Environmental Stressors Suffered by Women with Gynecological Cancers in the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Expensive essential infrastructure showing signs of advanced deterioration (e.g., water, energy, and transportation). According to recent reports, the total investment in infrastructure has been trending down for the last 18 years.

- One of the highest rates of unemployment in the US [19].

- The highest rates of the population living below poverty level in the US (43.1% persons in poverty) [19].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Focus Groups GYN Cancer Patients: Study Design and Population

2.2.2. Key Informants (Health Providers and Administrators)

2.2.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Qualitative Findings

3.2. Stressors in the Aftermath of Hurricane María

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Méndez-Lázaro, P. Potential impacts of climate change and variability on public health. J. Geol. Geosci. 2012, 1, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Lázaro, P.; Nieves-Santiago, A.; Miranda-Bermudez, M.; Rivera-Gutiérrez, R.; Peña-Orellana, M.; Padilla-Elías, N.; Colon-Bosques, E. Geografía de la Salud sin Fronteras. In Capitulo XII, Enfoque Geográfico de la Evolución de Riesgos Naturales y sus Posibles Impactos en la Salud Publica de Puerto Rico (1986–2011); Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México: Toluca, Mexico, 2014; ISBN 978-607-9343-67-5 (versión impresa)/978-607-9343-69-9 (versión digital). [Google Scholar]

- Orengo-Aguayo, R.; Stewart, R.W.; de Arellano, M.A.; Suárez-Kindy, J.L.; Young, J. Disaster exposure and mental health among Puerto Rican youths after Hurricane Maria. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scaramutti, C.; Salas-Wright, C.O.; Vos, S.R.; Schwartz, S.J. The Mental Health Impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico and Florida. 2019. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30696508/ (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Bell, S.A.; Abir, M.; Choi, H.; Cooke, C.; Iwashyna, T. All-cause hospital admissions among older adults after a natural disaster. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 71, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C. The Hurricane Katrina Community Advisory Group. Hurricane Katrina’s impact on the care of survivors with chronic medical conditions. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.A.; Glover, R.; Huang, Y. Epidemiologic Assessment of the Impact of Four Hurricanes—Florida, 2004. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/201604 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Ozaki, A.; Nomura, S.; Leppold, C.; Tsubokura, M.; Tanimoto, T.; Yokota, T.; Saji, S.; Sawano, T.; Tsukada, M.; Morita, T.; et al. Breast cancer patient delay in Fukushima, Japan following the 2011 triple disaster: A long-term retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David-West, G.; Musa, F.; Frey, M.K.; Boyd, L.; Pothuri, B.; Curtin, J.P.; Blank, S.V. Cross-sectional study of the impact of a natural disaster on the delivery of gynecologic oncology care. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2015, 9, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, H.; Aguirre, B.E. Hurricane Katrina and the healthcare infrastructure: A focus on disaster preparedness, response, and resiliency. Front. Health Serv. Manag. 2006, 23, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.; Franklin, R.C.; Burkle, F.M.; Aitken, P.; Smith, E.; Watt, K.; Leggat, P. Identifying and describing the impact of cyclone, storm and flood related disasters on treatment management, care and exacerbations of non-communicable diseases and the implications for public health. PLoS Curr. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loehn, B.; Pou, A.M.; Nuss, D.W.; Tenney, J.; McWhorter, A.; Dileo, M.; Kakade, A.C.; Walvekar, R.R. Factors affecting access to head and neck cancer care after a natural disaster: A post-Hurricane Katrina survey. Head Neck 2011, 33, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurricane MARIA. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2017/al15/al152017.update.09201034.shtml (accessed on 8 May 2020).

