HIV–AIDS Stigma in Burundi: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. AIDS in Burundi

1.2. The Problem of HIV-Related Stigma in Burundi

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conducting Interviews

2.2. Testimonial Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. HIV Stigma Dimensions Experienced by PLWHA in Burundi

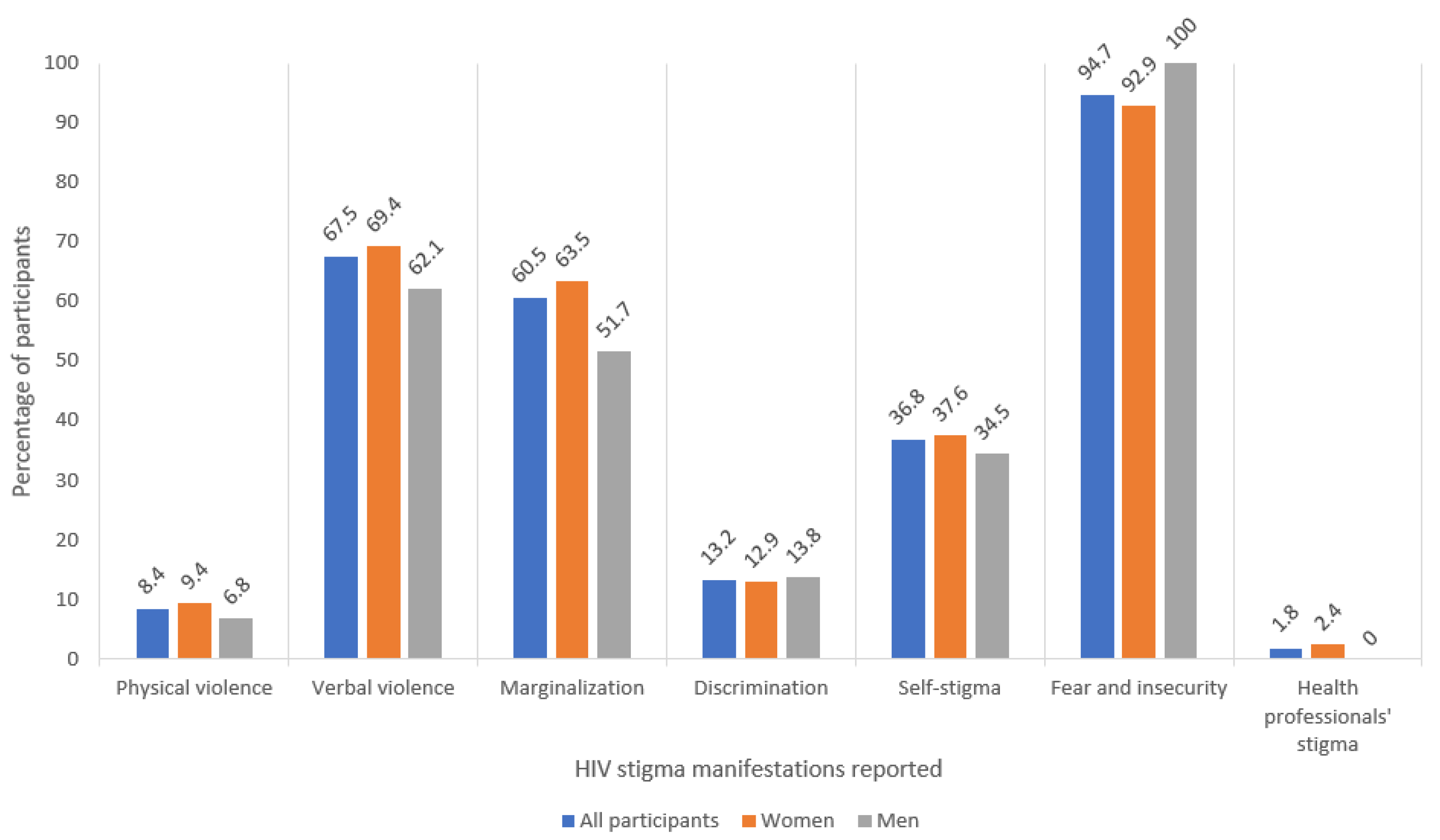

3.2. Extent of the Different Manifestations of Stigma in PLWHA in Burundi

3.3. Characterization of HIV Stigma Experienced by PLWHA in Burundi

3.3.1. Physical Violence

3.3.2. Verbal Violence

3.3.3. Marginalization

3.3.4. Discrimination

3.3.5. Self-Stigma

3.3.6. Fear and Insecurity

3.3.7. Health Professionals’ Stigma

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministere de la santé Publique et de la lutte Contre le SIDA [Burundi] (MSPLS); Conseil National de Lutte Contre le SIDA [Burundi] (CNLS). Plan Estratégique National de Lutte Contre le SIDA 2012–2016; MSPLS; CNLS: Burundi, 2012. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_202048.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Ministère à la présidence Chargé de la Bonne Gouvernance et du Plan [Burundi] (MPBGP); Ministère de la santé Publique et de la lutte Contre le SIDA [Burundi] (MSPLS); Institut de Statistiques et d’études économiques du Burundi (ISTEEBU); et ICF. Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Burundi 2016–2017: Rapport de Synthèse; ISTEEBU; MSPLS; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018; Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR247/SR247.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Programme Commun des Nations Unies sur le VIH/sida (ONUSIDA); Conseil National de Lutte Contre le SIDA [Burundi] (CNLS). Rapport d’activités sur la lutte Contre le SIDA et le Rapport sur les Progres Enrogistrés vers l’accès Universal (Burundi); ONUSIDA; CNLS: Burundi, 2015; Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/BDI_narrative_report_2015.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016–2021. Towards Ending AIDS; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246178 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Mbonu, N.C.; van den Borne, B.; De Vries, N.K. Stigma of People with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Literature Review. J. Trop. Med. 2009, 2009, 145891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Smith, L.R.; Chaudoir, S.R.; Amico, K.R.; Copenhaver, M.M. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mak, W.W.S.; Poon, C.Y.M.; Pun, L.Y.K.; Cheung, S.F. Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J. HIV disease progression: Depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leserman, J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosomaic Med. 2008, 70, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Capron, D.W.; Gonzalez, A.; Parent, J.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Schmidt, N.B. Suicidality and anxiety sensitivity in adults with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012, 26, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrico, A.W. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: Implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, A.; Chopra, M.; Kadiyala, S. Factors related to HIV disclosure in 2 South African communities. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A.C.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Kegeles, S.M.; Katz, I.T.; Haberer, J.E.; Muzoora, C.; Kumbakumba, E.; Hunt, P.W.; Martin, J.N.; Weiser, S.D. Internalized stigma, social distance, and disclosure of HIV seropositivity in rural Uganda. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Emlet, C.A. A comparison of HIV stigma and disclosure patterns between older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2006, 20, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sayles, J.N.; Wong, M.D.; Kinsler, J.J.; Martins, D.; Cunningham, W.E. