Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How can EU countries be classified in relation to the degree of employee telework adoption during the emergency measures adopted by governmental authorities in 2020?

- Which are the fundamental features that can be highlighted for the countries included in each class and what kind of recommendations can be made in terms of increasing the adaptability to these new work arrangements?

- Which are the main scenarios to be implemented by the decision makers from Romania in order to ensure the smooth transition of the country from a class with a moderate level of remote work implementation into a class with a higher ranking pertaining to telework adoption?

- ✓

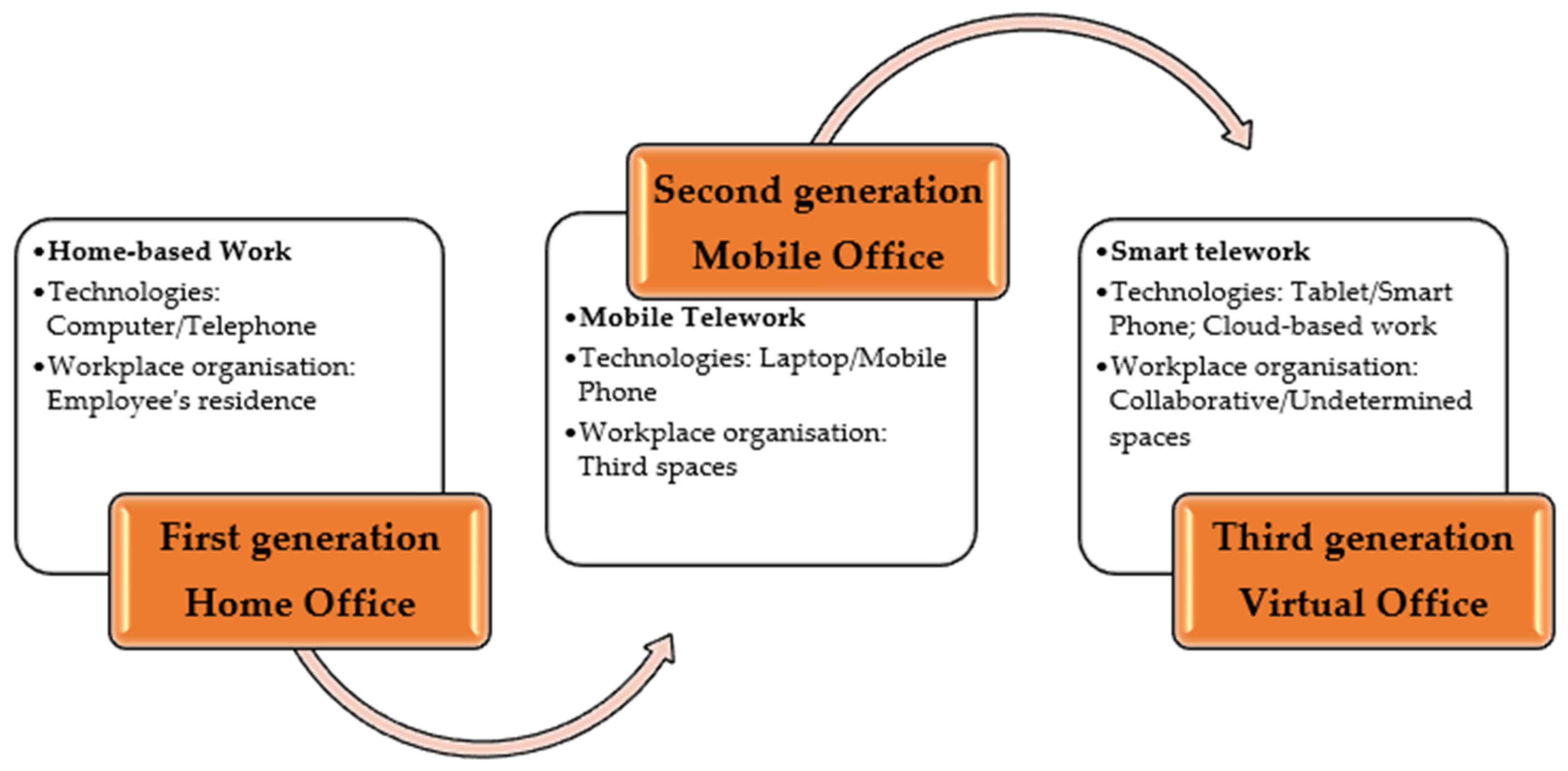

- In paragraph 2.1, we took stock of the core concepts and debates from the literature regarding the astonishing evolution of telework alongside three overlapping generations: home office; mobile office; and virtual office;

