Process of Posthospital Care Involving Telemedicine Solutions for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- 389,642 THA (63.09% of all joint replacement)—in Poland;

- 625,097 THA (33.3% of all joint replacement)—in USA.

- In total, in 91% of cases result from primary bilateral coxarthrosis (M16.0), femoral neck fracture (S72.0) or other primary coxarthrosis (M16.1);

- In total, arthroplasty occurs in 87% of cases;

- Women represent over 57% of implants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Process Diagram

2.2. Literature Search

- (A) What is the process of post-hospital care for patients after THA in Poland and in the world? (B) What telemedicine technologies are used in post-hospital care?

- How does the use of telemedicine technologies affect the effectiveness of post-hospital care for patients after THA?

- What is the opinion of patients and staff about telemedicine technologies used in post-hospital care after THA?

2.3. Data Collection Methods in Our Empirical Research

2.3.1. Participant Observation

2.3.2. Structured Interviews

- to determine the general stages of posthospital care in everyday clinical practice in a Polish hospital specializing in THA and providing outpatient specialist care in the field of trauma and orthopedic surgery;

- to define knowledge on example telemedicine tools possible to be used in patient care processes;

- to define causes and consequences of possible postoperative complications;

- to define disadvantages of the current posthospital care process.

2.3.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Previous Attempts to Develop a More Modern Version of Patient Care Process after Hip Arthroplasty

2.4.1. Analysis of Posthospital Care Recommended by AOTMiT in the Report on Comprehensive Patient Care in Hip Arthroplasty

2.4.2. Characteristics of Telerehabilitation before and after Hip and Knee Arthroplasty within CLEAR Project

- The patient uses at home videos with exercises selected for him by the therapist;

- The patient uses the phone application with exercises selected for him by the therapist;

- The therapist tracks the patient’s exercises on an ongoing basis through video consultation;

- The therapist follows the patient’s exercise performance on an ongoing basis via the internet platform.

- Patients with neurological diseases—research team from Spain;

- Patients with lung diseases and chronic pain—a research team in the Netherlands;

- Patients after a stroke—a research team in Italy;

- Patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee joints—research team in Poland.

2.5. Characteristics of Hybrid Cardiac Telerehabilitation

- An initial visit to the doctor: examination, ECG and exercise test or an ergospirometry test or a six-minute walk test, planning training loads, including the range of the training heart rate and qualification for the appropriate model of HCTR;

- Five days of visits to the outpatient clinic (two to three h each): educational meetings, learning how to use telerehabilitation equipment, learning exercises, dietician’s consultation, psychologist’s consultation, training sessions and lectures on the validity of rehabilitation and a healthy lifestyle.

- Between 20 and 24 training sessions (40–60 min each) at home or at the patient’s current location;

- Two procedures repeated daily: permission to start the exercise and training session. Each session is preceded by a phone contact of the patient with the telemonitoring center and data transmission, i.a., resting ECG, blood pressure and body weight measurement. After analyzing the monitoring center, in the absence of contraindications, the patient begins a training session. During each session, telemedicine supervision over the patient is carried out and after the end of the training session, the physiotherapist calls the patient by phone to discuss the course of exercises and determine the degree of effort load;

- A final medical visit to the outpatient clinic: examination, exercise or ergospirometry test or six-minute walk test, evaluation of the effectiveness and summary of the hybrid telerehabilitation cycle and further recommendations.

3. Results

3.1. Design Guidelines

3.1.1. Answers to Research Questions

- (A) What is the process of post-hospital care for patients after THA in Poland and in the world? (B) What telemedicine technologies are used in post-hospital care?

- Personal follow-up visits to the orthopedist should take place 6 weeks and 1 year after the procedure, then every 2 years [33].

- Personal follow-up visits should take place at least in the first year after surgery, 5 years after surgery or earlier if the orthopedic surgeon considers as necessary [34].

- It is vital to make the patient aware of the importance of personal follow-up visits in the postoperative period. The issue of the frequency of follow-up visits in the postoperative period requires standardization. Clinics schedule 3 control visits in the first year after surgery, at least 3 control visits in the next 10 years and then annual control visits [35].

