How Are Techno-Stressors Associated with Mental Health and Work Outcomes? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Information and Communication Technologies within the Technostress Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Technology Paradox

1.2. The Technostress Model

2. Materials and Methods

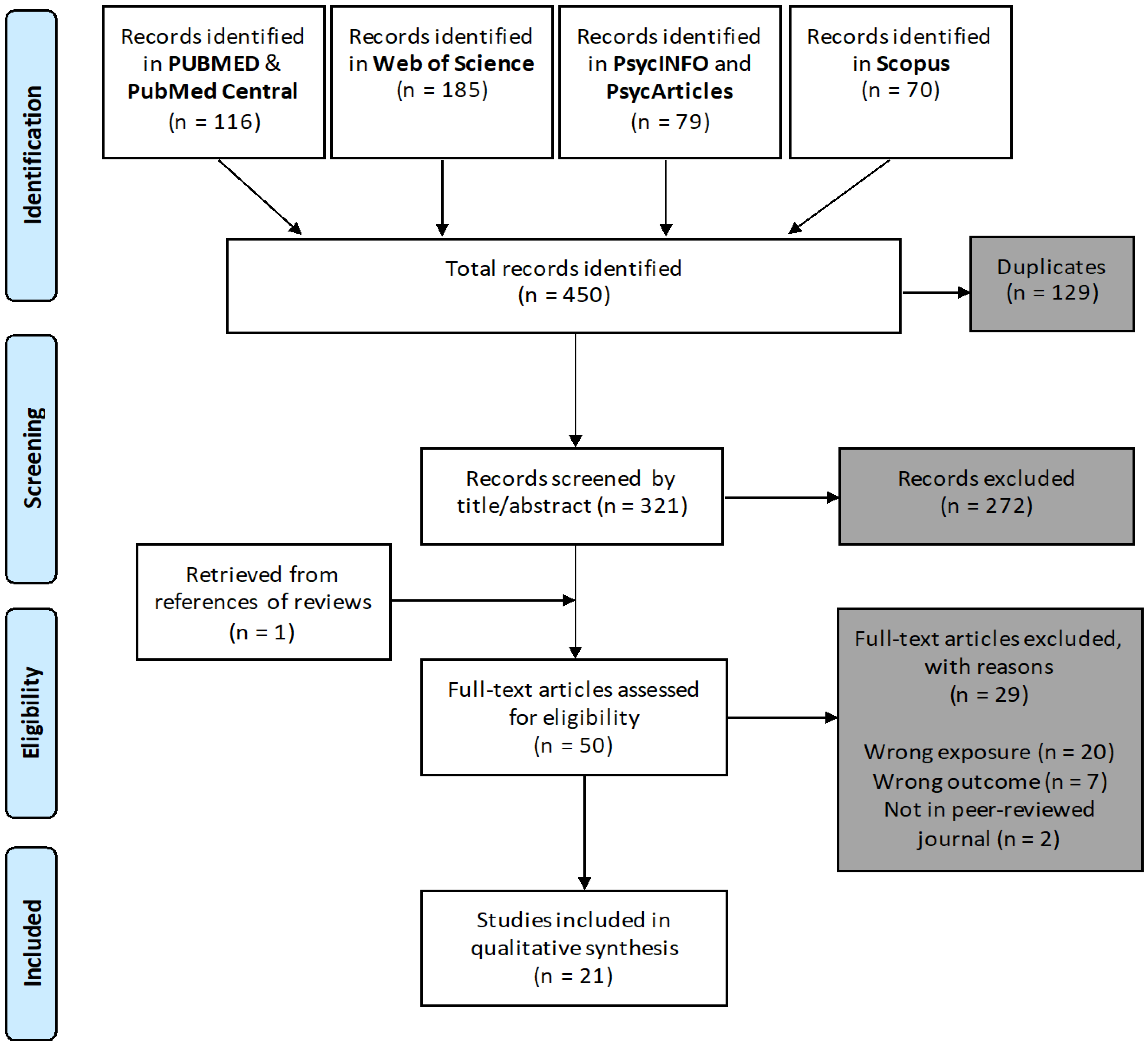

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

2.2. Data Collection and Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Quality Appraisal

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Associations with Health Outcomes

