A Pilot Study on the Contamination of Assistance Dogs’ Paws and Their Users’ Shoe Soles in Relation to Admittance to Hospitals and (In)Visible Disability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Coding

2.2.2. Sampling and Preservation

2.2.3. Processing of Enterobacteriaceae Samples

2.2.4. Processing of Clostridium difficile Samples

2.2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sampling Results

3.1.1. Enterobacteriaceae: Comparing of Groups

- Dog versus human. When comparing the mean recovered CFUs between humans and dogs, the two groups differed significantly (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01). As shown in Table 3, the mean of dogs is lower than that of humans, and thus the general hygiene of dog paws can be considered to be better than that of shoe soles.

- PD owner versus AD user. When comparing the mean recovered CFUs between PD owners and AD users, the two groups did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). The general hygiene of the shoe soles of PD owners and AD users can be considered equal.

- PD versus AD. When comparing the mean recovered CFUs between PDs and ADs, the two groups did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). The general hygiene of the paws of PDs and ADs can be considered equal.

3.1.2. Enterobacteriaceae: Comparing of Couples

- PD and PD owner couples. The p-value that was found for this comparison was very small (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01), which makes it very unlikely for the mean of the differences to be equal to zero. The general hygiene of the paws of PDs is considered to be better than the shoe soles of their owners.

- AD and AD user couples. Although the mean recovered CFUs of ADs was found to be lower than that of their users, it was calculated that p > 0.05. The general hygiene of the paws of ADs and the shoe soles of their users can be considered equal.

