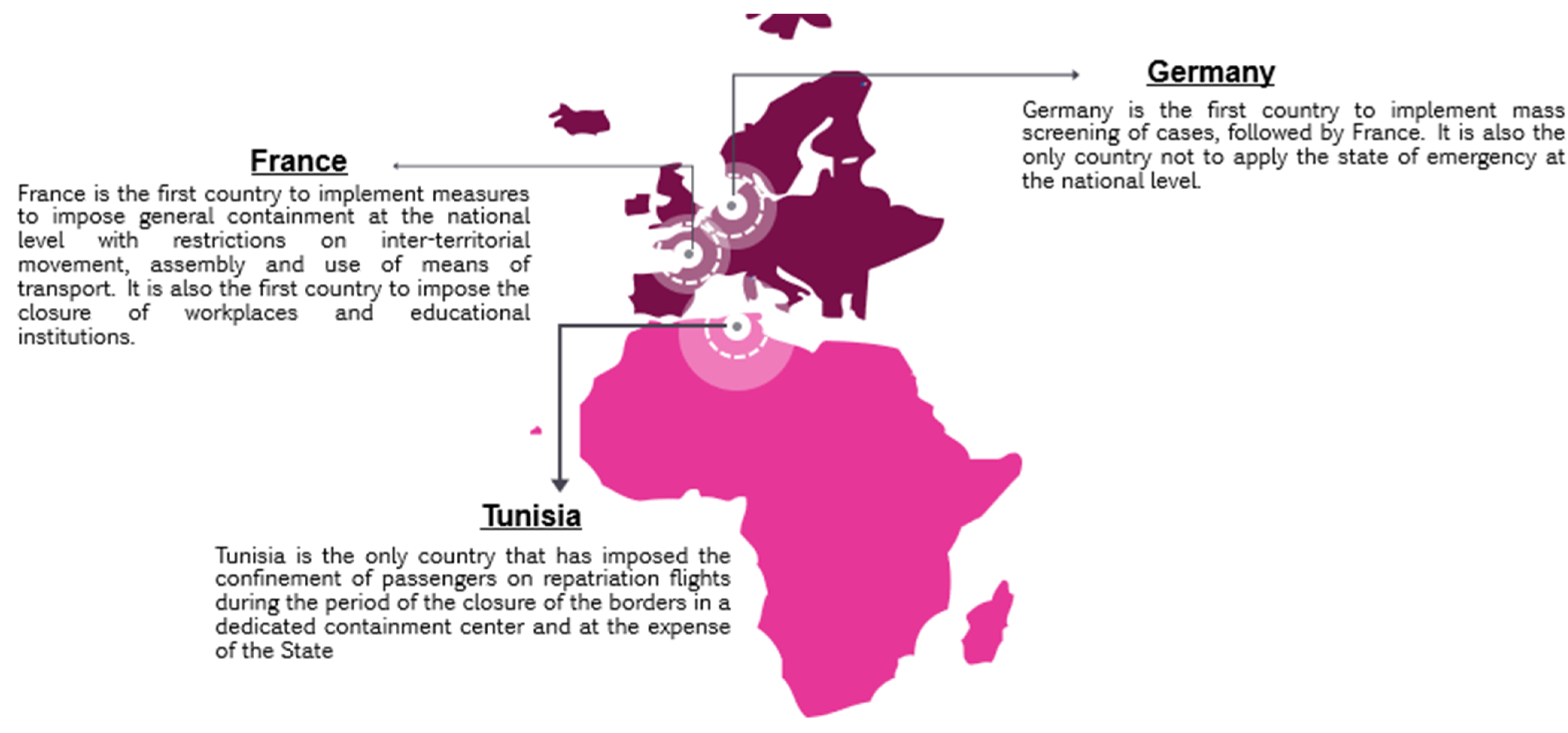

1.1.2. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Tunisia, Germany, and France

1.1.3. The World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Strategic Plan and Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

- 1.

- National coordination, planning, and surveillance: Successful implementation of adaptive COVID-preparedness and response strategies will depend on the participation of the whole society in the plan and on the strength of national and sub-national coordination.

- 2.

- Risk communication and public engagement: Transparent communication to the public with responsive, empathetic, and culturally appropriate messages. Implementation of systems to detect and respond to concerns, rumors and false information.

- 3.

- Surveillance, early intervention, and case investigation: Early detection of imported cases, comprehensive and rapid contact tracing, and case investigation.

- 4.

- Ports of entry: Support for efforts and resources at ports of entry.

- 5.

