Prenatal Environmental Metal Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

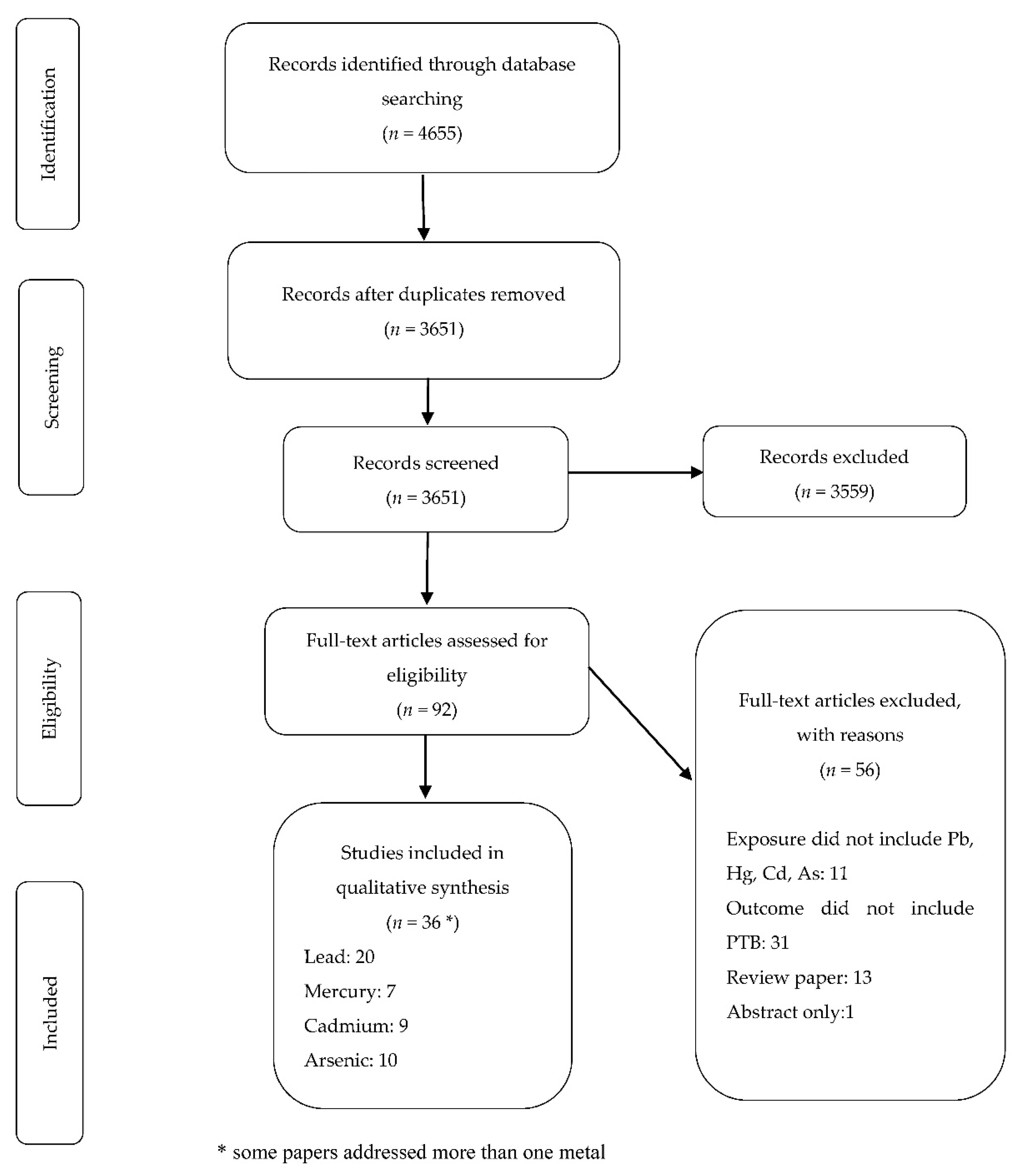

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Criteria

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening of Papers

2.4. Data Abstraction

2.5. Data Charting Process

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Lead and PTB

3.2. Mercury and PTB

3.3. Cadmium and PTB

3.4. Arsenic and PTB

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harrison, M.S.; Goldenberg, R.L. Global burden of prematurity. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 21, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academy of Sciences. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention; Behrman, R.E., Butler, A.S., Eds.; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Oestergaard, M.Z.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.B.; Narwal, R.; Adler, A.; Vera Garcia, C.; Rohde, S.; Say, L.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012, 379, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, M.M.; Morrison, J.J. Preterm delivery. Lancet 2002, 360, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; Culhane, J.F.; Iams, J.D.; Romero, R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008, 371, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Chu, Y.; Perin, J.; Zhu, J.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–2015: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2016, 388, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muglia, L.J.; Katz, M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.K.; Chin, H.B. Environmental chemicals and preterm birth: Biological mechanisms and the state of the science. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.K.; O’Neill, M.S.; Meeker, J.D. Environmental contaminant exposures and preterm birth: A comprehensive review. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B Crit. Rev. 2013, 16, 69–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpora, M.G.; Piacenti, I.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Masciullo, L.; Rech, F.; Benedetti Panici, P. Environmental Contaminants Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review. Toxics 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Kumarathasan, P.; Gomes, J. Infant and mother related outcomes from exposure to metals with endocrine disrupting properties during pregnancy. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 569–570, 1022–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; Anand, M.; Singh, S.; Taneja, A. Environmental toxic metals in placenta and their effects on preterm delivery-current opinion. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 43, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milton, A.H.; Hussain, S.; Akter, S.; Rahman, M.; Mouly, T.A.; Mitchell, K. A Review of the Effects of Chronic Arsenic Exposure on Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, R.; Armah, F.A.; Essumang, D.K.; Luginaah, I.; Clarke, E.; Marfoh, K.; Cobbina, S.J.; Nketiah-Amponsah, E.; Namujju, P.B.; Obiri, S.; et al. Association of arsenic with adverse pregnancy outcomes/infant mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, M.S.; Surdu, S.; Neamtiu, I.A.; Gurzau, E.S. Maternal arsenic exposure and birth outcomes: A comprehensive review of the epidemiologic literature focused on drinking water. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J. Meta Anal. 2017, 5, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreier, M. Quality Assessment in Meta-analysis. Methods of Clinical Epidemiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantonwine, D.; Hu, H.; Sánchez, B.N.; Lamadrid-Figueroa, H.; Smith, D.; Ettinger, A.S.; Mercado-García, A.; Hernández-Avila, M.; Wright, R.O.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M. Critical windows of fetal lead exposure: Adverse impacts on length of gestation and risk of premature delivery. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2010, 52, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, Z.; Price-Green, P.; Bove, F.J.; Kaye, W.E. Lead exposure and birth outcomes in five communities in Shoshone County, Idaho. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2006, 209, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, B.; Huo, W.; Cao, Z.; Liu, W.; Liao, J.; Xia, W.; Xu, S.; Li, Y. Fetal exposure to lead during pregnancy and the risk of preterm and early-term deliveries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Amaya, E.; Gil, F.; Murcia, M.; Llop, S.; Casas, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Lertxundi, A.; Irizar, A.; Fernández-Tardón, G.; et al. Placental metal concentrations and birth outcomes: The Environment and Childhood (INMA) project. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; Miles, S.Q.; Courtney, J.G.; Materna, B.; Charlton, V. Effect of magnitude and timing of maternal pregnancy blood lead (Pb) levels on birth outcomes. J. Perinatol. 2006, 26, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; Hao, J.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Fu, L.; Tao, F.B.; Xu, D.X. Maternal serum lead level during pregnancy is positively correlated with risk of preterm birth in a Chinese population. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.; Wright, R.O.; Amarasiriwardena, C.J.; Jayawardene, I.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E. Very low maternal lead level in pregnancy and birth outcomes in an eastern Massachusetts population. