Social Inclusion and Physical Activity in Ciclovía Recreativa Programs in Latin America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings

2.2. Characteristics of the Ciclovía Recreativa Programs

2.2.1. Bogotá: Ciclovía

2.2.2. Mexico City: Muévete en Bici (MEB)

2.2.3. Santiago de Cali: Ciclovida

2.2.4. Santiago de Chile: CicloRecreoVía

2.3. The Ciclovía Recreativa Program Surveys

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.3.2. Health Characteristics

2.3.3. Physical Activity Behaviors

2.3.4. Program Use

2.3.5. Participants’ Perceptions

2.4. Urban Segregation

2.4.1. Urban Segregation Index

2.4.2. Participants’ Trajectories Through the Ciclovía Program

2.4.3. Average SES per Traveled Kilometer

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Health Characteristics

3.3. Physical Activity Behaviors

3.4. Program Use

3.5. Participants’ Perceptions

3.6. Multi-Level Associations with Meeting Physical Activity Recommendations and Time Participants Spent in the Program

3.7. Urban Segregation Index

3.8. Participants’ Trajectories Through the Ciclovía Program

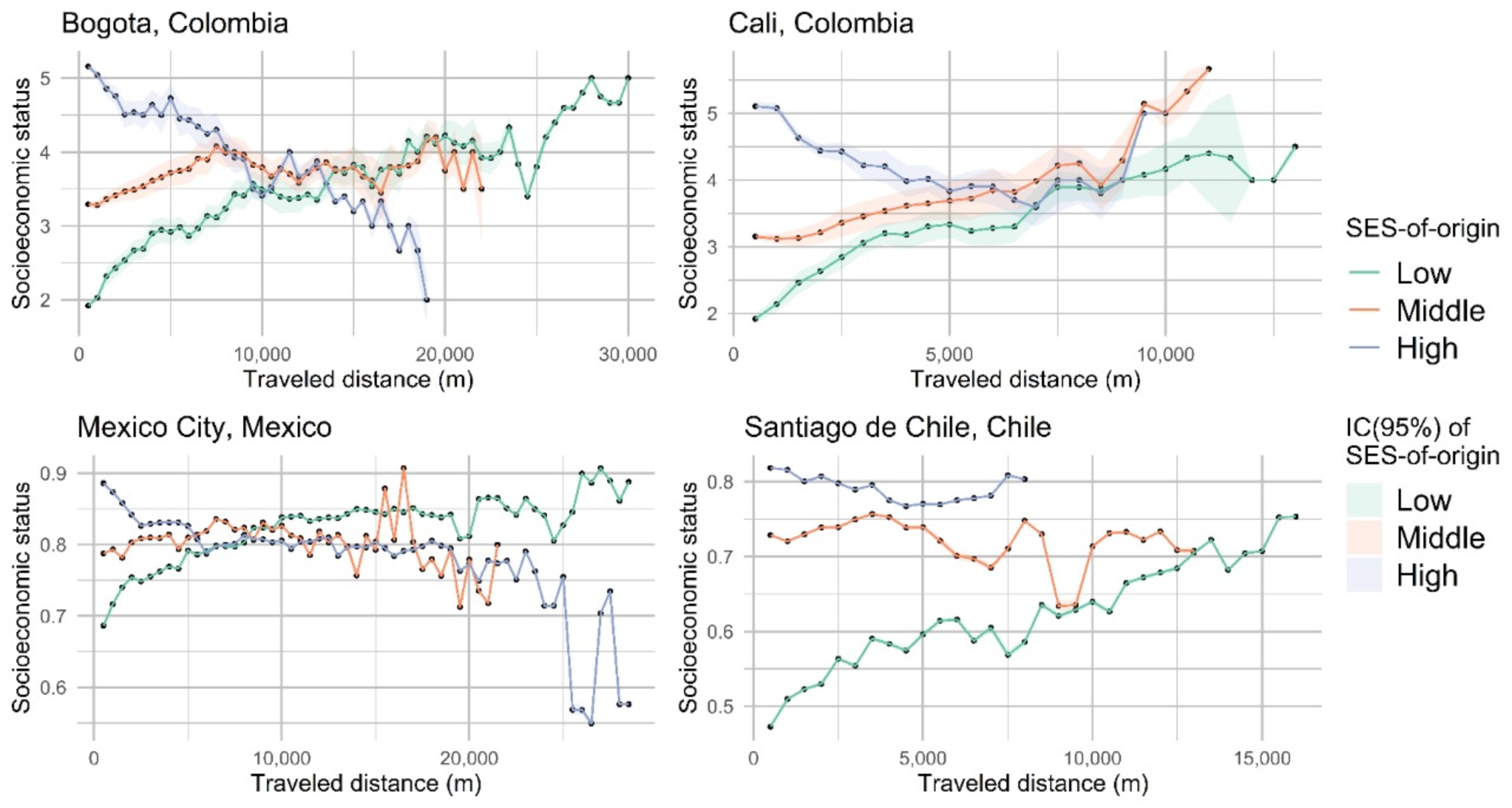

3.9. Average SES per Traveled Kilometer

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Foster, S.; Lowe, M.; Sallis, J.F.; Stevenson, M.; et al. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Slesinski, S.C.; Alazraqui, M.; Caiaffa, W.T.; Frenz, P.; Jordán Fuchs, R.; Miranda, J.J.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Dueñas, O.L.S.; Siri, J.; et al. A Novel International Partnership for Actionable Evidence on Urban Health in Latin America: LAC-Urban Health and SALURBAL. Glob. Chall. 2019, 3, 1800013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. The World’s Cities in 2018: Data Booklet; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9789211483062. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F. The Social Spatial Segregation in the Cities of Latin America; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corvalan, A.; Vargas, M. Segregation and conflict: An empirical analysis. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 116, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.A.; Bocarejo, J.P. Urban form and spatial urban equity in Bogota, Colombia. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4491–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkkonen, P.; Comandon, A.; Montejano Escamilla, J.A.; Guerra, E. Urban sprawl and the growing geographic scale of segregation in Mexico, 1990–2010. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ferranti, D.; Perry, G.; Ferreira, F.; Walton, M. Inequality in Latin America: Breaking with History? The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Habitat III Regional Report—Latin America and the Caribbean—Sustainable Cities with Equality; United Nations: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 9789211333930. [Google Scholar]