- National laboratories: Preparation of laboratory capacity to manage the volume of COVID-19 testing.

- 6.

- Infection, prevention, and control: Review and improvement of infection prevention and control practices.

- 7.

- Case management: Preparation of health facilities and training of health professionals for the management of COVID-19 cases.

- 8.

- Logistics and operational support: Identification of resources and supply systems (supply, storage, security, transportation, and distribution).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- P (population): the governments of the three countries concerned (France, Germany, Tunisia)

- I (intervention): COVID-19 national pandemic strategies and policies

- S (study design): Any document that meets the following criteria will be included:

- o

- Any scientific article or official institutional document.

- o

- Carried out before 31 July 2020.

- o

- Languages: studies written in French, Arabic, German, or English.

- o

- Concerns France, Germany, or Tunisia.

2.3. Information Sources

- The electronic database PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Google Scholar for the search of grey literature.

- The platform of the French Ministry of Solidarity and Health (https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The platform Santé Publique France”’ (https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The French government website (https://www.gouvernement.fr/, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The platform of the Robert Koch Institute (Germany) (https://www.rki.de/DE/Home/homepage_node.html, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The platform of the Federal Ministry of Health Germany (https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The platform of the Ministry of Public Health Tunisia (http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The National Observatory for New and Emerging Diseases (https://www.onmne.tn/fr/index.php, accessed on 1 September 2020).

- The website “COVID-19 Tunisia”, which was set up by the Presidency of the Tunisian government (https://covid-19.tn/fr/accueil-2, accessed on 2 September 2020).

2.4. Search Strategy

- 1#: “2019 nCoV” OR “2019nCoV” OR “2019 novel coronavirus” OR “COVID-19” OR COVID19 OR “new coronavirus” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “SARS CoV-2” OR “فيروس كورونا المستجد’’.

- 2#: “Tunisia” OR “France” OR “Germany” OR “Deutschland” OR “Tunisie” OR “Tunesien” OR “Frankreich” OR “Allemagne” OR “تونس” OR “ فرنسا” OR”ألمانيا “

- 3#: “Health Polic”[Mesh]” OR “Strategy” OR “ Strategie”; OR “ إستراتيجية “ OR “ Gesundheitspolitik”

- Equation de recherche (Pubmed): 1# AND 2# AND 3#

- Keywords used to search for institutional documents:

- For Tunisian websites: 2019 novel coronavirus/COVID-19/new coronavirus/novel coronavirus/SARS CoV-2/les coronavirus/la pandémie de covid-19/فيروس كورونا المستجد/كورونافيروس/وباء الكورونا

- For French websites: 2019 novel coronavirus/COVID-19/new coronavirus/novel coronavirus/SARS CoV-2/les coronavirus/la pandémie de covid-19/

- For German websites: 2019 novel coronavirus/COVID-19/new coronavirus/novel coronavirus/SARS CoV-2/Coronaviren/die Covid-19 Pandemie/

2.5. Study Records

- Identification by title: in a first step, the documents were identified according to their titles.

- Eligibility: the second identification was carried out on the summary of each bibliographic reference (this step concerned only scientific articles).

- Inclusion: based on the complete texts, by applying the pre-established criteria and after elimination of duplicates.

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Pillar 1: National Coordination, Planning, and Monitoring

