Changes in Adolescents’ Psychosocial Functioning and Well-Being as a Consequence of Long-Term COVID-19 Restrictions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Procedure

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Measures

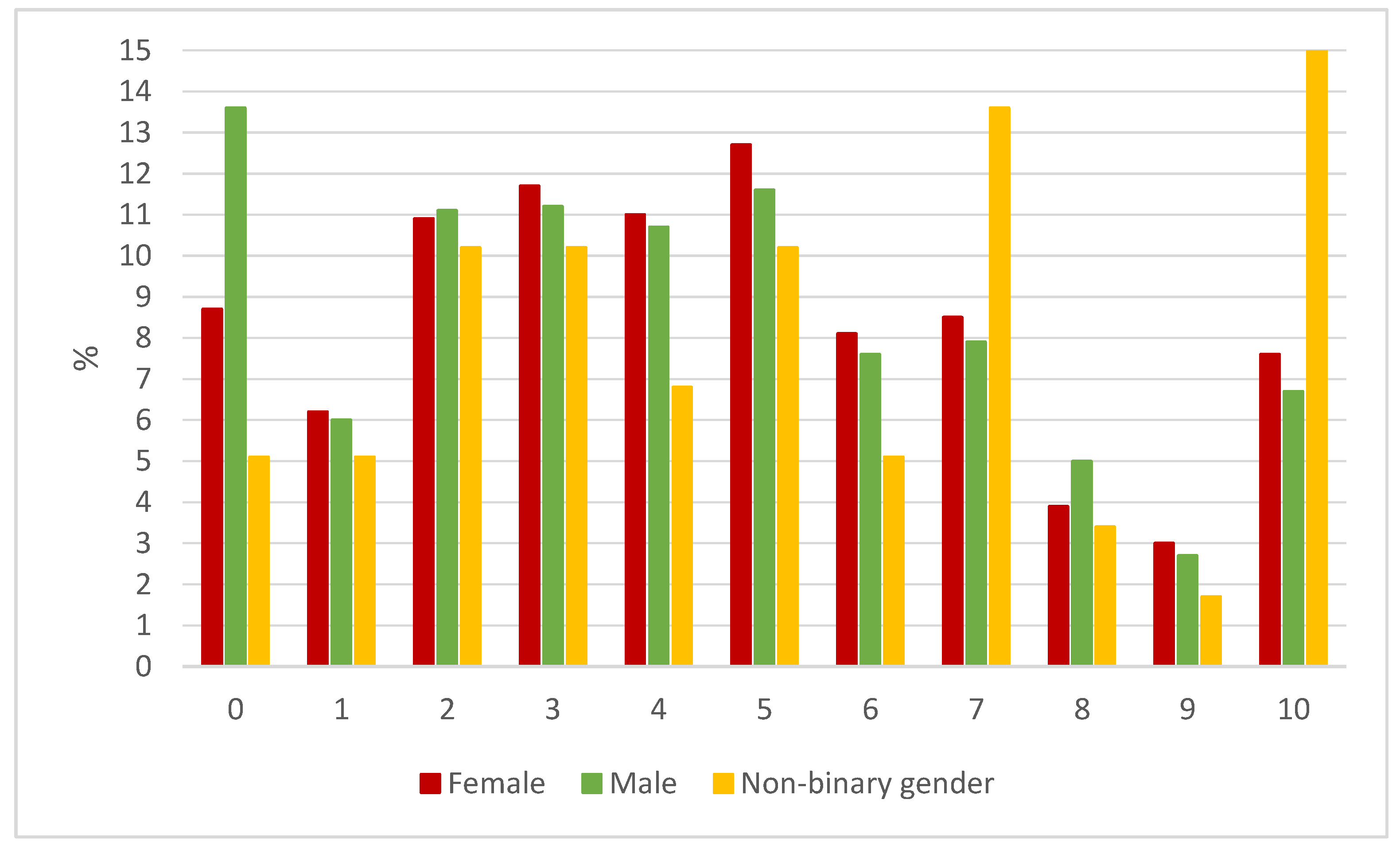

- COVID impact. One item measured the personal overall impact of COVID-19 on the adolescents’ lives, expressed on a numeric analogue scale, between 0 “slightly or no affect” and 10 “has affected me immensely”.