3.1.3. C. difficile

3.1.4. Pseudomonas spp.

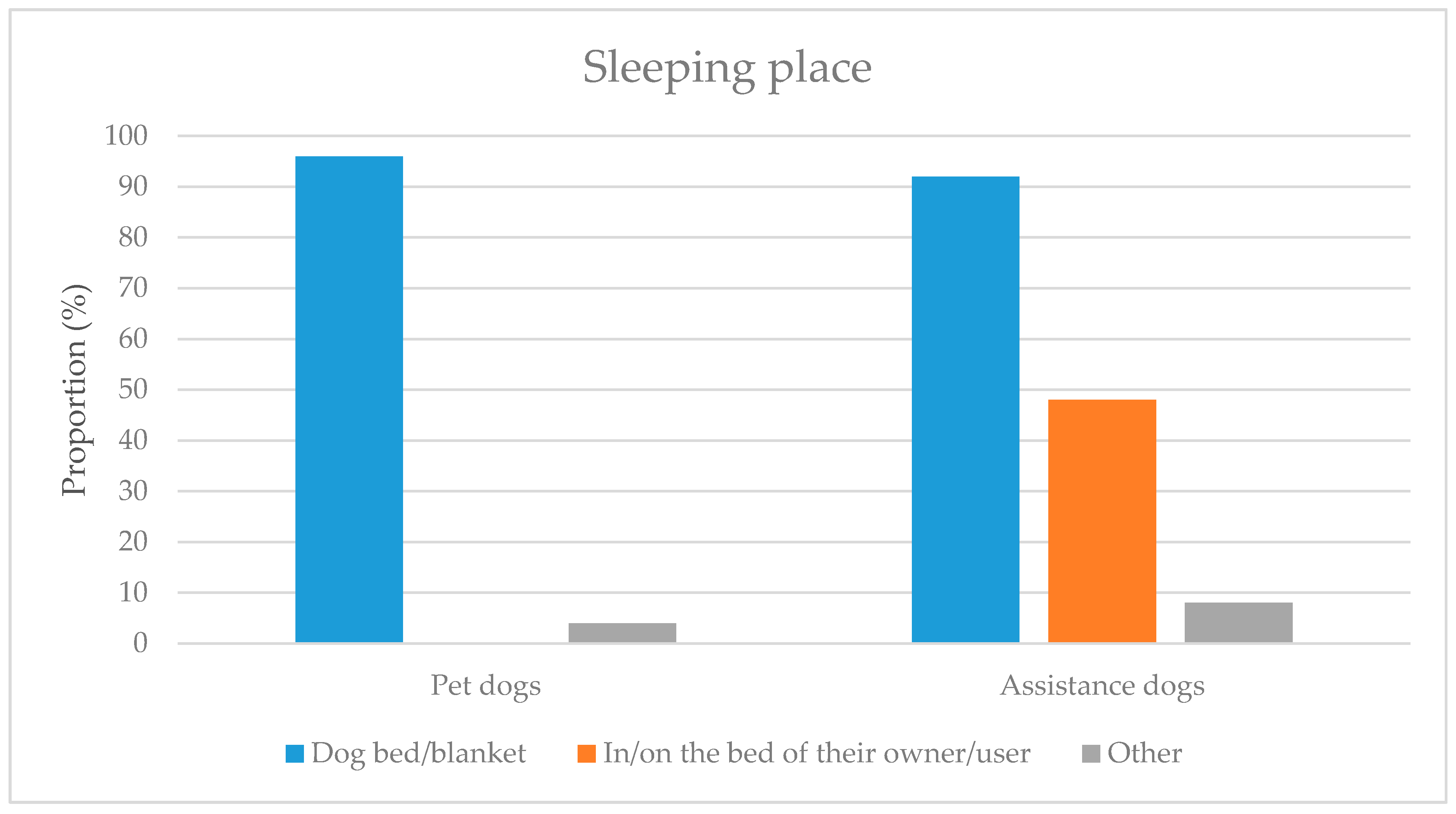

3.2. Enterobacteriaceae and Possible Factors

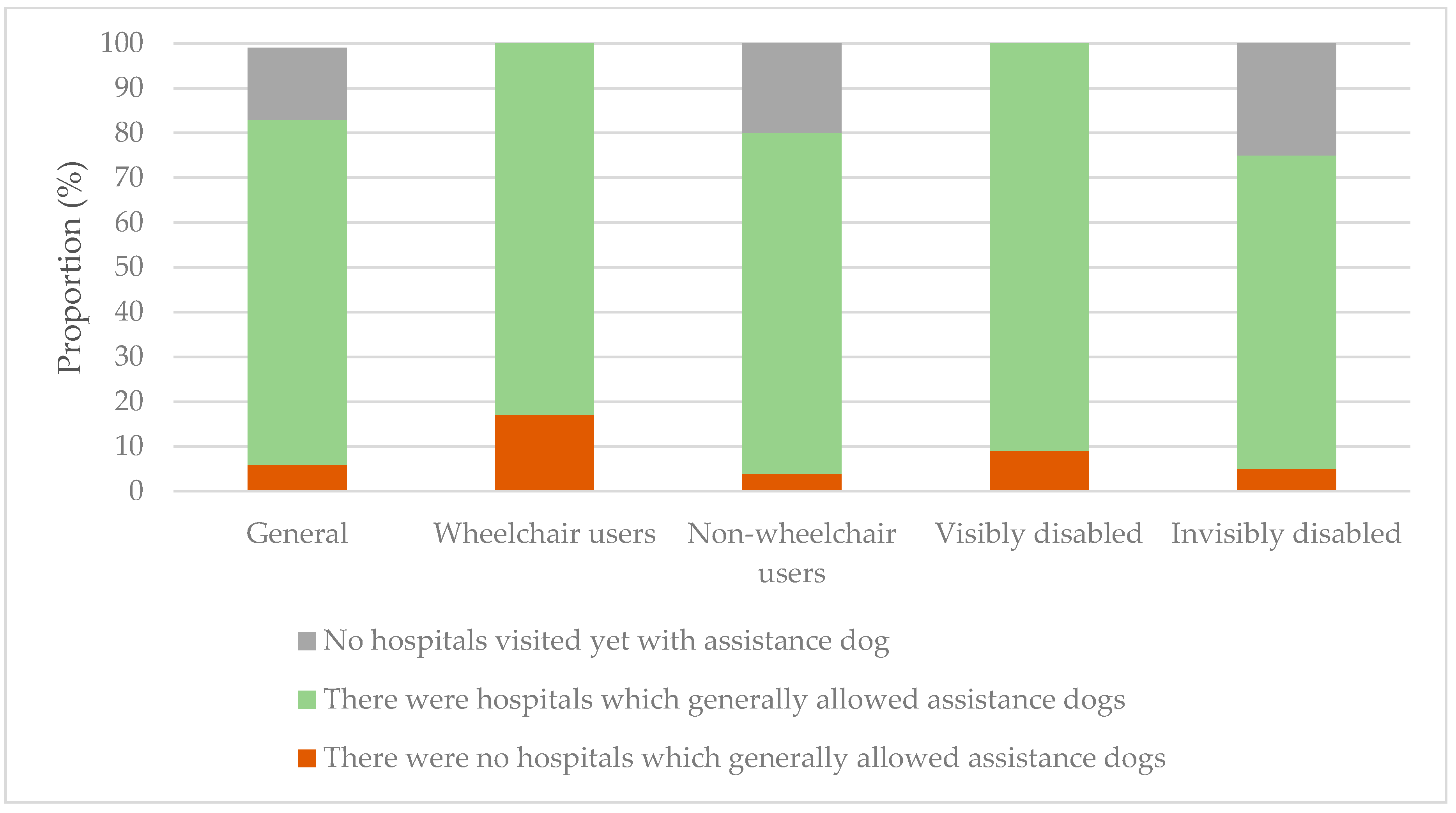

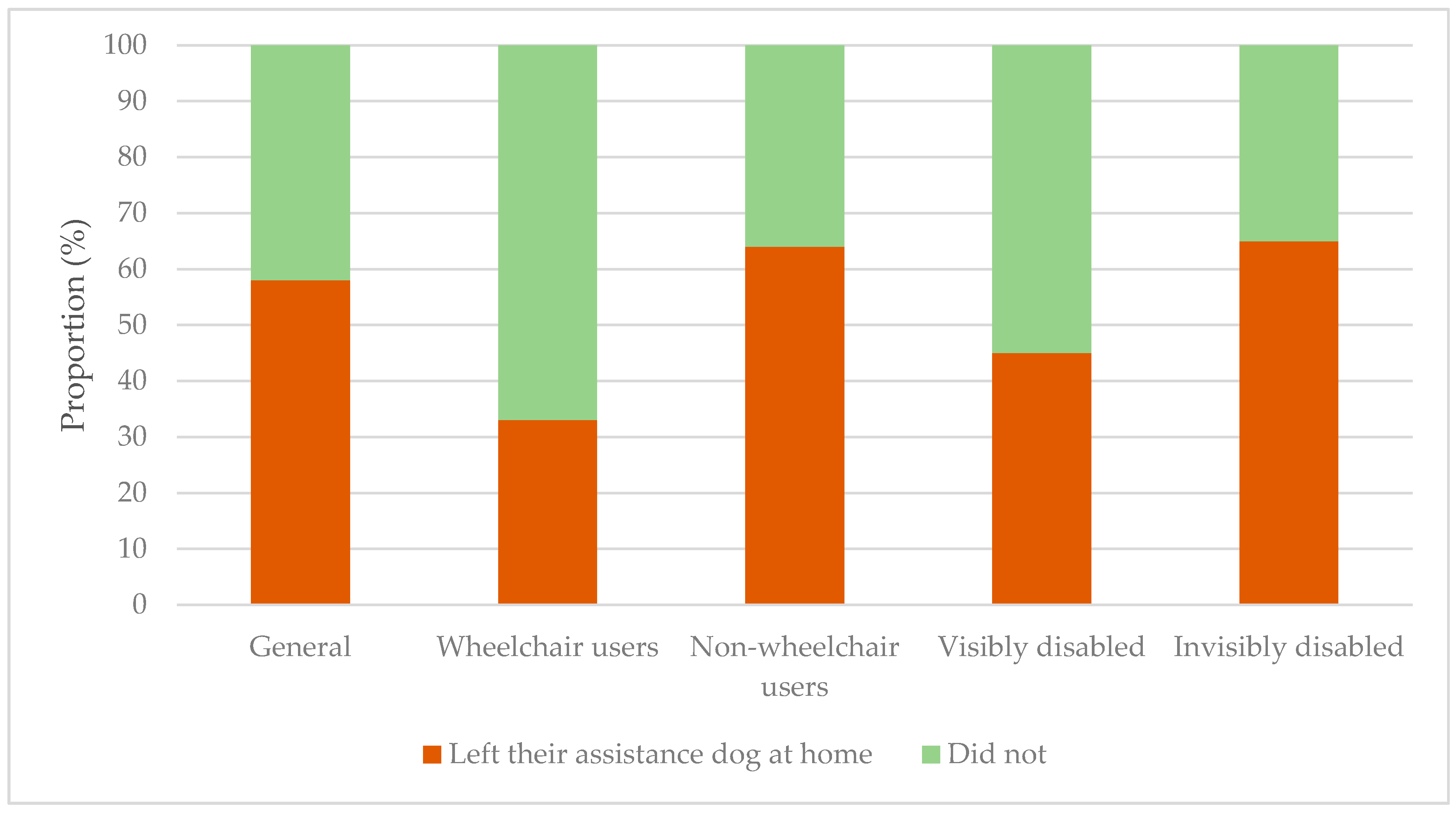

3.3. Experiences of AD Users in Public Places (Including Hospitals)

3.4. Hospitals and Visitor Numbers

3.4.1. Protocols

3.4.2. Visitor Numbers

4. Discussion

4.1. Sampling

4.1.1. Sampling Results

Enterobacteriaceae and General Hygiene

C. difficile

Pseudomonas spp.