3.2.2. Pillar 2: Risk Communication and Population Mobilization

3.2.3. Pillar 3: Surveillance, Rapid Response Teams, and Case Investigation

3.2.4. Pillar 4: Points of Entry, International Travel, and Transport

3.2.5. Pillar 5: National Laboratories

3.2.6. Pillar 6: Infection Prevention and Control

3.2.7. Pillar 7: Case Management

3.2.8. Pillar 8: Maintaining Essential Health Services and Systems

3.3. Synthesis of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Method

4.2. Discussion of Results

4.2.1. Impact of the Political Regime

4.2.2. Testing/Screening Strategy and Tracing

4.2.3. Importance of Prevention and Predictive Measures

4.2.4. Social Acceptance and Commitment

4.2.5. Continuity of Non-COVID-19 Care Services

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. WHO Official Website. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Eastin, C.; Eastin, T. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China: Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y; et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Feb 28 [Online ahead of print] doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 58, 711–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Goel, A.D.; Gupta, N. Emerging prophylaxis strategies against COVID-19. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2020, 90, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- mondiale de la Santé, O.; World Health Organization. COVID-19 strategy update (as of 14 April 2020)—Mise à jour de la stratégie COVID-19 (au 14 avril 2020). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. Relev. Épidémiologique Hebd. 2020, 95, 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rapport de L’organisation Mondiale de la Santé du 1er Juillet. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200701-covid-19-sitrep-163.pdf?sfvrsn=c202f05b_2 (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Programme des Nations Unles pour le Développement. COVID-19, Réponse Intégrée du PNUD. Available online: https://www1.undp.org/content/undp/fr/home/librarypage/hiv-aids/covid-19-undp_s-integrated-response.html (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Contreras, G.W. Getting ready for the next pandemic COVID-19: Why we need to be more prepared and less scared. J. Emerg. Manag. 2020, 18, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.E.L.; Leo, Y.S.; Tan, C.C. COVID-19 in Singapore-current experience: Critical global issues that require attention and action. JAMA 2020, 323, 1243–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, J.; Shah, S.U.; Chua PE, Y.; Gui, H.; Pang, J. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Cases During the Early Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Afrique SAS. Une Entité du Réseau Deloitte. COVID-19: Gouverner l’imprévisible—Analyse Comparative des Différentes Stratégies de Crise Déployées. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/fr/Documents/covid-insights/gouverner_imprevisible.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Hale, T.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S. Variation in government responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik Sch. Gov. Work. Paper 2020, 31, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Country Health Profiles. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Website of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/country-health-profiles-eu.htm (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Stafford, N. Covid-19: Why Germany’s case fatality rate seems so low. BMJ 2020, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santé Publique France. COVID-19: Point Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire du 30 Avril 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/documents/bulletin-national/covid-19-point-epidemiologique-du-30-avril-2020 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response (SPRP). Monitoring and Evaluation Framework. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/monitoring-and-evaluation-framework (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- James, K.L.; Randall, N.P.; Haddaway, N.R. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environ. Evid. 2016, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmucker, C.; Motschall, E.; Meerpohl, J. Methoden des Evidence Mappings: Eine Systematische Übersicht; Deutsches Cochrane Deutschland: Freiburg, Deutschland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.L.A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)-Situation Report-10–30 January 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200130-sitrep-10-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=d0b2e480_2 (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Binder, K.; Diaz Crego, M.; Eckert, G.; Kotanidis, S.; Manko, R.; Del Monte, M. States of emergency in response to the coronavirus crisis: Situation in certain Member States. EPRS Eur. Parliam. 2020, 659, 408. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, T.; Webster, S.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Kira, B. COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Blavatnik Sch. Gov. 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Hasell, J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World Data. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/democratic-republic-of-congo?country=~COD (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Barro, K.; Malone, A.; Mokede, A.; Chevance, C. Management of the COVID-19 epidemic by public health establishments—Analysis by the Federation hospitaliere de France. J. Chir. Visc 2020, 157, S20–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrer, A.; Frese, T.; Karch, A.; Mau, W.; Meyer, G.; Richter, M.; Schildmann, J.; Steckelberg, A.; Wagner, K.; Mikolajczyk, R. COVID-19: Knowledge, risk perception and strategies for handling the pandemic. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes 2020, 153–154, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Décret no 2016-1327 du 6 Octobre 2016 Relatif à L’organisation de la Réponse du Système de Santé (Dispositif « ORSAN ») et au Réseau National des Cellules D’urgence Médico-Psychologique pour la Gestion des Situations Sanitaires Exceptionnelle. Journal Officiel de la République Française. 2016. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000033203698 (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Décret n° 2005-3294 du 19 Décembre 2005, Portant Création de L’observatoire National des Maladies Nouvelles et Émergentes et Fixant son Organisation Administrative et Financière ainsi que les Modalités de son Fonctionnement. PUBLIQUE, M.D.L.S., Ed. Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne. 2005. Available online: http://www.legislation.tn/sites/default/files/fraction-journal-officiel/2005/2005F/102/TF200532943.