- First period—immediately after the surgery—including standing upright in the hospital ward, in the absence of complications the patient stays in the hospital ward few days, up to a week;

- Second period—from the end of the week 1 to the beginning of the week 5—including walking on crutches or a walking frame with the relief of the operated limb;

- Third period—from 5 to 12 weeks—including exercises of all muscle groups and improvement of self-service and gradual increase in training load after 4–6 weeks.

- 2.

- How does the use of telemedicine technologies affect the effectiveness of post-hospital care for patients after THA?

- 3.

- What is the opinion of patients and staff about telemedicine technologies used in post-hospital care after THA?

3.1.2. Design Guidelines from Participant Observation

- Types of rehabilitation in posthospital patient care process:

- ambulatory rehabilitation—stationary;

- ambulatory rehabilitation—at patient home;

- rehabilitation ward, recommended depending on the patient’s health condition;

- Physiotherapists’ instructions directed to patient in hospital in the field of self-rehabilitation at home in posthospital period:

- oral instructions;

- presentation of exercise/body and limb movement performance, written instructions (printed instruction with text descriptions and graphic visualization of exercises) given during patients stay at the hospital after THA;

- Patient registration process for control visits in posthospital period:

- patients register control visits at outpatient specialist care on the referral received upon discharge from hospital;

- all information in regard to dates and intervals between visits are given at outpatient specialist care by reception personnel;

- comprehensive patient care after THA is possible in medical facility offering access to services needed in posthospital patient care (patient can register for control visit at the same day of discharge from hospital at the medical facility);

- Observation on video consultation tool implemented as commercial service for patients:

- The orthopedist efficiently uses the video-consultations tool without administration assistance;

- the video consultation system includes the possibility of electronic medical records storage;

- the orthopedist using the telemedicine tool has a work schedule previously set up in the telemedicine system;

- the orthopedist cooperates with administration personnel and shares opinions on the functioning of telemedicine system resulting from his experience after video consultation is conducted.

3.1.3. Design Guidelines from Structured Interviews

- Control visits after THA:

- control visits are important for monitoring patient condition;

- there is no strict standardization of the frequency of control visits;

- number of control visits depends on patient condition;

- patients do not always attend control visits on the set dates;

- there is no role of coordinator provided in the structure of the posthospital care process who is the patient’s guardian, e.g., in regard to phone control visits reminders;

- Rehabilitation after THA:

- the type of rehabilitation depends on the patient’s health condition;

- instructed self-rehabilitation at home has an important impact on patient recovery;

- patients perform self-rehabilitation at home according to the given oral and written instructions with pictures;

- Common causes of medical complications after THA:

- lack of patient rehabilitation;

- patient collapse;

- failure to follow specialistic instructions (from orthopedist and physiotherapist) regarding temporarily prohibited patient’s body movements;

- Patient attitude after THA:

- patient can be stressed/unsure just after surgery in regard to proper body movement, activity and general functioning;

- patients are open to use orthopedic aids and devices facilitating their functioning;

- Telemedicine tools:

- there is no telemedicine tool (telerehabilitation programs, collapse wrist bands) widely known and/or used to supervise patients’ physical condition, activity and the correctness and frequency of exercise at home by the patient;

- hospital personnel have general knowledge on telemedicine solutions (e.g., hybrid cardiac telerehabilitation was mentioned as application example);

- patients are open to using collapse sensors if equipped.