4.1.2. Sample Size, Sampling Materials, and Methods

4.2. Factors: Linkage to Recovered CFUs

4.2.1. Identified Factors

4.2.2. Geological Location

4.2.3. Hypoallergenicity

4.2.4. Raw Meat as a Part of a Dog’s Diet

4.3. Experiences of AD Users

4.3.1. Results Experience Questionnaires

4.3.2. Improvements Suggested by Participants

4.4. Results of Hospital Questionnaires

4.5. Trifecta of Law, Study Results, and Visitor Numbers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Couple Code | Individual Code | Recovered CFUs Enterobacteriaceae | C. difficile Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected | UV Light Fluorescence | |||

| AD-01 | AD-01-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-01-O | 0 | - | - | |

| AD-02 | AD-02-D | 1.5 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-02-O | 9.0 × 102 | - | - | |

| AD-03 | AD-03-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-03-O | 0 | yes | - | |

| AD-04 | AD-04-D | 3.0 × 103 | yes | - |

| AD-04-O | 8.7 × 105 | yes | - | |

| AD-05 | AD-05-D | 2.2 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-05-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| AD-06 | AD-06-D | 1.9 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-06-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| AD-07 | AD-07-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-07-O | 1.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-08 | AD-08-D | 0 | yes | - |

| AD-08-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | yes | - | |

| AD-09 | AD-09-D | 7.0 × 102 | - | - |

| AD-09-O | 1.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-10 | AD-10-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| AD-10-O | 0 | - | - | |

| AD-11 | AD-11-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | yes | - |

| AD-11-O | 2.2 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-12 | AD-12-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-12-O | 0 | - | - | |

| AD-13 | AD-13-D | 0 | yes | - |

| AD-13-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | yes | - | |

| AD-14 | AD-14-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-14-O | 6.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-15 | AD-15-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-15-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| AD-16 | AD-16-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| AD-16-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| AD-17 | AD-17-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-17-O | 8.0 × 102 | yes | - | |

| AD-18 | AD-18-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| AD-18-O | 6.0 × 104 | yes | yes | |

| AD-19 | AD-19-D | 4.2 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-19-O | 0 | yes | - | |

| AD-20 | AD-20-D | 1.2 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-20-O | 7.1 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-21 | AD-21-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-21-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| AD-22 | AD-22-D | 1.5 × 104 | - | - |

| AD-22-O | 7.0 × 102 | - | - | |

| AD-23 | AD-23-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-23-O | 4.6 × 103 | - | - | |

| AD-24 | AD-24-D | 0 | - | - |

| AD-24-O | 0 | - | - | |

| AD-25 | AD-25-D | 1.0 × 103 | - | - |

| AD-25-O | 4.8 × 103 | - | - | |

| Couple Code | Individual Code | Recovered CFUs Enterobacteriaceae | C. difficile Presence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected | UV Light Fluorescence | |||

| PD-01 | PD-01-D | 1.3 × 105 | yes | - |

| PD-01-O | 4.3 × 106 | yes | - | |

| PD-02 | PD-02-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-02-O | 0 | yes | - | |

| PD-03 | PD-03-D | 0 | yes | - |

| PD-03-O | 0 | - | - | |

| PD-04 | PD-04-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-04-O | 3.6 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-05 | PD-05-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-05-O | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - | |

| PD-06 | PD-06-D | 8.5 × 103 | - | - |

| PD-06-O | 1.1 × 104 | - | - | |

| PD-07 | PD-07-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-07-O | 4.9 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-08 | PD-08-D | 1.3 × 103 | - | - |

| PD-08-O | 3.3 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-09 | PD-09-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-09-O | 0 | - | - | |

| PD-10 | PD-10-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-10-O | 7.0 × 104 | - | - | |

| PD-11 | PD-11-D | 0 | yes | - |

| PD-11-O | 1.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-12 | PD-12-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-12-O | 0 | - | - | |

| PD-13 | PD-13-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-13-O | 7.0 × 102 | - | - | |

| PD-14 | PD-14-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-14-O | 2.7 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-15 | PD-15-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-15-O | 1.4 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-16 | PD-16-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-16-O | 3.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-17 | PD-17-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-17-O | 3.0 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-18 | PD-18-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-18-O | 0 | - | - | |

