Australian Mental Health Consumers’ Experiences of Service Engagement and Disengagement: A Descriptive Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Why do consumers access particular mental health services over others?

- (2)

- Why do consumers disengage from mental health services?

- (3)

- What are the most common services with which consumers re-engaged?

2. Materials and Methods

- Eight were preliminary questions seeking demographic information (e.g., age, gender, location);

- The main section of the survey involved 18 questions, which asked the type of services accessed in the last five years, then sought Likert-rated or yes/no responses to questions asking about services used and why, access to services, perceived quality of services and health professionals, disengagement and why, and re-engagement and with whom. Each of these questions provided the opportunity for respondents to make further qualitative comments;

- The main section also involved 5 qualitative questions about what would help people to stay engaged or re-engage with services, perceptions about what happens to people after disengagement, and preferences for services that are currently inaccessible;

- Three questions asked about the use of digital mental health services;

- Eight questions were specifically for respondents who held private health insurance cover.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Survey Completion Rates

3.2. Most Common Mental Health Services Accessed during the Past 5 Years

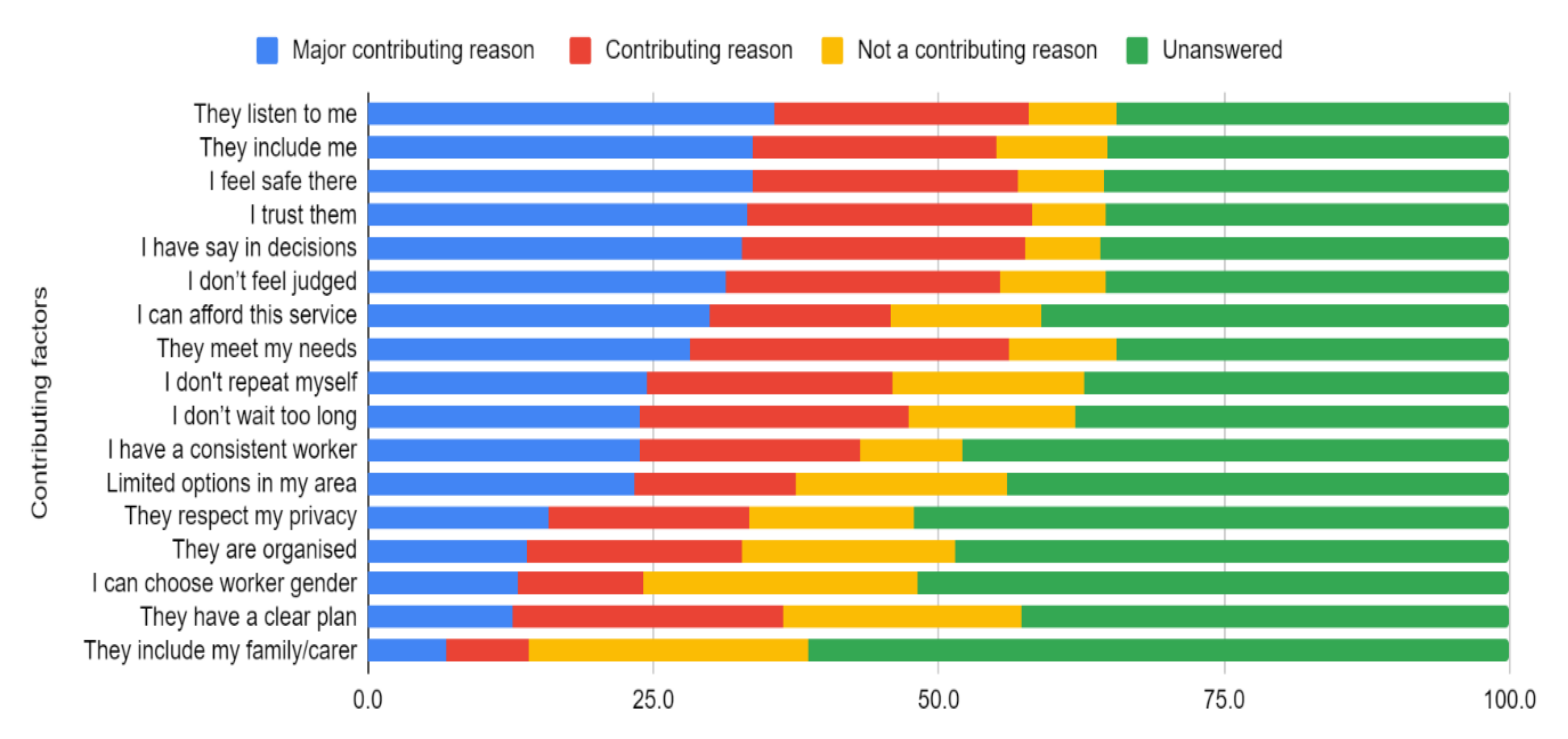

3.3. Reasons for Accessing Mental Health Services

3.4. Reasons for Disengagement

3.5. Most Common Mental Health Services Re-Engaged

3.6. Comparing Mental Health Providers

4. Discussion

4.1. Why Consumers Choose Certain MHS

4.2. Why Consumers Disengage from MHS and How They Could Be Re-Engaged

4.3. Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social Determinants of Mental Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/gulbenkian_paper_social_determinants_of_mental_health/en/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Ghebreyesus, T.A. The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019–2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/310981/WHO-MSD-19.1-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Mental Health; Our World in Data: Oxford, UK, 2018; Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Carr, M.J.; Steeg, S.; Webb, R.T.; Kapur, N.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Abel, K.M.; Hope, H.; Pierce, M.; Ashcroft, D.M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care-recorded mental illness and self-harm episodes in the UK: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Pub Health 2021, 6, E124–E135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerissen, H.; Duckett, S. A Primary Health Network Redesign to Address the ‘Missing Middle’ in Mental Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.croakey.org/a-phn-redesign-to-address-the-missing-middle-in-mental-health/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Productivity Commission. Mental Health, Report no. 95; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/report (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Fleury, M.; Imboua, A.; Aube, D.; Farand, L.; Lambert, Y. General practitioners’ management of mental disorders: A rewarding practice with considerable obstacles. BMC Fam. Pract. 2012, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, E.L.; Banfield, M.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Hatfield, T.; Kyrios, M. Contemporary treatment of anxiety in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes in countries with universal healthcare. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, P.; Windfuhr, K.; Pearson, A.; Da Cruz, D.; Miles, C.; Cordingley, L.; While, D.; Swinson, N.; Williams, A.; Shaw, J.; et al. Suicide prevention in primary care: General practitioners’ views on service availability. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Pathways of Recovery: Preventing Further Episodes of Mental Illness (Monograph): The Role of Primary Care Including General Practice. 2006. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-p-mono-toc~mental-pubs-p-mono-bas~mental-pubs-p-mono-bas-acc~mental-pubs-p-mono-bas-acc-pri (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Menear, M.; Dugas, E.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Dogba, M.J.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Gervais, M.; Gilbert, M.; Houle, J.; Kates, N.; Knowles, S.; et al. Strategies for engaging patients and families in collaborative care programs for depression and anxiety disorders: A systematic review. J. Affect. Dis. 2020, 263, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, A.; Fahmy, R.; Singh, S.P. Disengagement from mental health services: A literature review. Soc. Psych. Psychiatr. Epidem. 