- ✓

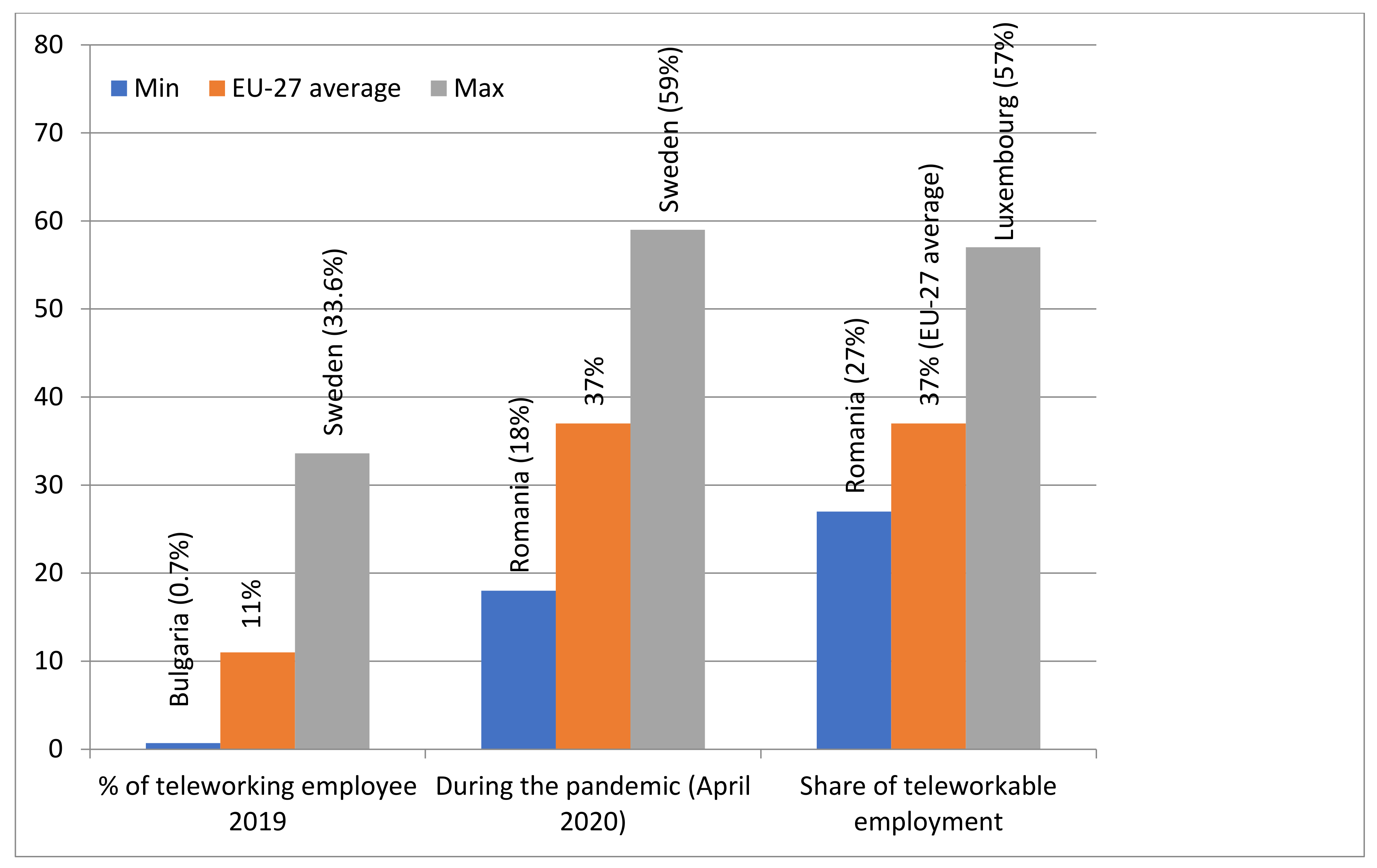

- Paragraph 2.2 was devoted to a short presentation of the state of the art regarding the telework patterns implemented before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period; the main implications on the level of adoption propensity manifested both by employers and employees from the European Union were also discussed.