| PD-19 | PD-19-D | 8.0 × 102 | - | - |

| PD-19-O | 2.7 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-20 | PD-20-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-20-O | 7.7 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-21 | PD-21-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-21-O | 7.1 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-22 | PD-22-D | 9.0 × 102 | - | - |

| PD-22-O | 1.7 × 103 | - | - | |

| PD-23 | PD-23-D | 0 | - | - |

| PD-23-O | 0 | yes | - | |

| PD-24 | PD-24-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-24-O | 1.7 × 102 | - | - | |

| PD-25 | PD-25-D | 0 (<7 × 102) | - | - |

| PD-25-O | 0 | - | - | |

References

- Commission Assistentiehonden. Available online: https://www.nen.nl/Standardization/Join-us/Technical-committees-and-new-subjects/TC-Industry-Logistics-Transport/Assistentiehonden.htm (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Hondenscholen Voor Assistentiehonden. Available online: https://stichtinggebruikersassistentiehonden.nl/hondenscholen/ (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Results for Members Serving Netherlands. Available online: https://assistancedogsinternational.org/index.php?src=directory&view=programs&category=Netherlands (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Hoek, N.; de Bruin, P.; Oort, N. Jaarbericht 2019; Koninklijk Nederlands Geleidehondenfonds (KNGF): Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Promoting the Rights of Assistance Dog Users. Available online: https://www.iapb.org/news/promoting-the-rights-of-assistance-dog-users/ (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Deur Staat op Kier Voor Geleidehond. Available online: https://geleidehond.nl/artikel/deur-staat-op-kier-voor-geleidehond (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Audrestch, H.M.; Whelan, C.T.; Grice, D.; Asher, L.; England, G.; Freeman, S.L. Recognizing the value of assistance dogs in society. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assistance Dogs International-Terms & Definitions. Available online: https://assistancedogsinternational.org/resources/adi-terms-definitions/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; Article 19 and 20; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Wet Gelijke Behandeling op Grond van Handicap of Chronische Ziekte; Paragraph 1, article 2; Dutch Government: ’s-Gravenhage, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Barco, L.; Belluco, S.; Roccato, A.; Ricci, A. Escherichia coli and Enterobacteriaceae counts on pig and ruminant carcasses along the slaughterline, factors influencing the counts and relationship between visual faecal contamination of carcasses and counts: A review. EFSA Supporting Publ. 2014, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare Facilities: Information about Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cre/cre-facilities.html (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Lefebvre, S.L.; Waltner-Toews, D.; Peregrine, A.S.; Reid-Smith, R.; Hodge, L.; Arroyo, L.G.; Weese, J.S. Prevalence of zoonotic agents in dogs visiting hospitalized people in Ontario: Implications for infection control. J. Hosp. Infect. 2006, 62, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janezic, S.; Mlakar, S.; Rupnik, M. Dissemination of Clostridium difficile spores between environment and households: Dog paws and shoes. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanen, L.A. The Zoonotic Risks of Sleeping with Pets. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. Available online: http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/369927 (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Song, S.J.; Lauber, C.; Costello, E.K.; Lozupone, C.A.; Humphrey, G.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Caporaso, J.G.; Knights, D.; Clemente, J.C.; Nakielny, S.; et al. Cohabiting family members share microbiota with one another and with their dogs. Elife 2013, 2, e00458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtains as a Source of Clostridium difficile: The Importance of Sampling Methods. Available online: https://www.mwe.co.uk/modules/downloadable_files/assets/p2244.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Product Detail: Brazier’s Clostridium Difficile Selective Agar. Available online: http://www.oxoid.com/UK/blue/prod_detail/prod_detail.asp?pr=PB1055&c=UK&lang=EN (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Ziekenhuiszorg-Cijfers & Context-Aanbod. Available online: https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/ziekenhuiszorg/cijfers-context/aanbod#node-aantal-instellingen-voor-medisch-specialistische-zorg (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Kengetallen Umc’s 2017. Available online: https://www.nfu.nl/over/kengetallen-umcs-2017 (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Hoe Gaat Het? Available online: https://www.umcutrecht.nl/nieuws/hoe-gaat-het (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Geleverde Zorg in Ziekenhuizen. Available online: https://ziekenhuiszorgincijfers.nl/geleverde-zorg-in-ziekenhuizen (accessed on 29 August 2020).