| First Author and Year | Techno-Stressor(s) | Health Outcome a | Findings Health a | N | Confounders | NOS Score b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadin et al. [23] 2019 | Techno-Overload Techno-Invasion (operationalised as ICT demands) | self-rated health (−) | Repeated exposure to overload was associated with increased risk of suboptimal SRH in the crude analysis (OR 1.36, CI [1.11–1.67]), also after adjustments (OR 1.34, CI [1.06–1.70]). Repeated exposure to high techno-overload was most prevalent among participants with high (40%), followed by participants with intermediate (35.5%) and low SEP (12.5%). | 4.468 | sex, age, SEP, health behaviours, BMI, job strain, social support | 9 c |

| Stadin et al. [24] 2016 | Techno-Overload Techno-Invasion (operationalised as ICT demands) | self-rated health (−) | Overload and invasion were associated with suboptimal self-rated health in crude analysis (OR 1.35 [CI 1.24–1.46]) also after adjustments (OR 1.49 [CI 1.36–1.63]). ICT demands were most prevalent among participants with high SES (59.8%), followed by participants with intermediate SES (54.9%) and low SES (29.1%). | 14.873 | sex, age, SEP, lifestyle factors | 9 |

| Goetz and Boehm [25] 2020 | Techno-Insecurity | self-rated health (−) | There was a significant time-lagged negative effect of insecurity on general health (B = −0.27, p < 0.001; F = 81.47, df = 3, p < 0.01). F = 11.84 **; R² (Fishers-z) = 0.125. | 8.019 | educational level, job position, age, gender disability status, working hours per week, organisational tenure, physical activity, occupational segment, companies’ operating sector | 8 |

| Ayyagari et al. [7] 2011 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Insecurity, Techno-Invasion | strain (+) | Overload (β = 0.26, p < 0.01) and insecurity (β = 0.10, p < 0.01) are positively associated with strain. Invasion is not associated with strain (β = 0.027, p > 0.05). | 661 | negative affectivity, technology usage | 8 |

| Day et al. [28] 2012 | Techno-Overload (operationalised as ICT demands) | strain, (n.s.) stress (+) | Overload was associated with increased stress (β = 0.26, p < 0.01). Overload was not associated with strain (β = 0.06, p < 0.01). ICT support was associated with better health outcomes. | 258 | age, gender, job tenure, of technologies used | 7 |

| Gaudioso et al. [34] 2017 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion | work exhaustion (+) | Overload (r = 0.50 **) and invasion (r = 0.35 **) were associated with increased work exhaustion. Significant indirect effects on work exhaustion of techno-overload (CI95 [0.154; −0.338], p < 0.004) and techno-invasion (CI95 [0.128; −0.356], p < 0.012). The effects are mediated via strain facets and coping strategies. | 242 | age, gender, daily hours of work | 7 |

| Srivastava et al. [8] 2015 | All | burnout (+) | Techno-stressors are positively associated with job burnout (β = 0.324, p < 0.01). | 152 | age, gender, location, experience, job demand, job control | 7 |

| Khedhaouria and Cucchi [32] 2019 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion, Techno-Insecurity | burnout (+) | Individuals may experience high job burnout when technostress situations are characterised by low invasion of privacy, high role ambiguity, and high job insecurity; low invasion of privacy, high work overload, role ambiguity, and job insecurity; high invasion of privacy, work overload, and role ambiguity; and high work overload and role ambiguity. | 161 | n. a. | 6 |

| Kim et al. [33] 2015 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion, Techno-Insecurity, Techno-Complexity | work exhaustion (+) | Overall techno-stressors (β = 0.327 ***) are positively associated with work exhaustion in mobile enterprise environments and work exhaustion is negatively associated with job satisfaction. Overload (β = 0.119, n.s.); invasion (β = 0.224 **); Insecurity (β = −0.019, n.s.); complexity (β = 0.107 ***). | 210 | age, gender, duration, job stressors | 6 |