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Golding, J.; Emond, A.M. Adverse effects of maternal lead levels on birth outcomes in the ALSPAC study: A prospective birth cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, M.; Shibata, E.; Morokuma, S.; Tanaka, R.; Senju, A.; Araki, S.; Sanefuji, M.; Koriyama, C.; Yamamoto, M.; Ishihara, Y.; et al. The association between whole blood concentrations of heavy metals in pregnant women and premature births: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS). Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigeh, M.; Yokoyama, K.; Seyedaghamiri, Z.; Shinohara, A.; Matsukawa, T.; Chiba, M.; Yunesian, M. Blood lead at currently acceptable levels may cause preterm labour. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 68, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, K.M.; Mar, O.; Kosaka, S.; Umemura, M.; Watanabe, C. Prenatal Heavy Metal Exposure and Adverse Birth Outcomes in Myanmar: A Birth-Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Xia, W.; Li, Y.; Bassig, B.A.; Zhou, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Hu, J.; Du, X.; et al. Prenatal exposure to lead in relation to risk of preterm low birth weight: A matched case-control study in China. Reprod. Toxicol. 2015, 57, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Fitzgerald, E.F.; Gelberg, K.H.; Lin, S.; Druschel, C.M. Maternal low-level lead exposure and fetal growth. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1471–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, M.; Mehrotra, P.K.; Kumar, P.; Siddiqui, M.K.J. Placental lead-induced oxidative stress and preterm delivery. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2009, 27, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sawi, I.R.; El Saied, M.H. Umbilical cord-blood lead levels and pregnancy outcome. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 8, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Falcon, M.; Vinas, P.; Luna, A. Placental lead and outcome of pregnancy. Toxicology 2003, 185, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwinda, R.; Wibowo, N.; Putri, A.S. The Concentration of Micronutrients and Heavy Metals in Maternal Serum, Placenta, and Cord Blood: A Cross-Sectional Study in Preterm Birth. J. Pregnancy 2019, 2019, 5062365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özsoy, G.; Türker, G.; Özdemir, S.; Gökalp, A.S.; Barutçu, U.B. The effect of heavy metals and trace elements in the meconium on preterm delivery of unknown etiology. Turk. Klin. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 32, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rabito, F.A.; Kocak, M.; Werthmann, D.W.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Palmer, C.D.; Parsons, P.J. Changes in low levels of lead over the course of pregnancy and the association with birth outcomes. Reprod. Toxicol. 2014, 50, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Derici, M.K.; Demir, E.; Apaydin, H.; Kocak, O.; Kan, O.; Gorkem, U. Is the Concentration of Cadmium, Lead, Mercury, and Selenium Related to Preterm Birth? Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Myers, R.; Wei, T.; Bind, E.; Kassim, P.; Wang, G.; Ji, Y.; Hong, X.; Caruso, D.; Bartell, T.; et al. Placental transfer and concentrations of cadmium, mercury, lead, and selenium in mothers, newborns, and young children. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashore, C.J.; Geer, L.A.; He, X.; Puett, R.; Parsons, P.J.; Palmer, C.D.; Steuerwald, A.J.; Abulafia, O.; Dalloul, M.; Sapkota, A. Maternal mercury exposure, season of conception and adverse birth outcomes in an urban immigrant community in Brooklyn, New York, U.S.A. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 8414–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, J.B.; Wagner Robb, S.; Puett, R.; Cai, B.; Wilkerson, R.; Karmaus, W.; Vena, J.; Svendsen, E. Mercury in fish and adverse reproductive outcomes: Results from South Carolina. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Risk Assessment Office; Environmental Health Department; Ministry of the Environment. The Exposure to Chemical Compounds in the Japanese People. 2017. Available online: http://www.env.go.jp/chemi/dioxin/pamph/cd/2017en_full.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Huang, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, T.; Li, Y.; Zhou, A.; Du, X.; Pan, X.; Yang, J.; Wu, C.; et al. Prenatal cadmium exposure and preterm low birth weight in China. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, J.E.; Valentiner, E.; Maxson, P.; Miranda, M.L.; Fry, R.C. Maternal cadmium levels during pregnancy associated with lower birth weight in infants in a North Carolina cohort. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Hu, Y.F.; Hao, J.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Su, P.Y.; Yu, Z.; Fu, L.; Tao, F.B.; Xu, D.X. Association of maternal serum cadmium level during pregnancy with risk of preterm birth in a Chinese population. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 216, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huo, W.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, T.; Li, Y.; Pan, X.; Liu, W.; Chang, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, A.; et al. Maternal urinary cadmium concentrations in relation to preterm birth in the Healthy Baby Cohort Study in China. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.A.; Sayed, M.H.; Barua, S.; Khan, M.H.; Faruquee, M.H.; Jalil, A.; Hadi, S.A.; Talukder, H.K. Arsenic in drinking water and pregnancy outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almberg, K.S.; Turyk, M.E.; Jones, R.M.; Rankin, K.; Freels, S.; Graber, J.M.; Stayner, L.T. Arsenic in drinking water and adverse birth outcomes in Ohio. Environ. Res. 2017, 157, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, S.K.; Stanley, J.A.; Taylor, R.J.; Sivakumar, K.K.; Arosh, J.A.; Zeng, L.; Pennathur, S.; Padmanabhan, V. Sexually Dimorphic Impact of Chromium Accumulation on Human Placental Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 161, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.L.; Lobdell, D.T.; Liu, Z.; Xia, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, Y.; Kwok, R.K.; Mumford, J.L.; Mendola, P. Maternal drinking water arsenic exposure and perinatal outcomes in inner Mongolia, China. