Reduction in Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patient on Clozapine Infected with COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

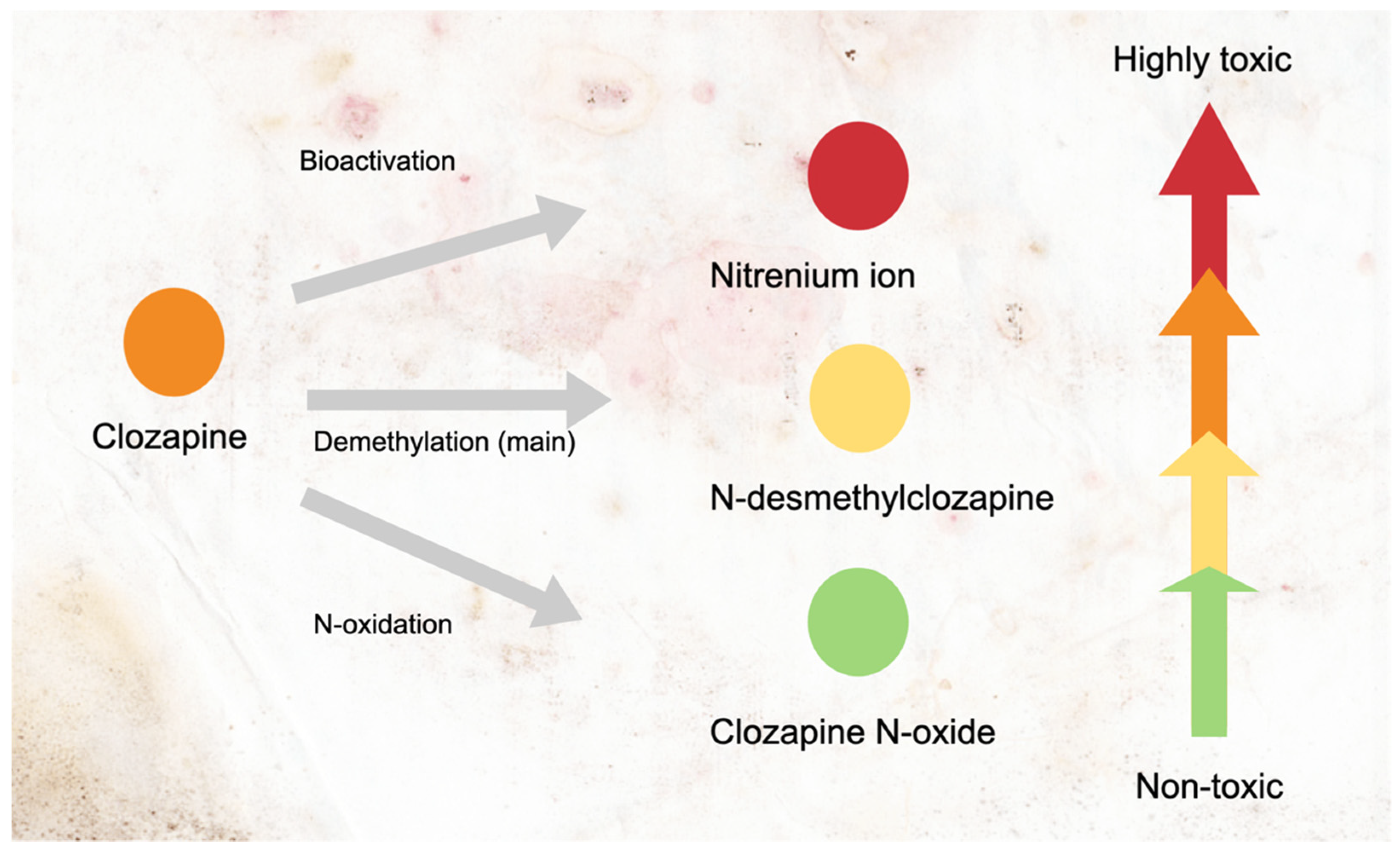

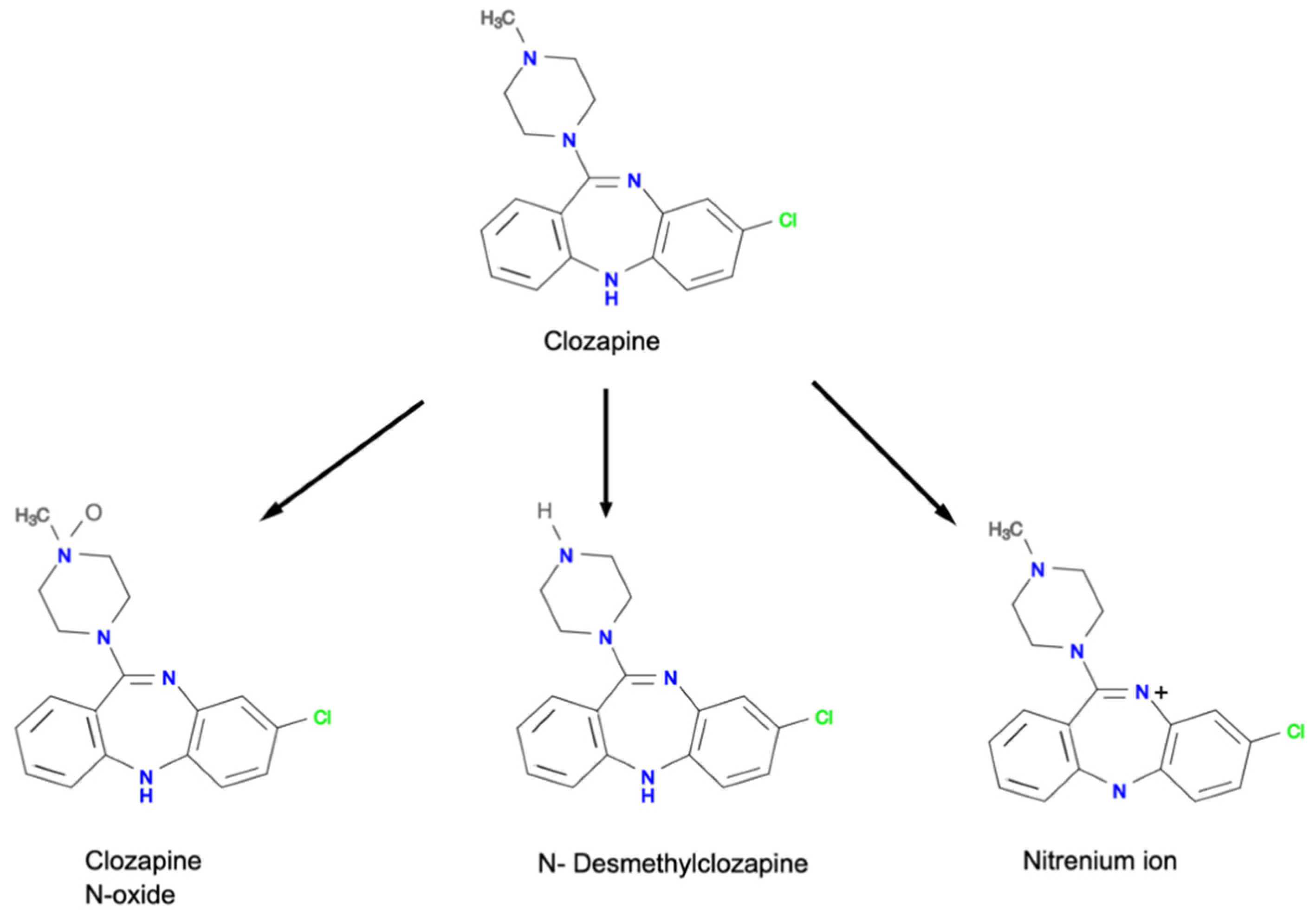

2. The Mechanisms of Clozapine-Induced Neutropenia

3. COVID-19 Infection and Neutrophil Count in Patients on Clozapine Treatment

3.1. Evidence from Case Series

3.2. Evidence from Case Report

3.3. Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, D.M. Clozapine for Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Still the Gold Standard? CNS Drugs 2017, 31, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khokhar, J.Y.; Henricks, A.M.; Sullivan, E.D.; Green, A.I. Unique Effects of Clozapine: A Pharmacological Perspective. Adv. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, J. The history of clozapine and its emergence in the US markett: A review and analysis. Hist. Psychiatry 2007, 18, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroup, T.; Gerhard, T.; Crystal, S.; Huang, C.; Olfson, M. Comparative Effectiveness of Clozapine and Standard Antipsychotic Treatment in Adults with Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.; Honigfeld, G.; Singer, J.; Meltzer, H. Clozapine for the Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenic. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988, 45, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijovic, A.; MacCabe, J.H. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 2477–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.; Dean, B. Clozapine bioactivation induces dose-dependent, drug-specific toxicity of human bone marrow stromal cells: A potential in vitro system for the study of agranulocytosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Pirmohamed, M.; Naisbitt, D.J.; Maggs, J.L.; Park, B.K. Neutrophil cytotoxicity of the chemically reactive metabolite(s) of clozapine: Possible role in agranulocytosis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 283, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.; Pirmohamed, M.; Naisbitt, D.J.; Uetrecht, J.P.; Park, B.K. Induction of Metabolism-Dependent and -Independent Neutrophil Apoptosis by Clozapine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000, 58, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.; Barreto, S.; Chandavarkar, R. Clozapine Monitoring in Clinical Practice: Beyond the Mandatory Requirement. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2016, 14, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-H.; Zhong, X.-M.; Lu, L.; Zheng, W.; Wang, S.