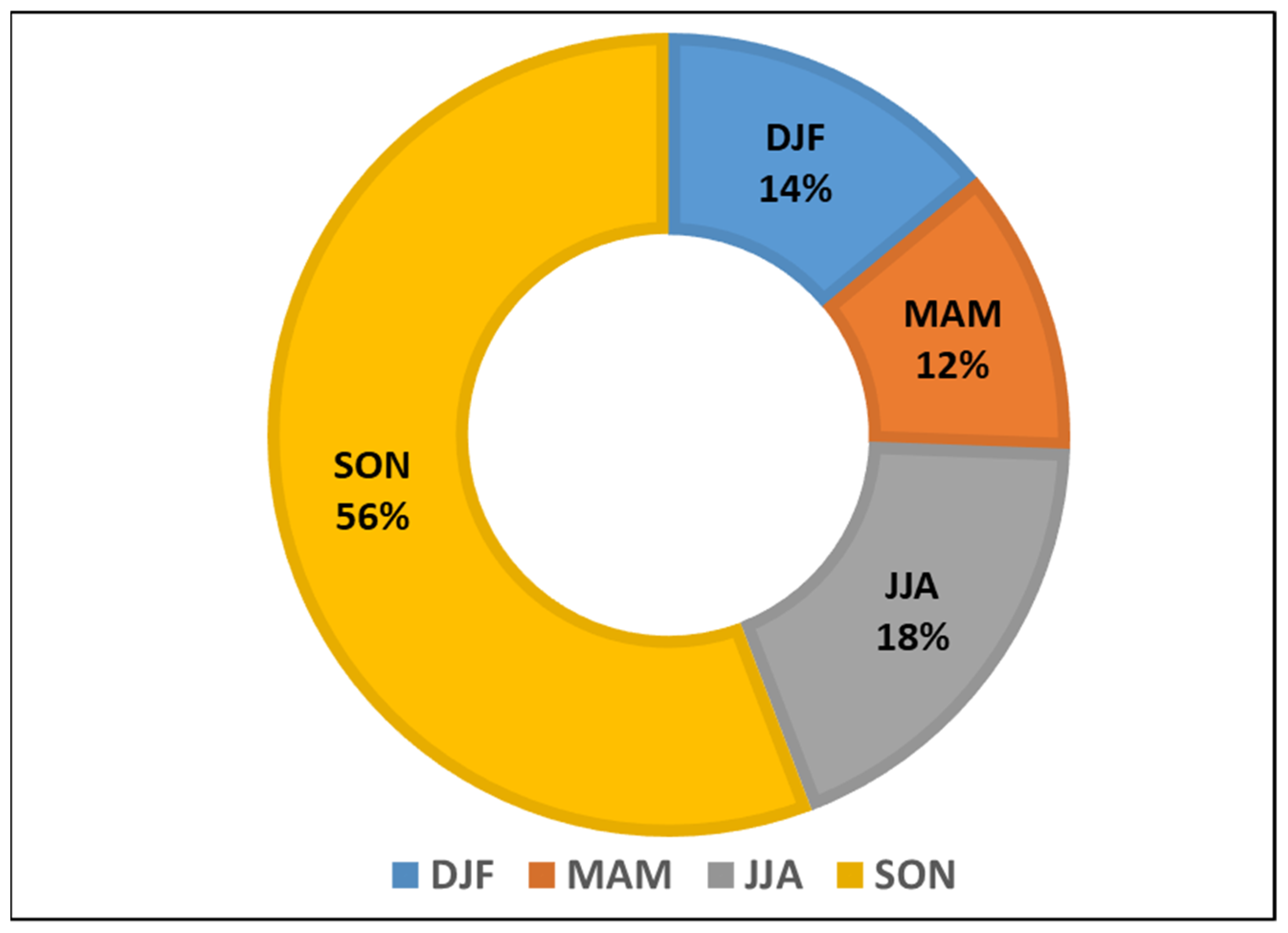

- Ramos-Scharrón, C.E.; Arima, E. Hurricane María’s precipitation signature in Puerto Rico: A conceivable presage of rains to come. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15612–15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessette-Kirton, E.K.; Cerovski-Darriau, C.; Schulz, W.H.; Coe, J.A.; Kean, J.W.; Godt, J.W.; Thomas, M.A.; Hughes, K.S. Landslides triggered by Hurricane Maria: Assessment of an extreme event in Puerto Rico. GSA Today 2019, 29, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Pol, E.; Navarro, O. (Eds.) Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mayol-García, Y.H. Pre-hurricane linkages between poverty, families, and migration among Puerto Rican-origin children living in Puerto Rico and the United States. Popul. Environ. 2020, 42, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Quick Facts: Puerto Rico. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Puerto Rico’s Department of Health, Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Division. Puerto Rico Chronic Disease Action Plan 2014–2020. Available online: https://www.iccp-portal.org/sites/default/files/plans/Puerto Rico Chronic Disease Action Plan English.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Rivera, F.I. Puerto Rico’s population before and after Hurricane Maria. Popul. Environ. 2020, 42, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Berríos, N.L.; Aponte-González, F.; Archibald, W. U.S. Caribbean. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 809–871. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Lázaro, P.; Peña-Orellana, M.; Padilla-Elías, N.; Rivera-Gutiérrez, R. The impact of natural hazards on population vulnerability and public health systems in tropical areas. J. Geol. Geosci. Cit. 2014, 3, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro, P.M.; Martínez-Sánchez, O.; Méndez-Tejeda, R.; Rodríguez, E.; Cortijo, E.M.A.N.S. Extreme heat events in San Juan Puerto Rico: Trends and variability of unusual hot weather and its possible effects on ecology and society. J. Climatol. Weather Forecast. 2015, 3, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FEMA.gov. Disaster Declarations Summaries—v1. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/openfema-data-page/disaster-declarations-summaries-v1 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Picou, J.S.; Nicholls, K.; Guski, R. Environmental stress and health. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 804–808. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, W.; Rodríguez, H. Population composition, migration and inequality: The influence of demographic changes on disaster risk and vulnerability. Soc. Forces 2008, 87, 1089–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Hardy, R.D.; Lazrus, H.; Mendez, M.; Orlove, B.; Rivera-Collazo, I.; Roberts, J.T.; Rockman, M.; Warner, B.P.; Winthrop, R. Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: A social science review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lock, S.; Rubin, G.J.; Murray, V.; Rogers, M.B.; Amlot, R.; Williams, R. Secondary stressors and extreme events and disasters: A systematic review of primary research from 2010–2011. PLoS Curr. 