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2010, 64, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.L.; Kile, M.L.; Rodrigues, E.G.; Valeri, L.; Raj, A.; Mazumdar, M.; Mostofa, G.; Quamruzzaman, Q.; Rahman, M.; Hauser, R.; et al. Prenatal arsenic exposure, child marriage, and pregnancy weight gain: Associations with preterm birth in Bangladesh. Environ. Int. 2018, 112, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ayotte, J.D.; Onda, A.; Miller, S.; Rees, J.; Gilbert-Diamond, D.; Onega, T.; Gui, J.; Karagas, M.; Moeschler, J. Geospatial association between adverse birth outcomes and arsenic in groundwater in New Hampshire, USA. Environ. Geochem. Health 2015, 37, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, P.; Hao, J.H.; Tao, F.B.; Xu, D.X. Maternal serum arsenic level during pregnancy is positively associated with adverse pregnant outcomes in a Chinese population. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 356, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Tsai, S.S.; Chuang, H.Y.; Ho, C.K.; Wu, T.N. Arsenic in drinking water and adverse pregnancy outcome in an arseniasis-endemic area in northeastern Taiwan. Environ. Res. 2003, 91, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the Identification and Management of Lead Exposure in Pregnant and Lactating Women; National Center for Enviornmental Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Controland Prevention. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. 2012. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Sep2012.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Milton, A.H.; Smith, W.; Rahman, B.; Hasan, Z.; Kulsum, U.; Dear, K.; Rakibuddin, M.; Ali, A. Chronic arsenic exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes in bangladesh. Epidemiology 2005, 16, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concha, G.; Nermell, B.; Vahter, M.V. Metabolism of inorganic arsenic in children with chronic high arsenic exposure in northern Argentina. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998, 106, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, H.X.; Wang, L. Cadmium: Toxic effects on placental and embryonic development. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 67, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, A.; Danielsson, B.R.; Dencker, L.; Vahter, M. Embryotoxicity of arsenite and arsenate: Distribution in pregnant mice and monkeys and effects on embryonic cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1984, 54, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omeljaniuk, W.J.; Socha, K.; Soroczynska, J.; Charkiewicz, A.E.; Laudanski, T.; Kulikowski, M.; Kobylec, E.; Borawska, M.H. Cadmium and Lead in Women Who Miscarried. Clin. Lab. 2018, 64, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Fatima, F.; Waheed, I.; Akash, M.S.H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gubory, K.H.; Fowler, P.A.; Garrel, C. The roles of cellular reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and antioxidants in pregnancy outcomes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1634–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Claud, E.C. Intrauterine Inflammation, Epigenetics, and Microbiome Influences on Preterm Infant Health. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2018, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilahur, N.; Vahter, M.; Broberg, K. The Epigenetic Effects of Prenatal Cadmium Exposure. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Mahabbat-e Khoda, S.; Rekha, R.S.; Gardner, R.M.; Ameer, S.S.; Moore, S.; Ekström, E.C.; Vahter, M.; Raqib, R. Arsenic-associated oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune disruption in human placenta and cord blood. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iavicoli, I.; Fontana, L.; Bergamaschi, A. The effects of metals as endocrine disruptors. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2009, 12, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, A.S.; Banker, M.; Goodrich, J.M.; Dolinoy, D.C.; Burant, C.; Domino, S.E.; Smith, Y.R.; Song, P.X.K.; Padmanabhan, V. Early pregnancy exposure to endocrine disrupting chemical mixtures are associated with inflammatory changes in maternal and neonatal circulation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, J.R.G.; Matthews, S.G.; Gibb, W.; Lye, S.J. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 514–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Narbad, A.; Chen, W. Dietary strategies for the treatment of cadmium and lead toxicity. Nutrients 2015, 7, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, N.; Deb, B.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Maiti, S. Arsenic-Induced Antioxidant Depletion, Oxidative DNA Breakage, and Tissue Damages are Prevented by the Combined Action of Folate and Vitamin B12. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 168, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozack, A.K.; Howe, C.G.; Hall, M.N.; Liu, X.; Slavkovich, V.; Ilievski, V.; Lomax-Luu, A.M.; Parvez, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shahriar, H.; et al. Betaine and choline status modify the effects of folic acid and creatine supplementation on arsenic methylation in a randomized controlled trial of Bangladeshi adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Maiti, A.; Karmakar, S.; Das, A.S.; Mukherjee, M.; Nanda, A.; Mitra, C. Folic acid or combination of folic acid and vitamin B(12) prevents short-term arsenic trioxide-induced systemic and mitochondrial dysfunction and DNA damage. Environ. Toxicol. 