Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

- How do you feel that social media can be a positive factor in the lives of adolescents?

- How do you feel that social media can be a negative factor in the lives of adolescents?

2.3. Data Analysis

- Phase 1: Three of the authors (GJH, RTH, and BEVA) read and re-read the material and noted potential themes.

- Phase 2: The same three authors identified relevant text segments and created codes individually. Subsequently, the suggested codes were discussed in plenary and a final list of codes was made. BEVA used the agreed-upon codes to code the transcripts. The coding was performed in Nvivo, version 12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

- Phase 3: GJH, RTH, BEVA, and JCS independently sorted the codes into potential topics. VS provided an external perspective on the themes, following which we agreed on a set of topics.

- Phase 4: BEVA took the main responsibility for reviewing the topics in relation to the coded text segments and the entire data set (the transcribed interviews). The themes were discussed in face-to-face meetings with GJH, RTH, VS, and JCS.

- Phase 5: When a consensus about the themes was reached, the themes were collaboratively named and defined by all the authors.

- Phase 6: BEVA prepared the first draft, which was further processed and completed under the leadership of GJH and in collaboration with all the authors.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

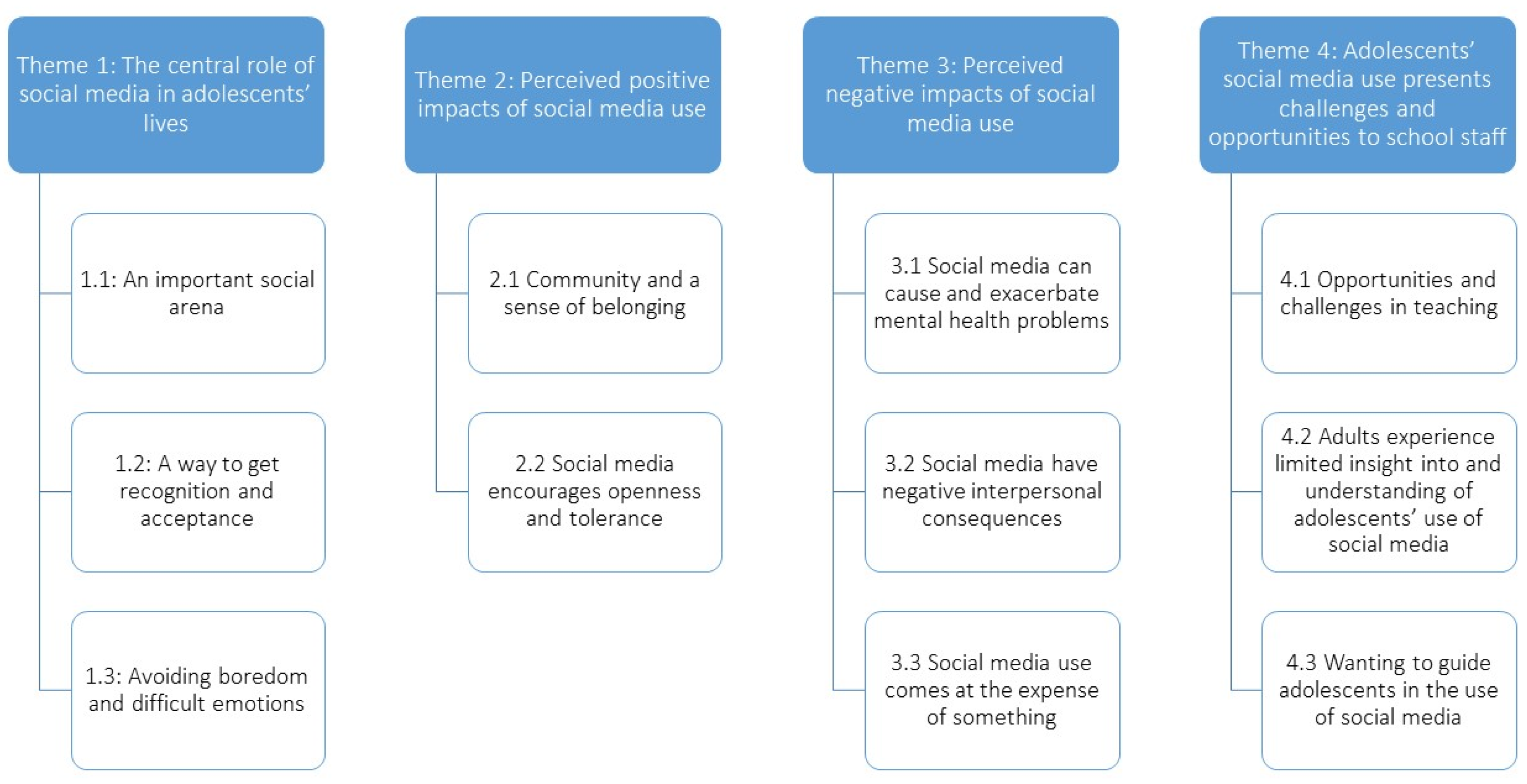

3. Results

Findings

I think the word there is community. They feel that, that’s where they communicate, that’s where they are. And if they are not there, then they may be the only one in their class who is not there. And that isolates them very much. (FG2F1)

I think that there is a basic psychological need that can be fulfilled by social media, for example when you talk about likes, then, that is about acceptance and recognition. (FG1M1)

It is the need for safety. The phone is a safe space for them, because then they don’t have to meet others’ gaze when they are on the bus, for example. Then they can look at their phone instead. (FG1F2)

For those who have previously lived a very isolated and secluded life, mostly alone in their room, then social media may be sort of a crack in the wall where a little light comes in. (FG1M1)

It is an arena where, or… where they meet each other. And in there, they’re all the same, in a way. They don’t see each other, it’s just “that person there”, in a way. If you understand. You kind of don’t see that “he’s in a wheelchair” or “she looks like that”. It’s just “what are your thoughts?” instead of. (FG2M1)

I think that living up to the image they really want of themselves, it does something with their mental state, because there are lots of influencers who tell you how to eat, what to eat, how to exercise, what to… and it becomes difficult to live up to it. It can affect their self-image, I think. (FG1F2)