2. Conceptual Framework of Telework and Literature Review

2.1. The Conceptual Framework

2.2. Teleworking in the EU in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic—A Short Literature Review

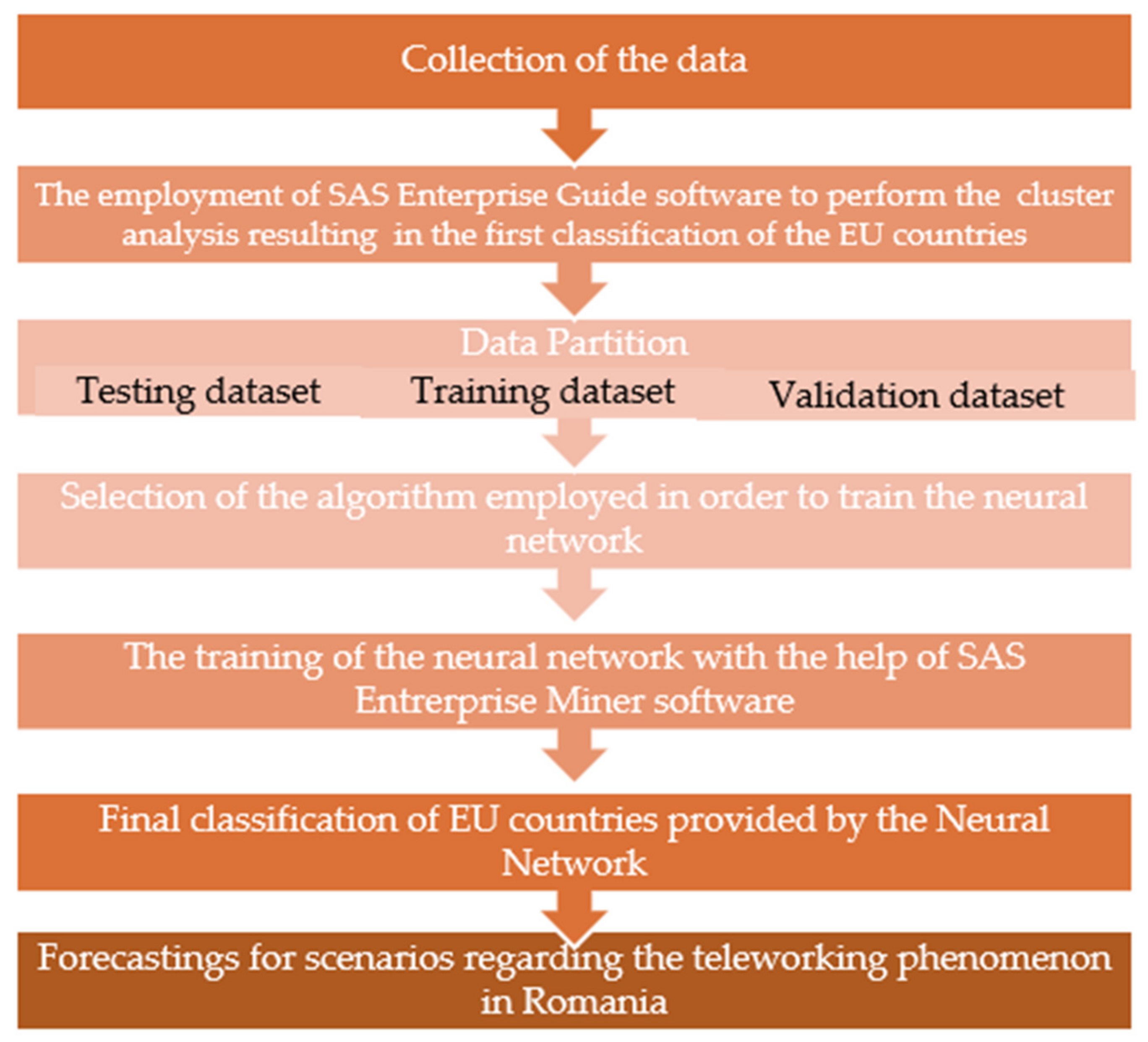

3. Research Methodology

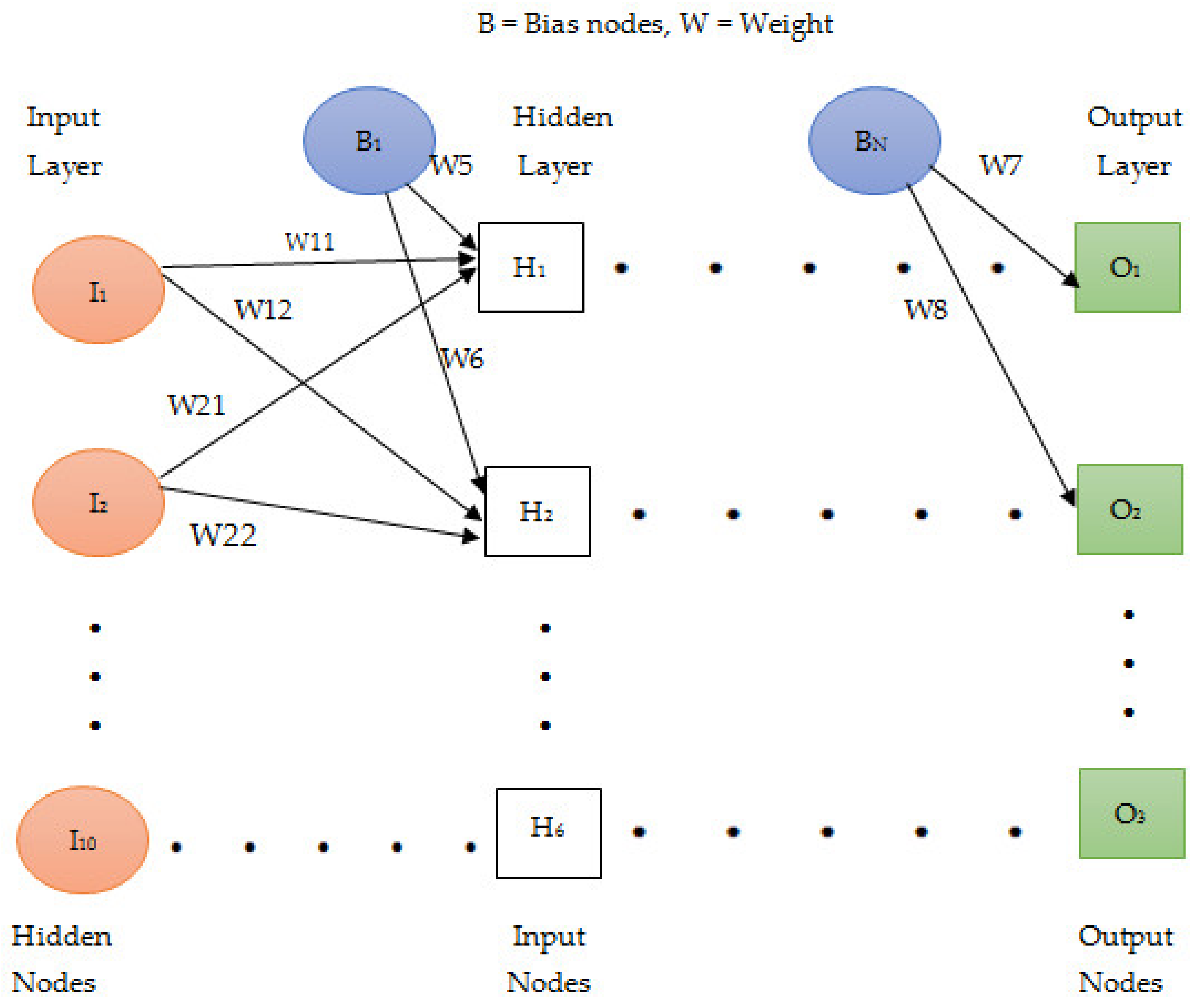

3.1. The Neural Network Models—Theoretical Grounds

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Data and Measures

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. The Cluster Analysis

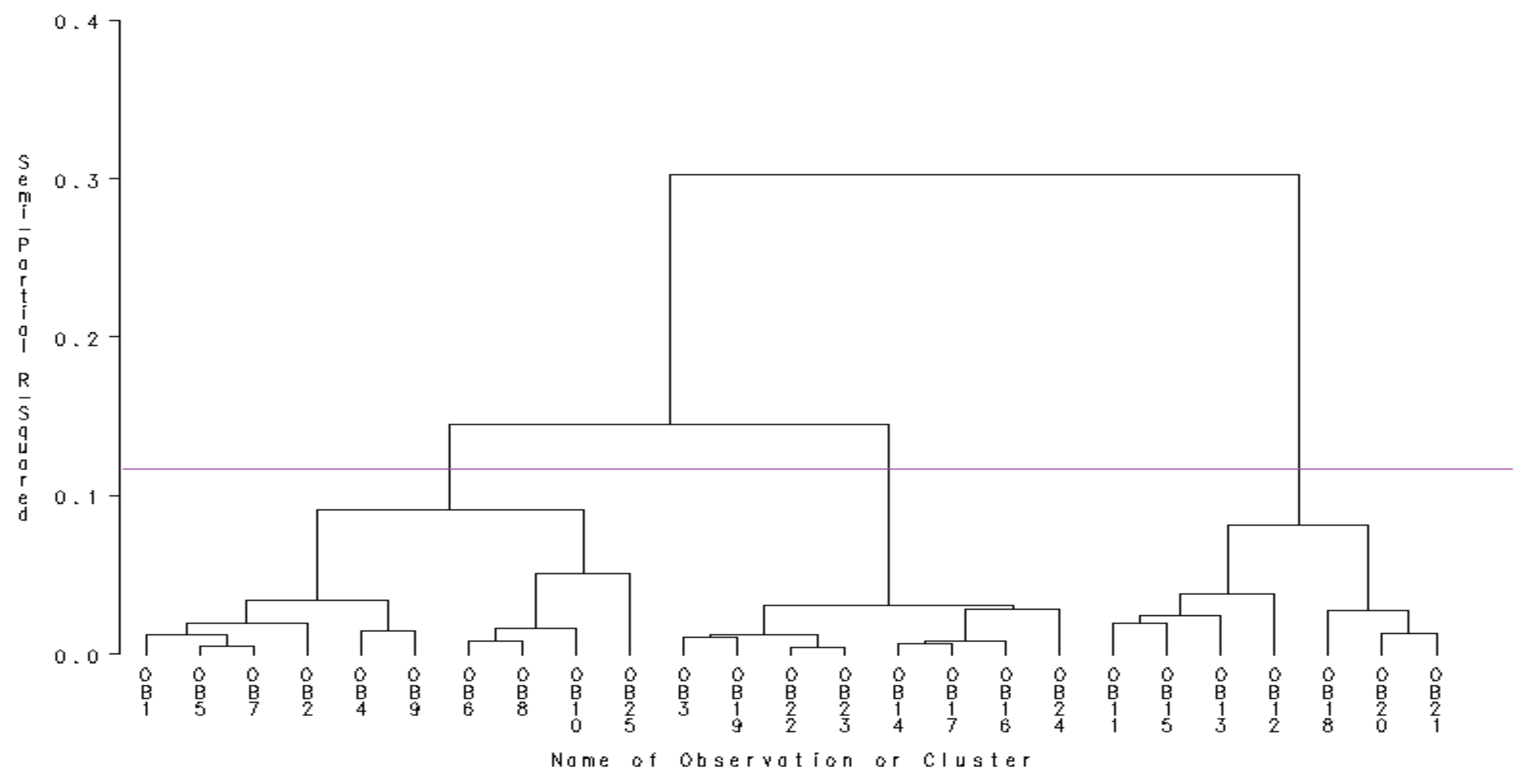

- If the graph is cut below 0.1, then five classes of countries could be individualized, but the distance between them would be a very small one. Although this situation is the most accurate from the statistical point of view, it does not fit reality because the existing dissimilarities between countries in terms of telework adoption might be easily overlooked;

- If the cut is between 0.2 and 0.3, then two large and well-defined classes could be distinguished, but the differences between the objects that compose the same class would be significant. Such an approach would affect the object heterogeneity and would be inconsistent with the very theoretical foundations of cluster analysis;

- If the cut is in the range [0.1, 0.2] and is closer to 0.1, then we should obtain three distinct classes that meet the requirements of the cluster analysis both from the statistical point of view and from the real perspective of the issue being addressed.