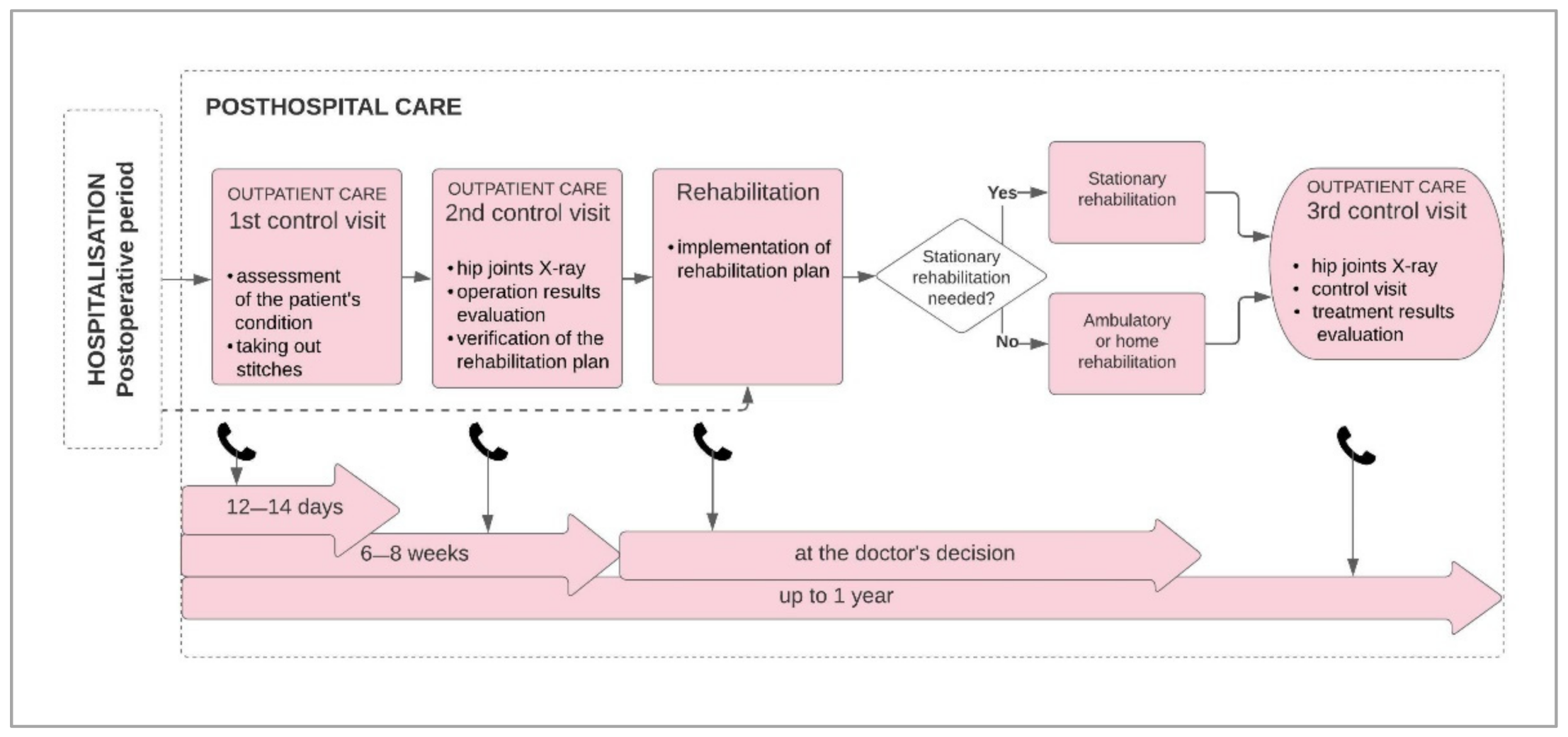

3.1.4. Diagram of Current Posthospital Patient Care Process after THA and Synthetic Conclusions for New Process Design

- First follow-up visit—takes place one week after the procedure to assess the patient’s general condition and control of the postoperative wound;

- Second follow-up visit—takes place after two weeks to assess the general condition of the patient and remove the stitches;

- Third follow-up visit—takes place after 6–8 weeks to assess the patient’s physical condition, verify the rehabilitation plan and, if necessary, take a control X-ray of the hip joints;

- Fourth, fifth and sixth follow-up visits—take place after 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively, to assess the patient’s physical condition, take a control X-ray of the hip joints, or in individually recommended periods depending on patient condition.

- There is a lack of tools for sufficient patient supervision during his stay at home, i.a., the lack of monitoring of the patient’s collapse, general physical activity in everyday life and realization of rehabilitation program after discharge from the hospital.

- There is a lack of comprehensive care model to ensure proper patient care after THA which is major surgery with risk of complications.

3.2. Project of Improved Posthospital Patient Care Process Using High Technologies—Final Results

- Physiotherapy;

- Outpatient specialist care;

- Telemonitoring.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Can increase the patient’s safety;

- Enables the conduction of rehabilitation remotely in the event of the lack of access to outpatient physiotherapy services or the lack of the patient transport to the rehabilitation center;

- It may contribute to shortening the convalescence time, reducing the risk of complications, as well as reducing treatment costs.

