Analysis of the Impact of Disease Acceptance, Demographic, and Clinical Variables on Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Respondents

2.4. Variables

- (a)

- Demographic variables: age, sex, education, place of residence, and marital status.

- (b)

- Clinical variables: duration of disease, diabetes treatment method, presence and type of comorbidities, BMI, number of diabetes tablets per day, and the total number of tablets taken per day.

- (c)

- Psychological variables: the degree of acceptance of the AIS disease.

- (d)

- Self-care variables: health behavior (maintaining self-care), health control (monitoring self-care), glucose control (self-care management), and self-confidence in managing self-care.

- (e)

- Adherence to treatment recommendations variable: adherence level.

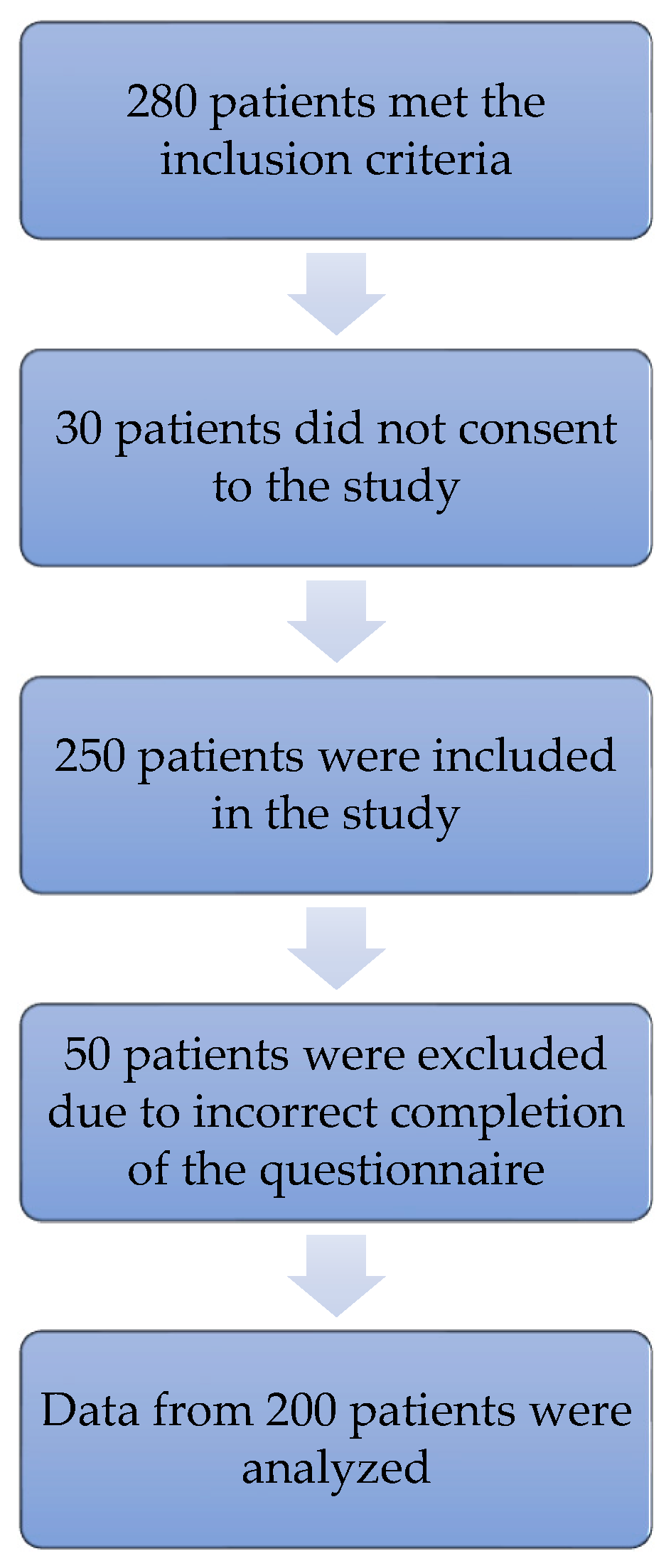

2.5. Study Size

2.6. Data Sources/Measurement

2.7. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. The Degree of Disease Acceptance, Self-Care Level Regarding Diabetes, and Adherence Level