- Changes in Adolescents’ Behaviors. Adolescents reported changes concerning substance use (4 items), relations with family and friends (6 items), everyday life situations (5 items), and norm-breaking behaviors (2 items). Responses to each item were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1—decreased a lot, 2—decreased somewhat, 3—about the same as before, 4—increased somewhat, and 5—increased a lot. The participants could choose the option “I did not do this before the outbreak and have not started” and this response was coded as 0.

- Changes in Adolescents’ Mental Health. Ten items from the “Experiences Related to COVID-19 instrument” [14] were used to assess adolescents’ reported changes in sleep, stress, satisfaction, loneliness, involvement in society, and a different affect. The internal consistency was acceptable for this scale in the Swedish adolescent population (α = 0.82) [8], while it was low in our global study population (α = 0.53). The items were measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 4 (agree completely).

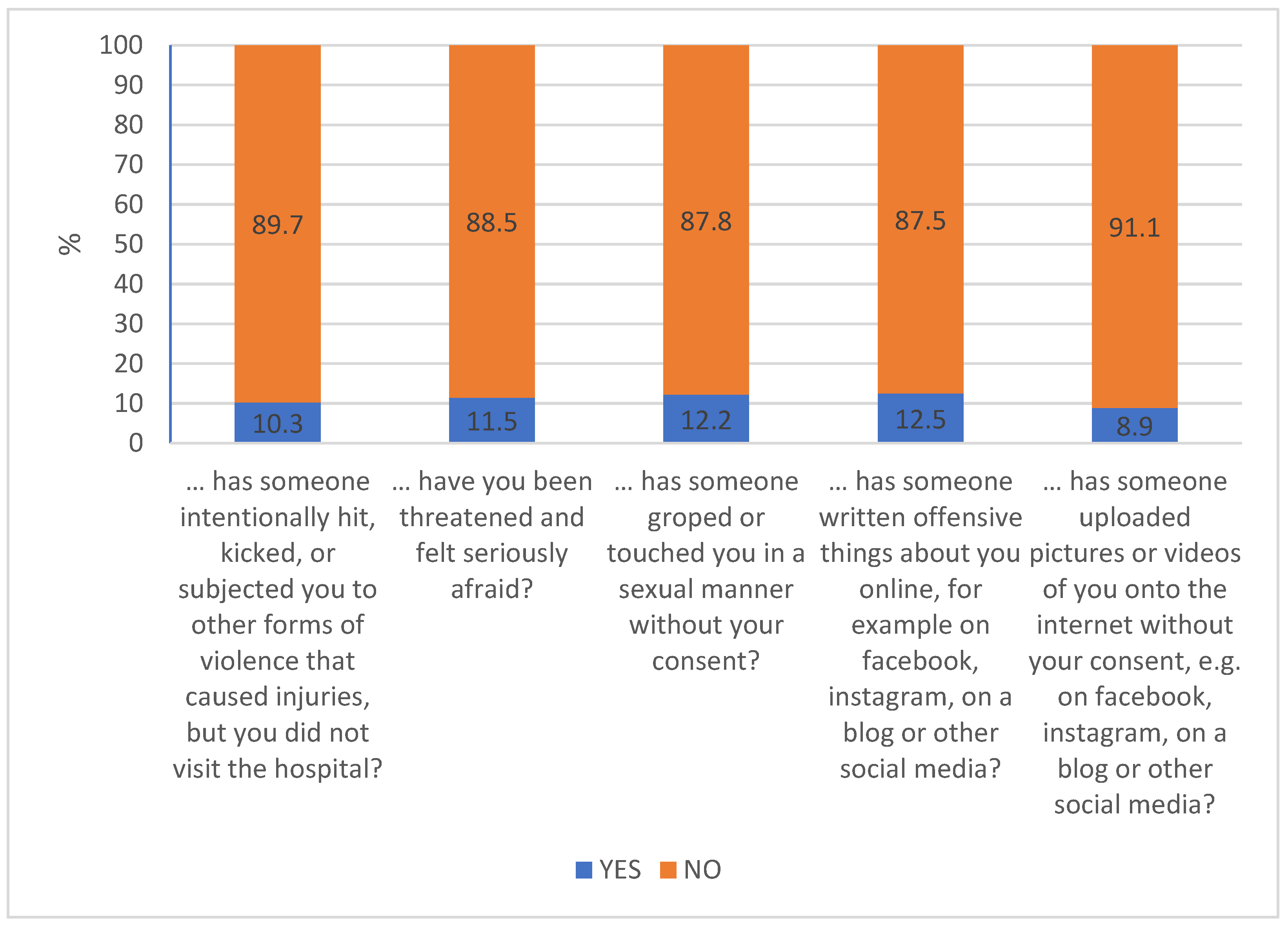

- Changes in Adolescents’ Victimization. Changes in the frequency of victimization were assessed with five items selected from the Swedish Crime Survey [15] and previously used in an epidemiological study by Kapetanovic et al. [8]. The items assessed physical violence, threats, and sexual harassment (3 items) and online victimization (2 items), measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (decreased a lot) to 5 (increased a lot). The scales previously showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.92) [8], which was similar to ours (α = 0.92).