2009, 24, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Dey, A.; Perveen, H.; Dolai, D. Involvement of metallothionein, homocysteine and B-vitamins in the attenuation of arsenic-induced uterine disorders in response to the oral application of hydro-ethanolic extract of Moringa oleifera seed: A preliminary study. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozack, A.K.; Saxena, R.; Gamble, M.V. Nutritional Influences on One-Carbon Metabolism: Effects on Arsenic Methylation and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 401–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B.A.; Hall, M.N.; Liu, X.; Parvez, F.; Sanchez, T.R.; van Geen, A.; Mey, J.L.; Siddique, A.B.; Shahriar, H.; Uddin, M.N.; et al. Folic Acid and Creatine as Therapeutic Approaches to Lower Blood Arsenic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.N.; Howe, C.G.; Liu, X.; Caudill, M.A.; Malysheva, O.; Ilievski, V.; Lomax-Luu, A.M.; Parvez, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shahriar, H.; et al. Supplementation with Folic Acid, but Not Creatine, Increases Plasma Betaine, Decreases Plasma Dimethylglycine, and Prevents a Decrease in Plasma Choline in Arsenic-Exposed Bangladeshi Adults. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordas, K.; Lönnerdal, B.; Stoltzfus, R.J. Interactions between nutrition and environmental exposures: Effects on health outcomes in women and children. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2794–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, Y.S.; Ramalaksmi, B.A.; Kumar, B.D. Lead and trace element levels in placenta, maternal and cord blood: A cross-sectional pilot study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2014, 40, 2184–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, C.C.; Zalups, R.K. Molecular and ionic mimicry and the transport of toxic metals. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 204, 274–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F. Zinc and multi-mineral supplementation should mitigate the pathogenic impact of cadmium exposure. Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, M.; Perveen, H.; Dash, M.; Jana, S.; Khatun, S.; Dey, A.; Mandal, A.K.; Chattopadhyay, S. Arjunolic Acid Improves the Serum Level of Vitamin B(12) and Folate in the Process of the Attenuation of Arsenic Induced Uterine Oxidative Stress. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 182, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.C.; Douillet, C.; Dover, E.N.; Stýblo, M. Prenatal arsenic exposure and dietary folate and methylcobalamin supplementation alter the metabolic phenotype of C57BL/6J mice in a sex-specific manner. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, J.E.; Ilievski, V.; Richardson, D.B.; Herring, A.H.; Stýblo, M.; Rubio-Andrade, M.; Garcia-Vargas, G.; Gamble, M.V.; Fry, R.C. Maternal one carbon metabolism and arsenic methylation in a pregnancy cohort in Mexico. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Gamble, M.; Slavkovich, V.; Liu, X.; Levy, D.; Cheng, Z.; van Geen, A.; Yunus, M.; Rahman, M.; Pilsner, J.R.; et al. Determinants of arsenic metabolism: Blood arsenic metabolites, plasma folate, cobalamin, and homocysteine concentrations in maternal-newborn pairs. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Fowler, B.A. Roles of biomarkers in evaluating interactions among mixtures of lead, cadmium and arsenic. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008, 233, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupsco, A.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A.; Just, A.C.; Amarasiriwardena, C.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Cantoral, A.; Sanders, A.P.; Braun, J.M.; Svensson, K.; Brennan, K.J.M.; et al. Prenatal Metal Concentrations and Childhood Cardiometabolic Risk Using Bayesian Kernel Machine Regression to Assess Mixture and Interaction Effects. Epidemiology 2019, 30, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah-Kulkarni, S.; Lee, S.; Jeong, K.S.; Hong, Y.C.; Park, H.; Ha, M.; Kim, Y.; Ha, E.H. Prenatal exposure to mixtures of heavy metals and neurodevelopment in infants at 6 months. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 109122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, C.; Amaya, E.; Gil, F.; Fernández, M.F.; Murcia, M.; Llop, S.; Andiarena, A.; Aurrekoetxea, J.; Bustamante, M.; Guxens, M.; et al. Prenatal co-exposure to neurotoxic metals and neurodevelopment in preschool children: The Environment and Childhood (INMA) Project. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyanwu, B.O.; Ezejiofor, A.N.; Igweze, Z.N.; Orisakwe, O.E. Heavy Metal Mixture Exposure and Effects in Developing Nations: An Update. Toxics 2018, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsyth, J.E.; Saiful Islam, M.; Parvez, S.M.; Raqib, R.; Sajjadur Rahman, M.; Marie Muehe, E.; Fendorf, S.; Luby, S.P. Prevalence of elevated blood lead levels among pregnant women and sources of lead exposure in rural Bangladesh: A case control study. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Specimen Type and Timing | Control Variables Adjusted | Association with PTB Odds Ratio or Relative Risk (95% CI), p Value | Qualitative Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cantonwine et al., 2010 [21] | Mexico | Cohort | n = 235 | Maternal blood at 2nd trimester | Maternal age, education, prior adverse birth outcome, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, infant sex | Mean ± SD: 6.3 ± 4.3 μg/dL OR, 95% CI for one SD increase in Pb: 1.75, 1.02 to 3.02 | 8 |