- Current process of post-hospital care process for patient after THA is not applying the full potential of available telemedicine technologies.

- High quality post-hospital care to maintain the intended effect of recovery is needed, increasing the number of costly THA procedures.

- The post-hospital period for patients undergoing THA is important, including the monitoring of fails that may be the cause of repeated need for surgery.

- This type of procedure minimizes personal interaction a contributing to limiting epidemiological threats development, for example, those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bokolo, A. Implications of telehealth and digital care solutions during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative literature review. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2021, 46, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernd, T.; Van Der Pijl, D.; De Witte, L.P. Existing models and instruments for the selection of assistive technology in rehabilitation practice. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 16, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hunter, D.J.; Vesentini, G.; Pozzobon, D.; Ferreira, M.L. Technology-assisted rehabilitation following total knee or hip replacement for people with osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 3, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamecka, K.; Engelseth, P.; Staszewska, A.; Kozlowski, R. Conditions for Implementing Innovating Telemedicine Procedures after Hip Arthroplasty. In Research and the Future of Telematics. TST 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Mikulski, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1289, pp. 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, M.A.; Russell, T.G. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci. Pract. 2020, 48, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.M.; Harjumaa, M.; Puhto, A.P.; Pikkarainen, M. Healthcare professionals’ proposed eHealth needs in elective primary fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty journey: A qualitative interview study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4434–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, R.; Seaman, K.; Ashford, C.; Sullivan, T.; McDowall, J.; Whitehead, L.; Ewens, B.; Pedler, K.; Gullick, K. An eHealth Program for Patients Undergoing a Total Hip Arthroplasty: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surgical Operations and Procedures Performed in Hospitals—Top 10 Procedures Group 2, 2018 (per 100,000 Inhabitants) Health20.png. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Surgical_operations_and_procedures_performed_in_hospitals_%E2%80%94_top_10_procedures_group_2,_2018_(per_100_000_inhabitants)_Health20.png (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- The American Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report. Available online: https://www.aaos.org/registries/publications/ajrr-annual-report/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Realizacja Świadczeń Endoprotezoplastyki Stawowej w 2019 r. na podstawie Danych z Centralnej Bazy Endoprotezoplastyk Narodowego Funduszu Zdrowia. Available online: https://www.nfz.gov.pl/o-nfz/publikacje/ (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Świtoń, A.; Wodka-Natkaniec, E.; Niedźwiedzki, Ł.; Gaździk, T.; Niedźwiedzki, T. Activity and Quality of Life after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białkowska, M.; Stołtny, T.; Pasek, J.; Mielnik, M.; Czech, S.; Ostałowska, A.; Kasperczyk, S.; Koczy, B. Quality of Life of Men after Cementless Hip Replacement—A Pilot Study. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Learmonth, I.D.; Young, C.; Rorabeck, C. The operation of the century: Total hip replacement. Lancet 2007, 27, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengler, A.; Nimptsch, U.; Mansky, T. Hip and knee replacement in Germany and the USA: Analysis of individual inpatient data from German and US hospitals for the years 2005 to 2011. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014, 111, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruzaman, H.; Kinghorn, P.; Oppong, R. Cost-effectiveness of surgical interventions for the management of osteoarthritis: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kheir, M.; Rondon, A.J.; Bonaddio, V.; Tan, T.L.; Wang, C.; Purtill, J.J.; Courtney, P.M. Perioperative Telephone Encounters Should Be Included in the Relative Value Scale Update Committee Review of Time Spent on Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.E.; Codazza, S.; Ferriero, G.; Ricciardi, D.; Foti, C.; Maccauro, G.; Ronconi, G. The effectiveness of telerehabilitation after hip or knee arthroplasty: A narrative review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- El Ashmawy, A.H.; Dowson, K.; El-Bakoury, A.; Hosny, H.A.H.; Yarlagadda, R.; Keenan, J. Effectiveness, Patient Satisfaction, and Cost Reduction of Virtual Joint Replacement Clinic Follow-Up of Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 816–822.