3.3. Influence of Disease Acceptance on the Adherence to Therapeutic Recommendations and Self-Care Level

3.4. Factors Determining the Adherence Level—Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Results

4.2. Interpretation

4.2.1. Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients

4.2.2. Influence of Disease Acceptance on the Self-Care Level

4.2.3. Influence of Disease Acceptance on the Adherence to Therapeutic Recommendations

4.3. Generalizability

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- In the vast majority of elderly patients with T2DM, only a moderate or low level of adherence to therapeutic recommendations was observed; therefore, patients who have problems with the full implementation of the treatment plan should be identified as soon as possible and the causes of these problems should be sought.

- The level of disease acceptance in the study group was average, but it turned out to be an independent predictor of adherence. Therefore, it is justified to use psychological and behavioral interventions that are aimed at increasing the level of diabetes acceptance in the elderly with T2DM. Since psychophysical fitness decreases with age, it is important to implement a holistic approach to the patient and to take comprehensive actions, taking into account the patient’s deficits in the entire bio-psycho-social sphere to improve the effectiveness of the undertaken actions.

- Out of the self-care activities that were investigated, the patients were the worst at glucose and health control. However, on the positive side, patients’ self-reliance in these control areas increased as the level of disease acceptance increased. Thus, the obtained result confirmed the legitimacy of interventions that are aimed at increasing the level of disease acceptance in this group of patients.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas Committee. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, H.; Martin, S. Environmental/lifestyle factors in the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, A.; Saeedi, P.; Kaundal, A.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Williams, R. Diabetes and global ageing among 65-99-year-old adults: Findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Fund. Department of Analysis and Strategy. NHF about Health. Diabetes. Warsaw 2019. Available online: https://zdrowedane.nfz.gov.pl/course/view.php?id=45/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Williams, R.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Saeedi, P.; Basit, A.; Besançon, S.; Bommer, C.; Esteghamati, A.; Ogurtsova, K.; Zhang, P.; et al. Global and regional estimates and projections of diabetes-related health expenditure: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Rojas-Martinez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Hernández-Avila, M. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Mexico. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.S.; Laiteerapong, N.; Liu, J.Y.; John, P.M.; Moffet, H.H.; Karter, A.J. Rates of complications and mortality in older patients with diabetes mellitus: The diabetes and aging study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriere, M.; Rooparinesingh, N.; Kalyani, R.R. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetes complications in the elderly: An emerging public health burden. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013, 13, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, M.S.; Briscoe, V.J.; Clark, N.; Florez, H.; Haas, L.B.; Halter, J.B.; Huang, E.S.; Korytkowski, M.T.; Munshi, M.N.; Odegard, P.S.; et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2650–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehidoost, R.; Mansouri, A.; Amini, M.; Aminorroaya Yamini, S.; Aminorroaya, A. Diabetes and all-cause mortality, a 18-year follow-up study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.K.; Kontopantelis, E.; Emsley, R.; Buchan, I.; Sattar, N.; Rutter, M.K.; Ashcroft, D.M. Life Expectancy and Cause-Specific Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based Cohort Study Quantifying Relationships in Ethnic Subgroups. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clua-Espuny, J.L.; González-Henares, M.A.; Queralt-Tomas, M.; Campo-Tamayo, W.; Muria-Subirats, E.; Panisello-Tafalla, A.; Lucas-Noll, J. Mortality and Cardiovascular Complications in Older Complex Chronic Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6078498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoz, G.T.; Wahdey, S.; Bahrey, D.; Kahsay, H.; Woldu, G.; Niriayo, Y.L.; Collier, A. Predictors of poor adherence to antidiabetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study insight from Ethiopia. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badi, S.; Abdalla, A.; Altayeb, L.; Noma, M.; Ahmed, M.H. Adherence to Antidiabetic Medications Among Sudanese Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahouri, A.; Merrell, J.; Snelgrove, S. Barriers to good glycemic control levels and adherence to diabetes management plan in adults with Type-2 diabetes in Jordan: A literature review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, R.; Martins, S.; Fernandes, L. Adherence to Medication, Physical Activity and Diet in Older Adults with Diabetes: Its Association with Cognition, Anxiety and Depression. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2019, 11, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabate, E. Adherence to Long Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jemal, A.; Abdela, J.; Sisay, M. Adherence to Oral Antidiabetic Medications among Type 2 Diabetic (T2DM) Patients in Chronic Ambulatory Wards of Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Diabetes Metab. 2017, 8, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadele, K.; Abebe, A.; Teklebirhan, T.; Desalegn, S. Assessment of adherence to insulin self-administration and associated factors among type I diabetic patients at Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Endocrinol. Diabetes Res. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebaw, M.; Messele, A.; Hailu, M.; Zewdu, F. Adherence and Associated Factors towards Antidiabetic Medication among Type II Diabetic Patients on Follow-Up at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminde, L.N.; Tindong, M.; Ngwasiri, C.A.; Aminde, J.A.; Njim, T.; Fondong, A.A.; Takah, N.F. Adherence to antidiabetic medication and factors associated with non-adherence among patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in two regional hospitals in Cameroon. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2019, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaam, M.; Awaisu, A.; Mohamed Ibrahim, M.I.; Kheir, N. A holistic conceptual framework model to describe medication adherence in and guide interventions in diabetes mellitus. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besen, D.B.; Esen, A. Acceptance of Illness and Related Factors in Turkish Patients with Diabetes. Soc. Behavr. Pers. 2012, 40, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.S. Emotional adjustment to a chronic illness. Lippincott’s Prim. Care. Pract. 1998, 2, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, A.L.; Revenson, T.A.; Tennen, H. Health Psychology: Psychological Adjustment to Chronic Disease. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogon, I.; Kasprzak, Z.; Szcześniak, Ł. Perceived quality of life and acceptance of illness in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prz. Menopauzalny 2017, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia Pomiaru W Promocji I Psychologii Zdrowia; Wydanie II; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NFZ-Załącznik nr 1 Do Pisma Znak; WSOZ-II.0123.28.2018; National Health Fund: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- Ausili, D.; Barbaranelli, C.; Rossi, E.; Rebora, P.; Fabrizi, D.; Coghi, C.; Luciani, M.; Vellone, E.; Di Mauro, S.; Riegel, B. Development and Psychometric Testing of a Theory-Based Tool to Measure Self-Care in Diabetes Patients: The Self-Care for Diabetes Inventory. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2017, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchmanowicz, I.; Krzemińska, S.; Ausili, D.; Luciani, M.; Lisiak, M. Polish Adaptation of the Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI). Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubica, A.; Kosobucka, A.; Michalski, P.; Pietrzykowski, Ł.; Jurek, A.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Kasprzak, M. Skala adherence w chorobach przewlekłych—Nowe narzędzie do badania realizacji planu terapeutycznego. Folia Cardiol. 2017, 12, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office. Relative Concepts in Official Statistics: Older People; Poland; 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/metainformacje/slownik-pojec/pojecia-stosowane-w-statystyce-publycznej/3928,pojecie.html/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Alqarni, A.M.; Alrahbeni, T.; Qarni, A.A.; Qarni, H.M.A. Adherence to diabetes medication among diabetic patients in the Bisha governorate of Saudi Arabia—A cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 24, 63–71, Erratum in 2019, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, L.E.; Alvarez, M.; Dilla, T.; Gil-Guillén, V.; Orozco-Beltrán, D. Adherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2013, 4, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, A.; Śliż, D. Assessment of adherence to physician recommendations among patients with diagnosed diabetes mellitus type 2. Folia Cardiol. 2020, 3, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, W.H.; Henry, R.R. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: Recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Lim, S.L.; Goh, L.H.; Subramaniam, S.; Tangiisuran, B. Evaluation of illness perceptions and their associations with glycaemic control, medication adherence and chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Malaysia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi-Benedetti, M. CODE-2 Advisory Board. The cost of diabetes Type II in Europe: The CODE-2 Study. Diabetologia 2002, 45, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, W.; Han, H.R. Measuring Self-Care in Persons with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 39, 131–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzemińska, S.; Czapor, E. The level of self-care in patients with T2 diabetes using the Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI) questionnaire. Mod. Nurs. Health Care 2019, 8, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Olszak, C.; Nowicka, E.; Baczewska, B.; Łuczyk, R.; Kropornicka, B.; Krzyżanowska, E.; Daniluk, J. The influence of selected socio-demographic and medical factors on the acceptance of illness in a group of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Educ. Health Sport 2016, 6, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stefańska, M.; Majda, A. Religiousness and acceptance of the disease among persons with diabetes. Pol. Nurs. 2019, 2, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kurowska, K.; Lach, B. Akceptacja choroby i sposoby radzenia sobie ze stresem u chorych na cukrzycę typu 2. Diabetol. Pract. 2011, 12, 113–119. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, E.; Marcisz, C.; Krzemińska, S.; Dobrzyn-Matusiak, D.; Foltyn, A.; Drosdzol-Cop, A. Relationships of Sexual Dysfunction with Depression and Acceptance of Illness in Women and Men with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leporini, C.; De Sarro, G.; Russo, E. Adherence to therapy and adverse drug reactions: Is there a link? Expert. Opin. Drug. Saf. 2014, 13, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strojek, K.; Kurzeja, A.; Gottwald-Hostalek, U. Patient adherence to and tolerability of treatment with metformin extended-release formulation in patients with type 2 diabetes. GLUCOMP study. Clin. Diabetol. 2016, 5, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alhazmi, T.; Sharahili, J.; Khurmi, S.; Zughbi, T.; Alrefai, M.; Hakami, M.; Wasili, F.; Wadani, M.S.; Sahli, S.; Alhazmi, A.H.; et al. Drug Compliance among Type 2 Diabetic patients in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 5, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulmozhi, S.; Mahalakshmy, T. Self Care and Medication Adherence among Type 2 Diabetics in Puducherry, Southern India A Hospital Based Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haj Mohd, M.M.; Phung, H.; Sun, J.; Morisky, D.E. The predictors to medication adherence among adults with diabetes in the United Arab Emirates. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2016, 9, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aloudah, N.M.; Scott, N.W.; Aljadhey, H.S.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Alrubeaan, K.A.; Watson, M.C. Medication adherence among patients with Type 2 diabetes: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207583. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlar, N.; Lainscak, M.; Mårtensson, J.; Strömberg, A.; Jaarsma, T.; Farkas, J. Factors related to self-care behaviours in heart failure: A systematic review of European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale studies. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2017, 16, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, C.; Foo, R.; Singh, R.; Ozdemir, S.; Teo, I.; Sim, D.; Jaufeerally, F.; Aung, T.; Keong, Y.K.; Nadkarni, N.; et al. Study protocol for a cohort study of patients with advanced heart failure in Singapore. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowska, A.; Zozulińska-Ziółkiewicz, D.; Walczak, M.; Cyganek, K.; Wolnik, B.; Gawrecki, A.; Myśliwiec, M. Expert opinion: Implantable continuous glucose monitoring system—An innovation in the treatment of diabetes. Clin. Diabetol. 2019, 8, 318–328. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruttomesso, D.; Laviola, L.; Avogaro, A.; Bonora, E.; Del Prato, S.; Frontoni, S.; Orsi, E.; Rabbone, I.; Sesti, G.; Purrello, F. The Italian Diabetes Society (SID). The use of real time continuous glucose monitoring or flash glucose monitoring in the management of diabetes: A consensus view of Italian diabetes experts using the Delphi method. NMCD 2019, 29, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Demographic Variables | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M ± SD 1 | 70.21 ± 6.63 |