2.4. Data Analysis

- Factor 1 related to risk behaviors included the items consuming alcohol; getting intoxicated by alcohol; smoking cigarettes; staying outside/being in the city without your parents’ knowledge; being outside and (for example) taking walks; with Cronbach’s α of 0.66.

- Factor 2 salutogenic approaches included the items having the opportunity to be in control over my daily life; keeping up with school projects and/or work; spending time doing things that I did not have time to do before; working out or exercising; spending time with family; and taking part in fun activities; with Cronbach’s α of 0.66.

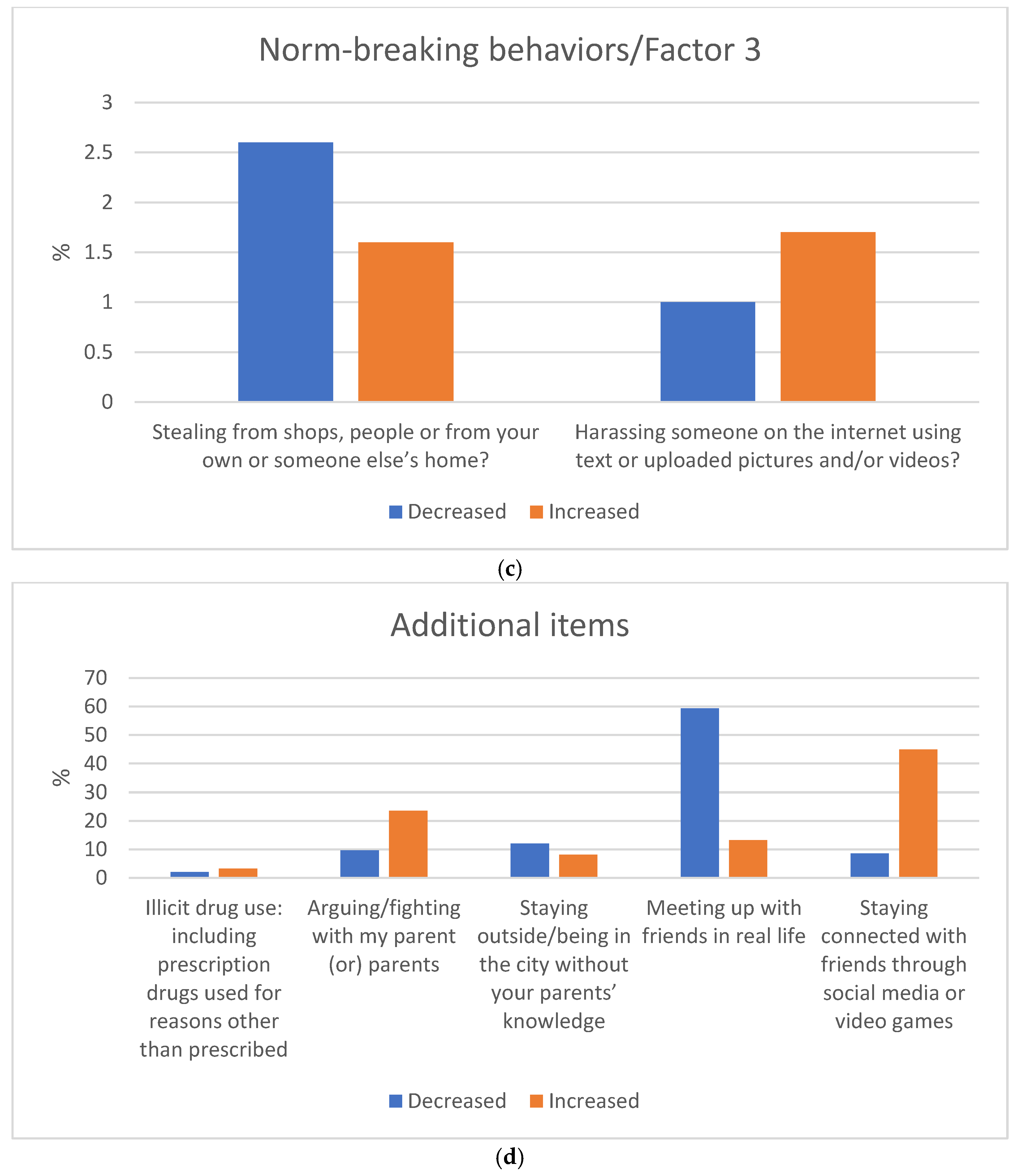

- Factor 3 related to norm-breaking included the items stealing from shops, people or from your own or someone else’s home; and harassing someone on the internet using written language or uploaded pictures and/or videos; with Cronbach’s α of 0.64. The overall reliability for the remaining items (illicit drug use including prescription drugs used for reasons other than prescribed; staying in contact with relatives and friends over the phone/internet; staying connected with friends through social media or video games; arguing/fighting with my parent (or) parents; meeting up with friends in real life) was α = 0.60.