- Galván, M.; Amarante, V.; Mancero, X. Inequality in Latin America: A global measurement. CEPAL Rev. 2016, 2016, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO. World Social Science Report 2016, Challenging Inequalities: Pathways to a Just World; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Tagle, J. La persistencia de la segregación y la desigualdad en barrios socialmente diversos: Un estudio de caso en La Florida, Santiago. Eure 2016, 42, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borsdorf, A.; Hildalgo, R.; Vidal-Koppmann, S. Social segregation and gated communities in Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires. A comparison. Habitat Int. 2016, 54, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabatini, F.; Jordan, R.; Simioni, D. Direcciones para el Futuro; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini, F.; Wormald, G.; Rasse, A.; Trebilcock, M. Disposición al encuentro con el otro social en las ciudades chilenas: Resultados de investigación e implicancias prácticas. In Cultura de Cohesión e Integración Social en Ciudades Chilenas; Trebilcock, Ed.; Revista INVI: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2013; pp. 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- López-Morales, E. A multidimensional approach to urban entrepreneurialism, financialization, and gentrification in the highrise residential market of inner Santiago, Chile. Res. Polit. Econ. 2016, 31, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sabatini, F.; Cáceres, G.; Cerda, J. Segregación residencial en las principales ciudades chilenas: Tendencias de las tres últimas décadas y posibles cursos de acción. EURE 2001, 27, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.; Mora, R. Las autopistas urbanas concesionadas: Una nueva forma de segregación. ARQ 2005, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasse, A. Juntos pero no revueltos. Procesos de integración social en fronteras residenciales entre hogares de distinto nivel socioeconómico. EURE 2015, 41, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoschka, M. El nuevo modelo de la ciudad latinoamericana: Fragmentación y privatización. EURE 2002, 28, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, S. Close but Divided: How Walls, Fences and Barriers Exacerbate Social Differences and Foster Urban Social Group Segregation. Hous. Theory Soc. 2013, 30, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, I.G. Is Segregation Bad for Your Health? The Case of Low Birth Weight. Brook.-Whart. Pap. Urban Aff. 2000, 2000, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- States, T.H.E.U.; Hendren, N.; Friedman, J.; Heckman, J.; Hilger, N.; Hornbeck, R.; Katz, L.; Lalumia, S.; Looney, A.; Mitnik, P.; et al. Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the united states. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 1553–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurson, K. Social Mix, Reputation and Stigma: Exploring Residents’ Perspectives of Neighbourhood Effects. In Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 101–119. ISBN 9789400723092. [Google Scholar]