And I feel that, it seems as if more and more people have less empathy. People no longer care about what those at the other end receive or how they express themselves. And the things they say online that they would never say face-to-face. (FG2M3)

I think that what you are describing is not something new; it is not something that has occurred due to social media. But it’s just that now it is more visible. For us too, there was exclusion, there were people who were excluded and people who were included. But now it is manifested through social media. (FG1M1)

But I worry about what they miss when they are reading body language, for example. When they don’t, uh, talk to each other anymore, everything goes through social media. (FG1F2)

But I think that perhaps the solution would be to have, in a way, tasks that take into account that the information is there and is easily accessible, but that they have to use creativity and use their own experiences and reasoning to be able to answer the assignments. (FG6M3)

Because some students focus too much on it. If it’s not gaming, it’s the phone. And it is very challenging for us to create a calm and peaceful atmosphere in the classroom. (FG1F2)

FG1M1: But it is also not allowed to use the phone during class

FG1M3: No, that’s true. But what do we do then?

FG1M1: Yes, no, that…

FG1F2: Many of them are used to these “phone hotels” from junior high school, and then they come here and have access to it all the time, right.

FG1M1: Yes, yes.

FG1M2: When we made the class rules, we agreed that they should use flight mode during class.

FG1M3: Yes… but do they do it?

FG1M2: Yes. Always.

Most of them would probably trade a ‘like’ for a hug if they could. And that is a bit, like… Yes, I find it strange that they prioritize spending their time striving to be perfect on a screen rather than caring about how they are really doing in their lives. I think that’s a bit scary. (FG2M2)

Because they don’t have a clue themselves. Nor have they taken the time to get acquainted with it [social media]. And then they are not able to assess the dangers and… whether it is actually good for the child or not. So… I feel that the parents who don’t keep up, they have to pull themselves together and start paying attention. (FG2M2)

What I fear about social media is that they are lacking role models. Teachers. They learn from each other. And we don’t know what they teach each other. Do you know what I mean? (FG2M1)

Everything is filtered through [social media], and it comes out in a form that I don’t know very well. It is a completely different language than what we find in the literature, for example. (FG1F1)

They need to be a little more critical of what they see and what it does to their own emotions, and become more aware that what they see and the impressions they get can affect them. Either in a positive or in a negative way. We must teach adolescents to become a little more robust, that is, aware of the impressions they get and how it affects the choices they make and what they do with their lives. (FG2F1)

