Determinants of Psychosocial Resilience Resources in Obese Pregnant Women with Threatened Preterm Labor—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Purpose of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

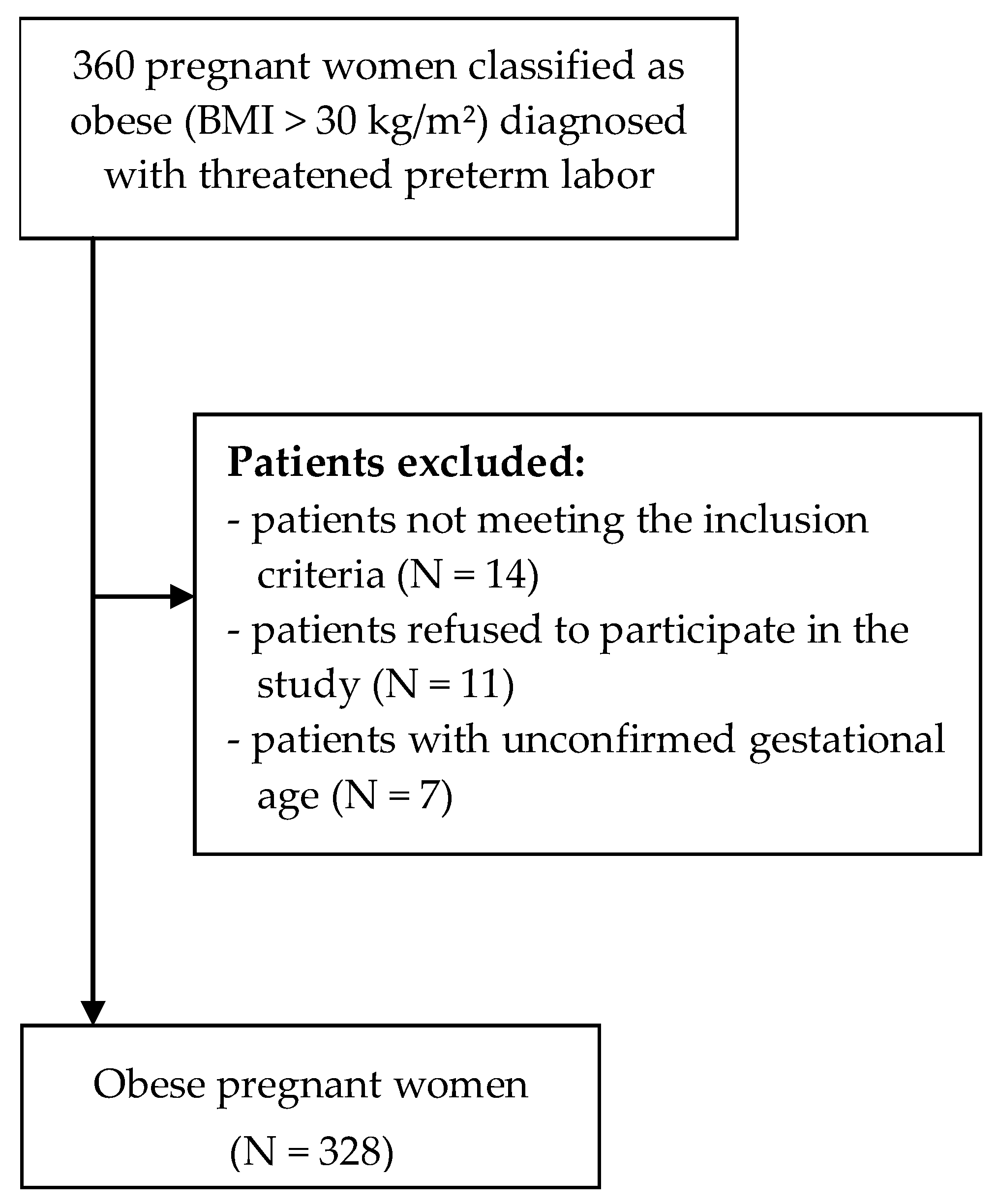

2.1. Study Groups

2.2. Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Chu, Y.; Perin, J.; Zhu, J.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: An updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2016, 388, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delnord, M.; Zeitlin, J. Epidemiology of late preterm and early term births—An international perspective. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cnattingius, S.; Villamor, E.; Johansson, S.; Bonamy, A.-K.E.; Persson, M.; Wikström, A.-K.; Granath, F. Maternal obesity and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA 2013, 309, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in bodymass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2019/EN_WHS_2019_Main.pdf. (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- McDonald, S.; Kingston, D.; Bayrampour, H.; Dolan, S.; Tough, S. Cumulative psychosocial stress, coping resources, and preterm birth. Archiv. Womens Ment. Health 2014, 17, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Tirone, V.; Holmgreen, L.; Gerhart, J. Conservation of resources theory applied to major stress. In Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behaviour; Fink, G., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Niessen, C.; Jimmieson, N. Threat of Resource Loss: The Role of Self-Regulation in Adaptive Task Performance. J. Appl. Psych. 2016, 101, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfeld, P.; Preusser, F.; Margraf, J. Costs and benefits of self-efficacy: Differences of the stress response and clinical implications. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 75, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S.; Chan, S.; Chong, Y.; He, H. Predictors of Maternal Parental Self-Efficacy Among Primiparas in the Early Postnatal Period. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 1604–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, S.; Maxson, P.; Truong, T.; Swamy, G. Psychosocial Stress and Preterm Birth: The Impact of Parity and Race. Matern. Child. Health J. 2018, 22, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangiordano, I.; Sahani, H.; Di Mascio, D.; Saccone, G.; Bellussi, F.; Berghella, A.; Braverman, A.; Berghella, V. Optimism during pregnancy and obstetrical outcomes: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 248, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosińska, P. Poczucie własnej skuteczności i lokalizacja kontroli zdrowia jako predyktory troski o zdrowie w grupie matek małych dzieci. FetR 2017, 4, 113–142. [Google Scholar]

- Suff, N.; Story, L.; Shennan, A.H. The prediction of preterm delivery: What is new? Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019, 24, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. Global Database on Body Mass Index: BMI Classification 2006. Available online: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage¼intro_3.html (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Tucker, J.; McGuire, W. Epidemiology of preterm birth. BMJ 2004, 329, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M.; Juczyński, Z. Skala Uogólnionej Własnej Skuteczności–GSES. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; Juczyński, Z., Ed.; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lonnfjord, V.; Hagquist, C. The psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the general self-efficacy scale: A Rasch analysis based on adolescent data. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Test Orientacji Życiowej–LOT-R. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; Juczyński, Z., Ed.; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wallston, K.A.; Wallston, B.S.; DeVellis, R. Wielowymiarowa Skala Umiejscowienia Kontroli Zdrowia–MHLC. In Narzędzia Pomiaru w Promocji i Psychologii Zdrowia; Juczyński, Z., Ed.; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lawn, J.E.; Blencowe, H.; Waiswa, P.; Amouzou, A.; Mathers, C.; Hogan, D.; Flenady, V.; Frøen, J.F.; Qureshi, Z.U.; Calderwood, C.; et al. Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016, 377, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amark, H.; Westgren, M.; Persson, M. Prediction of stillbirth in women with overweight or obesity—A register–based cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, B.; Xu, G.; Sun, Y.; Du, Y.; Gao, R.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Santillan, M.K.; Bao, W. Association between maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and preterm birth according to maternal age and race or ethnicity: A population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Zhu, Y.; Grantz, K.L.; Hinkle, S.N.; Chen, Z.; Wallace, M.E.; Smarr, M.M.; Epps, N.M.; Mendola, P. Obstetric and Neonatal Risks Among Obese Women Without Chronic Disease. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slack, E.; Best, K.E.; Rankin, J.; Heslehurst, N. Maternal obesity classes, preterm and post-term birth: A retrospective analysis of 479,864 births in England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razurel, C.; Kaiser, B.; Antonietti, J.P.; Epiney, M.; Sellenet, C. Relationship between perceived perinatal stress and depressive symptoms, anxiety, and parental self-efficacy in primiparous mothers and the role of social support. Women Health 2017, 57, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernand, J.J.; Kunseler, F.C.; Oosterman, M.; Beekman, A.T.; Schuengel, C. Prenatal changes in parenting self-efficacy: Linkages with anxiety and depressive symptoms in primiparous women. Inf. Ment. Health J. 2014, 35, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, N.K. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 21, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Zarajczyk, M.; Pięta, B.; Bień, A. Quality of Life, Social Support, Acceptance of Illness, and Self-Efficacy among Pregnant Women with Hyperglycemia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Mróz, M.; Bień, A. Quality of life, social support and self-efficacy in women after a miscarriage. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, R.; Simpson, N.; Dryerm, R. Pregnancy-Related Anxiety, Perceived Parental Self-Efficacy and the Influence of Parity and Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, Y.X.; Razak, N.K.B.A.; Cheng, L.J.; Lau, Y. Determinants of childbirth self-efficacy among multi-ethnic pregnant women in Singapore: A structural equation modelling approach. Midwifery 2020, 87, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomy Mahmoodabad, S.S.; Karimiankakolaki, Z.; Kazemi, A.; Fallahzadeh, H. Self-efficacy and perceived barriers of pregnant women regarding exposure to second-hand smoke at home. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 29, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Parker, E.J.; Roberts-Thomson, K.F.; Lawrence, H.P.; Broughton, J. Self-efficacy and self-rated oral health among pregnant aboriginal Australian women. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, P.; Kim, E.S.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Zevon, E.S.; Trudel-Fitzgerald, C.; Grodstein, F. Optimism and Healthy Aging in Women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.A.; Yang, H.; Kwawukume, Y.; Gupta, A.; Zhu, Y.; Koranteng, I.; Elsayed, Y.; Wei, Y.; Greene, J.; Calhoun, C.; et al. Optimism/pessimism and health-related quality of life during pregnancy across three continents: A matched cohort study in China, Ghana, and the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loh, J.; Harms, C.; Harman, B. Effects of Parental Stress, Optimism, and Health-Promoting Behaviors on the Quality of Life of Primiparous and Multiparous Mothers. Nurs. Res. 2017, 66, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puente, C.; Morales, D.; Monge, F. Religious Coping and Locus of Control in Normal Pregnancy: Moderating Effects Between Pregnancy Worries and Mental Health. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 1598–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, K.; Rayens, M. Ethnicity, smoking status, and preterm birth as predictors of maternal locus of control. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2015, 24, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kordi, M.; Heravan, M.B.; Asgharipour, N.; Akhlaghi, F.; Mazloum, S.R. Does maternal and fetal health locus of control predict self-care behaviors among women with gestational diabetes? J. Edu. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of the Group | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 y/o | 95 | 29.0 |