| Ahamed et al., 2009 [34] | India | Case-control | n = 60 | Placental tissue | - | Term vs. Preterm Mean ± SD: 0.27 ± 0.15 μg/g vs. 0.39 ± 0.2 μg/g; p < 0.05 | 7 |

| Berkowitz et al., 2006 [22] | USA | Ecological | n = 169,878 | Pb level in air | Maternal age, infant’s sex, birth order, prior stillbirth | No significant association | - |

| Cheng et al.,2017 [23] | China | Cohort | n = 7299 | Maternal urine before delivery | Maternal age, occupation, BMI, parity, passive smoking, pregnancy-induced hypertension, urinary concentration of cadmium and arsenic. | Pb concentration in Tercile2 (2.29–4.06 µg/g Cr): AOR, 95% CI: 1.43, 1.07 to 1.89 Tercile3 (>4.06 µg/g Cr): AOR, 95% CI: 1.96, 1.31 to 2.44, p < 0.01 | 8 |

| El Sawi et al., 2013 [35] | Egypt | Cohort | n = 100 | Cord blood | - | Mean ± SD 8.77 µg/dL ± 4.03. High Pb group (≥10 µg/dL−1) vs. Low Pb grp (<10g/dL−1), 33.3% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001 | 6 |

| Falcon et al., 2003 [36] | Spain | Cross-sectional | n = 89 | Placental tissue | - | Term vs. PTB Mean ± SD Pb (ng/g) 103.2 ± 49.5 vs. 153.9± 71.7, p = 0.004 | 7 |