- Been, V.; Ellen, I.; Madar, J. The High Cost of Segregation: Exploring Racial Disparities in High-Cost Lending. Fordham Urban Law J. 2008, 36, 361–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bezin, E.; Moizeau, F. Cultural dynamics, social mobility and urban segregation. J. Urban Econ. 2017, 99, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, R.; Greene, M.; Corado, M. Implicancias en la actividad física y la salud del Programa CicloRecreoVía en Chile. Rev. Med. Chil. 2018, 146, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romero, H.; Vásquez, A.; Fuentes, C.; Salgado, M.; Schmidt, A.; Banzhaf, E. Assessing urban environmental segregation (UES). The case of Santiago de Chile. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 23, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L. From “streets for traffic” to “streets for people”: Can street experiments transform urban mobility? Transp. Rev. 2020, 40, 734–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, O.L.; Díaz del Castillo, A.; Triana, C.A.; Acevedo, M.J.; Gonzalez, S.A.; Pratt, M. Reclaiming the streets for people: Insights from Ciclovías Recreativas in Latin America. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2017, 103, S34–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisel, J.D.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Montes, F.; Martinez, E.O.; Lemoine, P.D.; Valdivia, J.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Zarama, R. Network Analysis of Bogotá’s Ciclovía Recreativa, a Self-Organized Multisectorial Community Program to Promote Physical Activity in a Middle-Income Country. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, e127–e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sarmiento, O.L.; Pedraza, C.; Triana, C.A.; Díaz, D.P.; González, S.A.; Montero, S. Promotion of Recreational Walking: Case Study of the Ciclovía-Recreativa of Bogotá. In Walking: Connecting Sustainable Transport with Health (Transport and Sustainability); Mulley, C., Gele, K., Ding, D., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bradford, West Yorkshire, UK, 2017; pp. 275–286. ISBN 978-1-78714-628-0. [Google Scholar]

- Salvo, D.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Reis, R.S.; Hino, A.A.F.; Bolivar, M.A.; Lemoine, P.D.; Gonçalves, P.B.; Pratt, M. Where Latin Americans are physically active, and why does it matter? Findings from the IPEN-adult study in Bogota, Colombia; Cuernavaca, Mexico; and Curitiba, Brazil. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2017, 103, S27–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Romero-Martinez, M.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Barquera, S.; Janssen, I. Move on Bikes Program: A Community-Based Physical Activity Strategy in Mexico City. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gómez, L.F.; Mosquera, J.; Gómez, O.L.; Moreno, J.; Pinzon, J.D.; Jacoby, E.; Cepeda, M.; Parra, D.C. Social conditions and urban environment associated with participation in the Ciclovia program among adults from Cali, Colombia. Cad. Saude Publica 2015, 31, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Torres, A.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Stauber, C.; Zarama, R. The Ciclovia and Cicloruta Programs: Promising Interventions to Promote Physical Activity and Social Capital in Bogotá, Colombia. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e23–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, C.A.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Bravo-Balado, A.; González, S.A.; Bolívar, M.A.; Lemoine, P.; Meisel, J.D.; Grijalba, C.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Active streets for children: The case of the Bogotá Ciclovía. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0207791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarmiento, O.L.; Behrentz, E.; Caycedo, F.C. La ciclovía, un espacio sin ruido y sin contaminación. Nota Uniandina 2008, 8, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, S.; Batteate, C.; Cole, B.; Froines, J.; Zhu, Y. Air quality impacts of a CicLAvia event in Downtown Los Angeles, CA. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, O.L.; Schmid, T.L.; Parra, D.C.; Díaz-del-Castillo, A.; Gómez, L.F.; Pratt, M.; Jacoby, E.; Pinzón, J.D.; Duperly, J. Quality of life, physical activity, and built environment characteristics among colombian adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7 (Suppl. 2), S181–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parra, D.C.; Adlakha, D.; Pinzon, J.D.; Van Zandt, A.; Brownson, R.C.; Gomez, L.F. Geographic Distribution of the Ciclovia and Recreovia Programs by Neighborhood SES in Bogotá: How Unequal is the Geographic Access Assessed Via Distance-based Measures? J. Urban Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, A.B.; Marlier, E. Analysing and Measuring Social Inclusion in a Global Context; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9789211302868. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Wang, D. Measuring urban segregation based on individuals’ daily activity patterns: A multidimensional approach. Environ. Plan. A 2017, 49, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDRD Ciclovía Bogotana. Available online: https://www.idrd.gov.co/ciclovia-bogotana# (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- IDRD Reporte de la Ciclovía. Available online: https://www.idrd.gov.co/reporte-la-ciclovia (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Gobierno de la Ciudad de México Muévete en Bici. Available online: http://data.sedema.cdmx.gob.mx/mueveteenbici/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=44:mueveteenbici&catid=35:muevetebici&Itemid=34 (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Alcadía de Santiago de Cali Ciclovida Cali. Available online: https://www.cali.gov.co/deportes/publicaciones/111083/ciclovida_cali/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Camargo, D.M.; Ramírez, P.C.; Quiroga, V.; Ríos, P.; Férmino, R.C.; Sarmiento, O.L. Physical activity in public parks of high and low socioeconomic status in Colombia using observational methods. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finley, R.; Finley, C. SurveyMonkey Inc. Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 11 August 2020).