| 26–35 y/o | 190 | 57.9 | |

| More than 35 y/o | 43 | 13.1 | |

| Residence | Urban | 179 | 54.6 |

| Rural | 149 | 45.4 | |

| Relationship status | Married | 237 | 72.3 |

| Single | 91 | 27.7 | |

| Education | Other than higher | 168 | 51.2 |

| Higher | 160 | 48.8 | |

| Socio-economic standing | Satisfying | 170 | 51.8 |

| Not satisfying | 158 | 48.2 | |

| Number of pregnancies | First pregnancy | 132 | 40.2 |

| Second pregnancy | 146 | 44.5 | |

| Third or subsequent pregnancy | 50 | 15.2 | |

| Number of previous deliveries | None | 251 | 76.5 |

| One | 72 | 22.0 | |

| Two or more | 5 | 1.5 | |

| Week of pregnancy | 23-27 Hbd | 96 | 29.3 |

| 28-32 Hbd | 113 | 34.5 | |

| 32-37 Hbd | 119 | 36.3 | |

| Concurrent chronic disease: hypertension, diabetes, thyroid and heart diseases | No | 149 | 45.4 |

| Yes | 179 | 54.6 | |

| Resilience Resources | M | Me | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSES | 28.02 | 28.00 | 3.67 | 15.00 | 38.00 | |

| LOT R | 16.20 | 17.00 | 3.95 | 4.00 | 24.00 | |

| MHLC | Internal | 26.08 | 27.00 | 3.68 | 15.00 | 36.00 |

| Impact of others | 21.52 | 22.00 | 4.06 | 10.00 | 31.00 | |

| Random events | 19.08 | 19.00 | 5.36 | 6.00 | 32.00 | |

| GSES | LOT-R | MHLC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | Impact of Others | Random Events | ||||

| GSES | - | |||||

| LOT-R | 0.479 ** | - | ||||

| MHLC | Internal | 0.365 ** | 0.129 * | - | ||

| Impact of others | −0.149 ** | 0.062 | 0.099 | - | ||

| Random events | −0.120 * | −0.434 ** | −0.032 | −0.125 * | - | |

| Predictors | GSES F = 3.888; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.074 | LOT-R F = 12.890; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.247 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p | |

| Age | −0.033 | 0.314 | −0.006 | −0.106 | 0.916 | 0.433 | 0.304 | 0.069 | 1.422 | 0.156 |