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, A.; Percy, C.; Jack, A.; Shanmugaratnam, K.; Sobin, L.; Parkin, M.; Whelan, S. ICD-O International Classification of Diseases for Oncology First Revision. 2013. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/96612/9789241548496_eng.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Ryan, B.J.; Franklin, R.C.; Burkle, F.M.; Smith, E.C.; Aitken, P.; Watt, K.; Leggat, P.A. Ranking and prioritizing strategies for reducing mortality and morbidity from noncommunicable diseases post disaster: An Australian perspective. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toner, E.S.; McGinty, M.; Schoch-Spana, M.; Rose, D.; Watson, M.; Echols, E.; Carbone, E.G. A community checklist for health sector resilience informed by hurricane sandy. Health Secur. 2017, 15, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daymet. Daily Surface Weather Data on a 1-km Grid for North America, Version 4. Available online: https://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dsviewer.pl?ds_id=1840 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Liu, W.; Qdaisat, A.; Lopez, G.; Narayanan, S.; Underwood, S.; Spano, M.; Reddy, A.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yeung, S.-C.; et al. Acupuncture for hot flashes in cancer patients: Clinical characteristics and traditional chinese medicine diagnosis as predictors of treatment response. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, E.; Schirru, A.; di Perri, M.C.; Bonuccelli, U.; Maestri, M. Insomnia and hot flashes. Maturitas 2019, 126, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-Y.; Jotwani, A.C.; Lai, Y.-H.; Jensen, M.P.; Syrjala, K.L.; Fann, J.R.; Gralow, J. Hot flashes in breast cancer survivors: Frequency, severity and impact. Breast 2016, 27, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kishore, N.; Marqués, D.; Mahmud, A.; Kiang, M.V.; Rodriguez, I.; Fuller, A.; Ebner, P.; Sorensen, C.; Racy, F.; Lemery, J.; et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos-Burgoa, C.; Sandberg, J.; Suarez, E.; Goldman-Hawes, A.; Zeger, S.; Garcia-Meza, A.; Pérez, C.M.; Estrada-Merly, N.; Colón-Ramos, U.; Nazario, C.M. Differential and persistent risk of excess mortality from Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico: A time-series analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e478–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrera, R.; Felix, G.; Acevedo, V.; Amador, M.; Rodriguez, D.; Rivera, L.; Gonzalez, O.; Nazario, N.; Ortiz, M.; Muñoz-Jordan, J.L.; et al. Impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on aedes aegypti populations, aquatic habitats, and mosquito infections with dengue, chikungunya, and zika viruses in Puerto Rico. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norovirus Outbreak among Evacuees from Hurricane Katrina—Houston, Texas, September 2005. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5440a3.htm (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Infectious Disease and Dermatologic Conditions in Evacuees and Rescue Workers after Hurricane Katrina—Multiple States. 2005. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5438a6.htm (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Pine, J. Hurricane Katrina and oil spills: Impact on coastal and ocean environments. Oceanography 2006, 19, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, J.D.; Osofsky, H.J. Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf Oil Spill: Lessons learned about short-term and long-term effects. Int. J. Psychol. 2021, 56, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, R.; Ellis, A.; Torres-Delgado, E.; Tanzer, R.; Malings, C.; Rivera, F.; Morales, M.; Baumgardner, D.; Presto, A.; Mayol-Bracero, O.L. Air quality in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria: A case study on the use of lower cost air quality monitors. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2018, 2, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yishan, L.; Sevillano-Rivera, M.; Jiang, T.; Li, G.; Cotto, I.; Vosloo, S.; Carpenter, C.M.; Larese-Casanova, P.; Giese, R.W.; Helbling, D.E.; et al. Impact of Hurricane Maria on drinking water quality in Puerto Rico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9495–9509. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Lázaro, P.A.; Pérez-Cardona, C.M.; Rodríguez, E.; Martínez, O.; Taboas, M.; Bocanegra, A.; Méndez-Tejeda, R. Climate change, heat, and mortality in the tropical urban area of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Lázaro, P.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Otis, D.; McCarthy, M.J.; Rodríguez, E. A heat vulnerability index to improve urban public health management in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Register. Information Collection: Post-Hurricane Research and Assessment of Agriculture, Forestry, and Rural Communities in the U.S. Caribbean. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/09/27/2018-20986/information-collection-post-hurricane-research-and-assessment-of-agriculture-forestry-and-rural (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Uriarte, M.; Thompson, J.; Zimmerman, J.K. Hurricane María tripled stem breaks and doubled tree mortality relative to other major storms. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maimaitiyiming, M.; Ghulam, A.; Tiyip, T.; Pla, F.; Latorre-Carmona, P.; Halik, Ü.; Sawut, M.; Caetano, M. Effects of green space spatial pattern on land surface temperature: Implications for sustainable urban planning and climate change adaptation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 89, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biggs, R.; Schlüter, M.; Schoon, M.L. (Eds.) Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; p. 290. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, M.S.; Carter, R.; Kish, J.K.; Gronlund, C.J.; White-Newsome, J.L.; Manarolla, X.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.D. Preventing heat-related morbidity and mortality: New approaches in a changing climate. Maturitas 2009, 64, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raymond, C.; Matthews, T.; Horton, R.M. The emergence of heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaw1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradovich, N.; Migliorini, R.; Mednick, S.C.; Fowler, J.H. Nighttime temperature and human sleep loss in a changing climate. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1601555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