| Mdn 2 | 69 | |

| Q.25–Q.75% 3 | 65–74 | |

| Sex | Female | 101 (50.5%) |

| Male | 99 (49.5%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 65 (32.5%) |

| In a relationship | 135 (67.5%) | |

| Education | Elementary | 21 (10.5%) |

| Vocational | 49 (24.5%) | |

| Secondary | 93 (46.5%) | |

| Higher | 37 (18.5%) | |

| Place of residence | Countryside | 21 (10.5%) |

| City/town | 179 (89.5%) | |

| Clinical Variables | Values | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | M ± SD | 11.79 ± 8.36 |

| Mdn | 10 | |

| Q.25–Q.75% | 5–15 | |

| Diabetes treatment method | Oral diabetes medications | 123 (61.5%) |

| Insulin | 33 (16.5%) | |

| Oral medications + insulin | 38 (19.0%) | |

| Non-pharmacological methods | 6 (3.0%) | |

| Number of diabetes tablets per day | M ± SD | 1.86 ± 1.42 |

| Mdn | 2 | |

| Q.25–Q.75% | 1–3 | |

| Number of all tablets per day | M ± SD | 7.86 ± 4.45 |

| Mdn | 7 | |

| Q.25–Q.75% | 5–10 | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | Normal weight | 22 (11.0%) |

| Overweight | 76 (38.0%) | |

| Obesity—class 1 | 65 (32.5%) | |

| Obesity—class 2/class 3 | 37 (18.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Hypertension | No | 39 (19.5%) |

| Yes | 161 (80.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Ischemic heart disease | No | 129 (64.5%) |

| Yes | 71 (35.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Rheumatic diseases | No | 150 (75.0%) |

| Yes | 50 (25.0%) | |

| Comorbidities: Renal diseases | No | 163 (81.5%) |

| Yes | 37 (18.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Respiratory diseases | No | 159 (79.5%) |

| Yes | 41 (20.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Diseases of the locomotor system | No | 135 (67.5%) |

| Yes | 65 (32.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Diabetic foot syndrome | No | 157 (78.5%) |

| Yes | 43 (21.5%) | |

| Comorbidities: Eye diseases | No | 117 (58.5%) |

| Yes | 83 (41.5%) | |

| Tool | n | M 4 | SD 5 | Mdn 6 | Min 7 | Max 8 | Q.25% 9 | Q.75% 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACDS 1 | 200 | 23.4 | 3.66 | 24 | 13 | 28 | 21 | 26 | |

| AIS 2 | 200 | 28.52 | 7.48 | 29 | 8 | 40 | 24 | 34 | |

| SCODI 3 | Health behavior (self-care maintenance) | 200 | 68.35 | 15.41 | 68.75 | 31.25 | 100 | 58.33 | 77.60 |

| Health control (self-care monitoring) | 200 | 58.49 | 23.00 | 55.88 | 11.76 | 100 | 41.18 | 77.21 | |

| Glucose control (self-care management) | 200 | 40.68 | 22.15 | 38.89 | 8.33 | 150 | 22.22 | 55.56 | |

| Self-confidence in self-care management | 200 | 65.84 | 19.41 | 68.18 | 15.91 | 100 | 50.00 | 80.11 | |

| AIS 2 (Points) | ACDS 1 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Adherence (n = 42) A | Average Adherence (n = 114) B | High Adherence (n = 44) C | ||