| Wu et al. [30] 2020 | Techno-Invasion | negative emotion (+) | Invasion can significantly predict anxiety, (β = 0.27, p < 0.01). | 374 | age, gender, work experience, education, income, position | 6 |

| Suh and Lee [26] 2017 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion | strain (+) | Overload (β = 0.23 **) and invasion (β = 0.11 **) are positively associated with strain, which in turn reduces teleworkers’ job satisfaction (β = 0.40 ***) | 258 | age, gender, education | 5 |

| Florkowski [27] 2019 | Techno-Insecurity | stress (+) | Insecurity is positively associated with work stress (β = 0.37 ***) | 676 | no analyses of confounders despite collecting sociodemographic data | 4 |

| Lee [35] 2016 | Techno-Overload | negative emotion (+) | Overload is positively associated with negative emotion, i.e., anger (β = 0.622 **) and anxiety (β = 0.661 **) | 222 | age, gender | 4 |

| Jena [31] 2015 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion | negative emotion (+) | Overload and invasion are negatively associated with negative emotion (β = 0.25 **) | 216 | none | 3 |

3.4. Associations with Work Outcomes

| First Author and Year | Techno-Stressor(s) | Work Outcome a | Findings Work | Covariates | NOS Score b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vayre and Vonthron [40] 2019 | Techno-Invasion | work engagement (−) | Invasion is negatively associated with work engagement among executives and managers with high intensive use. | age, personal uses differences, socio-professional characteristics | 7 |

| Srivastava et al. [8] 2015 | All | work engagement (+) | Techno-stressors are positively associated with work engagement among executives and managers (β = 0.186, p < 0.05). | age, gender, location, experience, job demand, job control | 7 |

| Ragu-Nathan et al. [6] 2008 | All | job satisfaction (−) | Techno-stressors are negatively associated with job satisfaction (β = −0.13, p <0.01). | none | 6 |

| Kim et al. [33] 2015 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion, Techno-Insecurity, Techno-Complexity | job satisfaction (−) | Techno-stressors are positively associated with work exhaustion (β = 0.327, p < 0.01) in mobile enterprise environments, which in turn reduces job satisfaction (β = −0.149, p < 0.05). | age, gender, duration, job stressors | 6 |

| Suh and Lee [26] 2017 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion | job satisfaction (−) | Overload and invasion among teleworkers are negatively associated with strain, which in turn reduces job satisfaction (β = −0.040 p < 0.01). The manner in which technology and job characteristics influence teleworkers’ technostress varies depending on the intensity of teleworking. | age, gender, and education | 5 |

| Alam [39] 2016 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Complexity, Techno-Uncertainty | productivity (−) | Overload (β = −0.311, p < 0.05), complexity (β = −0.348, p < 0.05), and uncertainty (β = −0.165, p < 0.1), are negatively associated with productivity in aviation (R2 = 0.49 *). | none | 5 |

| Tarafdar et al. [37] 2015 | All | productivity (−) | Techno-stressors are negatively associated with productivity among salespersons (β = −0.147, p < 0.05). | education, organisational tenure, professional tenure | 5 |

| Tarafdar et al. [5] 2007 | All | productivity (−) | Techno-stressors are negatively associated with productivity (β = −0.280, p < 0.01). | none | 4 |

| Tarafdar et al. [38] 2011 | All | productivity (−) | Techno-stressors are negatively associated with productivity (β = −0.33, p < 0.01). | organisation | 4 |

| Florkowski [27] 2019 | Techno-Insecurity | job satisfaction (−) | Techno-insecurity is negatively associated with job satisfaction (β = −0.27, p < 0.01). | none | 4 |

| Al-Ansari and Alshare [36] 2019 | All | job satisfaction (−) | Techno-stressors decrease employee’s job satisfaction (β = −0.25, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.27). All sub-constructs were significant. Respondents reported low insecurity, i.e., fear of being replaced or unemployed by new technologies or by other employees who have a better understanding of new technologies. | none | 3 |

| Jena [31] 2015 | Techno-Overload, Techno-Invasion | job satisfaction (−) performance (−) | Overload and invasion are negatively associated with job satisfaction (β = −0.41, p < 0.01) and performance (β = −0.33, p < 0.05). | none | 3 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Health and Work Outcomes