- Quistberg, D.A.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Bilal, U.; Moore, K.; Ortigoza, A.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Frenz, P.; Friche, A.A.; Caiaffa, W.T.; et al. Building a Data Platform for Cross-Country Urban Health Studies: The SALURBAL Study. J. Urban Health 2019, 96, 311–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística Estratificación Socioeconómica para Servicios Públicos Domiciliarios. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/servicios-al-ciudadano/servicios-informacion/estratificacion-socioeconomica#preguntas-frecuentes (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- INEGI Mapas. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/datos/?t=0150 (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Adimark Mapa Socioeconómico de Chile. Available online: http://www.comunicacionypobreza.cl/publication/mapa-socioeconomico-de-chile-2004/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Encinas, F.; Truffello, R.; Aguirre, C.; Hidalgo, R. Especulación, renta de suelo y ciudad neoliberal. O por qué con el libre mercado no basta. ARQ 2019, 2019, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio de Ciudades UC Índice Socio Material Territorial (ISMT). Available online: https://ideocuc-ocuc.hub.arcgis.com/datasets/97ae30fe071349e89d9d5ebd5dfa2aec_0 (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- World Health Organization Body Mass Index—BMI. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Available online: https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/library/materials/international-physical-activity-questionnaire-ipaq (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Armstrong, T.; Bull, F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J. Public Health (Bangkok) 2006, 14, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Jacoby, E.; Gomez, L.F.; Neiman, A. Influences of built environments on walking and cycling: Lessons from Bogotá. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2009, 3, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.C.; Gomez, L.F.; Parra, D.C.; Lobelo, F.; Mosquera, J.; Florindo, A.A.; Reis, R.S.; Pratt, M.; Sarmiento, O.L. Lessons learned after 10 years of IPAQ use in Brazil and Colombia. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bull, F.C.; Maslin, T.S.; Armstrong, T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): Nine country reliability and validity study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C. Advances in Research Methods for the Study of Urban Segregation. In Urban Segregation and Governance in the Americas; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 21–35. ISBN 9780230620841. [Google Scholar]

- Louf, R.; Barthelemy, M. Patterns of Residential Segregation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Apparicio, P.; Martori, J.C.; Pearson, A.L.; Fournier, É.; Apparicio, D. An Open-Source Software for Calculating Indices of Urban Residential Segregation. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2014, 32, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Soc. Forces 1988, 67, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iceland, J. The Multigroup Entropy Index (also Known as Theil’s H or the Information Theory Index); U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Roberto, E. The Divergence Index: A Decomposable Measure of Segregation and Inequality. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.01167. [Google Scholar]

- Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad Portal de Geoinformación 2020. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/#secc0t3 (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Ortega Díaz, A. Assessment of the Different Measures of Poverty in Mexico: Relevance, Feasibility and Limits; ITESM-EGAP: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Bojesen Christensen, R.H.; Jensen, S.P. lmerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/lmerTest.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Rola, B. Promoting Social Integration. Glob. Soc. Policy An Interdiscip. J. Public Policy Soc. Dev. 2009, 9, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormald, G.; Flores, C.; Paz, M.; Rasse, A. Cohesive culture and integration in chilean cities. Rev. INVI 2012, 27, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DANE. Boletín Técnico Encuesta de Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana (ECSC) Periodo de Referencia año 2018; DANE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. XV Encuesta Nacional Urbana de Seguridad Ciudadana (ENUSC 2018)-Presentación de Resultados; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2019.