- Class 1: Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, Italy, Austria;

- Class 2: Slovakia, France, Bulgaria, Romania, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia;

- Class 3: Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Spain, Lithuania, Poland, Latvia.

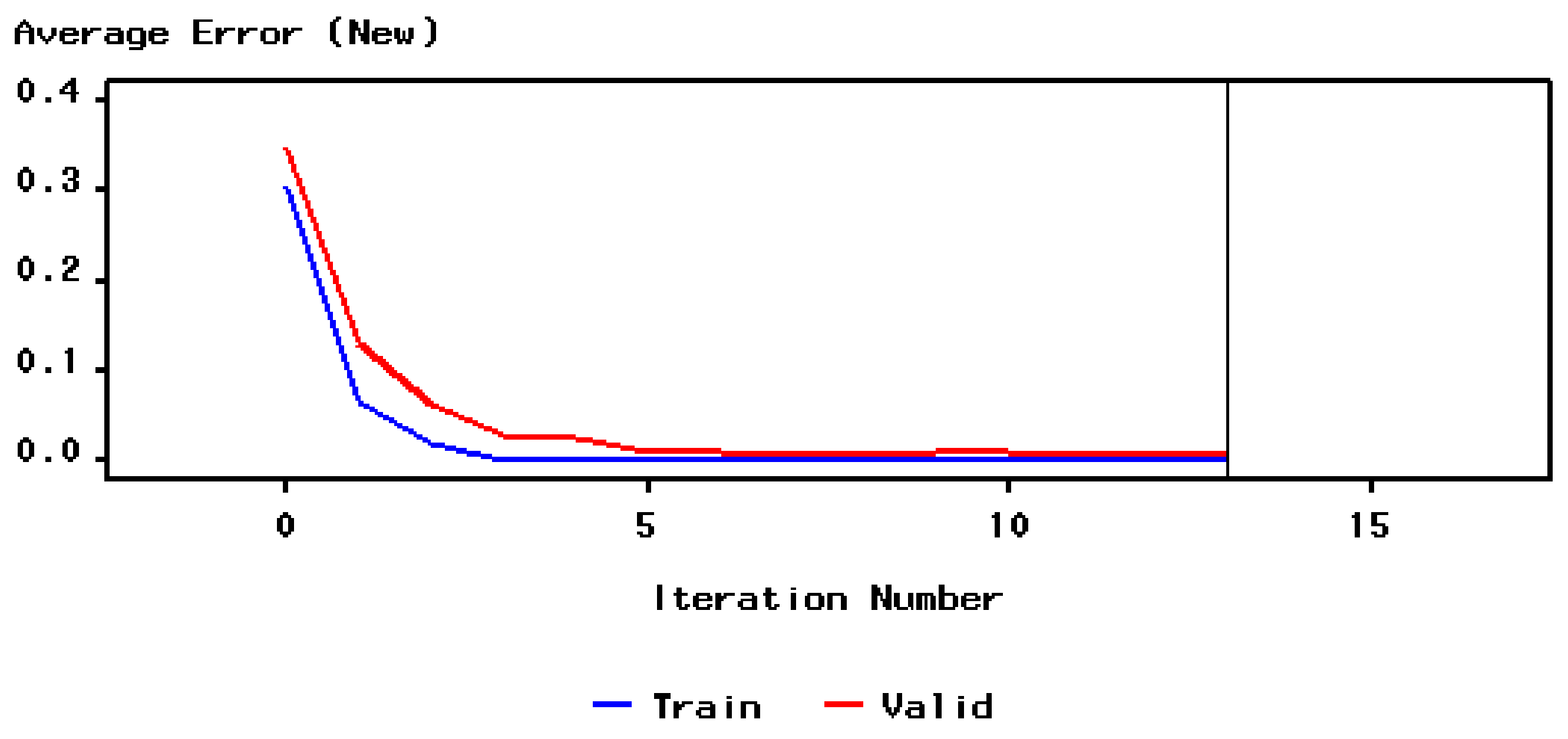

4.3. The Training of the Neural Network

- ✓

- The values of variables I1–I10 fall into the input dataset category;

- ✓

- the output variables Class 1, Class 2, Class 3 were considered categorical variables with two possible values: 1 (if a specific country belongs to that class) and 0 (if the country does not belong to that class).

- The NN training dataset, covered by data gathered for Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Greece, Croatia, Portugal, France, Spain, Romania, Lithuania, Czech Republic, Poland, Latvia, and Austria;

- The NN validation dataset, represented by data collected for Sweden, Ireland, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Slovakia;

- The NN testing dataset, encompassing data put together for Slovakia, Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Estonia.

- For the intermediate layer, the functions are presented in Equations (5)–(10):

H1 = −0.29 × I1 − 1.13 × I2 − 0.43 × I3 − 1.07 × I4 + 1.1 × I5 − 1.52 × I6 + 0.24 × I7 − 0.32 × I8 − 0.09 × I9 − 1.75 × I10;

H1 = −0.26 + H1;(5) H2 = −0.56 × I1 − 0.57 × I2 + 0.08 × I3 − 0.24 × I4 + 2.12 × I5 + 0.94 × I6 + 0.55 × I7 + I8 − 0.36 × I9 − 0.41 × I10;

H2 = 0.54 + H2;(6) H3 = 0.46 × I1 + 0.19 × I2 + 0.13 × I3 + 0.83 × I4 + 0.65 × I5 + 0.24 × I6 − 0.67 × I7 + 0.05 × I8 − 0.54 × I9 + 0.56 × I10;

H3 = 1.13 + H3;(7) H4 = 0.63 × I1 − 0.56 × I2 + 0.29 × I3 − 0.34 × I4 − 0.95 × I5 − 1.93 × I6 − 0.73 × I7 − 0.67 × I8 + 0.37 × I9 − 1.7 × I10;

H4 = 1.88 + H4;(8) H5 = − 0.39 × I1 − 0.37 × I2 + 0.38 × I3 − 0.032 × I4 − 0.4 × I5 − 0.18 × I6 + 0.67 × I7 + 0.003 × I8 − 0.38 × I9 − 0.03 × I10;

H5 = −1.12 + H5;(9) H6 = −0.58 × I1 − 0.55 × I2 − 0.89 × I3 − 0.39 × I4 + 0.24 × I5 − 1.01 × I6 + 0.031 × I7 − 0.39 × I8 + 0.34 × I9 − 0.83 × I10;

H6 = −0.02 + H6;(10) - for the output layer, the functions are described with the help of Equations (11)–(13):

Class1 = −4.72 × H1 − 7.45 × H2 − 2.02 × H3 + 2.41 × H4 + 0.33 × H5 + 0.073 × H6;