| Freire et al., 2019 [24] | Spain | Cohort | n = 327 | Placental tissue | Education, newborn sex, level of other metals (As, Cd, Mn, Cr) | No significant association | 8 |

| Irwinda et al., 2019 [37] | Indonesia | Cross-sectional | n = 51 | Maternal blood, placental tissues and cord blood at delivery | - | Term vs. PTB: Placenta (ng/g): 0.02 (0.01) vs. 0.81 (1.43), p: 0.009 Maternal serum and cord blood (µg/dL): No significant association | 7 |

| Jelliffe et al., 2006 [25] | USA | Cohort | n = 262 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Low birth weight, race, insurance, maternal age, parity, infant sex | Pb level of <10 µg/dL vs. ≥10 µg/dL: AOR, 95% CI: 3.2, 1.2 to 7.4, p < 0.05 | 9 |

| Li et al., 2017 [26] | China | Cohort | n = 3125 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Pre pregnancy BMI, maternal age, time of serum collection, gravidity, parity, and monthly income. | Medium-Pb grp (1.18–1.70 µg/dL): AOR, 95% CI: 2.33, 1.49 to 3.65 High-Pb grp (>1.71 µg/dL): AOR, 95% CI: 3.09, 2.01 to 4.76 | 8 |

| Ozsoy et al., 2012 [38] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | n = 810 | Meconium collected at birth | - | Median (min–max) (ng/g/Kg) in Term vs. PTB known etiology:10.2 (4.6–27.1) vs. 15.5 (5.8–43.2), p < 0.001 | 8 |

| Perkins et al., 2014 [27] | USA | Cohort | n = 949 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, income, maternal serum zinc concentration, gravidity and parity | Mean 1.2 µg/dL (range, 0.0–5.0) Highest vs. lowest quartile: OR, 95% CI: 1.85, 0.79 to 4.34 | 9 |

| Rabito et al., 2014 [39] | USA | Cohort | n = 98 | Maternal blood during second and third trimester of pregnancy | - | Geometric mean (range) (µg/dL): 2nd trimester: 0.43 (0.19–1.22) 3rd trimester: 0.43 (0.19–2.10) OR, 95% CI for 0.1 unit increase 2nd trimester: 1.66, 1.23 to 2.23, p < 0.01 3rd trimester: 1.24, 1.01 to 1.52, p < 0.05 | 8 |

| Taylor et al., 2015 [28] | UK | Cohort | n = 4285 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Maternal height, smoking, parity, infant sex and gestational age. | Mean: 3.67 ± 1.47 µg/dL. <5 vs. ≥5 µg/dL: AOR, 95% CI 2.00, 1.35 to 3.00 | 8 |

| Tsuji et al., 2018 [29] | Japan | Cohort | n = 14,847 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking, partner smoking, drinking habits, gravidity, parity, the number of cesarean sections, uterine infection, household income, educational levels, and sex of infant | No significant association | 8 |

| Vigeh et al., 2011 [30] | Iran | Cohort | n = 348 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Maternal age, infant sex, education, passive smoking, pregnancy weight gain, parity, hematocrit and type of delivery | PTB vs. Term, means ± SD: 4.46 ± 1.86 vs. 3.43 ± 1.22 mg/dL, p < 0.05 OR, 95% CI:1.41, 1.08 to 1.84 | 8 |

| Wai et al., 2017 [31] | Myanmar | Cohort | n = 419 | Maternal urine during pregnancy. | Maternal age, education, infant sex, smoking, gestational age, primigravida and antenatal visits | No significant association | 7 |

| Yildirim et al., 2019 [40] | Turkey | Case-control | n = 50 | Maternal blood and urine, amniotic fluid and cord blood | - | Term vs. PTB: Pb concentration (μg/L) Mother urine: 2.62 (1.07–3.35) vs. 1.83 (1.08–3.14), p < 0.001 Maternal blood, cord blood, amnion fluid: No significant association | 7 |

| Zhang et al., 2015 [32] | China | Case-control | n = 408 | Maternal urine | Gestational age, income, maternal BMI, parity, passive smoking, and hypertension during pregnancy. | Highest tertile (≥11.67 µg/g) vs. lowest tertile (<5.41μg/g): AOR, 95% CI: 2.96, 1.49–5.87 | 6 |

| Zhu et al., 2010 [33] | USA | Retrospective cohort | n = 43,288 | Maternal blood before delivery | Maternal age, gestational age, parity, race, ethnicity, education, smoking, alcohol drinking, drug abuse, in wedlock, participation in special financial assistant program, timing of lead test, and infant sex | Mean: 2.1 µg/dL No significant association between quartiles | 5 |