- Taylor, R.B.; Harrell, A.V. Physical Environment and Crime; U.S. Department of Justice-National Institute of Justice: Rockville, MD, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Neira, I.; Lacalle-Calderon, M.; Portela, M.; Perez-Trujillo, M. Social Capital Dimensions and Subjective Well-Being: A Quantile Approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 2551–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E.; Adams, I.; Kawachi, I. The development of a bridging social capital questionnaire for use in population health research. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chuang, Y.-C.; Chuang, K.-Y.; Yang, T.-H. Social cohesion matters in health. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kepper, M.M.; Myers, C.A.; Denstel, K.D.; Hunter, R.F.; Guan, W.; Broyles, S.T. The neighborhood social environment and physical activity: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I. Social Capital and Community Effects on Population and Individual Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 896, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.H.; Carlin, A.; Woods, C.; Nevill, A.; MacDonncha, C.; Ferguson, K.; Murphy, N. Active Students Are Healthier and Happier Than Their Inactive Peers: The Results of a Large Representative Cross-Sectional Study of University Students in Ireland. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richards, J.; Jiang, X.; Kelly, P.; Chau, J.; Bauman, A.; Ding, D. Don’t worry, be happy: Cross-sectional associations between physical activity and happiness in 15 European countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, D.A.S.; dos Silva, R.J.S. Association between physical activity level and consumption of fruit and vegetables among adolescents in northeast Brazil. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2015, 33, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Secretaria de Salud de Bogotá Cuídate, sé Feliz. Available online: http://www.saludcapital.gov.co/Paginas2/Cuidate_se_feliz.aspx (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Engelberg, J.K.; Carlson, J.A.; Black, M.L.; Ryan, S.; Sallis, J.F. Ciclovía participation and impacts in San Diego, CA: The first CicloSDias. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 2014, 69, S66–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mason, M.; Welch, S.B.; Becker, A.; Block, D.R.; Gomez, L.; Hernandez, A.; Suarez-Balcazar, Y. Ciclovìa in Chicago: A strategy for community development to improve public health. Community Dev. 2011, 42, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G. Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, by Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K. Can Tactical Urbanism Be a Tool for Equity? A Conversation with Mike Lydon and Tony Garcia. Available online: https://usa.streetsblog.org/2020/07/06/can-tactical-urbanism-be-a-tool-for-equity-a-conversation-with-mike-lydon-and-tony-garcia/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- El Tiempo La bici Será el Pilar de la Nueva Movilidad en Bogotá, Tras Covid-19. Available online: https://www.eltiempo.com/bogota/coronavirus-en-bogota-como-le-esta-apostando-bogota-a-la-bicicleta-496376 (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Velázquez, C. Inauguran Ciclovía Temporal en Insurgentes sur. Día Internacional de la Bicicleta. Available online: https://www.milenio.com/politica/comunidad/cdmx-inauguran-ciclovia-temporal-insurgentes-sur#:~:text=¡Apedalear! (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Ortiz, J. Distanciamiento y Temor a Contagio: Recomiendan uso de Bicicletas y Aumento de Ciclovías en Chile. Available online: https://www.cedeus.cl/distanciamiento-y-temor-a-contagio-podria-traer-un-aumento-de-ciclovias-en-chile/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Dalton, A.M.; Jones, A.P.; Panter, J.; Ogilvie, D. Are GIS-modelled routes a useful proxy for the actual routes followed by commuters? J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenberg Raanan, M.; Shoval, N. Mental maps compared to actual spatial behavior using GPS data: A new method for investigating segregation in cities. Cities 2014, 36, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, N.M.; Forrest, R.; Xian, S. Exploring segregation and mobilities: Application of an activity tracking app on mobile phone. Cities 2016, 59, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.R.B.; Espenshade, T.J.; Bartumeus, F.; Chung, C.Y.; Ozgencil, N.E.; Li, K. New Approaches to Human Mobility: Using Mobile Phones for Demographic Research. Demography 2013, 50, 1105–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | Bogotá | Mexico City | Santiago de Cali | Santiago de Chile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Characteristic | ||||

| Population metrics | ||||

| Total population a | 7,878,783 | 8,918,653 | 2,470,852 | 7,112,808 |

| Population Density b | 21,916 | 11,247 | 17,691 | 9632 |

| Inequality metric | ||||

| GINI coefficient | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| Urban segregation metrics | ||||

| Entropy index (Mean ± SD) | 0.06 (0.13) | 0.11 (0.13) | 0.16 (0.17) | 0.82 (0.13) |

| Crime metric | ||||

| Homicide rate c | 14.30 | 16.00 | 51.30 | 4.90 |

| Urban landscape metrics | ||||

| Patch density d | 0.71 | 0.64 | 1.06 | 0.66 |

| Green area per capita e | 3.90 | 5.40 | 5.93 | 4.83 |

| Transportation metrics | ||||

| Motorization rate f | 247.00 | 544.05 | 251.28 | 254.67 |

| Urban travel delay index g | 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.34 |

| Ciclovía program characteristics | ||||

| Name | Ciclovía de Bogotá | Muévete En Bici | La Ciclovida de Cali | CicloRecreoVía |

| Year of inauguration | 1974 | 2007 | 1996 | 2006 |

| Length (Km) | 127.69 | 55 | 60 | 38 |

| Schedule | Su- Ho 7 h | Su 6 h | Su- Ho 5 h & Th 2 h | Su 4 h |

| Participants per event | 600,000–1,750,000 | 21,000 | 30,000 | 40,000 |

| Events per year | 66–72 | 37 | 93 | 51 |

| Source of funding | Public and Private | Public | Public | Public and Private |

| Program average cost per year (USD millions) h | 2.40 | 1.00 | 1.65 | 1.06 |

| Number of independent circuits | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9 |

| Scale | Metropolitan | Metropolitan | Metropolitan | Metropolitan |

| Percentage of the Ciclovía route in | ||||

| Low SES | 18.04 | 0 | 23.71 | 15.37 |

| Middle SES | 61.64 | 9.78 | 64.72 | 6.78 |

| High SES | 20.32 | 90.22 | 11.58 | 77.85 |

| Percentage of the Ciclovía route in | ||||

| Highly segregated geographical units | 66.03 | 27.29 | 21.18 | 61.54 |

| Segregated geographical units | 10.28 | 62.47 | 32.3 | 27.07 |

| Integrated geographical units | 11.67 | 10.24 | 25.97 | -- |

| Highly integrated geographical units | 12.02 | -- | 20.55 | 11.39 |

| Physical activity levels | ||||

| Meeting physical activity recommendations (%) i | 66.00 | 71.10 | 66.00 | 73.40% |