3. Results

3.1. The Overall Impact of COVID-19 on Adolescents

3.2. Changes in Adolescents’ Behaviors

3.3. Changes in Adolescents’ Mental Health

3.4. Changes in Adolescents’ Victimization

4. Discussion

4.1. COVID-19 Restrictions’ Impact on Adolescent Mental Health, Behaviors, and Psychological Functioning

4.2. Victimization

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ludvigsson, J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, J.; Sinha, I.; Mburugu, P.; Agweyu, A.; Emadau, C.; Akech, S.; Kithuci, R.; Oyiengo, L.; English, M. Is the effect of COVID-19 on children underestimated in low- and middle- income countries? Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paus, T.; Keshavan, M.; Giedd, J.N. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Ritchie, R.A.; Meca, A.; Schwartz, S.J. Adolescent identity: Is this the key to unraveling associations between family relationships and problem behaviors? In Parenting and Teen Drug Use; Scheier, L.M., Hansen, W.B., Scheier, L.M., Hansen, W.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 92–109. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, D.; Reyna, V.F.; Satterthwaite, T.D. Beyond stereotypes of adolescent risk taking: Placing the adolescent brain in developmental context. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017, 27, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Korczak, D.J.; McArthur, B.; Madigan, S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: A rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, C.S.; Sandre, P.C.; Portugal, L.C.L.; Mázala-de-Oliveira, T.; da Silva Chagas, L.; Raony, Í.; Ferreira, E.S.; Giestal-de-Araujo, E.; Dos Santos, A.A.; Bomfim, P.O. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog. Neuro—Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 106, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, S.; Gurdal, S.; Ander, B.; Sorbring, E. Reported changes in adolescent psychosocial functioning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Adolescents 2021, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.A.K.; Mitra, A.K.; Bhuiyan, A.R. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, T.M.; Ellis, W.; Litt, D.M. What does adolescent substance use look like during the COVID-19 pandemic? Examining changes in frequency, social contexts, and pandemic-related predictors. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MeSHe. Mental and Somatic Health Without Borders Project. Available online: https://meshe.se/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Skinner, A.T.; Lansford, J.E. Experiences related to COVID-19. 2020; Unpublished Measure. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, J. Brott bland ungdomar i årskurs nio (Crime and problem behaviours among year-nine youths in Sweden). In Resultat Från Skolundersökningen om Brott Åren 1995–2011; Brottsförebyggande Rådet—BRÅ (The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention): Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kola, L.; Kohrt, B.A.; Hanlon, C.; Naslund, J.A.; Sikander, S.; Balaji, M.; Benjet, C.; Cheung, E.Y.L.; Eaton, J.; Gonsalves, P.; et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: Reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijzerman, H.; Lewis, N.A.J.; Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N.; DeBruine, L.; Ritchie, S.J.; Vazire, S.; Forscher, P.S.; Morey, R.D.; Ivory, J.D.; et al. Use caution when applying behavioural science to policy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessoum, S.B.; Lachal, J.; Radjack, R.; Carretier, E.; Minassian, S.; Benoit, L.; Moro, M.R. Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Xin, S.; Luan, D.; Zou, Z.; Bai, X.; Liu, M.; Gao, Q. Independent and combined associations between screen time and physical activity and perceived stress among college students. Addict. Behav. 2020, 103, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.P.; Gregory, A.M. Editorial perspective: Perils and promise for child and adolescent sleep and associated psychopathology during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aylie, N.S.; Mekonen, M.A.; Mekuria, R.M. The psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic among university students in Bench-Sheko zone, South-west Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, K.D.; Exner-Cortens, D.; McMorris, C.A.; Makarenko, E.; Arnold, P.; Van Bavel, M.; Williams, S.; Canfield, R. COVID-19 and student well-being: Stress and mental health during return-to-school. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler-Kuo, M.; Dzemaili, S.; Foster, S.; Werlen, L.; Walitza, S. Stress and mental health among children/adolescents, their parents, and young adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankin, B. Development of sex differences in depressive and co-occurring anxious symptoms during adolescence: Descriptive trajectories and potential explanations in a multiwave prospective study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohannessian, C.M.; Milan, S.; Vannucci, A. Gender differences in anxiety trajectories from middle to late adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 46, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouini, B.; Sfendla, A.; Ahlström, B.H.; Senhaji, M.; Kerekes, N. Mental health profile and its relation with parental alcohol use problems and/or the experience of abuse in a sample of Moroccan high school students: An explorative study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2019, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerekes, N.; Zouini, B.; Tinbetg, S.; Erlandsson, S.I. Psychological distress, somatic complaints and their relation to negative psychosocial factors in a sample of Swedish high school students. Front. Public Health 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landstedt, E.; Asplund, K.; Gådin, K.G. Understanding adolescent mental health: The influence of social processes, doing gender and gendered power relations. Sociol. Health Illn. 2009, 31, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Kiuru, N.; Pietikäinen, M.; Jokela, J. Does school matter? The role of school context in adolescents’ school-related burnout. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. Social isolation and loneliness of older adults in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Can use of online social media sites and video chats assist in mitigating social isolation and loneliness? Gerontology 2021, 67, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Healthy at Home—Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/campaigns/connecting-the-world-to-combat-coronavirus/healthyathome/healthyathome---physical-activity (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Rundle, A.G.; Park, Y.; Herbstman, J.B.; Kinsey, E.W.; Wang, Y.C. COVID-19–related school closings and risk of weight gain among children. Obesity 2020, 28, 1008–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet 2020, 395, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, L.; Shaw, K.A.; Ko, J.; Deprez, D.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Zello, G.A. The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on university students’ dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, J.; Seto, S.; Fukuda, Y.; Funakoshi, S.; Amae, S.; Onobe, J.; Izumi, S.; Ito, K.; Imamura, F. Mental health and physical activity among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2021, 253, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Kang, S.; Qiu, L.; Lu, Z.; Sun, Y. Association between physical activity and mood states of children and adolescents in social isolation during the COVID-19 epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, X.; Qi, H.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, G. Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijneveld, S.A.; Crone, M.R.; Schuller, A.A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P. The changing impact of a severe disaster on the mental health and substance misuse of adolescents: Follow-up of a controlled study. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbone, F.G.; Larison, C.L. A bibliographic essay: The relationship between stress and substance use. Subst. Use Misuse 2000, 35, 757–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Fried, E.I.; Eaton, N.R. The association of life stress with substance use symptoms: A network analysis and replication. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2020, 129, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.F. Delay of gratification, coping with stress, and substance use in adolescence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993, 1, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S. Youth and the opioid epidemic. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemma, V.A.; Chapple, K.M.; Goslar, P.W.; Israr, S.; Petersen, S.R.; Weinberg, J.A. Crisis under the radar: Illicit amphetamine use is reaching epidemic proportions and contributing to resource overutilization at a Level I trauma center. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 85, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D. America’s addiction to opioids: Heroin and prescription drug abuse. In Proceedings of the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, Washington, DC, USA, 14 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, W.M.; Volkow, N.D. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: Concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006, 81, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.; Lancaster, K.; Hughes, C. The stigmatisation of ‘ice’ and under-reporting of meth/amphetamine use in general population surveys: A case study from Australia. Int. J. Drug Policy 2016, 36, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, J.K.; Gudin, J.; Radcliff, J.; Kaufman, H.W. The opioid epidemic within the COVID-19 pandemic: Drug testing in 2020. Popul. Health Manag. 2021, 24, S-43–S-51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 48, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cater, A.K.; Andershed, A.K.; Andershed, H. Youth victimization in Sweden: Prevalence, characteristics and relation to mental health and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2014, 38, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, M.K.; Ehrenreich, S.E. The power and the pain of adolescents’ digital communication: Cyber victimization and the perils of lurking. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.; Gopal, N. Cyberbullying perpetration: Children and youth at risk of victimization during Covid-19 lockdown. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2021, 10, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; Daigneault, I.; Hébert, M. Lessons learned from child sexual abuse research: Prevalence, outcomes, and preventive strategies. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, E.J.; Erkanli, A.; Fairbank, J.A.; Angold, A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. J. Trauma Stress 2002, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, D.; Hamby, S.; Ormrod, R.; Turner, H. The juvenile victimization questionnaire: Reliability, validity, and national norms. Child. Abuse Negl. 2005, 29, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, R.; Widom, C.S.; Browne, K.; Fergusson, D.; Webb, E.; Janson, S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009, 373, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, F.W. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annerbäck, E.M.; Wingren, G.; Svedin, C.G.; Gustafsson, P.A. Prevalence and characteristics of child physical abuse in Sweden—Findings from a population-based youth survey. Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May-Chahal, C. Gender and child maltreatment: The evidence base. Soc. Work. Soc. 2006, 4, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