| Residence A | 0.660 | 0.403 | 0.090 | 1.639 | 0.102 | −0.023 | 0.390 | −0.003 | −0.059 | 0.953 |

| Relationship status B | 0.734 | 0.445 | 0.090 | 1.648 | 0.100 | 3.349 | 0.431 | 0.381 | 7.763 | 0.000 |

| Socio-economic standing C | 1.146 | 0.399 | 0.156 | 2.876 | 0.004 | 1.084 | 0.386 | 0.137 | 2.808 | 0.005 |

| Education D | 0.014 | 0.402 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.971 | 0.130 | 0.389 | 0.016 | 0.333 | 0.739 |

| Number of pregnancies E | 0.720 | 0.454 | 0.096 | 1.586 | 0.114 | −0.514 | 0.440 | −0.064 | −1.169 | 0.243 |

| Number of previous deliveries F | −1.650 | 0.520 | −0.191 | −3.174 | 0.002 | −0.267 | 0.503 | −0.029 | −0.530 | 0.597 |

| Week of pregnancy | −0.364 | 0.250 | −0.080 | −1.460 | 0.145 | −1.129 | 0.242 | −0.231 | −4.669 | 0.000 |

| Occurrence of chronic diseases:G | −1.068 | 0.402 | −0.145 | −2.658 | 0.008 | −1.020 | 0.389 | −0.129 | −2.621 | 0.009 |

| Predictors | MHLC—Impact of Others F = 2.258; p = 0.018; R2 = 0.033 | MHLC—Random Events F = 7.986; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.161 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | t | p | B | SE | β | t | p | |

| Age | −0.028 | 0.355 | −0.004 | −0.079 | 0.937 | −0.433 | 0.436 | −0.051 | −0.992 | 0.322 |

| Residence A | −0.256 | 0.455 | −0.031 | −0.562 | 0.575 | 1.240 | 0.559 | 0.115 | 2.216 | 0.027 |

| Relationship status B | 1.038 | 0.503 | 0.115 | 2.064 | 0.040 | −3.359 | 0.619 | −0.281 | −5.431 | 0.000 |

| Socio-economic standing C | 0.984 | 0.450 | 0.121 | 2.186 | 0.030 | −1.708 | 0.554 | −0.159 | −3.085 | 0.002 |

| Education D | 0.270 | 0.454 | 0.033 | 0.594 | 0.553 | 0.002 | 0.558 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.997 |

| Number of pregnancies E | 0.230 | 0.513 | 0.028 | 0.448 | 0.654 | −0.204 | 0.630 | −0.019 | −0.323 | 0.747 |

| Number of previous deliveries F | 1.189 | 0.587 | 0.124 | 2.024 | 0.044 | −0.995 | 0.722 | −0.079 | −1.378 | 0.169 |

| Week of pregnancy | 0.074 | 0.282 | 0.015 | 0.263 | 0.793 | 1.506 | 0.347 | 0.227 | 4.344 | 0.000 |

| Occurrence of chronic diseases: G | 0.572 | 0.454 | 0.070 | 1.259 | 0.209 | 0.710 | 0.558 | 0.066 | 1.271 | 0.205 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bień, A.; Rzońca, E.; Grzesik-Gąsior, J.; Pieczykolan, A.; Humeniuk, E.; Michalak, M.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Wdowiak, A. Determinants of Psychosocial Resilience Resources in Obese Pregnant Women with Threatened Preterm Labor—A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010590

Bień A, Rzońca E, Grzesik-Gąsior J, Pieczykolan A, Humeniuk E, Michalak M, Iwanowicz-Palus G, Wdowiak A. Determinants of Psychosocial Resilience Resources in Obese Pregnant Women with Threatened Preterm Labor—A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010590

Chicago/Turabian StyleBień, Agnieszka, Ewa Rzońca, Joanna Grzesik-Gąsior, Agnieszka Pieczykolan, Ewa Humeniuk, Małgorzata Michalak, Grażyna Iwanowicz-Palus, and Artur Wdowiak. 2021. "Determinants of Psychosocial Resilience Resources in Obese Pregnant Women with Threatened Preterm Labor—A Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010590

APA StyleBień, A., Rzońca, E., Grzesik-Gąsior, J., Pieczykolan, A., Humeniuk, E., Michalak, M., Iwanowicz-Palus, G., & Wdowiak, A. (2021). Determinants of Psychosocial Resilience Resources in Obese Pregnant Women with Threatened Preterm Labor—A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010590