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Emara, A.K.; Ng, M.K.; Evans, P.J.; Estes, K.; Spindler, K.P.; Mroz, T.; Patterson, B.M.; Krebs, V.E.; Pinney, S.; et al. Transformation from a traditional model to a virtual model of care in orthopaedic surgery: COVID-19 experience and beyond. Bone Jt. Open 2020, 1, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endoprotezoplastyka Stawu Biodrowego—Opieka Kompleksowa. Available online: http://wwwold.aotm.gov.pl/assets/files/taryfikacja/raporty/SZP_biodro/AOTMiT_WT_553_14_2015_endoprotezoplastyka_kompleksowa_raport.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Poland: Country Health Profile 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/poland-country-health-profile-2019_297e4b92-en (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Final Results of the CLEAR Project. Available online: https://www.habiliseurope.com/clear-project/dissemination (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Piotrowicz, E. How to do: Telerehabilitation in heart failure patients. Cardiol. J. 2012, 19, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Zieliński, T.; Bodalski, R.; Rywik, T.; Dobraszkiewicz-Wasilewska, B.; Sobieszczańska-Małek, M.; Stepnowska, M.; Przybylski, A.; Browarek, A.; Szumowski, Ł.; et al. Home-based telemonitored Nordic walking training is well accepted, safe, effective and has high adherence among heart failure patients, including those with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: A randomised controlled study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 1, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, E.; Piotrowicz, R.; Opolski, G.; Pencina, M.; Banach, M.; Zaręba, W. Hybrid comprehensive telerehabilitation in heart failure patients (TELEREH-HF): A randomized, multicenter, prospective, open-label, parallel group controlled trial-Study design and description of the intervention. Am. Heart J. 2019, 217, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applying Telemedicine Technologies in a Novel Model of Organizing and Implementing Comprehensieve Cardiac Rehabilitation in Heart Failure Patients—TELEREH-HF Study. Available online: https://telereh-hf.ikard.pl/en/ (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Piotrowicz, E.; Pencina, M.J.; Opolski, G.; Zareba, W.; Banach, M.; Kowalik, I.; Orzechowski, P.; Szalewska, D.; Pluta, S.; Glówczynska, R.; et al. Effects of a 9-Week Hybrid Comprehensive Telerehabilitation Program on Long-term Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure: The Telerehabilitation in Heart Failure Patients (TELEREH-HF) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020, 1, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowski, P.; Piotrowicz, R.; Zareba, W.; Pencina, M.J.; Kowalik, I.; Komar, E.; Opolski, G.; Banach, M.; Glowczynska, R.; Szalewska, D.; et al. Antiarrhythmic effect of 9-week hybrid cardiac telerehabilitation—subanalysis of the TELEREHabilitation in Heart Failure patients—TELEREH-HF randomized clinical trial. EP Europace 2021, 23, euab116.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, E. The management of patients with chronic heart failure: The growing role of e-Health. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2017, 14, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, A.; Longo, U.G.; Candela, V.; Fioravanti, S.; Giannone, L.; Arcangeli, V.; Alciati, V.; Berton, C.; Facchinetti, G.; Marchetti, A.; et al. Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Gamification, and Telerehabilitation: Psychological Impact on Orthopedic Patients’ Rehabilitation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.; Seaman, K.; Emery, L.; Bulsara, M.; Ashford, C.; McDowall, J.; Gullick, K.; Ewens, B.; Sullivan, T.; Foskett, C.; et al. Comparing an eHealth Program (My Hip Journey) With Standard Care for Total Hip Arthroplasty: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2021, 8, e22944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Orthopaedic Association. Total Hip Joint Arthroplasty. Good Practice Guidelines. Available online: https://nzoa.org.nz/sites/default/files/Total_Hip_Joint_Arthroplasty_Guidelines_0.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Swierstra, B.A.; Vervest, A.; Walenkamp, G.; Schreurs, B.; Spierings, P.; Heyligers, I.; Susante, J.; Ettema, H.; Jansen, M.; Hennis, P.; et al. Dutch guideline on total hip prosthesis. Acta Orthop. 2011, 82, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hip & Knee Replacement Toolkit. Available online: http://boneandjointcanada.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/11-2821-RR_HipKnee_Replacement_Toolkit_V3.