| Meeting physical activity recommendations (%) i, males | 61.20 | 74.50 | 61.20 | 75.60% |

| Meeting physical activity recommendations (%) i, females | 51.10 | 67.80 | 51.10 | 71.40% |

| Study Site | Origin Point | Destination Point |

|---|---|---|

| Bogotá | Participant’s home address or the nearest intersection to the participant’s home addresses. | The address of the place or the nearest intersection where participants were interviewed. |

| Mexico City | The nearest intersection to the place participants started their journey. | The destination point was the nearest intersection to the farthest point participants intended to reach during their journey. |

| Santiago de Cali | The nearest intersection to the participant’s home addresses. | The nearest intersection where participants were interviewed. |

| Santiago de Chile |

| Characteristic | Bogotá | Mexico City | Santiago de Cali | Santiago de Chile | Overall | Multi-Variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1001 | N = 721 | N = 1159 | N = 401 | N = 3282 | ||||||||||||

| n | % | * p-Value | n | % | * p-Value | n | % | * p-Value | n | % | * p-Value | n | % | * p-Value | * p-Value | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||||

| Male | 619 | 61.84% | <0.001 | 370 | 51.32% | 0.479 | 583 | 50.48% | 0.746 | 142 | 35.41% | <0.001 | 1714 | 52.29% | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Female | 382 | 38.16% | 351 | 48.68% | 572 | 49.52% | 259 | 64.59% | 1564 | 47.71% | ||||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 367 | 36.74% | <0.001 | 255 | 35.61% | <0.001 | 306 | 26.40% | <0.001 | 115 | 30.42% | <0.001 | 1043 | 32.07% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 30–49 | 451 | 45.15% | 334 | 46.65% | 522 | 45.04% | 181 | 47.88% | 1488 | 45.76% | ||||||

| ≥50 | 181 | 18.12% | 127 | 17.74% | 331 | 28.56% | 82 | 21.69% | 721 | 22.17% | ||||||

| Marital status a | ||||||||||||||||

| Single | 574 | 57.46% | <0.001 | 458 | 63.61% | <0.001 | 563 | 48.58% | 0.332 | -- | -- | -- | 1595 | 55.45% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Living with a partner | 425 | 42.54% | 262 | 36.39% | 596 | 51.42% | -- | -- | 1283 | 44.55% | ||||||

| Highest level of educational attainment | ||||||||||||||||

| Primary | 44 | 4.42% | <0.001 | 8 | 1.11% | <0.001 | 44 | 3.83% | <0.001 | 1 | 0.29% | <0.001 | 97 | 3.03% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Secondary/High school | 287 | 28.82% | 272 | 37.73% | 419 | 36.50% | 71 | 20.94% | 1049 | 32.74% | ||||||

| College//technical | 535 | 53.71% | 363 | 50.35% | 617 | 53.75% | 267 | 78.76% | 1782 | 55.65% | ||||||

| Master’s degree or higher | 130 | 13.05% | 78 | 10.82% | 68 | 5.92% | 0 | 0.00% | 276 | 8.61% | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 207 | 20.68% | <0.001 | 4 | 0.61% | <0.001 | 335 | 28.90% | <0.001 | 32 | 9.44% | <0.001 | 578 | 18.31% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 655 | 65.43% | 52 | 7.90% | 751 | 64.80% | 264 | 77.88% | 1722 | 54.55% | ||||||

| High | 139 | 13.89% | 602 | 91.49% | 73 | 6.30% | 43 | 12.68% | 857 | 27.15% | ||||||

| Car owner in household | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 458 | 45.75% | 0.007 | 202 | 36.66% | <0.001 | 703 | 60.81% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 1363 | 50.33% | 0.729 | <0.001 |

| No | 543 | 54.25% | 349 | 63.34% | 453 | 39.19% | -- | -- | 1345 | 49.67% | ||||||

| Health characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Perceived health status | ||||||||||||||||

| Excellent | 314 | 31.37% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 230 | 19.88% | <0.001 | 277 | 69.08% | <0.001 | 821 | 32.08% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Good | 588 | 58.74% | -- | -- | 760 | 65.69% | 104 | 25.94% | 1452 | 34.86% | ||||||

| Fair/Bad/Poor | 99 | 9.89% | -- | -- | 167 | 14.43% | 20 | 4.99% | 286 | 33.06% | ||||||

| Body Mass Index category b | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight | 20 | 2.00% | <0.001 | 4 | 0.55% | <0.001 | 11 | 0.95% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 35 | 1.21% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 644 | 64.34% | 352 | 48.82% | 511 | 44.09% | -- | -- | 1507 | 52.31% | ||||||