2009, 44, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeg, D.; van de Goor, I.; Garretsen, H. Predicting Initial Client Engagement with Community Mental Health Services by Routinely Measured Data. Comm. Ment. Health J. 2015, 51, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, T.E.; Easter, A.; Pollock, M.; Pope, L.G.; Wisdom, J.P. Disengagement from care: Perspectives of individuals with serious mental illness and of service providers. Psychiatri. Serv. 2013, 64, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreyenbuhl, J.; Nossel, I.R.; Dixon, L.B. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: A review of the literature. Schiz. Bull. 2009, 35, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Watts, J.; Chase, M.; Matanov, A. Processes of disengagement and engagement in assertive outreach patients: Qualitative study. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2005, 187, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Victoria. Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Final Report, Summary and Recommendations, Parl Paper No. 202, Session 2018–21 (Document 1 of 6). 2021. Available online: https://finalreport.rcvmhs.vic.gov.au/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Newman, D.; O’Reilly, P.; Lee, S.H.; Kennedy, C. Mental health service users’ experiences of mental health care: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Staniszewska, S.; Mockford, C.; Chadburn, G.; Fenton, S.J.; Bhui, K.; Larkin, M.; Newton, E.; Crepaz-Keay, D.; Griffiths, F.; Weich, S. 2019 Experiences of in-patient mental health services: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2019, 214, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chadwick, A.; Street, C.; McAndrew, S.; Deacon, M. Minding our own bodies: Reviewing the literature regarding the perceptions of service users diagnosed with serious mental illness on barriers to accessing physical health care. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 21, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lived Experience Australia Ltd. Available online: https://www.livedexperienceaustralia.com.au/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Kaine, C.; Lawn, S. The ‘Missing Middle’ Our Voices. 2021. Available online: https://www.livedexperienceaustralia.com.au/missingmiddlemedia (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Biringer, E.; Hartveit, M.; Sundfør, B.; Ruud, T.; Borg, M. Continuity of care as experienced by mental health service users-a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Damarell, R.A.; Morgan, D.D.; Tieman, J.J. General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Martínez, C.; Sánchez-Martínez, V.; Ballester-Artínez, J.; Richart-Martínez, M.; Ramos-Pichardo, J.D. A qualitative emancipatory inquiry into relationships between people with mental disorders and health professionals. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraw, B.W. The nature of epistemic trust. Soc. Epistem. 2015, 29, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A.; Flood, C.; Rowe, J.; Quigley, J.; Henry, S.; Hall, C.; Evans, R.; Sherman, P.; Bowers, L. Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial to measure the clinical and cost effectiveness of peer support in increasing hope and quality of life in mental health patients discharged from hospital in the UK. BMC Psychiatr. 2014, 14, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, S.; Foster, R.; Marks, J.; Morshead, R.; Goldsmith, L.; Barlow, S.; Sin, J.; Gillard, S. The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatr. 2020, 20, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtila, L.; Ashfaq, I.; Ampofo, A.; Dawson, D.; Selby, P. Engaging a person with lived experience of mental illness in a collaborative care model feasibility study. BMC Res. Involve. Engage. 2021, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, S.J.; Nieboer, A.P.; Cramm, J.M. Easier Said Than Done: Healthcare Professionals’ Barriers to the Provision of Patient-Centered Primary Care to Patients with Multimorbidity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Social Prescribing Roundtable, November 2019: Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/RACGP/Advocacy/Social-prescribing-report-and-recommendation.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Moore, K.L.; Lopez, L.; Camacho, D.; Munson, M.R. A Qualitative Investigation of Engagement in Mental Health Services Among Black and Hispanic LGB Young Adults. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfield, M.; Farrer, L.M.; Harrison, C. Management or missed opportunity? Mental health care planning in Australian general practice. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2019, 25, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trankle, S.A.; Usherwood, T.; Abbott, P.; Roberts, M.; Crampton, M.; Girgis, C.M.; Riskallah, J.; Chang, Y.; Saini, J.; Reath, J. Integrating health care in Australia: A qualitative evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Mental Health Service | N | % of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| My GP | 197 | 69.12 |