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Specimen Type and Timing | Control Variables Adjusted | Association with PTB Odds Ratio or Relative Risk (95% CI), p Value | Qualitative Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al., 2014 [41] | USA | Cohort | n = 50 | Maternal blood and cord blood at delivery | - | Term vs. PTB: Mean (95% CI) Mother’s plasma (µg/L): 0.55 (0.48–0.63) vs. 0.93 (0.78–1.10), p = 0.0002 Mother RBC (µg/L): 1.37 (1.21–1.55) vs. 1.86 (1.49–2.33), p = 0.026 Cord plasma (µg/L): 0.46 (0.40–0.53) vs. 0.83 (0.73–0.94), p = 0.0024 Cord RBC (µg/L): 1.65 (1.46–1.86) vs. 2.22 (1.67–2.96), p = 0.039 | 5 |

| Bashore et al., 2014 [42] | USA | Cohort | n = 159 | Urine at pregnancy, cord blood | Maternal age and race | No significant association | 7 |

| Burch et al., 2014 [43] | USA | Ecological | n = 362,625 | Hg level in fish | Mother’s age, education, race, smoking, previous live births and stillborn | OR, 95% CI For African American: 2nd quartile (>0.17–0.29 ppm): 1.14, 1.08 to 1.21 3rd quartile (>0.29–0.62 ppm): 1.18, 1.11 to 1.25 4th quartile (>0.62 ppm): 1.10, 1.04 to 1.17 For European American: 2nd quartile (>0.17–0.29 ppm): 1.06, 1.02 to 1.11 3rd quartile and 4th quartile: No significant association | - |

| Freire et al., 2019 [24] | Spain | Cohort | n = 327 | Placental tissue | Maternal education, infant sex, level of other metals (As, Pb, Cd, Mn, Cr), | No significant association | 8 |

| Irwinda et al., 2019 [37] | Indonesia | Cross-sectional | n = 51 | Maternal blood, placental tissues and cord blood at delivery | - | Term vs. PTB: Placental Hg level (ng/g): 0.20 (0.17) vs. 20.47 (41.35), p = 0.019 Serum and Cord blood Hg levels (µg/L): No significant association | 7 |

| Tsuji et al., 2018 [29] | Japan | Cohort | n = 14,847 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking, partner, drinking, gravidity, parity, the number of cesarean sections, uterine infection, income, educational levels, and sex of infant | No significant association | 8 |

| Yildirim et al., 2019 [40] | Turkey | Case-control | n = 50 | Maternal blood and urine, amniotic fluid, cord blood | - | No significant association | 7 |

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Specimen Type and Timing | Control Variables Adjusted | Association with PTB Odds Ratio/Relative Risk (95% CI), p Value | Qualitative Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freire et al., 2019 [24] | Spain | Cohort | n = 327 | Placental tissue | Maternal education, infant sex, level of other metals (Pb, As, Mn, Cr), | Median (25th and 75th percentiles) (ng/g): 4.452 (2.786–6.487) OR, 95% CI for each 10% increase of Cd: 0.92, 0.84 to 0.99 | 8 |

| Huang et al., 2017 [45] | China | Case-control | n = 408 | Urine during pregnancy | Maternal education, household income, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity and passive smoking during pregnancy | Median (range) (μg/g) Cases: 0.60, (<0.01–5.61) Controls: 0.48 (0.04–18.09) Preterm low birth weight: OR, 95% CI Medium (0.35–0.70): 1.75, 0.88 to 3.47 High (≥0.70): 2.51, 1.24 to 5.07 | 6 |

| Johnston et al., 2014 [46] | USA | Cohort | n = 1027 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Maternal age, education, race, insurance, parity, history of anxiety, cotinine defined smoking status, and infant sex | Mean ± SD (mg/L): 0.46 ± 0.34 OR, 95% CI for one SD increase of Cd Medium (0.29–0.49 µg/L):1.24, 0.81 to 1.89 High (≥0.50 µg/L): 1.17, 0.74 to 1.87 | 6 |

| Ozsoy et al., 2012 [38] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | n = 810 | Meconium | - | Median (min-max) (ng/g/Kg) in Term vs. PTB Known etiology: 0.78 (0.28–2.57) vs. 1.31 (0.48–5.03), p ≤ 0.001 | 8 |

| Tsuji et al., 2018 [29] | Japan | Cohort | n = 14,847 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | Pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking, partner smoking, drinking, gravidity, parity, the number of cesarean sections, uterine infection, household income, education, and infant sex | Median (ng/g) (25th and 75th percentiles) Early preterm = 0.79 (0.57,1.18) Late preterm = 0.71 (0.51,0.98) Term = 0.66 (0.50, 0.90), p = 0.014 | 8 |

| Wai et al., 2017 [31] | Myanmar | Cohort | n = 419 | Maternal urine during pregnancy | Maternal age, education, infant sex, smoking status, gestational age, primigravida and antenatal visits | Median (IQR): 0.86 (0.50–1.40) µg/g creatinine AOR, 95% CI for one unit increase of Cd: 1.05, 0.97 to1.13 | 7 |