4.2. Conceptual Developments

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author and Year | Country Data | Journal Discipline | Sample Type | N (RR) a | Gender (% men b) | Age | NOS Score | Techno- Overload (17) | Techno-Invasion (16) | Techno-Insecurity (11) | Techno-Complexity (8) | Techno-Uncertainty (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Ansari and Alshare [36] | Qatar | Information Systems | convenience | 410 (−) | 33% | Below 31 (37%); between 31 and 40 (32%); over 41 (31%) | 3 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Alam [39] | Pakistan | Information Systems | randomised | 203 (68%) | 82% | Not reported | 5 | x | x | x | ||

| Ayyagari, Grover and Purvis [7] | USA | Information Systems | randomised (online panel) | 661 (−) | 52% | M = 49 Mdn = 52 | 8 | x | x | x | ||

| Day, Paquet, Scott and Hambley [28] | Canada | Psychology | convenience | 258 (−) | 47% | M = 35 | 7 | x | ||||

| Florkowski [27] | USA | Information Systems | convenience | 177 (22%) | not reported | Not reported | 4 | x | ||||

| Gaudioso, Turel and Galimberti [34] | USA | Psychology | convenience | 242 (16%) | 28% | Modal age bracket: 45–54 years | 7 | x | x | |||

| Goetz and Boehm [25] | Germany | Information Systems | randomised (online panel) | 8019 (59%) | 51% | M = 44.3 (range: 18–77) | 8 | x | ||||

| Jena [31] | India | Information Systems | convenience | 216 (54%) | 54% | over 35 (53%); below 35 (47%) | 3 | x | x | |||

| Khedhaouria and Cucchi [32] | France | Information Systems | convenience | 465 (46%) | 50% | M = 39 (range: 24–62) | 6 | x | x | x | ||

| Kim, Lee, Yun and Im [33] | South Korea | social sciences | convenience | 210 (−) | 70% | over 40 (60%) | 6 | x | x | x | x | |

| Lee [29] | South Korea | Psychology | convenience | 222 (−) | 81% | 20–29 (1.7%), 30–34 (17.6%), 35–39 (17.1%), 40–44 (35.1%), 45–59 (22.5%) | 4 | x | ||||

| Ragu-Nathan, Tarafdar, Ragu-Nathan and Tu [6] | USA, India | Information Systems | convenience | 608 (89%) | 63% | below 45 (>50%) | 8 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Srivastava, Chandra and Shirish [8] | International | Information Systems | convenience | 152 (22%) | 76% | M = 37.96 (SD = 6.73) | 7 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Stadin, Nordin, Broström, Magnusson Hanson, Westerlund and Fransson [24] | Sweden | Public health | randomised (nationally representative) | 14,757 (53%) | 43% | Range: 20–75, younger people underrepresented | 9 | x | x | |||

| Stadin, Nordin, Brostrom, Hanson, Westerlund and Fransson [23] | Sweden | Public health | randomised (nationally representative) | 4468 (61%) | 43% | M 47.3 Most 40–59 | 9 | x | x | |||

| Suh and Lee [26] | South Korea | Information Systems | convenience | 258 (86%) | 57% | Not reported | 5 | x | x | |||

| Tarafdar, Tu, Ragu-Nathan and Ragu-Nathan [5] | USA | Information Systems | convenience | 237 (47%) | 17% | Not reported | 4 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Tarafdar, Tu and Ragu-Nathan [38] | USA | Information Systems | convenience | 233 (73%) | 17% | Not reported | 4 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Tarafdar, Pullins and Ragu-Nathan [37] | UK | Information Systems | convenience | 233 (73%) | 66% | Range: 26–56 | 5 | x | x | x | x | x |

| Vayre and Vonthron [39] | France | Psychology | convenience | 502 (67%) | ca. 50% | M = 40 | 7 | x | ||||

| Wu, Wang, Mei and Liu [30] | China | Information Systems | randomised (online panel) | 374 (62%) | 42% | 26–35 (75%) | 6 | x |