Class1 = −2.12 + Class1;(11) Class2 = −1.3 × H1 + 5.51 × H2 + 3 × H3 − 10.78 × H4 + 1.145 × H5 − 3.38 × H6;

Class2 = −1.03 + Class2;(12) Class3 = 5.71 × H1 + 2.26 × H2 − 1.23 × H3 + 2.75 × H4 + 0.73 × H5 + 1.93 × H6;

Class3 = −1.63 + Class3.(13)

- Class 1: Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, Estonia, Austria;

- Class 2: Slovakia, France, Bulgaria, Romania, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia;

- Class 3: Greece, Croatia, Portugal, Spain, Lithuania, Poland, Latvia, Italy.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Overview on the Degree of Telework Embracement by Groups of EU Countries

5.2. Drawing Up a Few Scenarios in Order to Increase the Degree of Telework Adoption in Romania

- I3 > 75%, meaning that teleworkers should be able to procure their own suitable equipment that will allow them to conduct their work in optimal conditions. Although the Telework Law that came into force in Romania in 2018 stipulated the employers’ responsibility to provide remote employees with the necessary work equipment, the legal provisions were not fully observed due to the emergency circumstances. However, through Governmental Emergency Ordinance no. 132/2020, employers were granted a one-off payment of 2500 lei (around EUR 514) for each employee who worked from home for at least 15 days. In order to support the post-pandemic increase in the uptake of telework according to Scenarios 1 and 2, governmental authorities have to continue the development of funding programmes to facilitate access for low-income employees to proper infrastructures and tools that are adequate for teleworking;

- I5 < 45%, meaning a substantial decrease in the amount of physical contact with other people while performing work tasks. To this end, modern communication channels must be enhanced in order to establish efficient connections between employees: emails, phone calls, text messages, video conferences, social media sites, other dedicated platforms, etc.;

- I9 > 45%, i.e., the level of maintaining the same work schedule also has to be increased in order to establish clear boundaries between professional life and family responsibilities in the framework of teleworking. Thus, research has revealed that preserving the number of working hours while gaining additional flexibility in organizing the working schedule is synonymous with raising the degree of employee job satisfaction [54,69].

- I10 > 80%, which is to say that the degree of the non-involvement of family problems and responsibilities in the process of conducting work tasks represents an issue that requires greater importance. Thus, recent studies from the literature have suggested that the burnout generated by constant connection to work tasks, supplementary demands, unreasonable deadlines, and the lack of group-problem solving in the workplace are prone to impair teleworker satisfaction. On the other hand, a positive relationship was established between high levels of professional competences, work–life balance, organizational culture degree of openness towards remote work, and overall well-being [70,71]. Moreover, safety issues in the framework of telework must be addressed both at the company and at the national level to serve the need for new legislative measures regarding employee protection against the psychosocial risks that can occur due to rapid digitalization;

- I6 > 45%, which reflects the focus on maintaining or increasing work performance—a complex variable—which can simultaneously be affected by a few relevant determinants such as individual characteristics (i.e., self-management procedures), home environment factors (i.e., the existence of suitable telework pre-requisites), and job peculiarities (i.e., balanced workload) [66].

- I8 > 75%, meaning that in the post pandemic era, public authorities and companies have to stress the importance of raising the employee level of awareness regarding telework adoption [72]. Moreover, at the company level, multinationals from the EU countries have instituted company-characteristic teleworking procedures, often pushed forward by the precipitated exposure to remote working during the emerging state. Thus, recent qualitative research involving main Romanian stakeholders [65] revealed that the measures implemented in the emergency state both at the public and private levels were defficient and rather unsyncronized. Within this framework, the need for further investment in digital infrastructures, re-skilling programmes, and training courses on well-being has been intensely exposed;

- I9 > 45% and I10 > 75%, that is to say additional far-reaching reforms need to be made in terms of telework legislation (especially for the public domain), with direct implications for the arrangements regarding the improvement of work–life balance. For instance, Romania should follow the example of other Member States (such as France, Germany, Spain) that adopted specific legislation in order to restrict out-of-working hours electronic communications and to defend the right to disconnect (that protects the employee against the psychosocial stress caused by any unreasonable requirements regarding his/her permanent availability on line). On another train of thought, at the European level, two recent directives—The Work–Life Balance Directive and the Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions Directive—are due to be fully applied by the EU countries by 2022 and address, inter alia, the protection of flexible work schedules for employees with children up to 8 years of age while implementing well established working time patterns [62].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Essential | Teleworkable | Partly Active | Mostly Non-Essent | Closed | All Sectors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | 6.45 | 15.26 | 6.03 | 5.75 | 9.51 | 8.58 |

| FR | 12.35 | 19.86 | 11.13 | 9.10 | 14.71 | 13.94 |

| IT | 2.87 | 8.56 | 3.85 | 2.05 | 4.05 | 4.31 |

| ES | 4.02 | 12.11 | 4.14 | 4.08 | 4.04 | 6.01 |

| PL | 11.64 | 15.14 | 5.94 | 4.06 | 9.11 | 9.44 |

| NL | 20.28 | 41.70 | 15.59 | 19.51 | 21.98 | 25.41 |

| RO | 0.47 | 1.02 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.57 |

| CZ | 3.68 | 12.96 | 6.08 | 3.29 | 14.89 | 6.96 |

| SE | 12.11 | 30.59 | 18.71 | 16.26 | 19.27 | 20.56 |

| BE | 10.35 | 24.25 | 10.47 | 10.91 | 17.49 | 14.88 |

| HU | 2.61 | 7.94 | 4.12 | 2.31 | 5.07 | 4.30 |

| AT | 18.04 | 25.97 | 10.58 | 8.08 | 16.23 | 16.21 |

| GR | 1.70 | 9.05 | 1.29 | 2.48 | 1.61 | 3.59 |

| PT | 2.65 | 17.03 | 1.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.14 |

| BG | 0.34 | 1.34 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.97 | 0.59 |

| FI | 16.32 | 37.23 | 17.55 | 16.03 | 23.20 | 22.25 |

| SK | 5.20 | 10.96 | 7.13 | 3.74 | 5.70 | 6.42 |

| DK | 8.13 | 23.38 | 6.92 | 4.03 | 0.61 | 10.53 |

| IE | 7.89 | 13.69 | 0.75 | 2.63 | 0.00 | 6.55 |

| HR | 3.18 | 7.80 | 2.88 | 7.76 | 3.31 | 4.16 |

| LT | 5.24 | 3.64 | 3.48 | 2.07 | 3.72 | 3.70 |

| SI | 9.05 | 24.71 | 10.09 | 5.99 | 12.34 | 12.43 |

| LV | 5.67 | 5.16 | 2.30 | 1.18 | 4.71 | 3.91 |

| EE | 9.50 | 23.23 | 12.41 | 8.95 | 14.87 | 13.86 |

| CY | 1.41 | 2.82 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 2.83 | 1.78 |