| Overweight | 297 | 29.67% | 270 | 37.45% | 469 | 40.47% | -- | -- | 1036 | 35.96% | ||||||

| Obese | 40 | 4.00% | 95 | 13.18% | 168 | 14.50% | -- | -- | 303 | 10.52% | ||||||

| Physical activity characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Meeting PA recommendations during the Ciclovía c | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 453 | 45.25% | 0.003 | 629 | 87.24% | <0.001 | 487 | 42.02% | <0.001 | 109 | 27.18% | <0.001 | 1678 | 51.13% | 0.197 | <0.001 |

| No | 548 | 54.75% | 92 | 12.76% | 672 | 57.98% | 292 | 72.82% | 1604 | 48.87% | ||||||

| Meeting weekly LTPA recommendations c,d | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 688 | 68.73% | <0.001 | 434 | 60.19% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1122 | 65.16% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| No | 313 | 31.27% | 287 | 39.81% | -- | -- | -- | -- | 600 | 34.84% | ||||||

| Meeting weekly overall PA recommendations (transportation or leisure) c | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 857 | 85.61% | <0.001 | 601 | 83.36% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1458 | 84.67% | <0.001 | 0.200 |

| No | 144 | 14.39% | 120 | 16.64% | -- | -- | -- | -- | 264 | 15.33% | ||||||

| Meeting PA recommendations (transport) c | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 524 | 52.35% | 0.137 | 353 | 48.96% | 0.576 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 877 | 50.93% | 0.441 | 0.165 |

| No | 477 | 47.65% | 368 | 51.04% | -- | -- | -- | -- | 845 | 49.07% | ||||||

| Program use characteristics | ||||||||||||||||

| Type of activity in the Ciclovía | ||||||||||||||||

| Cycling | 603 | 60.36% | <0.001 | 634 | 87.93% | <0.001 | 205 | 18.00% | <0.001 | 275 | 68.58% | <0.001 | 1717 | 52.67% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Rollerblading | 52 | 5.21% | 25 | 3.47% | 21 | 1.84% | 29 | 7.23% | 127 | 3.90% | ||||||

| Walking | 222 | 22.22% | 23 | 3.19% | 464 | 40.74% | 16 | 3.99% | 725 | 22.24% | ||||||

| Running/jogging | 118 | 11.81% | 38 | 5.27% | 163 | 14.31% | 73 | 18.20% | 392 | 12.02% | ||||||

| Other e | 4 | 0.40% | 1 | 0.14% | 286 | 25.11% | 8 | 2.00% | 299 | 9.17% | ||||||

| Time spent in the program (h) | ||||||||||||||||

| <3 h | 586 | 58.54% | <0.001 | 92 | 12.76% | <0.001 | 796 | 68.68% | <0.001 | 312 | 77.81% | <0.001 | 1786 | 54.42% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3–4 h | 210 | 20.98% | 279 | 38.70% | 231 | 19.93% | 62 | 15.46% | 782 | 23.83% | ||||||

| ≥4 h | 205 | 20.48% | 350 | 48.54% | 132 | 11.39% | 27 | 6.73% | 714 | 21.76% | ||||||

| Frequency of participation (Events) f | ||||||||||||||||

| At least once a year | 68 | 6.81% | <0.001 | 127 | 17.61% | <0.001 | 110 | 9.52% | <0.001 | 184 | 45.89% | <0.001 | 489 | 14.93% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Once per month | 120 | 12.01% | 95 | 13.18% | 105 | 9.09% | 59 | 14.71% | 379 | 11.57% | ||||||

| Two/Three times per month | 258 | 25.83% | 282 | 39.11% | 200 | 17.32% | 47 | 11.72% | 787 | 24.02% | ||||||

| ≥ 4 times per month | 553 | 55.36% | 217 | 30.10% | 740 | 64.07% | 111 | 27.68% | 1621 | 49.48% | ||||||

| People accompanied by at the program g | ||||||||||||||||

| Came alone | 567 | 56.64% | <0.001 | 473 | 65.69% | <0.001 | 763 | 65.83% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 1803 | 62.60% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Came with another person | 434 | 43.36% | 247 | 34.31% | 396 | 34.17% | -- | -- | 1077 | 37.40% | ||||||

| Reasons to attend the program | ||||||||||||||||

| Share with family/friends | 324 | 32.37% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 484 | 41.76% | <0.001 | 35 | 8.73% | <0.001 | 843 | 32.92% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Used for recreation/PA | 771 | 77.02% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 883 | 76.19% | <0.001 | 242 | 60.35% | <0.001 | 1896 | 74.03% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Health Benefits | 575 | 57.50% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 717 | 61.86% | <0.001 | 91 | 22.69% | <0.001 | 1383 | 54.02% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Other h | 144 | 14.40% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 213 | 18.38% | <0.001 | 133 | 33.17% | <0.001 | 490 | 19.14% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Activities if participants were not in the Ciclovía | ||||||||||||||||