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Décret no 2020-524 du 5 mai 2020 Modifiant le Décret no 2016-151 du 11 Février 2016 Relatif aux Conditions et Modalités de mise en Œuvre du Télétravail Dans la Fonction Publique et la Magistrature. FRANÇAISE, J.O.D.L.R., Ed. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000041849917 (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- 4.1 Décret du 8 Janvier 1953, Relatif aux Règlements de la Police Sanitaire. République Tunisienne Titre Vi: La Prevention, Soins Et MedicamentsSanté; M.d.l., Ed.; 1953. Tunisia health ministry official website November 2020. Available online: http://www.santetunisie.rns.tn/fr/images/textejuridique/decret1953.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Robert Koch Institut Website. Mission Statement. Available online: https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Institute/Mission_Statement/Mission_Statement_node.html (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Official Website of the Covidnet project. Available online: https://covidnet.fr/fr/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Web Page E7mi App. Available online: https://app.e7mi.tn/language (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- L’application StopCovid est Disponible au Téléchargement Dans les Magasins D’applications. Available online: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/appli-stop-covid-disponible (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Corona Warn APP Website. Available online: https://www.coronawarn.app/de/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Tableau de Bord COVID 19 Tunisie. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/fr/tableau-de-bord/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Carte et Données COVID 19 France. Available online: https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/carte-et-donnees (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- COVID-19-Dashboard mit Täglich Aktualisierten Fallzahlen. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/478220a4c454480e823b17327b2bf1d4 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Robert Koch Institut. Ergänzung zum Nationalen Pandemieplan—COVID-19—Neuartige Coronaviruserkrankung. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Ergaenzung_Pandemieplan_Covid.html (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- o.n.d.m.é. (Ed.) Plan de Préparation et de Riposte au Risque D’introduction et de Dissémination du « SARS-CoV-2 » en Tunisie. Tunisie; Observatoire National des Maladies Émergentes Tunisie: Tunis, Tunisia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Koch Institut. Strukturen und Massnahmen—Nationaler Pandemieplan Teil I. 2017. Available online: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/187 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- la Fiche Pratique: Présentation du CORRUSS. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/fiche-corruss_14jan19.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- REGLEMENT INTERIEUR DU CONSEIL SCIENTIFIQUE COVID-19. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2020. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/reglement_interieur_cs.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Avis n°6 du Conseil scientifique COVID-19 20 avril 2020 SORTIE PROGRESSIVE DE CONFINEMENT PREREQUIS ET MESURES PHARES; Santé Publique France Official Website. 2020. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/avis_conseil_scientifique_20_avril_2020.pdf. (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): Questions Relating to Labour Law and Safety and Health at Work. Available online: https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Arbeitsschutz/corona-faqs-en.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Personnes Vulnérables: Le Nouveau Dispositif Mis en Place Depuis le 31 Août. Site Officiel de L’administration Française. 2020. Available online: https://pays-de-la-loire.dreets.gouv.fr/Personnes-vulnerables-le-nouveau-dispositif-a-partir-du-31-aout (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- RKI Website -Gesundheitsmonitoring. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/gesundheitsmonitoring_node.html;jsessionid=BE9121AFA89FD6F744A370F3BB1CA847.internet081 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- اسألعزيزة. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a7%d8%b3%d8%a3%d9%84-%d8%b9%d8%b2%d9%8a%d8%b2%d8%a9/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Dispositifs D’aide à Distance en Santé Accessibles Pendant L’épidémie de Covid-19. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/a-propos/services/aide-a-distance-en-sante-l-offre-de-service (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- PRÉPARATION AU RISQUE ÉPIDÉMIQUE Covid-19. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé FRANCE: 2020. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/guide_methodologique_covid-19-2.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Robert Koch institut. Bericht zur Optimierung der Laborkapazitäten zum Direkten und Indirekten Nachweis von SARS-CoV-2 im Rahmen der Steuerung von Maßnahmen. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Laborkapazitaeten.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Guide Parcours du Patient Suspect ou Atteint par le Covid-19 Situations Particulières 08 Avril 2020. Direction Qualité des Soins et Sécurité des Patients. 2020. Available online: http://ineas.tn/sites/default/files/parcours_du_patient_atteint_du_covid-19.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Optionen zur Getrennten Versorgung von COVID-19-Fällen, Verdachtsfällen und Anderen Patienten im Stationären Bereich. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Getrennte_Patientenversorg_stationaer.html (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Plan Organisationnel D’un Etablissement De Santé COVID-19. Direction de l’Accréditation en Santé. Available online: https://www.ineas.tn/sites/default/files/plan_organisationnel_dun_es_covid-_avril_2020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Fiche Professionnels De Santé Prise En Charge Par Les Médecins De Ville Des Patients Atteints De Covid-19 En Phase De Déconfinement. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé Site de Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé 2020. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/prise-en-charge-medecine-ville-covid-19.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Plan Blanc et Gestion de Crise, Guide D’aide à L’élaboration des Plans Blancs Élargis et des Plans Blancs des Établissement de Santé. Ministère de la Santé et des Solidarités 2006. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/systeme-de-sante-et-medico-social/securite-sanitaire/article/la-gestion-de-crise-des-etablissements-de-sante (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Hinweise zum Ambulanten Management von COVID-19-Verdachtsfällen und Leicht Erkrankten Bestätigten COVID-19-Patienten. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/ambulant.html?nn=13490888 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Covid-19 Dispositif D’accompagnement Personnalisé des Personnes Contacts. Direction Générale de la Santé 2020. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/media/files/01-maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/dispositif-d-accompagnement-personnalise-des-personnes-contacts (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Conduite à Tenir Devant un Patient Suspect D’infection au SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Site de Santé publique France. 2020. Available online: https://splf.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SPF-Conduite-a-tenir-devant-un-patient-suspect-infection-au-SARS-CoV-2-COVID-19-03-04-20.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Adaptation du Plan de Riposte « 2P2R COVID-19 » pendant la phase d’ouverture des Frontières. République Tunisienne Ministére de la Santé. Available online: https://www.onmne.tn/?p=10216 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Santé Publique France. COVID-19: Une Étude Pour Connaître la part de la Population Infectée par le Coronavirus en France. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/covid-19-etudes-pour-suivre-la-part-de-la-population-infectee-par-le-sars-cov-2-en-france (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- L’établissement de Santé en Tension. Available online: https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Guide_de_l_etablissement_de_sante_en_tension.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Besprechung der Bundeskanzlerin mit den Regierungschefinnen und Regierungschefs der Länder am 22. März 2020. The German Federal Government Official Website. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/besprechung-der-bundeskanzlerin-mit-den-regierungschefinnen-und-regierungschefs-der-laender-vom-22-03-2020-1733248 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- COVID-19—Situation des Français Bloqués à L’étranger—Entretien de M. Jean-Yves Le Drian, Ministre de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères, Avec France Info (Paris, 20/03/2020). Available online: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/covid-19_-_situation_des_francais_bloques_a_l_etranger_-_entretien_de_m._jean-yves_le_drian_ministre_de_l_europe_et_des_affaires_etrangeres_avec_france_info_paris_20032020__cle0177a9.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Spahn, B.J.; Spahn: “Schritt um Schritt Wieder zu Einer Normaleren Versorgung in den Kliniken Kommen”. WAZ-Interview, Ed. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit DEUTSCHLAND WEBSITE. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/presse/interviews/interviews/waz-260420.html (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Kabinett Beschließt Entwurf Eines Zweiten Gesetzes zum Schutz der Bevölkerung bei Einer Epidemischen Lage von Nationaler Tragweite. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/covid-19-bevoelkerungsschutz-2.html (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- ندوةصحفيةلوزارتيالصحةوالداخلية Portail Covid19 Tunisie, République Tunisienne, Présidence du Gouvernement, Ministère de la Santé. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/%20%20%D9%86%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%A9%20%D8%B5%D8%AD%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%A9%20%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B2%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AA%D9%8A%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B5%D8%AD%D8%A9%20%D9%88%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AE%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Robert Koch Institut. COVID-19: Jetzt handeln, vorausschauend planen Strategie-Ergänzung zu empfohlenen Infektionsschutzmaßnahmen und Zielen (2. Update). Epidemiol. Bull. 2020, 12, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch Institut. Vorläufige Bewertung der Krankheitsschwere von COVID-19 in Deutschland basierend auf übermittelten Fällen gemäß Infektionsschutzgesetz. Epid. Bull. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point de Situation sur L’épidémie D’infections au Nouveau Coronavirus « 2019-nCov » A la Date du 26 Janvier 2020, 11H30. Santé, M.d.l., Ed. République Tunisienne Site Web de L’observatoire National des Maladies Nouvelles et Émergentes 2020. Available online: http://wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Point_situation_epidemie_infections_Nouveau_Coronavirus_2019-nCoV_-26012020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- الإجراءاتالمتخذةإلىحدوديوم 9 مارس 2020. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a5%d8%ac%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%a1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%b9%d8%aa%d9%85%d8%af%d8%a9-%d8%a5%d9%84%d9%89-%d8%ad%d8%af%d9%88%d8%af-%d9%8a%d9%88%d9%85-09-%d9%85%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%b3/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Gouvernement Liberté Egalité Fraternité. Info Coronavirus/les Actions du Gouvernement. Available online: https://www.gouvernement.fr/info-coronavirus/les-actions-du-gouvernement (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- COVID-19: Notre Action. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/dossiers/coronavirus-covid-19/covid-19-notre-action (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Santé Publique France. COVID-19—Etat des Connaissances et Veille Documentaire. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/dossiers/coronavirus-covid-19/covid-19-etat-des-connaissances-et-veille-documentaire (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- توقيتواجراءاتاستئنافالعملفيالمؤسّساتالعموميّةوالهيئاتوالمؤسّساتوالمنشآتالعموميّةمن 04 مايالى 24 ماي. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%aa%d9%88%d9%82%d9%8a%d8%aa-%d9%88%d8%a7%d8%ac%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%a1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a7%d8%b3%d8%aa%d8%a6%d9%86%d8%a7%d9%81-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%85%d9%84-%d9%81%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%a4%d8%b3/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; , Présidence du Gouvernement, Ministère de la Santé. قراراتمجلسالأمنالقوميلمنعتفشيفيروسكورونا. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d9%82%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%85%d8%ac%d9%84%d8%b3-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a3%d9%85%d9%86-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%82%d9%88%d9%85%d9%8a-%d9%84%d9%85%d9%86%d8%b9-%d8%aa%d9%81%d8%b4%d9%8a-%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%b1/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T. Présidence du Gouvernement, Ministère de la Santé بلاغحولتعليقالعملالحضوريبمصالحالدولةوالجماعاتالمحليةوالمؤسساتالعموميةذاتالصبغةالإداريةوالمؤسساتوالمنشآتالعمومية. Available online: http://www.tunisie.gov.tn/37-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1.htm?ip=2&op=ACT_DATE+desc&cp=4e8e1b4a0a2c0b862bcb&mp=20 (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement, Ministère de la Santé. إجراءاتللحدّمنتداعياتفيروسكوروناالاقتصاديةوالاجتماعية. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a5%d8%ac%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%a1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%84%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%af%d9%91-%d9%85%d9%86-%d8%aa%d8%af%d8%a7%d8%b9%d9%8a%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%b1%d9%88%d8%b3-%d9%83%d9%88%d8%b1%d9%88%d9%86%d8%a7/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Institut, R.K. Mund-Nasen-Bedeckung im Öffentlichen Raum als Weitere Komponente zur Reduktion der Übertragungen von COVID-19. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2020/19/Art_02.html (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement. Ministère de la Santé. إحداثوحدةيقظةومتابعةالوضعالاجتماعيالعامالناجمعنتفشيفيروسكورونا. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a5%d8%ad%d8%af%d8%a7%d8%ab-%d9%88%d8%ad%d8%af%d8%a9-%d9%8a%d9%82%d8%b8%d8%a9-%d9%88%d9%85%d8%aa%d8%a7%d8%a8%d8%b9%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%88%d8%b6%d8%b9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%ac%d8%aa%d9%85%d8%a7/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement; Ministère de la Santé. Le Mardi 16 Mars 2020, les Dernières Mesures de Mr Elyes Fakhfekh. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/fr/blog/le-mardi-16-mars-2020-les-dernieres-mesures-de-mr-elyes-fakhfekh/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement; Ministère de la Santé. وزارةالنقلواللوجستيك: برنامجرحلاتعودةالتونسيينبالخارجالىأرضالوطن. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d9%88%d8%b2%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%86%d9%82%d9%84-%d9%88%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%84%d9%88%d8%ac%d8%b3%d8%aa%d9%8a%d9%83-%d8%a8%d8%b1%d9%86%d8%a7%d9%85%d8%ac-%d8%b1%d8%ad%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%b9/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement; Ministère de la santé. اجراءاتفتحالحدودالتونسيةبدايةمن 27 جوان 2020. 2020. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a7%d8%ac%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%a1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d9%81%d8%aa%d8%ad-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%af%d9%88%d8%af-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%aa%d9%88%d9%86%d8%b3%d9%8a%d8%a9/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Portail Covid19 Tunisie, R.T.; Présidence du Gouvernement; Ministère de la Santé. تنظيمدوراتتكوينيةعنبعدلفائدةمهنييالصحة. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%aa%d9%86%d8%b8%d9%8a%d9%85-%d8%af%d9%88%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%aa%d9%83%d9%88%d9%8a%d9%86%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%b9%d9%86-%d8%a8%d8%b9%d8%af-%d9%84%d9%81%d8%a7%d8%a6%d8%af%d8%a9-%d9%85%d9%87%d9%86%d9%8a/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- استكمالالتلاقيحالمدرسيةالخاصةبالسنةالدراسيةالحالية. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%a7%d8%b3%d8%aa%d9%83%d9%85%d8%a7%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%aa%d9%84%d8%a7%d9%82%d9%8a%d8%ad-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%af%d8%b1%d8%b3%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ae%d8%a7%d8%b5%d8%a9-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- حولالحجرالصحيالإجباريبالمراكزالمخصّصةللغرض. Available online: https://covid-19.tn/blog/%d8%ad%d9%88%d9%84-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%ac%d8%b1-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b5%d8%ad%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a5%d8%ac%d8%a8%d8%a7%d8%b1%d9%8a-%d8%a8%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%83%d8%b2-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Robert Koch Institut. Laborbasierte Surveillance von SARS-CoV-2. Wochenbericht vom 28.07.2020. Available online: https://ars.rki.de/Content/COVID19/Main.aspx (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Wartenberg, D.; Thompson, W.D. Privacy Versus Public Health: The Impact of Current Confidentiality Rules. Am. J. Public Health. 2010, 100, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, E. Germany’s Corona-virus Response: Separating Fact from Fiction. DW 2020, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Siewert, M.; Wurster, S.; Messerschmidt, L.; Cheng, C.; Buthe, T. A German Miracle? Crisis Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Multi-Level System. In PEX Special Report: Coronavirus Outbreak, Presidents’ Responses, and Institutional Consequences; 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3637013 (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Pierre Thielbörger, B.B. COVID-19 and the Basic Law: On the (Un)suitability of the German Constitutional “Immune System”. Available online: www.iconnectblog.com/covid-19-and-the-basic-law-on-the-unsuitability-of-the-german-constitutional-immune-system/ (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- König, L.P.F.T.; Der Föderalismus Wirkt. Zeit Online. Available online: https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/202005/corona-krise-deutschland-foederalismus-lokaleschutzmassnahmenlockerungen?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Ghanchi, A. Adaptation of the National Plan for the Prevention and Fight Against Pandemic Influenza to the 2020 COVID-19 Epidemic in France. Disaster. Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moatti, J.P. The French response to COVID-19: Intrinsic difficulties at the interface of science, public health, and policy. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaari, L.; Golubnitschaja, O. Covid-19 pandemic by the “real-time” monitoring: The Tunisian case and lessons for global epidemics in the context of 3PM strategies. EPMA J. 2020, 11, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Germain, M.; Caputo, F.; Metcalfe, S.; Tosi, G.; Spring, K.; Aslund, A.K.O.; Pottier, A.; Schiffelers, R.; Ceccaldi, A.; Schmid, R. Delivering the power of nanomedicine to patients today. J. Control Release 2020, 326, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouron, P.; Lancement de l’application StopCovid après l’avis positif de la CNIL. In Revue Européenne des Médias et du Numérique; 2020; pp. 5–8. Available online: https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02885791 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Maxwell, W.; L’outil de traçage StopCovid: Entre inefficacité et proportionnalité. Légipresse. 2020. Available online: https://hal.telecom-paris.fr/hal-02612317/document (accessed on 6 September 2020).