| LU | 16.32 | 23.62 | 18.41 | 21.06 | 18.65 | 20.74 |

| MT | 3.45 | 13.42 | 4.71 | 5.27 | 9.59 | 7.85 |

| UK | 11.58 | 20.94 | 10.03 | 13.05 | 12.35 | 14.52 |

| EU28 | 8.36 | 17.49 | 7.40 | 6.40 | 9.78 | 10.23 |

References

- Obrad, C. Constraints and Consequences of Online Teaching. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purificación, L.I.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, 2020b, Living, working and COVID-19: Round 2 July 2020 Dublin. Document number: TD/TNC 140.206. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/covid-19 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office. Challenges and opportunities of teleworking for workers and employers in the ICTS financial and services sector: Issues Paper for the Global Dialogue Forum on the Challenges and Opportunities of Teleworking for Workers and Employers in the ICTS and Financial Services Sectors. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/publications/WCMS_531111/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Moraru, R.I.; Băbuț, G.B.; Cioca, L.I. Knowledge management applications in occupational risk assessment processes. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference—The Knowledge-Based Organization: Management and Military Sciences, Sibiu, Romania, 24–26 November 2011; pp. 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- Moraru, R.I.; Băbuț, G.B.; Cioca, L.I. Knowledge-Based Hazard Analysis Guidelines for Operational Transportation Projects. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference—The Knowledge-Based Organization: Management, Sibiu, Romania, 26–28 November 2009; Volume 2, pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini Ceinar, I.; Pacchi, C.; Mariotti, I. Emerging work patterns and different territorial contexts: Trends for the coworking sector in pandemic recovery. Professionalità Studi 2020, 4/III, 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, J.C. Telework in the 21st Century: An Evolutionary Perspective; Edward Elgaronline: Cheltenhamm, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Makimoto, T.; Manners, D. Digital Nomad; John Willey and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization Teleworking during the COVID-19 Pandemic and beyond. 2020. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3878775 (accessed on 18 July 2021).

- Fana, M.; Tolan, S.; Torrejón, S.; Urzi Brancati, C.; Fernández-Macías, E. The COVID Confinement Measures and EU Labor Markets; EUR 30190 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC120578 (accessed on 17 May 2021). [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.; Bisello, M.; González-Vázquez, I.; Fernández-Macías, E. Who Can Telework Today? The Teleworkability of Occupations in the EU; JRC121426; European Union, EU Science Hub: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/policy_brief_-_who_can_telework_today_-_the_teleworkability_of_occupations_in_the_eu_final.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Rueda, E.; Alvaro, R.; Ruta, M.; Rocha, N.; Winkler, D.; Mattoo, A. Pandemic Trade: Covid-19, Remote Work and Global Value Chains; Policy Research Working Paper Series 9508; The World Bank; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/843301610630752625/Pandemic-Trade-Covid-19-Remote-Work-and-Global-Value-Chains.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Stanton, C.; Tiwari, P. Housing Consumption and the Cost of Remote Work; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasada, K.D.V.; Vaidyab, R.W.; Mangipudic, M.R. Effect of occupational stress and remote working on psychological well-being of employees: An empirical analysis during covid-19 pandemic concerning information technology industry in hyderabad. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Peláez, A.; Erro-Garcés, A.; Pinilla García, F.J.; Kiriakou, D. Working in the 21st Century. The Coronavirus Crisis: A Driver of Digitalisation, Teleworking, and Innovation, with Unintended Social Consequences. Information 2021, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, L.; Ferrell, L.; Pettys, G.; Roloff, A. Adapting to Remote Library Services during COVID-19. Med Ref. Serv. Q. 2021, 40, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, A. When Work Goes Remote. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3777324 (accessed on 7 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Soroui, S.T. Understanding the drivers and implications of remote work from the local perspective: An exploratory study into the disreembedding dynamics. Technol. Soc. 2020, 64, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeley, T. Remote Work Revolution: Succeeding from Anywhere; Harper Business: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dura, C.C.; Driga, I.; Isac, C. Environmental reporting by oil and gas multinationals from Russia and Romania: A comparative analysis. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busu, M.; Gyorgy, A. The Mediating Role of the Ability to Adapt to Teleworking to Increase the Organizational Performance. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23. Available online: www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro (accessed on 1 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Mocanu, N.A. Teleworking perspectives for Romanian SMEs after the COVID-19 pandemic. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 8, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymaniak, J.; Lis, K.; Davidavičienė, V.; Pérez-Pérez, M.; Martínez-Sánchez, A. From Stationary to Remote: Employee Risks at Pandemic Migration of Workplaces. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (covid-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Godil, D.I.; Bibi, M.; Yu, Z.; Rizvi, S.M.A. The Economic and Social Impact of Teleworking in Romania: Present Practices and Post Pandemic Developments. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țălnar-Naghi, D.I. Research Note: Job Satisfaction and Working from Home in Romania Before and During COVID-19. Calitatea Vieții 2021, 32, 1–22. Available online: https://www.revistacalitateavietii.ro/journal/article/view/281/229 (accessed on 1 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Petcu, M.A.; Sobolevschi-David, M.I.; Anica-Popa, A.; Curea, S.C.; Motofei, C.; Popescu, A.-M. Multidimensional Assessment of Job Satisfaction in Telework Conditions. Case Study: Romania in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöhrmann, A.M.; Ebner, C. Understanding the bright side and the dark side of telework: An empirical analysis of working conditions and psychosomatic health complaints. New Technol. Work Employment 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Negulescu, O.; Doval, E. Ergonomics and time management in remote working from home. Acta Technol. Napoc. Ser. App. Mat. Mech. Eng. 2021, 64, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Larrea-Araujo, C.; Ayala-Granja, J.; Vinueza-Cabezas, A.; Acosta-Vargas, P. Ergonomic Risk Factors of Teleworking in Ecuador during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratz, N.; Reibenspiess, V.; Eckhardt, A. The Secret to Remote Work—Results of a Case Study with Dyadic Interviews. Sch. Space 2021, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaudon-Tomas, C.M.; Pinto-López, I.N.; Yañez-Moneda, A.L.; Amsler, A. The Effects of Remote Work on Family Relationships. IGI Global 2021, 30–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellido, A. Neural networks in business: A survey of applications (1992–1998). Expert Syst. Appl. 1999, 17, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dase, R.K.; Pawar, D.D. Application of Artificial Neural Network for stock market predictions: A review of literature. Int. J. Mach. Intell. 2010, 2, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Araque, O.; Corcuera-Platas, I.; Sánchez-Rada, J.F.; Iglesias, C.A. Enhancing deep learning sentiment analysis with ensemble techniques in social applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 77, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.I.; Jantan, A.; Omolara, A.E.; Dada, K.V.; Mohamed, N.A.; Arshad, H. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.H.; Juan, Y.-K. Artificial Neural Network Based Decision Model for Alternative Workplaces. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2014, 13, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iordache, A.M.M.; Spircu, L. Using Neural Networks in Rating. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2011, 3, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kulluk, S.; Ozbakir, L.; Baykasoglu, A. Training neural networks with harmony search algorithms for classification problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 25, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, A.M.; Ouahada, K.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. Real Time Security Assessment of the Power System Using a Hybrid Support Vector Machine and Multilayer Perceptron Neural Network Algorithms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trebuňa, P.; Halčinová, J. Experimental Modelling of the Cluster Analysis Processes. Procedia Eng. 2012, 48, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matignon, R. Neural Network Modeling Using SAS Enterprise Miner; Author House: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2009; pp. 51–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, M.; Nachtsheim, C.; Neter, J.; Li, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 555–640. [Google Scholar]