| Wang et al., 2016 [47] | China | Cohort | n = 3254 | Maternal blood during pregnancy | pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal age, income, parity, gravidity and serum zinc level | Mean (range) (mg/L): 0.89 (0.04–8.08) Medium (0.65 to 0.94 mg/L) serum Cd: No significant association High serum Cd level (≥0.95 mg/L) AOR, 95% CI: 3.02, 2.02 to 4.50; p < 0.001 | 8 |

| Yang et al., 2016 [48] | China | Cohort | n = 5364 | Maternal urine before delivery | Maternal age, education, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, passive smoking, net weight gain during pregnancy, infant sex, other metals (arsenic, lead) | Geometric mean (range) μg/g creatinine: 0.55 (0.01–2.85) AOR, 95% CI for each ln-unit increase in urinary Cd: 1.78, 1.45 to 2.19 | 9 |

| Yildirim et al., 2019 [40] | Turkey | Case-control | n = 50 | Maternal blood, urine, amniotic fluid and cord blood | - | No significant association | 7 |

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Specimen Type and Timing | Control Variables Adjusted | Association with PTB Odds Ratio/Relative Risk (95% CI), p Value | Qualitative Assessment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad et al. 2001 [49] | Bangladesh | Cross-Sectional | n = 192 | Tube well water | Maternal age, education, age at marriage, SES | Mean As levels: High exposure group: 0.240 mg/L Low exposure group: ≤0.02 mg/L High exposure vs. low exposure: 122.2 vs. 47.8, p value 0.018 | 7 |

| Almberg et al. 2017 [50] | USA | Ecological | n = 428,804 | Drinking water | Maternal age, education, marital status, parity, race/ethnicity, smoking, pre-pregnancy BMI, infant sex, Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) supplemental nutrition program, | AOR, 95% CI for1 μg/L increase in As in drinking water for counties with: a Well restriction <10:1.10, 1.06 to 1.15 b Well restriction <20: 1.08, 1.02 to 1.14 | - |

| Banu et al. 2013 [51] | Bangladesh | Ecological | n = 321 | Tube well water | Maternal age, education, weight gain during pregnancy, environmental tobacco smoke, pregnancy history, and spouse’s education | No significant association | - |

| Freire et al. 2019 [24] | Spain | Cohort | n = 327 | Placental tissue | Maternal education, infant sex, cohort (random effect), all other metals. | No significant association | 8 |

| Myers et al. 2010 [52] | China | Cross-Sectional | n = 9890 | Well water | Adequacy of prenatal care utilization | No significant association | 7 |

| Rahman et al. 2018 [53] | Bangladesh | Cohort | n = 1183 | Tube well water and toenail samples | Maternal age, education, enrollment BMI, number of past pregnancies, passive smoking, and water arsenic exposure. | Median (range) As levels for drinking water (µg/L): 2·2 (<LOD–1400) Toenail samples (µg/g): 1.2 (<LOD–46.6) RR, 95% CI for one unit increase in natural log As For drinking water: 1.12, 1.07 to 1.17 For toenail: 1.13, 1.03 to 1.24 | 9 |

| Shi et al. 2015 [54] | USA | Ecological | n = 177,995 | Ground water | - | PTB when arsenic level >10 µg/L: r = 0.70 | - |

| Wai et al. 2017 [31] | Myanmar | Cohort | n = 419 | Maternal urine during pregnancy | Maternal age, education, infant sex, smoking, gestational age, primigravida and antenatal visits | Median (IQR): 74 (45–127) µg/g creatinine AOR, 95% CI for one unit increase of As: 1.00, 0.99 to1.00 | 7 |

| Wang et al. 2018 [55] | China | Cohort | n = 3194 | Maternal blood | Pre-pregnancy BMI | Mean, median (range) (µg/L): 5.10, 4.87 (0.02 to 43.52) High As group (>6.68 μg/L) OR, 95% CI: 1.47, 1.03 to 2.09, p = 0.034 | 6 |

| Yang et al. 2003 [56] | Taiwan | Ecological | n = 18,259 | Well water | Maternal age, education, marital status, and infant sex | No significant association | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khanam, R.; Kumar, I.; Oladapo-Shittu, O.; Twose, C.; Islam, A.A.; Biswal, S.S.; Raqib, R.; Baqui, A.H. Prenatal Environmental Metal Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020573

Khanam R, Kumar I, Oladapo-Shittu O, Twose C, Islam AA, Biswal SS, Raqib R, Baqui AH. Prenatal Environmental Metal Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020573

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhanam, Rasheda, Ishaan Kumar, Opeyemi Oladapo-Shittu, Claire Twose, ASMD Ashraful Islam, Shyam S. Biswal, Rubhana Raqib, and Abdullah H. Baqui. 2021. "Prenatal Environmental Metal Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020573

APA StyleKhanam, R., Kumar, I., Oladapo-Shittu, O., Twose, C., Islam, A. A., Biswal, S. S., Raqib, R., & Baqui, A. H. (2021). Prenatal Environmental Metal Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020573