| N between 5018–4962 | No Change (%) | Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 Risk Behavior | Smoking cigarettes | 90.5 | 9.5 |

| Consuming alcohol | 76.5 | 23.5 | |

| Getting intoxicated by alcohol | 83.9 | 16.1 | |

| Staying outside/being in the city without your parents’ knowledge | 46.7 | 53.3 | |

| Being outside and taking walks (for example) | 29.4 | 70.6 | |

| Factor 2 Salutogenic Approach | Spending time with family taking part in fun/quality activities | 40.9 | 59.1 |

| Spending time to do things I have not had the time to do before | 40.6 | 59.4 | |

| Keeping up with school projects and/or work | 43.8 | 56.2 | |

| Having the opportunity to have control over my daily life | 42.9 | 57.1 | |

| Working out or exercising | 38.3 | 61.7 | |

| Factor 3 Norm-breaking Behavior | Stealing from shops, people or from your own or someone else’s home | 95.7 | 4.3 |

| Harassing someone on the internet using text or uploaded pictures and/or videos | 97.3 | 2.7 | |

| Additional items | Illicit drug use: including prescription drugs used for reasons other than prescribed | 94.7 | 5.3 |

| Arguing/fighting with my parent (or) parents | 66.7 | 33.3 | |

| Meeting up with friends in real life | 27.4 | 72.6 | |

| Staying in contact with relatives and friends over the phone/internet | 79.8 | 20.2 | |

| Staying connected with friends through social media or video games | 46.5 | 53.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kerekes, N.; Bador, K.; Sfendla, A.; Belaatar, M.; Mzadi, A.E.; Jovic, V.; Damjanovic, R.; Erlandsson, M.; Nguyen, H.T.M.; Nguyen, N.T.A.; et al. Changes in Adolescents’ Psychosocial Functioning and Well-Being as a Consequence of Long-Term COVID-19 Restrictions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168755

Kerekes N, Bador K, Sfendla A, Belaatar M, Mzadi AE, Jovic V, Damjanovic R, Erlandsson M, Nguyen HTM, Nguyen NTA, et al. Changes in Adolescents’ Psychosocial Functioning and Well-Being as a Consequence of Long-Term COVID-19 Restrictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168755

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerekes, Nóra, Kourosh Bador, Anis Sfendla, Mohjat Belaatar, Abdennour El Mzadi, Vladimir Jovic, Rade Damjanovic, Maria Erlandsson, Hang Thi Minh Nguyen, Nguyet Thi Anh Nguyen, and et al. 2021. "Changes in Adolescents’ Psychosocial Functioning and Well-Being as a Consequence of Long-Term COVID-19 Restrictions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168755

APA StyleKerekes, N., Bador, K., Sfendla, A., Belaatar, M., Mzadi, A. E., Jovic, V., Damjanovic, R., Erlandsson, M., Nguyen, H. T. M., Nguyen, N. T. A., Ulberg, S. F., Kuch-Cecconi, R. H., Szombathyne Meszaros, Z., Stevanovic, D., Senhaji, M., Hedman Ahlström, B., & Zouini, B. (2021). Changes in Adolescents’ Psychosocial Functioning and Well-Being as a Consequence of Long-Term COVID-19 Restrictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8755. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168755