| A psychologist, counsellor/therapist | 185 | 65.91 |

| Public mental health services/hospitals/community teams | 106 | 37.89 |

| Peer support (organized or unorganized) | 89 | 31.23 |

| Private mental health services/hospitals | 74 | 25.96 |

| Online or digital resources or apps | 69 | 24.21 |

| Only used a private psychiatrist | 57 | 20.00 |

| Telehealth | 54 | 18.95 |

| Veteran supports | 3 | 1.05 |

| Other # | 9 | 3.16 |

| Total | 848 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lawn, S.; Kaine, C.; Stevenson, J.; McMahon, J. Australian Mental Health Consumers’ Experiences of Service Engagement and Disengagement: A Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910464

Lawn S, Kaine C, Stevenson J, McMahon J. Australian Mental Health Consumers’ Experiences of Service Engagement and Disengagement: A Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910464

Chicago/Turabian StyleLawn, Sharon, Christine Kaine, Jeremy Stevenson, and Janne McMahon. 2021. "Australian Mental Health Consumers’ Experiences of Service Engagement and Disengagement: A Descriptive Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910464

APA StyleLawn, S., Kaine, C., Stevenson, J., & McMahon, J. (2021). Australian Mental Health Consumers’ Experiences of Service Engagement and Disengagement: A Descriptive Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910464