-B.; Rao, W.-W.; Wang, S.; Ng, C.; Ungvari, G.S.; Wang, G.; et al. The prevalence of agranulocytosis and related death in clozapine-treated patients: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychol. Med. 2019, 50, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskind, D.; Honer, W.G.; Clark, S.; Correll, C.U.; Hasan, A.; Howes, O.; Kane, J.M.; Kelly, D.L.; Laitman, R.; Lee, J.; et al. Consensus statement on the use of clozapine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020, 45, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, M.; Hussain, N.; Shoaib, H.; Kim, M.; Lynch, T.J. Hematological characteristics of patients in coronavirus 19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Commun. Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2020, 10, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Elalamy, I.; Kastritis, E.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Politou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Gerotziafas, G.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borges, L.; Pithon-Curi, T.C.; Curi, R.; Hatanaka, E. COVID-19 and Neutrophils: The Relationship between Hyperinflammation and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 8829674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Z.; Ji, J.; Wen, C. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: The Current Evidence and Treatment Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccorso, S.; Ricciardi, A.; Ouabbou, S.; Theleritis, C.; Ross-Michaelides, A.; Metastasio, A.; Stewart, N.; Mohammed, M.; Schifano, F. Clozapine, neutropenia and Covid-19: Should clinicians be concerned? 3 months report. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 13, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, S.; Taylor, D. The effect of COVID-19 on absolute neutrophil counts in patients taking clozapine. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 2045125320940935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, S.; Taylor, D. COVID-19 infection causes a reduction in neutrophil counts in patients taking clozapine. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2021, 46, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, S. Clozapine, agranulocytosis, and benign ethnic neutropenia. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lobach, A.R.; Uetrecht, J. Clozapine Promotes the Proliferation of Granulocyte Progenitors in the Bone Marrow Leading to Increased Granulopoiesis and Neutrophilia in Rats. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.; Kennar, R.; Uetrecht, J. Effect of Clozapine and Olanzapine on Neutrophil Kinetics: Implications for Drug-Induced Agranulocytosis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorn, C.F.; Müller, D.J.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. PharmGKB summary: Clozapine pathway, pharmacokinetics. Pharm. Genom. 2018, 28, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liégeois, J.F.; Zahid, N.; Bruhwyler, J.; Uetrecht, J. Hypochlorous acid, a major oxidant produced by activated neutrophils, has low effect on two pyridobenzazepine derivatives, JL 3 and JL 13. Arch. Pharm. 2000, 333, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Uetrecht, J.P. Clozapine is oxidized by activated human neutrophils to a reactive nitrenium ion that irreversibly binds to the cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 275, 1476–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Okhuijsen-Pfeifer, C.; Ayhan, Y.; Lin, B.D.; Van Eijk, K.R.; Bekema, E.; Kool, L.J.G.B.; Bogers, J.P.A.M.; Muderrisoglu, A.; Babaoglu, M.O.; Van Assche, E.; et al. Genetic Susceptibility to Clozapine-Induced Agranulocytosis/Neutropenia Across Ethnicities: Results from a New Cohort of Turkish and Other Caucasian Participants, and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Bull. Open 2020, 1, sgaa024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Weide, K.; Loovers, H.; Pondman, K.; Bogers, J.; Van Der Straaten, T.; Langemeijer, E.; Cohen, D.; Commandeur, J.; Van Der Weide, J. Genetic risk factors for clozapine-induced neutropenia and agranulocytosis in a Dutch psychiatric population. Pharm. J. 2016, 17, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettling, M.; Cascorbi, I.; Roots, I.; Mueller-Oerlinghausen, B. Genetic determinants of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: Recent results of HLA subtyping in a non-jewish caucasian sample. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.Z.; Summers, M.K.; Peterson, D.; Brauer, M.J.; Lee, J.; Senese, S.; Gholkar, A.; Lo, Y.-C.; Lei, X.; Jung, K.; et al. The STARD9/Kif16a Kinesin Associates with Mitotic Microtubules and Regulates Spindle Pole Assembly. Cell 2011, 147, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ai, J.; Druhan, L.J.; Loveland, M.J.; Avalos, B.R. G-CSFR Ubiquitination Critically Regulates Myeloid Cell Survival and Proliferation. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, S.; Hamshere, M.L.; Ripke, S.; Pardiñas, A.; Goldstein, J.I.; Rees, E.; Richards, A.L.; Leonenko, G.; Jorskog, L.F.; Chambert, K.D.; et al. Genome-wide common and rare variant analysis provides novel insights into clozapine-associated neutropenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 22, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pirmohamed, M.; Park, K. Mechanism of Clozapine-Induced Agranulocytosis: Current status of research and implications for drug development. CNS Drugs 1997, 7, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.; Bano, F.; Calcia, M.; McMullen, I.; Lam, C.C.S.F.; Smith, L.J.; Taylor, D.; Gee, S. Clozapine prescribing in COVID-19 positive medical inpatients: A case series. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 10, 2045125320959560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranshaw, T.; Harikumar, T. COVID-19 Infection May Cause Clozapine Intoxication: Case Report and Discussion. Schizophr. Bull. 2020, 46, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotson, S.; Hartvigsen, N.; Wesner, T.; Carbary, T.J.; Fricchione, G.; Freudenreich, O. Clozapine Toxicity in the Setting of COVID-19. Psychosomatics 2020, 61, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, X.; Dratcu, L. Clozapine in the Time of COVID-19. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Omata, Y.; Naito, M.; Ito, K. Blockade of Interleukin 6 Signaling Induces Marked Neutropenia in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: Figure 1. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 36, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dean, L. Clozapine therapy and CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4 genotypes. In Medical Genetics Summaries; Pratt, V.M., Scott, S.A., Pirmohamed, M., Esquivel, B., Kane, M.S., Kattman, B.L., Malheiro, A.J., Eds.; National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E.T. Impact of Infectious and Inflammatory Disease on Cytochrome P450–Mediated Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 85, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ma, Q.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.; Gao, G.; Liu, F.; et al. Profiling serum cytokines in COVID-19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, N.; Myles, H.; Xia, S.; Large, M.; Bird, R.; Galletly, C.; Kisely, S.; Siskind, D. A meta-analysis of controlled studies comparing the association between clozapine and other antipsychotic medications and the development of neutropenia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2019, 53, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| References | Population/Patient Characteristics | Duration and Dose of Clozapine | Location | ANC | Remarks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | During Infection | Post Infection | |||||