| Stay at home | 93 | 9.36% | <0.001 | 149 | 21.07% | <0.001 | 276 | 24.30% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 518 | 18.26% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sedentary activity | 94 | 9.46% | 81 | 11.46% | 190 | 16.76% | -- | -- | 365 | 12.87% | ||||||

| Other type of physical activity | 701 | 70.52% | 477 | 67.47% | 644 | 56.69% | -- | -- | 1822 | 64.22% | ||||||

| Other i | 106 | 10.66% | -- | -- | 26 | 2.29% | -- | -- | 132 | 4.65% | ||||||

| Participants’ perceptions at the program | ||||||||||||||||

| Safety perception (crime) | ||||||||||||||||

| Unsafe | 37 | 3.70% | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | 494 | 42.62% | <0.001 | 22 | 5.49% | <0.001 | 553 | 21.60% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Safe | 915 | 91.50% | -- | -- | 383 | 33.05% | 379 | 94.51% | 1677 | 65.51% | ||||||

| Neither safe nor unsafe | 48 | 4.80% | -- | -- | 282 | 24.33% | -- | -- | 330 | 12.89% | ||||||

| Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable † | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Meeting physical activity recommendations during the Ciclovía † | ||||

| Covariates | Sex | 0.90 | [0.54; 1.49] | 0.684 |

| Socio-economic status | ||||

| Low | Reference group | |||

| Middle | 0.94 | [0.27; 3.23] | 0.928 | |

| High | 1.21 | [0.66; 2.18] | 0.540 | |

| Highest level of educational attainment | ||||

| Primary | Reference group | |||

| Secondary/High school | 0.92 | [0.32; 2.57] | 0.875 | |

| College/technical | 1.43 | [0.51; 3.94] | 0.490 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 1.88 | [0.63; 5.59] | 0.258 | |

| Bogotá | Mexico City | Santiago de Cali | Santiago de Chile | Overall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | % | p-Value | % | p-Value | % | p-Value | % | p-Value | p-Value |

| Average percentage of the participants’ trajectories in | |||||||||

| Low SES | 15.13 | <0.001 | 0.24 | <0.001 | 16.20 | <0.001 | 10.23 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Middle SES | 66.24 | 13.88 | 68.55 | 77.46 | <0.001 | ||||

| High SES | 18.63 | 85.89 | 15.26 | 12.31 | <0.001 | ||||

| Maximum difference (percentile) by SES-of-origin † | |||||||||

| Low SES | 33.58 | <0.001 | 13.84 | <0.001 | 30.38 | <0.001 | 15.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Middle SES | 8.94 | 1.55 | 16.22 | −0.91 | <0.001 | ||||

| High SES | −25.60 | −11.06 | −17.25 | −2.76 | <0.001 | ||||

| Average distance traveled (km) by SES origin | |||||||||

| Low SES | 14.75 | 0.004 | 14.00 | 0.060 | 6.25 | 0.377 | 7.75 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Middle SES | 10.75 | 10.50 | 5.25 | 6.25 | <0.001 | ||||

| High SES | 9.25 | 14.00 | 4.75 | 3.75 | <0.001 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mejia-Arbelaez, C.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Mora Vega, R.; Flores Castillo, M.; Truffello, R.; Martínez, L.; Medina, C.; Guaje, O.; Pinzón Ortiz, J.D.; Useche, A.F.; et al. Social Inclusion and Physical Activity in Ciclovía Recreativa Programs in Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020655

Mejia-Arbelaez C, Sarmiento OL, Mora Vega R, Flores Castillo M, Truffello R, Martínez L, Medina C, Guaje O, Pinzón Ortiz JD, Useche AF, et al. Social Inclusion and Physical Activity in Ciclovía Recreativa Programs in Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020655

Chicago/Turabian StyleMejia-Arbelaez, Carlos, Olga L. Sarmiento, Rodrigo Mora Vega, Mónica Flores Castillo, Ricardo Truffello, Lina Martínez, Catalina Medina, Oscar Guaje, José David Pinzón Ortiz, Andres F Useche, and et al. 2021. "Social Inclusion and Physical Activity in Ciclovía Recreativa Programs in Latin America" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020655

APA StyleMejia-Arbelaez, C., Sarmiento, O. L., Mora Vega, R., Flores Castillo, M., Truffello, R., Martínez, L., Medina, C., Guaje, O., Pinzón Ortiz, J. D., Useche, A. F., Rojas-Rueda, D., & Delclòs-Alió, X. (2021). Social Inclusion and Physical Activity in Ciclovía Recreativa Programs in Latin America. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020655