- Dutch Hospital Data, (Rapportage Enquête Jaarcijfers Ziekenhuizen 2017; Dutch Hospital Data (DHD): Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Beerda, B.; Schilder, M.B.; van Hooff, J.A.; de Vries, H.W.; Mol, J.A. Chronic stress in dogs subjected to social and spatial restriction. I. Behavioral responses. Physiol. Behav. 1999, 66, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaauw, P.; van Knapen, F. Is being licked by dogs not dirty? Tijdschr. Voor Diergeneeskd. 2012, 137, 594–596. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, A.; Barrera, R.; Lopez, R.; Mane, M.C.; Rodriguez, J.; Molleda, J.M. Immunoglobulin identification and quantification in parotid saliva in dogs. Acta Med. Vet. 1991, 37, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tenovuo, J.; Illukka, T.; Vähä-Vahe, T. Non-immunoglobulin defense factors in canine saliva and effects of a tooth gel containing antibacterial enzymes. J. Vet. Dent. 2000, 17, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpomie, O.O.; Ukoha, P.; Nwafor, O.E.; Umukoro, G. Saliva of different dog breeds as antimicrobial agents against microorganisms isolated from wound infections. Anim. Sci. J. 2011, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.L.; Powell, K.L. Antibacterial properties of saliva: Role in maternal periparturient grooming and in licking wounds. Physiol. Behav. 1990, 48, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.E.; Kim, Y.J.; Do, K.H.; Kim, J.K.; Ham, J.S.; Lee, W.K. Effects of Queso Blanco Cheese Containing Bifidobacterium longum KACC 91563 on the Intestinal Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acid in Healthy Companion Dogs. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018, 38, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgarth, M.; Lehner, E.M.; Behr, J.; Vogel, R.F. Diversity and anaerobic growth of Pseudomonas spp. isolated from modified atmosphere packaged minced beef. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedzyk, L.; Wang, T.; Ye, R.W. The Periplasmic Nitrate Reductase in Pseudomonas sp. Strain G-179 Catalyzes the First Step of Denitrification. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 2802–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, A.; Allen, J.R.; Burke, J.; Ducel, G.; Harris, A.; John, J.; Johnson, D.; Lew, M.; MacMillan, B.; Meers, P. Nosocomial infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Review of recent trends. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1983, 5, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulcahy, L.R.; Isabella, V.M.; Lewis, K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in disease. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, R.L.; Burns, J.L.; Ramsey, B.W. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 918–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vredegoor, D.W.; Willemse, T.; Chapman, M.D.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Krop, E.J.M. Can f 1 levels in hair and homes of different dog breeds: Lack of evidence to describe any dog breed as hypoallergenic. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Unterer, S.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Honneffer, J.B.; Guard, B.C.; Lidbury, J.A.; Steiner, J.M.; Fritz, J.; Kölle, P. The fecal microbiome and metabolome differs between dogs fed Bones and Raw Food (BARF) diets and dogs fed commercial diets. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bree, F.; Bokken, G.; Mineur, R.; Franssen, F.; Opsteegh, M.; van der Giessen, J.; Lipman, L.; Overgaauw, P. Zoonotic bacteria and parasites found in raw meat-based diets for cats and dogs. Vet. Rec. 2018, 182, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijdeveld, T.F.; Overgaauw, P. Follow-up Analysis: Is It Possible to Confirm and Extrapolate Parts of the Results of the Study ‘Zoonotic Bacteria and Parasites Found in Raw Meat-Based Diets for Cats an Dogs’ Focusing on Salmonella, E-coli and Thyroid Hormone Based on a Long-Term Study? Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Assistentiehond Altijd Welkom in Horeca. Available online: https://www.khn.nl/nieuws/assistentiehond-altijd-welkom-in-horeca (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Mag ik Huisdieren of Assistentiehonden Toelaten in Mijn Restaurant, Café of Supermarkt? Available online: https://www.nvwa.nl/documenten/vragen-en-antwoorden/mag-ik-huisdieren-of-assistentiehonden-toelaten-in-mijn-restaurant-cafe-of-supermarkt (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Homepage. Available online: https://stichtinggebruikersassistentiehonden.nl/ (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Assistentiehond Niet Afleiden! Available online: https://stichtinggebruikersassistentiehonden.nl/assistentiehond-niet-afleiden-het-is-verbazingwekkend-hoe-creatief-mensen-dat-proberen-uit-te-leggen/ (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Bucx, M.; Smit, I.; Kremer, M.; Buit, J. Onderzoek: Assistentiehonden Krijgen net zo veel Rust als een Huishond; HAS Hogeschool: ‘s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmardehei, M.; Alinejad, F.; Ansari, F.; Bahramian, M.; Barati, M. Effect of sticky mat usage in control of nosocomial infection in motahary burn hospital. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2016, 8, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaya, H. Questions and answers. J. Hosp. Infect. 1980, 1, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Poblete, K.; Amadio, J.; Hasan, I.; Begum, K.; Alam, M.J.; Garey, K.W. Evaluation of a shoe sole UVC device to reduce pathogen colonization on floors, surfaces and patients. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wet op de Dierproeven; Paragraph 1, article 1; Dutch Government: Baarn, the Netherlands, 2019.

