Development of Psychological First Aid Guidelines for People Who Have Experienced Disasters

Abstract

:1. Introduction

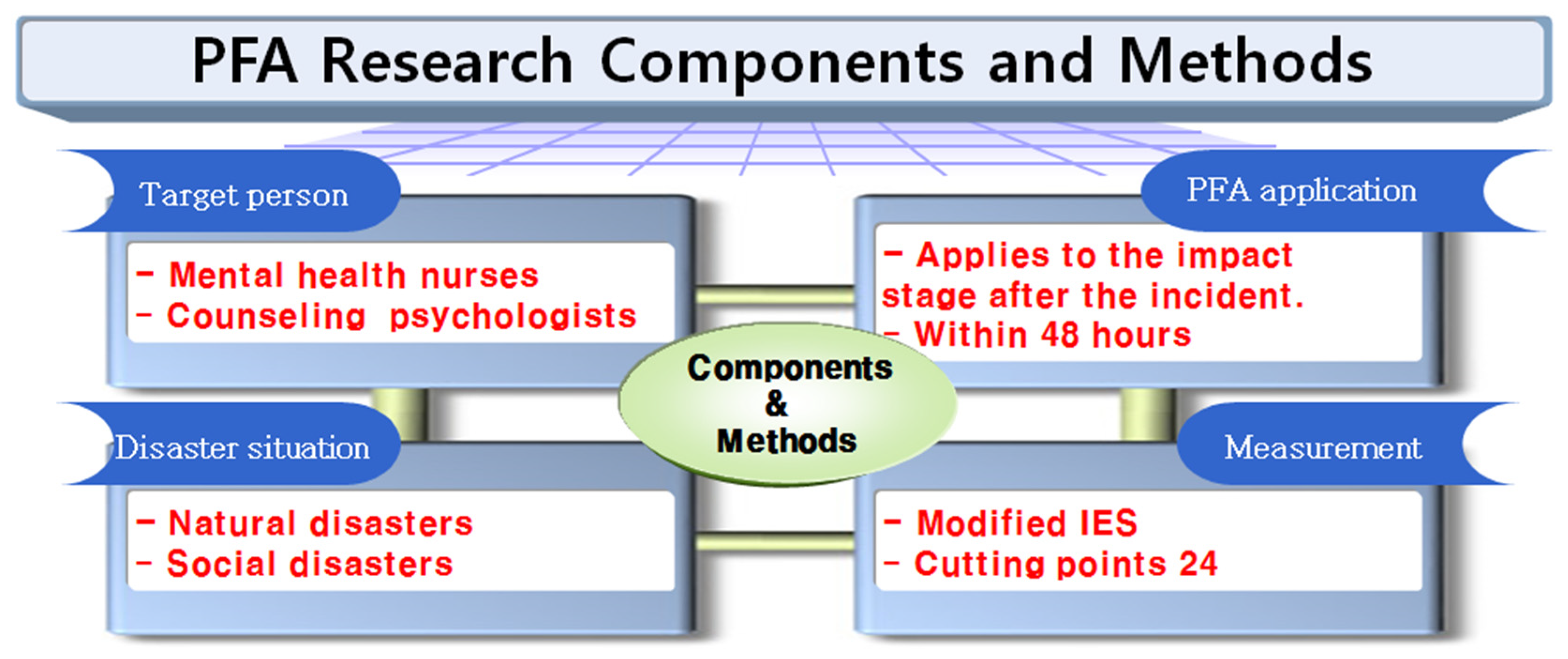

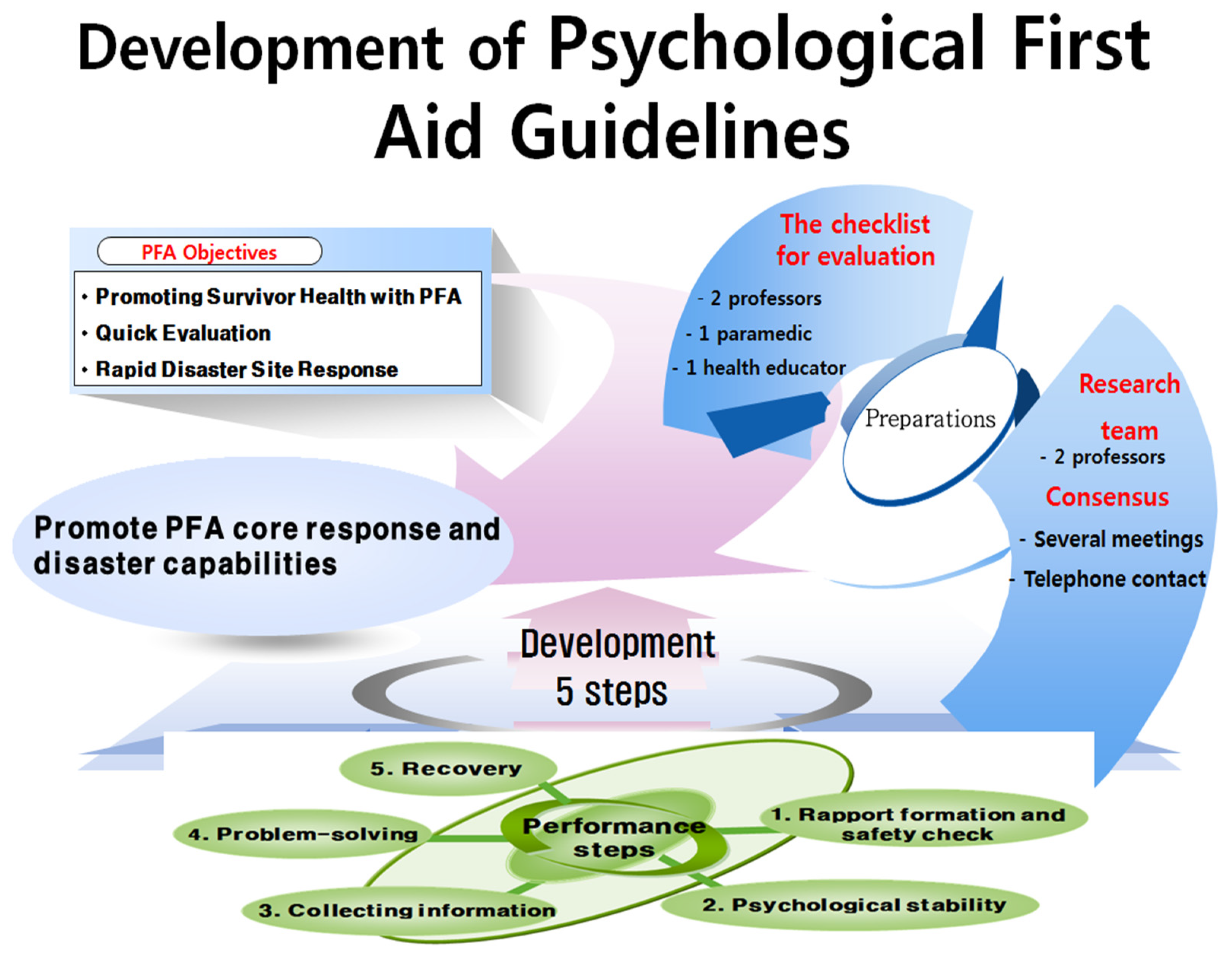

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Guideline Development Goals

2.2. PFA Guidelines Procedure

2.3. Checklist of Validation and Evaluation of Guidelines

3. Implementation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hechanova, M.R.M.; Manaois, J.O.; Masuda, H.V. Evaluation of an organiztion-based psychological first aid intervention. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2019, 28, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.I.; Choi, S.W.; Choi, Y.K.; Park, S.H.; You, S.E.; Baik, M.J.; Kim, H.; Hyun, J.; Seok, J.H. Effect of Korean Version of Psychological First Aid Training Program on Training Disaster Mental Health Service Provider. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2020, 59, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, C.M. Use of Psychological First Aid for Nurses. Nurs. Econ. 2020, 38, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Nursing Society. The Great Encyclopedia of Nursing Science; Korean Preliminary Research Institute: Seoul, Korea, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.H.; Ahn, H.E.; Choi, E.K.; Joo, H.S. Psychological First Aid for Disasters and Trauma, 2nd ed.; Hakjisa: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N.H. Narrative Analysis on Survivor´s Experience of Daegu Subway Fire Disaster–The Hypothetical Suggestions for Disaster Nursing Practice. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2005, 35, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Public Administration and Security. Establishment of Criteria for Psychological Stability and Social Response Support. Available online: https://www.mois.go.kr/frt/bbs/type010/commonSelectBoardArticle.do?bbsId=BBSMSTR_000000000008&nttId=78988 (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ripley, A. The Unthinkable: Who Survives When Disaster Strikes-and Why; Harmon: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, D.; Crompton, D.; Howard, A.; Stevens, N.; Metcalf, O.; Brymer, M.; Forbes, D. Skills for Psychological Recovery: Evaluation of a post-disaster mental health training program. Disaster Health 2014, 2, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, C.M.; Adams, R.M.; Peek, L. Incorporating mental health research into disaster risk reduction: An Online training module for the hazards and disaster workforce. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kang, H.S. The current status and implications of disaster psychological support system and crisis counseling program in the U.S. Korean J. Couns. 2015, 16, 513–536. [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead, G.S.; Karla, V. Sustainability of Psychological First Aid Training for the Disaster Response Workforce. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S381–S382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychological First Aid for First Responders. Tips for Emergency and Disaster Response Workers. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Psychological-First-Aid-for-First-Responders/NMH05-0210 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. The foundation of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice; Calhoun, L.G., Tedeschi, R.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Association: Mahwah, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M.J.; Wilner, N.; Alvarez, W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom. Med. 1979, 41, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weiss, D.S.; Marmar, C.R. The impact of event scale-revised. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keanc, T.M., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, H.J.; Kwon, T.W.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, T.H.; Choi, M.R.; Cho, S.J. A study on reliability and validity of the Korean version of impact of event scale-revised. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2005, 44, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Park, N.Y. The Effect of Unwanted Sex Consent on Post-Traumatic Growth and Impact of Event: The Moderating Effect of Cognitive Emotional Regulation Strategy. Master’s Thesis, Konyang University, NonSan, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, C.H. The effects of cognitive-behavioral group therpy for posttraumatic stress disorder for bus accidents victims. Korean J. Couns. Psychother. 2001, 13, 225–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S. A Case Study of Arts Therapy for Reducing of Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms and Anxiety, and Post-Traumatic Growth in Women Who Experienced the Psychological Trauma. Kor. Soc. Wellness 2020, 15, 33–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenema, T.G. ReadyRN E-Book: Handbook for Disaster Nursing and Emergency Preparedness, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Serviced. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/epic/pdf/SAMHSA_CDC_EPIC_PFA_508.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Allen, B.; Brymer, M.J.; Steinberg, A.M.; Vernberg, E.M.; Jacobs, A.; Speier, A.H.; Pynoos, R.S. Perceptions of psychological first aid among providers responding to Hurricanes Gustav and Ike. J. Trauma Stress 2010, 23, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, I.E.D.V. The medical interpreter mediation role: Through the lens of therapeutic communication. In Handbook of Research on Medical Interpreting; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Joung, J.; Park, Y. Exploring the Therapeutic Communication Practical Experience of Mental Health Nurses. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCTSN. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Available online: https://www.nctsn.org/treatments-and-practices/psychological-first-aid-and-skills-for-psychological-recovery/about-pfa (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Zehetmair, C.; Kaufmann, C.; Tegeler, I.; Kindermann, D.; Junne, F.; Zipfel, S.; Nikendei, C. Psychotherapeutic Group Intervention for Traumatized Male Refugees Using Imaginative Stabilization Techniques—A Pilot Study in a German Reception Center. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uhernik, J.A.; Husson, M.A. Psychological first aid: An evidence informed approach for acute disaster behavioral health response. Compelling Couns. Interv. VISTAS 2009, 200, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg, E.M.; Steinberg, A.M.; Jacobs, A.K.; Brymer, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Osofsky, J.D.; Ruzek, J.I. Innovations in disaster mental health: Psychological first aid. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2008, 39, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Shazer, S.; Dolan, Y.; Korman, H.; Trepper, T.; McCollum, E.; Berg, I.K. More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-Focused Brief Therapy; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M. Making positive change: A randomized study comparing solution-focused vs problem-focused coaching questions. J. Syst. Ther. 2012, 31, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Psychological First Aid Resources. Available online: https://www.apa.org/practice/programs/dmhi/psychological-first-aid/resources (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Azzollini, S.C.; Depaula, P.D.; Cosentino, A.C.; Bail Pupko, V. Applications of psychological first aid in disaster and emergency situations: Its relationship with decision-making. Athens. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 5, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Contents | Never | Sometimes | Usually | Often | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reminders of the situation at that time also bring back emotions. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | Have trouble keeping up my sleep. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | Other things led me to think about the incident. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | Felt sensitive and angry after that situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | Every time I think about the situation, I tried to avoid it because I was confused. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | Even if I try not to think, I remember the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | Either the situation did not happen, or it did not feel real. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | I stayed away from reminders of the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | A video of the situation used to pop into my mind. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 | My nerves became sensitive and I was easily surprised. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11 | I tried not to think about the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 | I was still confused by the situation, but I endured it. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | My feelings for the situation were numb. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | There are times when I feel or act as if I were back in the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15 | It was hard to fall asleep after that situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16 | I felt a flood of strong feelings about the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17 | I tried to erase the situation from my memory. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18 | I had difficulty concentrating. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19 | Considering the situation, I reacted physically, such as sweating, breathing problems, dizziness, or heart palpitations. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20 | I had a dream about the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21 | I felt I was on guard and observed my surroundings. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22 | I tried not to talk about the situation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Performance Step | Step-By-Step PFA Achievement Objectives | What to Do with the Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 1. First rapport formation and safety check | Psychologist’s introduction and confidentiality | Recognize that they are an authorized expert, respecting confidentiality. |

| Physical and psychological safety checks |

| |

| Check safety from incident stimuli |

| |

| 2. Psychological stability | Recalling a safe place |

|

| ||

| Psychological container techniques |

| |

| Exploring positive statements |

| |

| 3. Collecting information | The nature and severity of disasters and traumatic events. |

|

| Loss and guilt |

| |

| Concerns about subsequent threats immediately after the incident |

| |

| Availability of social resources |

| |

| 4. Problem-solving | See what you need right now |

|

| Develop specific action plans |

| |

| Utilization of social-support systems |

| |

| 5. Recovery | Think of yourself recovering | Check the resources I have |

| Ask questions about the happy future ahead. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, E.-Y.; Han, S.-W. Development of Psychological First Aid Guidelines for People Who Have Experienced Disasters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10752. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010752

Kim E-Y, Han S-W. Development of Psychological First Aid Guidelines for People Who Have Experienced Disasters. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10752. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010752

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun-Young, and Seung-Woo Han. 2021. "Development of Psychological First Aid Guidelines for People Who Have Experienced Disasters" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10752. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010752