| M ± SD 3 | 26.98 ± 8.05 | 27.83 ± 6.78 | 31.8 ± 7.86 | p = 0.002 * C > B, A |

| Mdn 4 | 29 | 29 | 33 | |

| Q.25–Q.75% 5 | 21–33 | 21–33 | 25–38.5 | |

| SCODI 1 | AIS 2 |

|---|---|

| Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient | |

| Health behavior | r = 0.103, p = 0.149 |

| Health control | r = 0.186, p = 0.009 * |

| Glucose control | r = 0.201, p = 0.004 * |

| Self-confidence | r = 0.134, p = 0.059 |

| Variable | OR 1 | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS | (points) | 0.903 | 0.846 | 0.963 | 0.002 * |

| Age | (years) | 1.058 | 0.974 | 1.15 | 0.181 |

| Sex | Female | 1 | ref. | ||

| Male | 2.269 | 0.888 | 5.8 | 0.087 | |

| Marital status | Single | 1 | ref. | ||

| In a relationship | 0.586 | 0.202 | 1.698 | 0.325 | |

| Education | Elementary | 1 | ref. | ||

| Vocational | 1.359 | 0.244 | 7.587 | 0.726 | |

| Secondary | 0.881 | 0.179 | 4.335 | 0.877 | |

| Higher | 1.537 | 0.241 | 9.794 | 0.649 | |

| Place of residence | Countryside | 1 | ref. | ||

| City/town | 1.542 | 0.376 | 6.329 | 0.548 | |

| BMI | Normal weight | 1 | ref. | ||

| Overweight | 0.367 | 0.059 | 2.265 | 0.28 | |

| Obesity—class 1 | 0.344 | 0.049 | 2.402 | 0.282 | |

| Obesity—class 2/class 3 | 0.466 | 0.054 | 4.007 | 0.487 | |

| Comorbidities: Arterial hypertension | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 1.082 | 0.305 | 3.84 | 0.903 | |

| Comorbidities: Ischemic heart disease | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.497 | 0.187 | 1.32 | 0.161 | |

| Comorbidities: Rheumatic diseases | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.896 | 0.294 | 2.729 | 0.847 | |

| Comorbidities: Renal diseases | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 1.816 | 0.495 | 6.661 | 0.368 | |

| Comorbidities: Respiratory diseases | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 1.094 | 0.351 | 3.406 | 0.877 | |

| Comorbidities: Diseases of the locomotor system | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.845 | 0.339 | 2.107 | 0.717 | |

| Comorbidities: Diabetic foot syndrome | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.691 | 0.217 | 2.201 | 0.531 | |

| Comorbidities: Eye diseases | No | 1 | ref. | ||

| Yes | 0.752 | 0.299 | 1.892 | 0.545 | |

| Duration of the disease | (years) | 1.05 | 0.98 | 1.125 | 0.168 |

| Diabetes treatment method | Oral diabetes medications | 1 | ref. | ||

| Insulin | 1.433 | 0.225 | 9.134 | 0.703 | |

| Oral medications + insulin | 0.637 | 0.182 | 2.231 | 0.48 | |

| Non-pharmacological methods | 0.998 | 0.061 | 16.241 | 0.999 | |

| Number of diabetes tablets per day | 1.708 | 0.857 | 3.401 | 0.128 | |

| Number of all tablets per day | 1.001 | 0.879 | 1.141 | 0.987 | |

| Variable | ACDS 1 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent (n = 44) | Non-Adherent (n = 156) | |||

| Age (years) | M ± SD 2 | 68.36 ± 6.37 | 70.73 ± 6.63 | p = 0.016 * |

| Mdn 3 | 67 | 69 | ||

| Q.25–Q.75%4 | 64–71.5 | 66–76 | ||

| Duration of the disease (years) | M ± SD | 9.52 ± 6.34 | 12.42 ± 8.75 | p = 0.063 |

| Mdn | 9 | 10 | ||

| Q.25–Q.75% | 5–12.5 | 5–17.25 | ||

| Number of diabetes tablets per day | M ± SD | 1.5 ± 1.09 | 1.96 ± 1.49 | p = 0.031 * |