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). HIV Testing, Treatment and Prevention. Generic Tools for Operational Research; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/operational/or_generic_tools.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Reduction of HIV-Related Stigma and Discrimination. UNAIDS: Geneva, 2014. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2014unaidsguidancenote_stigma_en.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Rao, D.; Elshafei, A.; Nguyen, M.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Frey, S.; Go, V.F. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: State of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Brakel, W.H.; Cataldo, J.; Grover, S.; Kohrt, B.A.; Nyblade, L.; Stockton, M.; Wouters, E.; Yang, L.H. Out of the silos: Identifying cross-cutting features of health-related stigma to advance measurement and intervention. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heijnders, M.; Van Der Meij, S. The fight against stigma: An overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, G.Z.; Reinius, M.; Eriksson, L.E.; Svedhem, V.; Esfahani, F.M.; Deuba, K.; Rao, D.; Lyatuu, G.W.; Giovenco, D.; Ekström, A.M. Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e129–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartog, K.; Hubbard, C.D.; Krouwer, A.F.; Thornicroft, G.; Kohrt, B.A.; Jordans, M. Stigma reduction interventions for children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of intervention strategies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 246, 112749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris France, N.; Macdonald, S.H.; Conroy, R.R.; Chiroro, P.; Ni Cheallaigh, D.; Nyamucheta, M.; Mapanda, B.; Shumba, G.; Mudede, D.; Byrne, E. ‘We are the change’-An innovative community-based response to address self-stigma: A pilot study focusing on people living with HIV in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.W.; Lemos, D.; Hosek, S.G. Stigma reduction in adolescents and young adults newly diagnosed with HIV: Findings from the Project ACCEPT intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014, 28, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flickinger, T.E.; DeBolt, C.; Xie, A.; Kosmacki, A.; Grabowski, M.; Waldman, A.L.; Reynolds, G.; Conaway, M.; Cohn, W.F.; Ingersoll, K.; et al. Addressing Stigma Through a Virtual Community for People Living with HIV: A Mixed Methods Study of the PositiveLinks Mobile Health Intervention. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3395–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, P.H.X.; Chan, Z.C.Y.; Loke, A.Y. Self-Stigma Reduction Interventions for People Living with HIV/AIDS and Their Families: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 707–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.K.; Xu, R.H.; Hunt, S.L.; Wei, C.; Tucker, J.D.; Tang, W.; Luo, D.; Xue, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; et al. Combating HIV stigma in low- and middle-income healthcare settings: A scoping review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, G.T.; Lockwood, C.; Woldie, M.; Munn, Z. Reducing HIV-related stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings: A systematic review of quantitative evidence. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Derose, K.P.; Griffin, B.A.; Kanouse, D.E.; Bogart, L.M.; Williams, M.V.; Haas, A.C.; Flórez, K.R.; Collins, D.O.; Hawes-Dawson, J.; Mata, M.A.; et al. Effects of a Pilot Church-Based Intervention to Reduce HIV Stigma and Promote HIV Testing Among African Americans and Latinos. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 1692–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsai, A.C.; Hatcher, A.M.; Bukusi, E.A.; Weke, E.; Lemus Hufstedler, L.; Dworkin, S.L.; Kodish, S.; Cohen, C.R.; Weiser, S.D. A Livelihood Intervention to Reduce the Stigma of HIV in Rural Kenya: Longitudinal Qualitative Study. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babalola, S.; Fatusi, A.; Anyanti, J. Media saturation, communication exposure and HIV stigma in Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodajo, B.S.; Thupayagale-Tshweneagae, G.; Akpor, O.A. Stigma and discrimination within the Ethiopian health care settings: Views of inpatients living with human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2017, 9, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuteesa, M.O.; Wright, S.; Seeley, J.; Mugisha, J.; Kinyanda, E.; Kakembo, F.; Mwesigwa, R.; Scholten, F. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among HIV-positive older persons in Uganda—A mixed methods analysis. SAHARA J J. Soc. Asp. HIV AIDS Res. Alliance 2014, 11, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.T.; Weiser, S.D.; Boum, Y.; Siedner, M.J.; Mocello, A.R.; Haberer, J.E.; Hunt, P.W.; Martin, J.N.; Mayer, K.H.; Bangsberg, D.R.; et al. Persistent HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda during a period of increasing HIV incidence despite treatment expansion. AIDS 2015, 29, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, B.T.; Tsai, A.C. HIV stigma trends in the general population during antiretroviral treatment expansion: Analysis of 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 2003–2013. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 72, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burundi: Loi n° 1/018 du 12 mai 2005 Portant Protection Juridique des Personnes Infectées par le virus de l’immunodéficience Humaine et des Personnes Atteintes du Syndrome de l’immunodéficience Acquise. Burundi. 2005. Available online: https://toolkit.hivjusticeworldwide.org/fr/resource/loi-n-1018-du-12-mai-2005-portant-protection-juridique-des-personnes-infectees-par-le-virus-de-limmunodeficience-humaine-et-des-personnes-atteintes-du-syndrome-de-l/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- France, N.F.; Macdonald, S.H.; Conroy, R.R.; Byrne, E.; Mallouris, C.; Hodgson, I.; Larkan, F. ‘An unspoken world of unspoken things’: A study identifying and exploring core beliefs underlying self-stigma among people living with HIV and AIDS in Ireland. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 2015, 145, w14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku, K.A.; Linn, J.G.; Fife, B.L.; Azar, S.; Kendrick, L. A comparative analysis of perceived stigma among HIV-positive Ghanaian and African American males. SAHARA-J J. Soc. Asp. HIV AIDS Res. Alliance 2005, 2, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Colmenero, T.; Pérez-Morente, M.Á.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Capilla-Díaz, C.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Hueso-Montoro, C. Experiences and Attitudes of People with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neuman, M.; Obermeyer, C.M.; MATCH Study Group. Experiences of stigma, discrimination, care and support among people living with HIV: A four country study. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 1796–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Chaudoir, S.R. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcesepe, A.; Tymejczyk, O.; Remien, R.; Gadisa, T.; Kulkarni, S.G.; Hoffman, S.; Melaku, Z.; Elul, B.; Nash, D. HIV-Related Stigma, Social Support, and Psychological Distress Among Individuals Initiating ART in Ethiopia. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3815–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, L.A.; Rueda, S.; Baker, D.N.; Wilson, M.G.; Deutsch, R.; Raeifar, E.; Rourke, S.B.; Stigma Review Team. Stigma, HIV and health: A qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, E.B.; Ferrans, E.C.; Lashley, R.F. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res. Nurs. Health 2001, 24, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Main Dimensions of HIV Stigma | Reference Where the Categorization Appears |