| t-tests | Human vs. dog | H0 = there is no difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right front paws of dogs and the right shoe soles of humans. |

| H1 = there is a difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right front paws of dogs and the right shoe soles of humans. | ||

| Pet dog owners vs. assistance dog users | H0 = there is no difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right shoe soles of pet dog owners and the right shoe soles of assistance dog users. | |

| H1 = there is a difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right shoe soles of pet dog owners and the right shoe soles of assistance dog users. | ||

| Pet dogs vs. assistance dogs | H0 = there is no difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right front paws of pet dogs and the right front paws of assistance dogs. | |

| H1 = there is a difference between the mean number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from the right front paws of pet dogs and the right front paws of assistance dogs. | ||

| Paired t-tests | Pet dog vs. pet dog owner | H0 = the mean of the differences, between the number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from pet dogs’ right front paws and their owners’ right shoe sole, is zero. |

| H1 = the mean of the differences, between the number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from pet dogs’ right front paws and their owners’ right shoe sole, is not zero. | ||

| Assistance dog vs. assistance dog user | H0 = the mean of the differences, between the number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from assistance dogs’ right front paws and their users’ right shoe sole, is zero. | |

| H1 = the mean of the differences, between the number of colony-forming units of bacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family recovered from assistance dogs’ right front paws and their users’ right shoe sole, is not zero. |

| Type of Disability | Examples of Visible or Invisible Disabilities | Examples of Frequently Used Types of ADs |

|---|---|---|

| Visible | Visual impairment (usage of red and white cane); | Guide dogs; |

| Impaired mobility (usage of wheelchair) | Mobility assistance dogs | |

| Invisible | Hearing impairment; | Hearing dogs; |

| Impaired mobility (usage of walker or normal cane); | Mobility assistance dogs; | |

| Epilepsy, diabetes; | Alert service dogs, response service dogs; | |

| PTSD, autism | Psychiatric service dogs |

| Group | Recovered CFUs * Enterobacteriaceae | C. difficile Presence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Absolute Numbers) | Mean (Logarithms) | Suspicion | UV Light Fluorescence | |

| Dogs | 3444 | 0.9604 | 7 | 0 |

| Humans | 107,893 | 2.1286 | 9 | 1 |

| Assistance dogs | 1228 | 1.2000 | 4 | 0 |

| Assistance dog users | 38,364 | 1.7496 | 6 | 1 |

| Pet dogs | 5660 | 0.7208 | 3 | 0 |

| Pet dog owners | 177,422 | 2.5076 | 3 | 0 |

| Factors | Number of Dogs | Factors | ORs | 95% CIs | p-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFUs Present (n = 14) | CFUs Absent (n = 36) | |||||

| Dog type: assistance dog | 9 (36%) | 16 (64%) | Being a pet dog | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 | 0.2 |

| Dog type: pet dog | 5 (20%) | 20 (80%) | ||||

| Worm control | 13 (37%) | 22 (63%) | Not being on worm control | 0.1 | 0.006–0.7 | 0.05 |

| No worm control | 1 (7%) | 14 (93%) | ||||

| Other elements present in diet | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | Not having other elements in their diets | 0.3 | 0.06–1.5 | 0.1 |

| No other elements present (other than kibble, canned food, or raw meat) | 10 (24%) | 32 (76%) | ||||

| Neighbourhood as visited location during walks | 11 (24%) | 34 (76%) | Not having “neighbourhood” as a location visited | 4.6 | 0.7–38.8 | 0.1 |

| No neighbourhood as visited location | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | ||||

| Age (in years): 0–1 | 2 (18%) | 9 (82%) | ||||

| Age: 2–5 | 3 (20%) | 12 (80%) | Age: 2–5 | 1.1 | 0.2–9.9 | 0.9 |

| Age: 6–7 | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | Age: 6–7 | 1.5 | 0.2–13.6 | 0.7 |