| Mdn | 1.5 | 2 | ||

| Q.25–Q.75% | 1–2 | 1–3 | ||

| Number of all tablets per day | M ± SD | 7.45 ± 4.49 | 7.97 ± 4.45 | p = 0.586 |

| Mdn | 7.5 | 6 | ||

| Q.25–Q.75% | 3.75–9 | 5.75–10 | ||

| Sex | Female | 26 (59.09%) | 75 (48.08%) | p = 0.263 |

| Male | 18 (40.91%) | 81 (51.92%) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 10 (22.73%) | 55 (35.26%) | p = 0.166 |

| In a relationship | 34 (77.27%) | 101 (64.74%) | ||

| Education | Elementary | 5 (11.36%) | 16 (10.26%) | p = 0.606 |

| Vocational | 8 (18.18%) | 41 (26.28%) | ||

| Secondary | 24 (54.55%) | 69 (44.23%) | ||

| Higher | 7 (15.91%) | 30 (19.23%) | ||

| Place of residence | Countryside | 5 (11.36%) | 16 (10.26%) | p = 0.786 |

| City/town | 39 (88.64%) | 140 (89.74%) | ||

| BMI | Normal weight | 2 (4.55%) | 20 (12.82%) | p = 0.441 |

| Overweight | 17 (38.64%) | 59 (37.82%) | ||

| Obesity—class 1 | 17 (38.64%) | 48 (30.77%) | ||

| Obesity—class 2/class 3 | 8 (18.18%) | 29 (18.59%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Hypertension | No | 8 (18.18%) | 31 (19.87%) | p = 0.973 |

| Yes | 36 (81.82%) | 125 (80.13%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Ischemic heart disease | No | 27 (61.36%) | 102 (65.38%) | p = 0.754 |

| Yes | 17 (38.64%) | 54 (34.62%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Rheumatic diseases | No | 33 (75.00%) | 117 (75.00%) | p = 1 |

| Yes | 11 (25.00%) | 39 (25.00%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Renal diseases | No | 39 (88.64%) | 124 (79.49%) | p = 0.246 |

| Yes | 5 (11.36%) | 32 (20.51%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Respiratory diseases | No | 35 (79.55%) | 124 (79.49%) | p = 1 |

| Yes | 9 (20.45%) | 32 (20.51%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Diseases of the locomotor system | No | 28 (63.64%) | 107 (68.59%) | p = 0.662 |

| Yes | 16 (36.36%) | 49 (31.41%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Diabetic foot syndrome | No | 34 (77.27%) | 123 (78.85%) | p = 0.987 |

| Yes | 10 (22.73%) | 33 (21.15%) | ||

| Comorbidities: Eye diseases | No | 23 (52.27%) | 94 (60.26%) | p = 0.438 |

| Yes | 21 (47.73%) | 62 (39.74%) | ||

| Diabetes treatment method | Oral diabetes medications | 27 (61.36%) | 96 (61.54%) | p = 0.885 |

| Insulin | 7 (15.91%) | 26 (16.67%) | ||

| Oral medications + insulin | 8 (18.18%) | 30 (19.23%) | ||

| Non-pharmacological methods | 2 (4.55%) | 4 (2.56%) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonikowska, I.; Szwamel, K.; Uchmanowicz, I. Analysis of the Impact of Disease Acceptance, Demographic, and Clinical Variables on Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168658

Bonikowska I, Szwamel K, Uchmanowicz I. Analysis of the Impact of Disease Acceptance, Demographic, and Clinical Variables on Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168658

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonikowska, Iwona, Katarzyna Szwamel, and Izabella Uchmanowicz. 2021. "Analysis of the Impact of Disease Acceptance, Demographic, and Clinical Variables on Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168658

APA StyleBonikowska, I., Szwamel, K., & Uchmanowicz, I. (2021). Analysis of the Impact of Disease Acceptance, Demographic, and Clinical Variables on Adherence to Treatment Recommendations in Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168658