| Tunisia | Germany | France | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population in millions 2019 | 11.57 | 82.91 | 58.24 |

| Government type | Parliamentary republic | Federal parliamentary republic | Republic, semi-presidential |

| Life expectancy at birth in years (2018) | 77 | 81 | 83 |

| % Pop. over 65 years old (2019) | 9% | 22% | 20% |

| Prevalence of smoking (15 years old and over) | 32.7 (2016) | 30.6 (2016) | 32.7 (2016) |

| Type of Documents | References | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific articles | [22,23,24,25,26] | 5 | 7.7% | |

| Institutional Records | ||||

| Decrees | [27,28,29,30] | 4 | 6.6% | 92.3% |

| Web pages | [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] | 8 | 12.3% | |

| Devices, guides, and plans | [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] | 22 | 33.8% | |

| Articles | [61,62] | 2 | 3.1% | |

| Interview reports | [63,64,65] | 3 | 4.6% | |

| Press releases | [66,67] | 2 | 3.1% | |

| Situation points | [68,69,70] | 3 | 4.6% | |

| Information for citizens | [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] | 16 | 24.6% | |

| Total | 65 | 100% | ||

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Availability of a trigger for the activation and deactivation of a pandemic emergency response (and mechanism for updating) | Yes [28] | Yes [41] | Yes [30] |

| 1.2 Activation of a national response plan | Yes [40,71] | Yes [26,71] | Yes [38,40] |

| 1.3 National state of emergency | Yes [40,71] | Yes [21] | No [21] |

| 1.4 Use of reviews to strengthen the pandemic response | Yes [28,71] | Yes [43,74] | Yes [31] |

| 1.5 General lockdown (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S1)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| 1.6 Recommended physical distance between individuals in public spaces | Yes [75] | Yes [44] | Yes [63] |