Appendix B

| (i) (occupational diseases [MH] OR occupational exposure [MH] OR occupational exposure * [TW] OR “occupational health” OR “occupational medicine” OR work-related OR working environment [TW] OR at work [TW] OR work environment [TW] OR occupations [MH] OR work [MH] OR workplace * [TW] OR workload OR occupation * OR worke * OR work place * [TW] OR work site * [TW] OR job * [TW] OR occupational groups [MH] OR employment OR worksite * OR industry) | AND | (ii) (technostress OR techno-stress)] |

References

- Wajcman, J. Pressed for Time: The Acceleration of Life in Digital Capitalism; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Iacono, C.S. Research commentary: Desperately seeking the “IT” in IT research—A call to theorizing the IT artifact. Inf. Syst. Res. 2001, 12, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E. The dark side of technologies: Technostress among users of information and communication technologies. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Star, S.L.; Strauss, A. Layers of Silence, Arenas of Voice: The Ecology of Visible and Invisible Work. Comput. Supported Coop. Work CSCW 1999, 8, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Tu, Q. The Consequences of Technostress for End Users in Organizations: Conceptual Development and Empirical Validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayyagari, R.; Grover, V.; Purvis, R. Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 35, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srivastava, S.C.; Chandra, S.; Shirish, A. Technostress creators and job outcomes: Theorising the moderating influence of personality traits. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 355–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.L.; Stich, J.-F. The technostress trifecta—techno eustress, techno distress and design: Theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazmanian, M.; Orlikowski, W.J.; Yates, J. The Autonomy Paradox: The Implications of Mobile Email Devices for Knowledge Professionals. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1337–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondanini, G.; Giorgi, G.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Munoz, A.; Andreucci-Annunziata, P. Technostress Dark Side of Technology in the Workplace: A Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Torre, G.; Esposito, A.; Sciarra, I.; Chiappetta, M. Definition, symptoms and risk of techno-stress: A systematic review. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Riedl, R. Technostress Research: A Nurturing Ground for Measurement Pluralism? Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2017, 40, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borle, P.; Reichel, K.; Voelter-Mahlknecht, S. Is There a Sampling Bias in Research on Work-Related Technostress? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Technostress and the Role of Socioeconomic Position. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, S.; Zanardi, F.; Baldasseroni, A.; Schaafsma, F.; Cooke, R.M.; Mancini, G.; Fierro, M.; Santangelo, C.; Farioli, A.; Fucksia, S.; et al. Search strings for the study of putative occupational determinants of disease. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 67, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nimrod, G. Technostress: Measuring a new threat to well-being in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsen, C.; Karanika-Murray, M.; Nardelli, G. Addressing mental health and organisational performance in tandem: A challenge and an opportunity for bringing together what belongs together. Work Stress 2020, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Nielsen, G.; Ladekjær Larsen, E. Use of information communication technology and stress, burnout, and mental health in older, middle-aged, and younger workers–results from a systematic review. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2017, 23, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bramer, W.M.; Giustini, D.; de Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Alvarez-Pasquin, M.J.; Diaz, C.; Del Barrio, J.L.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, A. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stadin, M.; Nordin, M.; Brostrom, A.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Westerlund, H.; Fransson, E. Repeated exposure to high ICT demands at work, and development of suboptimal self-rated health: Findings from a 4-year follow-up of the SLOSH study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2019, 92, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stadin, M.; Nordin, M.; Broström, A.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Westerlund, H.; Fransson, E.I. Information and communication technology demands at work: The association with job strain, effort-reward imbalance and self-rated health in different socio-economic strata. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2016, 89, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goetz, T.M.; Boehm, S.A. Am I outdated? The role of strengths use support and friendship opportunities for coping with technological insecurity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, A.; Lee, J. Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, G.W. HR technologies and HR-staff technostress: An unavoidable or combatable effect? Empl. Relat. 2019, 41, 1120–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A.; Paquet, S.; Scott, N.; Hambley, L. Perceived Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Demands on Employee Outcomes: The Moderating Effect of Organizational ICT Support. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Son, S.M.; Kim, K.K. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, N.; Mei, W.; Liu, L. Technology-induced job anxiety during non-work time: Examining conditional effect of techno-invasion on job anxiety. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2020, 22, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.K. Technostress in ICT enabled collaborative learning environment: An empirical study among Indian academician. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Cucchi, A. Technostress creators, personality traits, and job burnout: A fuzzy-set configurational analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.C.; Yun, H.; Im, K.S. An examination of work exhaustion in the mobile enterprise environment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 100, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudioso, F.; Turel, O.; Galimberti, C. The mediating roles of strain facets and coping strategies in translating techno-stressors into adverse job outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Does stress from cell phone use increase negative emotions at work? Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansari, M.A.; Alshare, K. The Impact of Technostress Components on the Employees Satisfaction and Perceived Performance: The Case of Qatar. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2019, 27, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Pullins, E.B.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. Technostress: Negative effect on performance and possible mitigations. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. Impact of technostress on end-user satisfaction and performance. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2011, 27, 303–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A. Techno-stress and productivity: Survey evidence from the aviation industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 50, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, E.; Vonthron, A.M. Identifying Work-Related Internet’s Uses—at Work and Outside Usual Workplaces and Hours—and Their Relationships With Work–Home Interface, Work Engagement, and Problematic Internet Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C. The Promotion of Technology Acceptance and Work Engagement in Industry 4.0: From Personal Resources to Information and Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baruch, Y. Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technol. Work Employ. 2000, 15, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.; Baroudi, J. Studying Information Technology in Organizations: Research Approaches and Assumptions. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, J.; Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Lu, C.-q. The impact of techno-stressors on work–life balance: The moderation of job self-efficacy and the mediation of emotional exhaustion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, S.; Arslan, A.; Kilinç, S. The moderating roles of technological self-efficacy and time management in the technostress and employee performance relationship through burnout. Inf. Technol. People 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkkalainen, H.; Salo, M.; Tarafdar, M.; Makkonen, M. Deliberate or Instinctive? Proactive and Reactive Coping for Technostress. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2019, 36, 1179–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Grote, G. Automation, Algorithms, and Beyond: Why Work Design Matters More Than Ever in a Digital World. Appl. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borle, P.; Boerner-Zobel, F.; Voelter-Mahlknecht, S.; Hasselhorn, H.M.; Ebener, M. The social and health implications of digital work intensification. Associations between exposure to information and communication technologies, health and work ability in different socio-economic strata. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 94, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, T.D. Publication Decisions and Their Possible Effects on Inferences Drawn from Tests of Significance—Or Vice Versa. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1959, 54, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. The “File Drawer Problem” and Tolerance for Null Results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tams, S.; Hill, K. Helping an old workforce interact with modern IT: A NeuroIS approach to understanding technostress and technology use in older workers. Lect. Notes Inf. Syst. Organ. 2017, 16, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, R. On the Biology of Technostress: Literature Review and Research Agenda. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2013, 44, 18–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borle, P.; Reichel, K.; Niebuhr, F.; Voelter-Mahlknecht, S. How Are Techno-Stressors Associated with Mental Health and Work Outcomes? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Information and Communication Technologies within the Technostress Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168673

Borle P, Reichel K, Niebuhr F, Voelter-Mahlknecht S. How Are Techno-Stressors Associated with Mental Health and Work Outcomes? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Information and Communication Technologies within the Technostress Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168673

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorle, Prem, Kathrin Reichel, Fiona Niebuhr, and Susanne Voelter-Mahlknecht. 2021. "How Are Techno-Stressors Associated with Mental Health and Work Outcomes? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Information and Communication Technologies within the Technostress Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168673

APA StyleBorle, P., Reichel, K., Niebuhr, F., & Voelter-Mahlknecht, S. (2021). How Are Techno-Stressors Associated with Mental Health and Work Outcomes? A Systematic Review of Occupational Exposure to Information and Communication Technologies within the Technostress Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168673