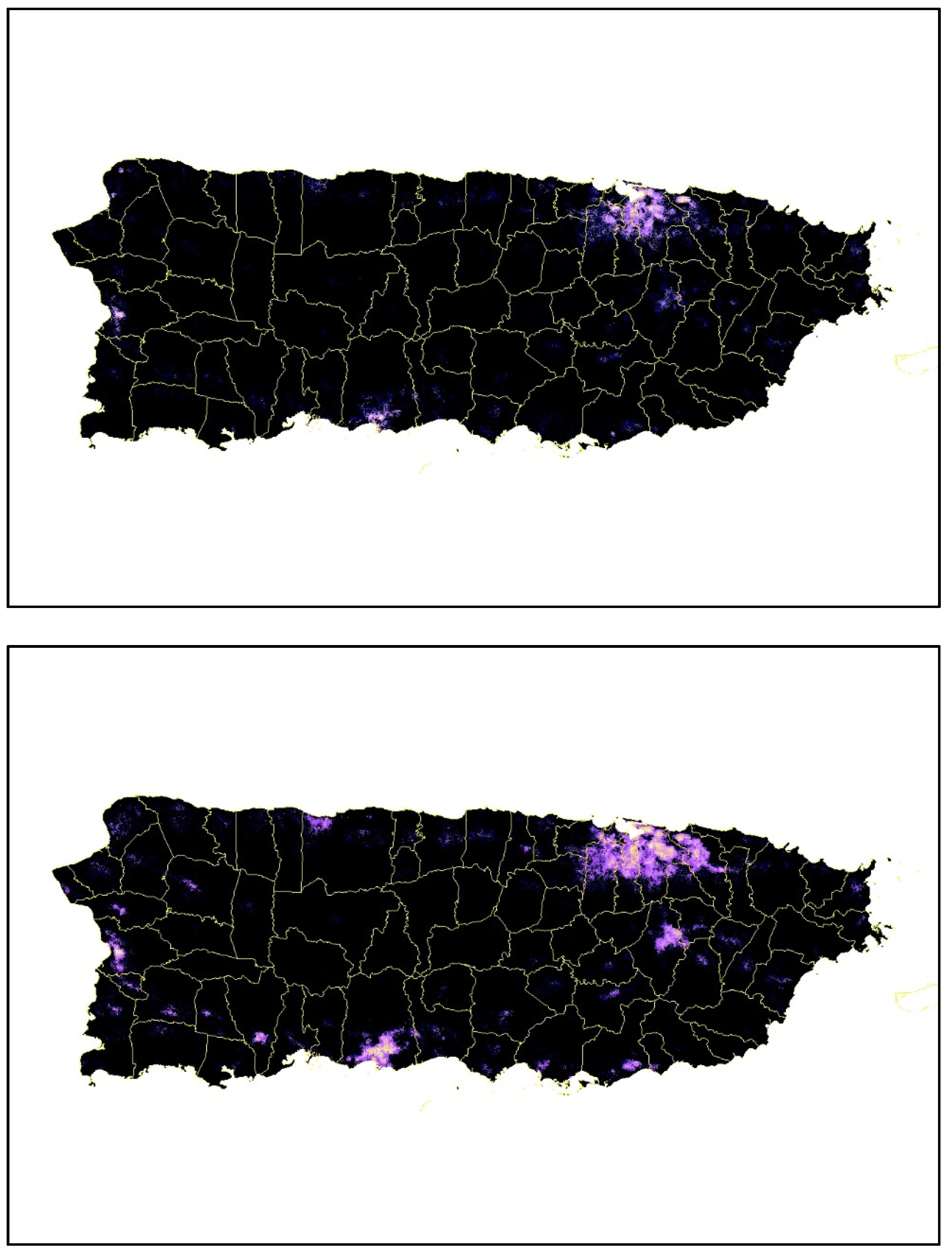

- Román, M.O.; Stokes, E.C.; Shrestha, R.; Wang, Z.; Schultz, L.; Carlo, E.A.S.; Sun, Q.; Bell, J.; Molthan, A.; Kalb, V.; et al. Satellite-based assessment of electricity restoration efforts in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.P.; Calo, W.A.; Mendez-Lazaro, P.; García-Camacho, S.; Mercado-Casillas, A.; Cabrera-Márquez, J.; Tortolero-Luna, G. Strengthening resilience and adaptive capacity to disasters in cancer control plans: Lessons learned from Puerto Rico. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1290–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Code | Code Definition | Absolute Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Informants (Health Providers and Administrators | Focus Groups (GYN Cancer Patients) | Total | ||

| L5.B Secondary Stressor | Stressors not inherent to the meteorological phenomenon. Secondary stressors could be those occurring during the aftermath of a climate-related disaster. Attributable or partially attributable to the disaster. | 86 | 73 | 159 |

| L5.D Physical/Environment Psychosocial Stressor | Experienced by women after the hurricanes. Evacuations, being displaced outside the home, transportation difficulties, time without electricity, telecommunications, water, availability of a power plant, damage to the home, access to materials and supplies, food, distance from the home to the clinic, and security. It is a person’s reaction to a specific situation in which a set of environmental variables are present whose disposition and intensity make them perceived as aversive. | 32 | 53 | 85 |

| L5.E Psychosocial Stressor of Health Care Systems | Experienced by women after the hurricanes. Lack of available health services. | 48 | 32 | 80 |

| Focus Groups: Cancer Patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Code ID | Original Version (Spanish) | English Version |

| D 22: 26 Transcription, Focus Group No. 3 | “…el calor estaba chispeante, pero tu tienes que pensar, que tu no puedes dormir bajo 4 o 5 paredes de cemento, porque el calor no hay manera de sacarlo. Así que tienes que tener la alternativa de dormir afuera. Yo dormí en la terraza!” | “…the heat was sparkling, but you have to think that you cannot sleep under four or five concrete walls because there is no way to get rid of the heat. Therefore, you have to have the alternative of sleeping outside. I slept on the terrace!” |

| D 21: 24 Transcription, Focus Group No. 1 | “Yo lloraba, hasta cuándo no vamos a tener luz, era bien frustrante! Y chequeándola a ver si estaba respirando, porque mi miedo era que por tanta calor le diera un bajón de azúcar y uno durmiendo. Y entonces yo la tocaba y a veces no la veía y era como que estaba respirando y yo ok. Pero fue bien frustrante.” | “I was crying, until when we will not have electricity, it was very frustrating! And checking her to see if she was breathing because my fear was that because of so much heat, she could have a low sugar episode and me sleeping. And then I would touch her, and sometimes I didn’t see her, and it was like she was breathing, and I was ok. But it was very frustrating.” |