| 1.7 Closure of public spaces (non-essential shops, restaurants, etc.) | Yes [76] | Yes [72] | Yes [22,24] |

| 1.8 Restrictions of the use of public transport (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S2)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| 1.9 Closure of workplaces (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S3)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| 1.10 Teleworking | Yes [77] | Yes [29] | Yes [45] |

| 1.11 Closure of educational institutions (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S4)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| 1.12 Interventions in place for risk groups and vulnerable population | Yes [78] | Yes [46] | Yes [47] |

| 1.13 Obligation to use face masks in the community in closed spaces | Yes [75] | Yes [72] | Yes [79] |

| 1.14 National movement restrictions (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S5)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| 1.15 Public gatherings restrictions (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S6)) | Yes [23] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 COVID-19 risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) plan in place | No data found | No data found | Yes [39,41] |

| 2.2 Mechanisms in place to routinely capture community feedback and assess public perceptions, concerns, and trust | Yes [48,71] | Yes [32,49] | Yes [68] |

| 2.3 Mechanisms in place to provide practical and logistical support to people living in socially vulnerable settings | Yes [80] | Yes [46,49] | Yes [39,66] |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Surveillance systems in place for comprehensive monitoring of COVID-19 epidemiology | Yes [28] | Yes [42] | Yes [31] |

| 3.2 Monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 virus characteristics | Yes [28] | Yes [42] | Yes [31] |

| 3.3 Estimates of infection prevalence from prevalence studies | No data found | Yes [61] | Yes [69] |

| 3.4 Testing strategies | Variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S7) [23] | ||

| 3.5 Monitoring of new confirmed cases by sex and age groups | Yes [36,40] | Yes [37,73] | Yes [31,38] |

| 3.6 Monitoring the number of probable and confirmed deaths due to COVID-19 and classification by sex and age groups | Yes [36,40] | Yes [37,73] | Yes [31,38] |

| 3.7 Availability of mobile app(s) to complement manual contact tracing | E7mi [33] | Stopcovid [34] | Corona warn app [35] |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 Presence of a public health emergency plan in PoE | Yes [30,70] | No data found | Yes [41] |

| 4.2 International travel management | Variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S8) | ||

| [23,60,70] | [23] | [23] | |

| 4.3 Containment strategy of passengers on repatriation flights during the border closure period. | Total closure of borders: 16 March [81] — Quarantine, in dedicated centers, enforced by the government, for all arrival passengers from abroad: 21 March–05 June [67,86] — Quarantine, in dedicated centers at the expense of arrival passengers from abroad: 5 June–27 June [82] — Border reopening 27 June [83] | Auto-quarantine recommended [64] | No data found |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 Preparation of laboratory capacity to manage large-scale COVID-19 testing (within the country or through international agreements) | No data found | Yes [50,72] | Yes [51] |

| 5.2 Laboratory numbers allowed until July 31 | No data found | No data found | 69 [87] |

| 5.3 Communication of number of people tested for COVID-19 per week | Yes [36,40] | Yes [37,73] | Yes [31,38] |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 Recommendation to have a clinical referral system in place to care for COVID-19 cases | Yes [52] | Yes [50,62] | Yes [53] |

| 6.2 Contact tracing strategy (variation over time (Supplementary Material Table S9)) | YES [24] | Yes [23] | Yes [23] |

| Indicator | Tunisia | France | Germany |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.1 Clinical guidance guide for treating COVID-19 patients | Yes [54] | Yes [50,55,56,88] | Yes [57] |

| 7.2 Isolation of confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases | Yes [40] | Yes [58,59] | Yes [39] |

| 7.3 Training healthcare professionals to manage COVID-19 patients | Yes [84] | Yes [27,50] | Yes [39] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laffet, K.; Haboubi, F.; Elkadri, N.; Georges Nohra, R.; Rothan-Tondeur, M. The Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Tunisia, France, and Germany: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Different National Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168622

Laffet K, Haboubi F, Elkadri N, Georges Nohra R, Rothan-Tondeur M. The Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Tunisia, France, and Germany: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Different National Strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168622

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaffet, Khouloud, Fatma Haboubi, Noomene Elkadri, Rita Georges Nohra, and Monique Rothan-Tondeur. 2021. "The Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Tunisia, France, and Germany: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Different National Strategies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168622

APA StyleLaffet, K., Haboubi, F., Elkadri, N., Georges Nohra, R., & Rothan-Tondeur, M. (2021). The Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Tunisia, France, and Germany: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Different National Strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168622