- Mangiameli, P.; Chen, S.K.; West, D. A comparison of SOM neural network and hierarchical clustering methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 93, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedla, A.; Kakhki, F.D.; Jannesari, A. Predictive Modeling for Occupational Safety Outcomes and Days Away from Work Analysis in Mining Operations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engineering Statistics Handbook. Available online: https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda35b.htm (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Gonzalez, S. Neural Networks for Macroeconomic Forecasting: A Complementary Approach to Linear Regression Models; Working Paper; Department of Finance: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000; Volume 7.

- Bérastégui, P. Teleworking in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic: Enabling conditions for a successful transition, European Economic, Employment and Social Policy. Covid-19 Impact Series, 2021, 05. Available online: https://www.etui.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/Teleworking%20in%20the%20aftermath%20of%20the%20Covid-19%20pandemic.%20Enabling%20conditions%20for%20a%20successful%20transition.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Tokarchuk, O.; Gabriele, R.; Neglia, G. Teleworking during the Covid-19 Crisis in Italy: Evidence and Tentative Interpretations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balacescu, A.; Patrascu, A.; Paunescu, L.M. Adaptability to Teleworking in European Countries. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 3, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrad, C.; Circa, C. Determinants of Work Engagement Among Teachers in the Context of Teleworking. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 718. Available online: www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro (accessed on 5 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.-M.; Țuclea, C.-E.; Vrânceanu, D.-M.; Țigu, G. Sustainable Social and Individual Implications of Telework: A New Insight into the Romanian Labor Market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mihailović, A.; Smolović, J.C.; Radević, I.; Rašović, N.; Martinović, N. COVID-19 and Beyond: Employee Perceptions of the Efficiency of Teleworking and Its Cybersecurity Implications. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E.; Vilhelmson, B.; Johansson, M. New Telework, Time Pressure, and Time Use Control in Everyday Life. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. The Digital Economy and Society Index. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Loia, F.; Adinolfi, P. Teleworking as an Eco-Innovation for Sustainable Development: Assessing Collective Perceptions during COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y. Teleworking: Benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technol. Work Employment 2000, 15, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrad, C.; Gherheș, V. A Human Resources Perspective on Responsible Corporate Behavior. Case Study: The Multinational Companies in Western Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davidescu, A.; Apostu, S.-A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees—Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodovici, M.S. The Impact of Teleworking and Digital Work on Workers and Society, European Parliament. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904_EN.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Morilla-Luchena, A.; Muñoz-Moreno, R.; Chaves-Montero, A.; Vázquez-Aguado, O. Telework and Social Services in Spain during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Rapuano, V.; Varkulevičiūtė, K.; Stachová, K. Working from Home—Who is Happy? A Survey of Lithuania’s Employees during the Covid-19 Quarantine Period. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilescu, C. The impact of teleworking and digital work on workers and society. Anex VII-Case study on Romania, European Parliament. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662904/IPOL_STU(2021)662904(ANN05)_EN.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Mihalca, L.; Irimiaș, T.; Brendea, G. Teleworking During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Determining Factors of Perceived Work Productivity, Job Performance, and Satisfaction. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuga, I.; Danciu, A.; Drigă, I. The Profile of the Foreign Investor in the Romanian Chemical Industry. Processes 2020, 8, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Georgescu, G.C.; Gherghina, R.; Duca, I.; Postole, M.A.; Constantinescu, C.M. Determinants of Employees’ Option for Preserving Teleworking after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maican, S.; Muntean, A.; Paștiu, C.; Stępień, S.; Polcyn, J.; Dobra, I.; Dârja, M.; Moisă, C. Motivational Factors, Job Satisfaction, and Economic Performance in Romanian Small Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, D.; Petcu, M.A.; Iulia, D.-S.M.; Cojocariu, R.C. A Muldimensional Approach of the Relationship between Teleworking and Employees Well-Being—Romania during the Pandemic Generated by the Sars-Cov-2 Virus. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 586–600. Available online: www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro (accessed on 25 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Isac, C. Management of succession in family business. Qual. Access Success 2019, 20 (Suppl. 1), 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Dura, C.; Drigă, I. The Impact of Multinational Companies from Romania on Increasing the Level of Corporate Social Responsibility Awareness. Contemp. Econ. 2017, 11, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurofound, 2020, Living, working and COVID-19: First Findings—April 2020, Dublin. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/covid-19 (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Eurofound, 2020, Living, working and COVID-19: Round 3—March 2021, Dublin. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/data/covid-19 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

| Crt. No | Symbol | Variable Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I1 | Satisfaction on the amount of work submitted |

| 2 | I2 | Satisfaction on the quality of work submitted |

| 3 | I3 | Work in optimal conditions with the equipment from home |

| 4 | I4 | Satisfaction with the experience of working from home |

| 5 | I5 | Physical contact with other people during working |

| 6 | I6 | Maintaining constant work performance |

| 7 | I7 | The risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the workplace |

| 8 | I8 | Not accepting work from home before the pandemic |

| 9 | I9 | Keeping the same work schedule during the pandemic |

| 10 | I10 | Non-involvement of family issued and duties in performing work tasks |

| I1 (%) | I2 (%) | I3 (%) | I4 (%) | I5 (%) | I6 (%) | I7 (%) | I8 (%) | I9 (%) | I10 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | 55 | 74.9 | 67.1 | 66.9 | 48.8 | 32.4 | 26.8 | 54.5 | 56.8 | 80.7 |

| Sweden | 53.5 | 63.2 | 65.2 | 60 | 42 | 33.7 | 43.2 | 65.6 | 48.3 | 77.8 |

| Slovakia | 53.7 | 68.7 | 67.3 | 61.1 | 75.3 | 37.2 | 32.5 | 70.4 | 43.3 | 71.6 |

| Finland | 64.6 | 71.2 | 78.6 | 70.8 | 52.9 | 43.1 | 29.4 | 52.5 | 44.2 | 70.2 |

| Germany | 53.3 | 69 | 70.4 | 58.9 | 50.6 | 36.2 | 29.8 | 58.2 | 44.5 | 74.1 |

| Ireland | 57 | 69.7 | 59.2 | 59.6 | 46 | 26 | 35.2 | 69.4 | 34.4 | 67.4 |

| Netherlands | 56.3 | 69.8 | 72 | 60.2 | 43 | 36 | 30.8 | 61.7 | 50 | 79.6 |

| Luxembourg | 57.9 | 68 | 69.2 | 67.1 | 47.2 | 27 | 42 | 64.8 | 32.1 | 68.1 |

| Belgium | 57.1 | 69.3 | 71.6 | 62.1 | 44.1 | 37.1 | 36.1 | 54.4 | 39.2 | 63.3 |