|---|---|

| Social rejection, financial insecurity, internalized shame, and social interaction. | [39] |

| Social stigma (prejudice which, in many cases, results in the social exclusion of PLWHA), self-stigma (feelings of guilt and embarrassment, of being useless, not respectable, and undesirable to other people), and health professionals’ stigma (related to the attitudes of these professionals towards PLWHA). | [40] |

| Interpersonal discrimination (verbal or physical abuse, exclusion, and loss of employment or housing), discrimination in healthcare facilities, and internalized stigma (feeling worthless or guilty about HIV status). | [41] |

| Enacted stigma or stigmatizing attitudes (prejudice and discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHA), anticipated or anticipatory stigma (expectation of PLWHA that they will experience prejudice and discrimination from others in the future), and internalized stigma (negative feelings of PLWHA about themselves on the basis of suffering from HIV/AIDS). | [6,34,42,43] |

| Enacted stigma (discriminatory behaviors from others), felt stigma (internalization of stigma), marginalization (other forms of social devaluation), disclosure (disclosure of HIV status), morals and values, and visible health (visible symptoms of AIDS status). | [44] |

| Personalized stigma (consequences that plwha perceives of other people knowing that they have HIV), disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and concern with public attitudes toward PLWHA. | [45] |

| Fear of casual transmission and refusal of contact, negative judgments about people living with hiv, internalized stigma or self-stigma, enacted stigma (including violence, marginalization, and discrimination), discrimination in institutional settings, discriminatory laws and policies, and compounded or ‘layered’ stigma (‘HIV-related stigma that mutually reinforces and legitimates pre-existing stigma and discrimination against marginalized groups such as sex workers, injecting drug users or men who have sex with men’). | [16] |

| 1. Physical Violence |

|---|

| 2. Verbal Violence 2.1. Unpleasant words, insults 2.2. Accusations 2.3. Gossip, criticism of the PLWHA behind their back |

| 3. Marginalization 3.1. Rejection by spouse 3.2. Rejection and persecution by other family members 3.3. Refusal to share things with them and touch the same things (plates for food, closet for clothes) 3.4. SOCIAL isolation 3.5. abandonment in hospitals by their relatives 3.6. Distancing by neighbors 3.7. Banning of children from playing with those of hiv-positive parents |

| 4. Discrimination 4.1. Difficulty in getting a job 4.2. Difficulty in obtaining company loans at work 4.3. Eviction from rental houses by owners |

| 5. Self-Stigma 5.1. Shame 5.2. Guilt 5.3. Attempted suicide |

| 6. Fear and Insecurity 6.1. Fear of illness, fear of dying soon 6.2. Fear that their HIV status will be discovered |

| 7. Health Professionals’ Stigma |

| Hiv Stigma Dimensions and Manifestations | Total No. of Participants Who Report Having Experienced Manifestation of the Stigma (%) | Total No. of Women Who Report Having Experienced Manifestation of the Stigma (%) | Total No. of Men Who Report Having Experienced Manifestation of the Stigma (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Physical Violence | 8.8 | 9.4 | 6.8 |

| 2. Verbal Violence 2.1. Unpleasant words, insults 2.2. Accusations 2.3. Gossip, criticism of the plwha behind their back | 67.5 33.3 14 50.9 | 69.4 32.9 12.9 52.9 | 62.1 34.5 17.2 44.8 |

| 3. Marginalization 3.1. Rejection by spouse 3.2. Rejection and persecution by other family members 3.3. Refusal to share things with them and touch the same things (plates for food, closet for clothes) 3.4. Social isolation 3.5. Abandonment in hospitals by their relatives 3.6. Distancing by neighbors 3.7. Banning of children from playing with those of hiv-positive parents | 60.5 12.3 18.4 14.9 11.4 1.8 25.4 6.1 | 63.5 14.1 21.2 16.5 11.8 2.4 24.7 5.9 | 51.7 6.9 10.3 10.3 10.3 0 27.6 6.9 |

| 4. Discrimination 4.1. Difficulty in getting a job 4.2. Difficulty in obtaining company loans at work 4.3. Eviction from rental houses by owners | 13.2 3.5 5.3 6.1 | 12.9 2.4 4.7 7.1 | 13.8 6.9 6.9 3.5 |

| 5. Self-Stigma 5.1. Shame 5.2. Guilt 5.3. Suicide attempt | 36.8 25.4 17.5 2.6 | 37.6 29.4 15.3 2.4 | 34.5 13.8 24.1 3.4 |

| 6. Fear and insecurity 6.1. Fear of illness, fear of dying soon 6.2. Fear that their hiv status will be discovered | 94.7 50 89.5 | 92.9 50.6 89.3 | 100 48.3 86.2 |

| 7. Health Professionals’ Stigma | 1.8 | 2.4 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Njejimana, N.; Gómez-Tatay, L.; Hernández-Andreu, J.M. HIV–AIDS Stigma in Burundi: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179300

Njejimana N, Gómez-Tatay L, Hernández-Andreu JM. HIV–AIDS Stigma in Burundi: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179300

Chicago/Turabian StyleNjejimana, Néstor, Lucía Gómez-Tatay, and José Miguel Hernández-Andreu. 2021. "HIV–AIDS Stigma in Burundi: A Qualitative Descriptive Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9300. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179300