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Ridan, T.; Ogrodzka, K.; Klis, A. Postępowanie rehabilitacyjne po endoprotezoplastyce stawu biodrowego. Prakt. Fizjoter. Rehabil. 2013, 43, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Westby, M.D. Expert Consensus on Best Practices for Post–Acute Rehabilitation After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Canada and United States Delphi Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, E.N.; Sharma, A.K.; Gkiatas, I.; Elbuluk, A.M.; Sculco, P.K.; Vigdorchik, J.M. An Overview of Telehealth in Total Joint Arthroplasty. HSS J. 2021, 17, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, P.W.; Keller, R.A.; Mabee, K.A.; Pillai, R.; Frisch, N.B. Quantifying Patient Engagement in Total Joint Arthroplasty Using Digital Application-Based Technology. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 3108–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheper, H.; Derogee, R.; Mahdad, R.; van der Wal, R.J.P.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H.; Visser, L.G.; de Boer, M.G.J. A mobile app for postoperative wound care after arthroplasty: Ease of use and perceived usefulness. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 129, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebleu, J.; Poilvache, H.; Mahaudens, P.; De Ridder, R.; Detrembleur, C. Predicting physical activity recovery after hip and knee arthroplasty? A longitudinal cohort study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, W.; Karpinski, K.; Backhaus, L.; Bierke, S.; Häner, M. A systematic review about telemedicine in orthopedics. Arch Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharareh, B.; Schwarzkopf, R. Effectiveness of telemedical applications in postoperative follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 918–922.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, J.D.; Bryant, D.; MacDonald, S.J.; Naudie, D.D.; McCalden, R.W.; Howard, J.L. Feasibility, effectiveness and costs associated with a web-based follow-up assessment following total joint arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2014, 29, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, C.A.; Mont, M.A.; Backstein, D.J.; Browne, J.A.; Krebs, V.E.; Mason, J.B.; Taunton, M.J.; Callaghan, J.J. COVID Will End but Telemedicine May be Here to Stay. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 789–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chughtai, M.; Newman, J.M.; Sultan, A.A.; Khlopas, A.; Navarro, S.M.; Bhave, A.; Mont, M.A. The Role of Virtual Rehabilitation in Total Knee and Hip Arthroplasty. Surg. Technol. Int. 2018, 1, 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Dushaj, K.; Rasquinha, V.J.; Scuderi, G.R.; Hepinstall, M.S. Monitoring Surgical Incision Sites in Orthopedic Patients Using an Online Physician-Patient Messaging Platform. J Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 1897–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, F.; Turchetti, G. Telerehabilitation after total knee replacement in Italy: Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of a mixed telerehabilitation-standard rehabilitation programme compared with usual care. BMJ Open 2016, 17, e009964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Russell, T.; Crossley, K.; Bourke, M.; McPhail, S. Cost-effectiveness of telerehabilitation versus traditional care after total hip replacement: A trial-based economic evaluation. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, M.; Moffet, H.; Nadeau, S.; Mérette, C.; Boissy, P.; Corriveau, H.; Marquis, F.; Cabana, F.; Ranger, P.; Belzile, É.L.; et al. Cost analysis of in-home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Med. Internet Res. 2015, 31, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuether, J.; Moore, A.; Kahan, J.; Martucci, J.; Messina, T.; Perreault, R.; Sembler, R.; Tarutis, J.; Zazulak, B.; Rubin, L.E.; et al. Telerehabilitation for Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Patients: A Pilot Series with High Patient Satisfaction. HSS J. 2019, 15, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pastora-Bernal, J.M.; Martin-Valero, R.; Baron-Lopez, F.J.; Estebanez-Perez, M.J. Evidence of Benefit of Telerehabitation After Orthopedic Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutras, C.; Bitsaki, M.; Koutras, G.; Nikolaou, C.; Heep, H. Socioeconomic impact of e-Health services in major joint replacement: A scoping review. Technol. Health Care 2015, 23, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.A. Leveraging Early Discharge and Telehealth Technology to Safely Conserve Resources and Minimize Personal Contact During COVID-19 in an Arthroplasty Practice. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, S52–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harno, K.; Arajärvi, E.; Paavola, T.; Carlson, C.; Viikinkoski, P. Clinical effectiveness and cost analysis of patient referral by videoconferencing in orthopaedics. J. Telemed. Telecare 2001, 7, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanham, N.S.; Bockelman, K.J.; McCriskin, B.J. Telemedicine and orthopaedic surgery. JBJS Rev. 2020, 8, e20.00083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiman, S.; Schwabe, M.T.; Barrack, R.L.; Nunley, R.M.; Clohisy, J.C.; Lawrie, C.M. Telemedicine for patients undergoing arthroplasty: Access, ability, and preference. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.J.; Hume, E.; Troxel, A.B.; Reitz, C.; Norton, L.; Lacko, H.; McDonald, C.; Freeman, J.; Marcus, N.; Volpp, K.G.; et al. Effect of Remote Monitoring on Discharge to Home, Return to Activity, and Rehospitalization after Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2028328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesterby, M.S.; Pedersen, P.U.; Laursen, M.; Mikkelsen, S.; Larsen, J.; Søballe, K.; Jørgensen, L.B. Telemedicine support shortens length of stay after fast-track hip replacement. Acta Orthop. 2017, 88, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nikolian, V.C.; Williams, A.M.; Jacobs, B.N.; Kemp, M.T.; Wilson, J.K.; Mulholland, M.W.; Alam, H.B. Pilot study to evaluate the safety, feasibility, and financial implications of a postoperative telemedicine program. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.M.; Rantala, A.; Miettunen, J.; Puhto, A.P.; Pikkarainen, M. The effects and safety of telerehabilitation in patients with lower-limb joint replacement: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler, S.; Salzwedel, A.; Rabe, S.; Mueller, S.; Mayer, F.; Wochatz, M.; Hadzic, M.; John, M.; Wegscheider, K.; Völler, H. The Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation as a Supplement to Rehabilitation in Patients After Total Knee or Hip Replacement: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 7, e14236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horton, B.S.; Marland, J.D.; West, H.S.; Wylie, J.D. Transition to Telehealth Physical Therapy After Hip Arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Pilot Study with Retrospective Matched-Cohort Analysis. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 13, 2325967121997469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, D.; Berges, I.; Bermúdez, J.; Goñi, A.; Illarramendi, A. A Telerehabilitation System for the Selection, Evaluation and Remote Management of Therapies. Sensors 2018, 18, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cottrell, M.A.; Galea, O.A.; O’Leary, S.P. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 31, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Lee, R.L.; Hunter, S.; Chan, S.W. The effectiveness of internet-based telerehabilitation among patients after total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lee, R.L.T.; Hunter, S.; Chan, S.W. The effectiveness of internet-based telerehabilitation among patients after total joint arthroplasty: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 115, 103845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.; Loeb, A.E.; Amin, R.M.; Golladay, G.J.; Levin, A.S.; Thakkar, S.C. Establishing Telemedicine in an Academic Total Joint Arthroplasty Practice: Needs and Opportunities Highlighted by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arthroplast. Today 2020, 6, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambare, T.D.; Bozic, K.J. Preparing for an Era of Episode-Based Care in Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.Y.; Geng, N.M.; Sun, J.Y.; Ren, P.; Ji, Q.B.; Li, J.C.; Zhang, G.Q. Modern instant messaging platform for postoperative follow-up of patients after total joint arthroplasty may reduce re-admission rate. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 27, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, D.; Tousignant, M.; Leclerc, N.; Côté, A.; Levasseur, M.; Researchers, T.T. The patient’s perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3998–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffet, H.; Tousignant, M.; Nadeau, S.; Mérette, C.; Boissy, P.; Corriveau, H.; Marquis, F.; Cabana, F.; Belzile, E.L.; Ranger, P.; et al. Patient satisfaction with in-home telerehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Telemed. J. e-Health 2017, 23, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; Biehl, E.; Titmuss, M.P.; Schwartz, R.; Gantha, C.S. HSS@Home, Physical Therapist-Led Telehealth Care Navigation for Arthroplasty Patients: A Retrospective Case Series. HSS J. 2019, 15, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buvik, A.; Bugge, E.; Knutsen, G.; Småbrekke, A.; Wilsgaard, T. Quality of care for remote orthopaedic consultations using telemedicine: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LeBrun, D.G.; Malfer, C.; Wilson, M.; Carroll, K.M.; Wang, V.; Mayman, D.J.; Cross, M.B.; Alexiades, M.M.; Jerabek, S.A.; Cushner, F.D.; et