| Age: 8–13 | 6 (50%) | 6 (50%) | Age: 8–13 | 4.5 | 0.7–38.6 | 0.1 |

| Vaccinated against rabies | 10 (37%) | 17 (63%) | Not being vaccinated against rabies | 0.4 | 0.09–1.3 | 0.1 |

| Not vaccinated against rabies | 4 (17%) | 19 (83%) | ||||

| Sleeping place: bench or dog bed/blanket | 12 (26%) | 35 (74%) | Not having bench or dog bed/blanket as sleeping place | 5.8 | 0.5–132.4 | 0.2 |

| Sleeping place: not bench or dog bed/blanket | 2 (67%) | 1 (33%) | ||||

| Factors | ORs | 95% CIs | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not being on worm control | 0.04 | 0.001–0.4 | 0.007 |

| Not having other elements in their diets (other than kibble, canned food, or raw meat) | 0.06 | 0.002–0.5 | 0.007 |

| Not having “neighbourhood” as a location visited during walks | 15.8 | 1.4–339.0 | 0.04 |

| Public knowledge | For whom? | Civilians visiting public places. |

| Security guards. | ||

| Store personnel. | ||

| People working in the hospitality industry. | ||

| Company owners. | ||

| Healthcare workers. | ||

| Other organisations. | ||

| About what? | The fact that every AD or AD in training has an identification card, that shows that it is a certified AD, coming from an official and licensed organisation, and the name of its user. | |

| Education about hygiene and the impact of ADs on hygiene. | ||

| Education about the reason and need for an AD, and the fact that an AD is something completely different to a pet dog. | ||

| Education about the types of ADs, as people are often only familiar with the guide dog type. | ||

| Dealing with ADs as a non-user: no touching, no talking, no eye contact, ignore the AD (even when it approaches you), keep yourself and your own dog at a distance. | ||

| Education about invisible diseases, as people tend to not recognise these diseases and are often biased. | ||

| Education about the used terms regarding ADs, and the use of standardised terms, set up by Assistance Dogs International (ADI). | ||

| More research on the effect of ADs on their users and corresponding publicity. | ||

| Overall understanding, clarity, and acceptance. | ||

| Infrastructure public space | What? | More space for ADs on public transport; they often have to lie down in the aisle, which can be potentially dangerous, for both people and ADs. |

| Not constructing shared places in traffic, especially for people with a visual impairment; they have no orientation and they cannot make eye contact with motorists. | ||

| The availability of an elevator at all times; this is obviously important for wheelchair users, but also when there are only escalators (the fur on dog paws can get caught between the steps). | ||

| Facilitating vacations for ADs and their users; they are often denied in dog-free accommodations. This limits the range of choice and makes the AD user very dependent on certain resorts, hotels, organisations, et cetera. This also applies to transport by taxi. | ||

| It should be noted that revolving doors are an issue for guide dog users. | ||

| Identification and welcoming of ADs | What? | Stickers near the entrances of public buildings, indicating that ADs are welcome. These stickers already exist, but they are only present in small numbers, and frequently targeted at a single type of ADs, most often guide dogs. |

| Uniform AD harnesses for every type of AD, regardless of which organisation they are from, which can be recognised by any civilian. | ||

| Education and publicity on these stickers and harnesses, plus information about imitation harnesses of non-official ADs (sometimes even pet dogs). | ||

| Education about communication with AD users: how to handle the situation correctly? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vos, S.J.; Wijnker, J.J.; Overgaauw, P.A.M. A Pilot Study on the Contamination of Assistance Dogs’ Paws and Their Users’ Shoe Soles in Relation to Admittance to Hospitals and (In)Visible Disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020513

Vos SJ, Wijnker JJ, Overgaauw PAM. A Pilot Study on the Contamination of Assistance Dogs’ Paws and Their Users’ Shoe Soles in Relation to Admittance to Hospitals and (In)Visible Disability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020513

Chicago/Turabian StyleVos, S. Jasmijn, Joris J. Wijnker, and Paul A. M. Overgaauw. 2021. "A Pilot Study on the Contamination of Assistance Dogs’ Paws and Their Users’ Shoe Soles in Relation to Admittance to Hospitals and (In)Visible Disability" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020513

APA StyleVos, S. J., Wijnker, J. J., & Overgaauw, P. A. M. (2021). A Pilot Study on the Contamination of Assistance Dogs’ Paws and Their Users’ Shoe Soles in Relation to Admittance to Hospitals and (In)Visible Disability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020513