| D 29: 25 Transcription, Focus Group No. 2: | “Pues si yo no tenía planta, claro que había calor! De hecho fíjate, llegaba un momento en donde uno…no tengo malos recuerdos de esa…O sea lo único que malo es lo de las plantas, (todos: el olor) las emisiones, es lo único, pero si a veces de noche uno no podía dormir por el calor, es verdad.” | “Well, if I didn’t have a generator, of course, it was hot! In fact, look, there came a time when one … I don’t have bad memories of that … I mean the only bad thing is the thing of the generators, (all: the smell) the emissions, it’s the only thing, but yes, sometimes at night one could not sleep because of the heat, it is true.” |

| D 4: 27 Transcription, Focus Group No. 4 | “Los mosquitos y el calor -fue bien difícil -yo no dormía casi” | “Mosquitoes and heat -It was very difficult -I hardly slept” |

| D 29: 25 Transcription, Focus Group No. 2 | “Pienso que le hubiese hecho caso a mi padre, de haber comprado la planta a tiempo, antes del huracán- antes del huracán! Y ese revolú de estar buscando agua, de que mi vecina llegara para conectar la nevera y más que nada las emisiones. Yo diría que eso fue lo más estrés que a mí me dio, siempre estaba viendo, y mi hijo; “por dónde viene el viento?, mira a ver, identifica. Okey, cierra estas ventanas! Después vuelve y abre, okey ahora vamos a cerrar las otras.” No dormía, como usted preguntó. No se dormía, por el calor. El calor era una cosa…yo no se si ustedes se acuerdan que hubo par de días que el calor, a menos que bueno si usted estaba durmiendo con aire pues (rien) - pero el calor fue una cosa bien intensa, bien intensa, yo vivo en Caguas” | “I think I would have listened to my father, of having had the generator on time, before the hurricane—before the hurricane! And that scramble of being looking for water, that my neighbor came to connect the refrigerator and more than anything the emissions. I would say that was the most stress that gave me, I was always watching, and my son; “Where does the wind come from? Look to see, identify. Okay, close these windows! Then come back and open, okay, now we are going to close the others. “ I wasn’t sleeping, as you asked. You couldn’t sleep because of the heat. The heat was one thing … I don’t know if you remember that there were a couple of days in which the heat, unless well if you were sleeping with air conditioning, then (group laughs) - but the heat was a very intense, very intense thing, I live in Caguas” |

| Key Informant Interviews | ||

| D 19: 18 Interview Transcription No. 18 | “Acuérdate que los pacientes que están (en tratamiento) de quimioterapia sufren mucho de calores, y hot flashes, muchas veces sudan de más (mucho), y están enfermos. Algunos vomitan, y al no tener la luz (electricidad) ni un abanico para refrescarse cuando uno se siente mal. (Tener) Hielo para refrescarse por dentro, eso es (de) lo que más se quejaron.” | “Remember that patients who are undergoing chemotherapy suffer a lot from heats and hot flashes; they sweat more (often), and they are sick. Some of them vomit, and not even having (electricity) a fan to cool off when you feel sick is not comfortable. Not having Ice to cool your organism inside, that’s what patients complained the most.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Méndez-Lázaro, P.A.; Bernhardt, Y.M.; Calo, W.A.; Pacheco Díaz, A.M.; García-Camacho, S.I.; Rivera-Lugo, M.; Acosta-Pérez, E.; Pérez, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, A.P. Environmental Stressors Suffered by Women with Gynecological Cancers in the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111183

Méndez-Lázaro PA, Bernhardt YM, Calo WA, Pacheco Díaz AM, García-Camacho SI, Rivera-Lugo M, Acosta-Pérez E, Pérez N, Ortiz-Martínez AP. Environmental Stressors Suffered by Women with Gynecological Cancers in the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111183

Chicago/Turabian StyleMéndez-Lázaro, Pablo A., Yanina M. Bernhardt, William A. Calo, Andrea M. Pacheco Díaz, Sandra I. García-Camacho, Mirza Rivera-Lugo, Edna Acosta-Pérez, Naydi Pérez, and Ana P. Ortiz-Martínez. 2021. "Environmental Stressors Suffered by Women with Gynecological Cancers in the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111183

APA StyleMéndez-Lázaro, P. A., Bernhardt, Y. M., Calo, W. A., Pacheco Díaz, A. M., García-Camacho, S. I., Rivera-Lugo, M., Acosta-Pérez, E., Pérez, N., & Ortiz-Martínez, A. P. (2021). Environmental Stressors Suffered by Women with Gynecological Cancers in the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and María in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111183