al. Telemedicine in an Outpatient Arthroplasty Setting During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Early Lessons from New York City. HSS J. 2021, 17, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.; Bourke, M.; Crossley, K.; Russell, T. Telerehabilitation is non- inferior to usual care following total hip replacement—A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. Physiotherapy 2020, 107, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, M.; Bourke, M.; Crossley, K.; Russell, T. Telerehabilitation Versus Traditional Care Following Total Hip Replacement: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 2, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Buchalter, D.B.; Sicat, C.S.; Aggarwal, V.K.; Hepinstall, M.S.; Lajam, C.M.; Schwarzkopf, R.S.; Slover, J.D. Telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: Adult reconstructive surgery perspective. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, H.; Nadeem, S.; Mundi, R. How Satisfied Are Patients and Surgeons with Telemedicine in Orthopaedic Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021, 479, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalron, A.; Tawil, H.; Peleg-Shani, S.; Vatine, J.J. Effect of telerehabilitation on mobility in people after hip surgery: A pilot feasibility study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2018, 41, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wainwright, T.W. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) for Hip and Knee Replacement-Why and How It Should Be Implemented Following the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina 2021, 57, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrożek-Gąsiorowska, M. Świadczenia rehabilitacyjne finansowane przez Narodowy Fundusz Zdrowia w latach 2005–2014. Zdrowie Publ. Zarządzanie 2015, 13, 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Hällfors, E.; Saku, S.A.; Mäkinen, T.J.; Madanat, R.A. Consultation Phone Service for Patients with Total Joint Arthroplasty May Reduce Unnecessary Emergency Department Visits. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davidovitch, R.I.; Anoushiravani, A.A.; Feng, J.E.; Chen, K.K.; Karia, R.; Schwarzkopf, R.; Iorio, R. Home Health Services Are Not Required for Select Total Hip Arthroplasty Candidates: Assessment and Supplementation with an Electronic Recovery Application. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, S49–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, K.J.; McGee-Lennon, M.R. Advances in telecare over the past 10 years. Smart Homecare Technol. TeleHealth 2013, 1, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomita, M.R.; Russ, L.S.; Sridhar, R.; Naughton, B.J. Chapter 8: Smart home with healthcare technologies for community—Dwelling older adults. In Smart Home Systems; Al-Qutayr, M.A., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2010; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parkes, R.J.; Palmer, J.; Wingham, J.; Williams, D.H. Is virtual clinic follow-up of hip and knee joint replacement acceptable to patients and clinicians? A sequential mixed methods evaluation. BMJ Open Qual. 2019, 1, e000502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Aspect of Interest/Subject of Observation | Observed Occupational Group | Number of Participant Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Types of rehabilitation in posthospital patient care process. | orthopedist, physiotherapist, nurse | 4 |

| Physiotherapists instructions directed to patient in hospital in the field of self-rehabilitation at home in posthospital period. | physiotherapist | 4 |

| Patient registration process for control visits in posthospital period. | reception personnel | 4 |

| Observation on video-consultation tool implemented as commercial service for patients. | orthopedist, administration personnel | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamecka, K.; Rybarczyk-Szwajkowska, A.; Staszewska, A.; Engelseth, P.; Kozlowski, R. Process of Posthospital Care Involving Telemedicine Solutions for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910135

Kamecka K, Rybarczyk-Szwajkowska A, Staszewska A, Engelseth P, Kozlowski R. Process of Posthospital Care Involving Telemedicine Solutions for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910135

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamecka, Karolina, Anna Rybarczyk-Szwajkowska, Anna Staszewska, Per Engelseth, and Remigiusz Kozlowski. 2021. "Process of Posthospital Care Involving Telemedicine Solutions for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910135

APA StyleKamecka, K., Rybarczyk-Szwajkowska, A., Staszewska, A., Engelseth, P., & Kozlowski, R. (2021). Process of Posthospital Care Involving Telemedicine Solutions for Patients after Total Hip Arthroplasty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910135