4. Discussion

4.1. A Vocal Concern for the Negative Effects of Social Media

4.2. Standing on the Outside

4.3. Social Media Can Be a Positive Social Arena

4.4. Implications

4.5. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, M.; Jiang, J. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Pew Research Center. 2018. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Smahel, D.; MacHackova, H.; Mascheroni, G.; Dedkova, L.; Staksrud, E.; Olafsson, K.; Livingstone, S.; Hasebrink, U. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey Results From 19 Countries. Science LSoEaP. 2020. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103294/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Bakken, A. Ungdata 2020: Nasjonale Resultater. NOVA. 2020. Available online: http://www.hioa.no/Om-OsloMet/Senter-for-velferds-og-arbeidslivsforskning/NOVA/Publikasjonar/Rapporter/Ungdata-2020 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Patalay, P.; Gage, S.H. Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: A population cohort comparison study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1650–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrebny, T.; Wiium, N.; Haugstvedt, A.; Sollesnes, R.; Torsheim, T.; Wold, B.; Thuen, F. Health complaints among adolescents in Norway: A twenty-year perspective on trends. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Media use is linked to lower psychological well-being: Evidence from three datasets. Psychiatr. Q. 2019, 90, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Bishop, D.V.; Przybylski, A.K. The debate over digital technology and young people. BMJ 2015, 351, h3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Criddle, C. Social Media Damages Teenagers’ Mental Health, Report Says. BBC, 27 January 2021. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-55826238 (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Booth, R. Anxiety on Rise among the Young in Social Media Age. The Guardian, 5 February 2019. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/feb/05/youth-unhappiness-uk-doubles-in-past-10-years (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Brunborg, G.S.; Andreas, J.B. Increase in time spent on social media is associated with modest increase in depression, conduct problems, and episodic heavy drinking. J. Adolesc. 2019, 74, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, H.C.; Scott, H. # Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Birkjær, M.; Kaats, M. Does Social Media Really Pose a Threat to Young People’s Well-Being? 2019. Available online: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/does-social-media-really-pose-threat-young-peoples-well-being-0 (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Orben, A.; Przybylski, A.K. The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orben, A. Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schønning, V.; Hjetland, G.J.; Aarø, L.E.; Skogen, J.C. Social Media Use and Mental Health and Well-Being Among Adolescents–A Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.T.; Sidoti, C.L.; Briggs, S.M.; Reiter, S.R.; Lindsey, R.A. Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. J. Adolesc. 2017, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.L.; Algoe, S.B.; Green, M.C. Social network sites and well-being: The role of social connection. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malterud, K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001, 358, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M. Social media and adolescent mental health: The good, the bad and the ugly. J. Ment. Health 2020, 29, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throuvala, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D.; Rennoldson, M.; Kuss, D.J. Motivational processes and dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use among adolescents: A qualitative focus group study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, E. The social media see-saw: Positive and negative influences on adolescents’ affective well-being. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 3597–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, L.S.; Kolbe, L.; Lee, A.; McCall, D.S.; Young, I.M. School health promotion. In Global Perspectives on Health Promotion Effectiveness; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Skogen, J.C.; Smith, O.R.; Aarø, L.E.; Siqveland, J.; Øverland, S. Barn og Unges Psykiske Helse: Forebyggende og Helsefremmende Folkehelsetiltak. En Kunnskapsoversikt [Mental Health among Children and Adolescents. Health-Promoting and Preventive Public Health Interventions. A Summary of Evidence About Effects.]. 2018. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/rapporter/2018/barn_og_unges_psykiske_helse_forebyggende.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malterud, K. Fokusgrupper som Forskningsmetode for Medisin og Helsefag [Focus Groups as Research Method for Medicine and Health Sciences]; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjetland, G.J.; Schønning, V.; Hella, R.T.; Veseth, M.; Skogen, J.C. How do Norwegian adolescents experience the role of social media in relation to mental health and well-being: A qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, J.C.; Hjetland, G.J.; Bøe, T.; Hella, R.T.; Knudsen, A.K. Through the Looking Glass of Social Media. Focus on Self-Presentation and Association with Mental Health and Quality of Life. A Cross-Sectional Survey-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2021, 18, 3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.A.; Steiner, G.Z.; Smith, L.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Gleeson, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Armitage, C.J.; et al. The “online brain”: How the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barlett, C.P.; Vowels, C.L.; Saucier, D.A. Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 27, 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H. How do “body perfect” ideals in the media have a negative impact on body image and behaviors? Factors and processes related to self and identity. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, S.; Ward, L.M.; Hyde, J.S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsen, I.; Kraft, P.; Røysamb, E. The relationship between body image and depressed mood in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal panel study. J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Dogra, N.; Whiteman, N.; Hughes, J.; Eruyar, S.; Reilly, P. Is social media bad for mental health and wellbeing? Exploring the perspectives of adolescents. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Bosworth, K.; Simon, T.R. Examining the social context of bullying behaviors in early adolescence. J. Couns. Dev. 2000, 78, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, S.; Hoff, D.L. Cyber bullying: Clarifying legal boundaries for school supervision in cyberspace. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2007, 7, 76–118. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, J.; Gross, E.F. Extending the school grounds?—Bullying experiences in cyberspace. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manago, A.M.; Graham, M.B.; Greenfield, P.M.; Salimkhan, G. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H.; Goldman, B.M. Authenticity, social motivation, and psychological adjustment. In Social Motivation: Conscious and Unconscious Processes; Forgas, J.P., Williams, K.D., Laham, S.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 210–227. [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke, L.; Trepte, S. Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, A.L.; Wood, J.V. When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, K.; Rainie, L.; Heaps, A.; Buchanan, J.; Friedrich, L.; Jacklin, A.; Chen, C.; Zickuhr, K. How Teens do Research in the Digital World. 2012. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537513.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Demirbilek, M.; Talan, T. The effect of social media multitasking on classroom performance. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.S.; Pody, B.C.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; McDonough, I.M. The effect of cellphones on attention and learning: The influences of time, distraction, and nomophobia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.L.S.; Valença, A.M.; Silva, A.C.; Sancassiani, F.; Machado, S.; Nardi, A.E. “Nomophobia”: Impact of cell phone use interfering with symptoms and emotions of individuals with panic disorder compared with a control group. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2014, 10, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. Horizon 2001, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Czerniewicz, L. Debunking the ‘digital native’: Beyond digital apartheid, towards digital democracy. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2010, 26, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Bukowski, W.M.; Parker, J.G. Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In Handbook of Child Psychology, 3rd ed.; Eisenberg, N., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Medietilsynet: Om Sosiale Medier Og Skadelig Innhold På Nett. 2020. Available online: https://medietilsynet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/barn-og-medier-undersokelser/2020/200211-barn-og-medier-2020-delrapport-1_-februar.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- McKenna, K.Y.; Green, A.S.; Gleason, M.E. Relationship formation on the Internet: What’s the big attraction? J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfield, C.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core Corriculum: Health and Life Skills. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. Available online: https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/prinsipper-for-laring-utvikling-og-danning/tverrfaglige-temaer/folkehelse-og-livsmestring/?lang=eng (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- O’Keeffe, G.S.; Clarke-Pearson, K. The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mueller, M. Challenging the Social Media Moral Panic: Preserving Free Expression under Hypertransparency. Cato Institute. 2019. Available online: https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/challenging-social-media-moral-panic-preserving-free-expression-under (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Eidem, M.; Overå, S. Gaming og Skjermbruk i et Familieperspektiv. Forebygging.no 2020. Available online: https://www.forebygging.no/Artikler/2020/Gaming-og-skjermbruk-i-et-familieperspektiv (accessed on 11 December 2020). [CrossRef]

| Participant ID | Focus Group Interview Number | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| FG1M1 | 1 | Male |

| FG1M2 | 1 | Male |

| FG1M3 | 1 | Male |

| FG1F1 | 1 | Female |

| FG1F2 | 1 | Female |

| FG2M1 | 2 | Male |

| FG2M2 | 2 | Male |

| FG2F1 | 2 | Female |

| FG2F2 | 2 | Female |

| FG2M3 | 2 | Male |

| FG2M4 | 2 | Male |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hjetland, G.J.; Schønning, V.; Aasan, B.E.V.; Hella, R.T.; Skogen, J.C. Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179163

Hjetland GJ, Schønning V, Aasan BEV, Hella RT, Skogen JC. Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179163

Chicago/Turabian StyleHjetland, Gunnhild Johnsen, Viktor Schønning, Bodil Elisabeth Valstad Aasan, Randi Træland Hella, and Jens Christoffer Skogen. 2021. "Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179163

APA StyleHjetland, G. J., Schønning, V., Aasan, B. E. V., Hella, R. T., & Skogen, J. C. (2021). Pupils’ Use of Social Media and Its Relation to Mental Health from a School Personnel Perspective: A Preliminary Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179163