| Italy | 54.6 | 60.3 | 65.1 | 55.9 | 56.4 | 21.1 | 31.5 | 73.1 | 29.4 | 68.5 |

| Greece | 47.7 | 56.6 | 53 | 44.5 | 72.1 | 26.2 | 60.2 | 63 | 31.6 | 68.8 |

| Croatia | 46.9 | 56.9 | 60.2 | 48.4 | 71.5 | 36.1 | 63 | 75.2 | 50.4 | 55.1 |

| Portugal | 51.5 | 63 | 67.7 | 56.3 | 67.6 | 28.6 | 71 | 63.7 | 25.1 | 57.4 |

| France | 48.5 | 63.9 | 65.9 | 59.3 | 65 | 36.5 | 46 | 69.1 | 32.9 | 73.1 |

| Spain | 50.6 | 58.8 | 59.1 | 52.8 | 59.9 | 29 | 51.1 | 72.2 | 26.5 | 58.3 |

| Bulgaria | 53.6 | 63.6 | 66.1 | 62.6 | 61.1 | 39.1 | 44.2 | 66.8 | 45.1 | 73.4 |

| Romania | 55.8 | 70.8 | 65.2 | 60.7 | 67.5 | 40 | 49.9 | 70.5 | 37.6 | 67.6 |

| Lithuania | 47.8 | 56.6 | 60.9 | 57.4 | 73.8 | 29.5 | 29.9 | 67.3 | 42.1 | 70.7 |

| Czech Rep. | 61 | 72.2 | 75.8 | 68.2 | 75.6 | 41.5 | 36.9 | 61.2 | 43.2 | 72.3 |

| Poland | 44.6 | 58.7 | 63.5 | 39.1 | 65.7 | 33 | 36.9 | 62.8 | 31 | 58.7 |

| Latvia | 41.3 | 58.9 | 63.5 | 47.7 | 61.7 | 37.7 | 44.4 | 62.8 | 43.5 | 65 |

| Hungary | 58.3 | 72.7 | 65.9 | 64.2 | 67 | 38.1 | 42 | 64.7 | 41.6 | 83 |

| Slovenia | 56.5 | 71.4 | 66.5 | 61.5 | 70.6 | 41.6 | 40.9 | 64 | 43.7 | 74.8 |

| Estonia | 56.8 | 63.9 | 68.1 | 64.9 | 61.3 | 34 | 47.8 | 50.4 | 50.5 | 74.2 |

| Austria | 70.6 | 82.1 | 79 | 72.4 | 56.2 | 34 | 44.6 | 68.2 | 29.8 | 70.6 |

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skeweness | Kurtosis | Bimodality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 54.1800 | 6.2571 | 0.3524 | 1.1521 | 0.2461 |

| I3 | 66.6440 | 5.9790 | 0.1697 | 0.6238 | 0.2547 |

| I2 | 66.1680 | 6.5783 | 0.2700 | −0.2644 | 0.3405 |

| I5 | 60.1160 | 10.8053 | −0.2608 | −1.2174 | 0.4860 |

| I8 | 64.2600 | 6.4634 | −0.5235 | −0.1944 | 0.3956 |

| I10 | 69.7720 | 7.2389 | −0.3391 | −0.2078 | 0.3477 |

| I7 | 41.8440 | 11.1272 | 0.9636 | 0.7904 | 0.4586 |

| I9 | 39.8720 | 8.4407 | −0.0495 | −0.8348 | 0.3885 |

| I6 | 34.1880 | 5.5756 | −0.5454 | −0.2421 | 0.4089 |

| I4 | 59.3040 | 7.9954 | −0.7928 | 0.6568 | 0.4000 |

| Variable | Eigenvalue | Difference | Proportion | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 274.735896 | 172.544182 | 0.4437 | 0.4437 |

| I3 | 102.191714 | 8.478875 | 0.1650 | 0.6088 |

| I2 | 93.712839 | 33.198663 | 0.1513 | 0.7601 |

| I5 | 60.514176 | 25.968228 | 0.0977 | 0.8578 |

| I8 | 34.545948 | 11.356947 | 0.0558 | 0.9136 |

| I10 | 23.189001 | 9.710345 | 0.0375 | 0.9511 |

| I7 | 13.478656 | 5.199626 | 0.0218 | 0.9728 |

| I9 | 8.279031 | 3.336893 | 0.0134 | 0.9862 |

| I6 | 4.942137 | 1.351202 | 0.0080 | 0.9942 |

| I4 | 3.590936 | - | 0.0058 | 1.0000 |

| Country | Probability of Falling in Class 1 | Probability of Not Falling in Class 1 | Probability of Falling in Class 2 | Probability of Not Falling in Class 2 | Probability of Falling in Class 3 | Probability of Not Falling in Class 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slovakia | 0.000066711 | 0.999933288 | 0.999999997 | 2.475929 × 10−9 | 0.000020891 | 0.99997911 |

| Italy | 0.704275705 | 0.295724294 | 2.930769 × 10−9 | 0.999999997 | 0.994797623 | 0.005202376 |

| Bulgaria | 0.000580391 | 0.999419609 | 0.99999998 | 2.001788 × 10−8 | 0.000013891 | 0.999986109 |

| Hungary | 0.010475582 | 0.989524417 | 0.999999984 | 1.535445 × 10−8 | 1.755392 × 10−6 | 0.999998245 |

| Estonia | 0.999955401 | 0.000044598 | 3.885994 × 10−7 | 0.999999611 | 0.000352685 | 0.999647315 |

| No. crt. | The Initial Values of the Input Variables | New Thresholds for the Input Variables |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | I3 = 65.2%, I5 = 67.5%, I9 = 37.6% | I3 > 75%, I5 < 45%, I9 > 45% |

| 2 | I10 = 67.6%, I3 = 65.2%, I6 = 40% | I10 > 80%, I3 > 80%,I6 > 45% |

| 3 | I8 = 70.5%, I9 = 37.6%, I10 = 67.6% | I8 > 75%, I9 > 50%, I10 > 75% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iordache, A.M.M.; Dura, C.C.; Coculescu, C.; Isac, C.; Preda, A. Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010586

Iordache AMM, Dura CC, Coculescu C, Isac C, Preda A. Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010586

Chicago/Turabian StyleIordache, Ana Maria Mihaela, Codruța Cornelia Dura, Cristina Coculescu, Claudia Isac, and Ana Preda. 2021. "Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010586

APA StyleIordache, A. M. M., Dura, C. C., Coculescu, C., Isac, C., & Preda, A. (2021). Using Neural Networks in Order to Analyze Telework Adaptability across the European Union Countries: A Case Study of the Most Relevant Scenarios to Occur in Romania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010586