| Case series | |||||||

| Gee [18] | Thirteen patients with a mean of 48 years of age. The majority were women (69%), non-Caucasian (69%) and had comorbidities (85%). | Duration: Less than 18 weeks–more than 1 year (range) Dose: NA | South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. | 4.83 × 109/L | 4.24 × 109/L | 5.70 × 109/L | |

| Bonaccorso [17] | Ten patients with the median of 45.4 years of age. The majority were male (70%), of African descent (50%), and had some comorbidities. | Duration: 726.1 days (mean) Dose: 200–600 mg/day (range) | Highgate Mental Health Centre, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust. | 5.20 × 109/L | 4.13 × 109/L ↓ * | 5.28 × 109/L ↑ ** | The clozapine dose from one patient was reduced while another was stopped. |

| Gee [19] | Fifty-three patients with the age range between less than 20 years of age and more than 80 years of age. The majority were male (64%), non-Caucasian (64%), and had schizophrenia diagnoses (64%). | Duration: 4.6 years (mean) 12 days–28 years (range) Dose: 342 mg/day (mean) 50–800 mg/day (range) | Five centers under the London Mental Health Trusts. | 4.72 × 109/L | 3.83 × 109/L ↓* | 4.73 × 109/L | This datasets comprises Gee and Taylor [18] and Bonaccorso, et al. [17] with additional samples. A total of 36% of patients had their clozapine dose changed/stopped due to various reasons. |

| Case report | |||||||

| Butler [33] | A 62-year-old man (African descent) with schizoaffective disorder presented with delirium, fever, respiratory symptoms, and signs. However, the patient had a worsening respiratory condition and died of COVID-19 pneumonia. | Duration: Since late 2018 Dose: 600 mg daily | A university teaching hospital in London, 16 March–1 May 2020. | NA | 1.64 × 109/L (N) | NA (patient died) | Clozapine was withheld for less than 24 h then restarted at 400 mg ON. |

| Butler [33] | A 57-year-old woman (Caucasian) with treatment-resistant schizophrenia presented with hypoxia and hemodynamic instability. The patient was supported with a mechanical ventilator. Subsequently, the patient was in slow recovery at the time the article was written. | Duration: NA Dose: 350 mg daily | A university teaching hospital in London, 16 March–1 May 2020. | NA | 10.3 × 109/L ↑ | NA | Clozapine was stopped but retitrated on day 19. |

| Cranshaw [34] | A 38-year-old man with organic psychosis presented with respiratory signs and symptoms and clozapine toxicity signs (hypersalivation and myoclonus). The patient had elevated clozapine (0.73 mg/l) and norclozapine (0.31 mg/l) levels. | Duration: NA Dose: 325 mg daily | NA (UK) | NA | 1.26 × 109/L ↓ | NA | Clozapine was temporarily stopped due to significant lymphopenia. Uncomplicated recovery. |

| Dotson [35] | A 76-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder (bipolar-type) with recurrent catatonia on clozapine 300 mg ON and monthly ECT. The patient presented with catatonia. High clozapine levels on admission (1360 ng/mL). Concurrent use with tocilizumab. | Several years | NA | NA | 1.10 × 109/L ↓ | 4.00 × 109/L | |

| Dotson [35] | A 63-year-old woman with schizoaffective disorder (bipolar-type) on clozapine 50 mg OM/350mg ON, olanzapine 20 mg ON, citalopram 20 mg OD. The patient presented with confusion, nausea, ileus, severe hyponatremia with high clozapine levels on admission (1060 ng/mL). | NA | NA | NA | 14.97 × 109/L ↑ | NA | Clozapine was withheld for a week and was retitrated as her bowel function normalized. |

| Dotson [35] | A 53-year-old woman with schizophrenia on clozapine 250 mg ON. The patient presented with delirium, fever, and vomiting. She had high clozapine levels on admission (2154 ng/mL). Her ANC level was stable during her stay. The patient was eventually discharged. | Several years | NA | NA | 2.20 × 109/L (N) | NA | Clozapine dose was reduced. |

| Boland [36] | A 21-year-old man with treatment-resistant schizoaffective disorder on clozapine 850 mg ON and lithium 1.2 g ON for 18 months. He presented with fever, coryzal symptoms, high blood pressure, tachycardia, deranged renal profile. The patient eventually became well and was discharged. | 18 months | NA | 6.94 × 109/L (N) | NA | Clozapine was withheld for three days and then retitrated over five days to 600 mg daily. | |

| Gee [19] | A non-Caucasian woman in a 21–30 age group was diagnosed with COVID-19 infection (no further information provided). | Duration: 231 days Dose: NA | One of five centers under the London Mental Health Trusts. | >2.50 × 109/L | 1.2–1.4 × 109/L (Day 8–9) ↓ | NA (reported as resolved) | Clozapine was withheld for 24 h. |

| Gee [19] | An African descent man in the 51–60 age group with a history of moderate neutropenia (0.7 × 109/L ANC) when he was under critical care due to a motor vehicle accident. | Duration: 520 days Dose: NA | NA | 0.9 × 109/L (Day 5), 1.2–2.1 × 109/L (Day 6–8) ↓ | >2.0 × 109/L | Clozapine was withheld (no specific duration reported) but then restarted. | |

| Gee [19] | A Caucasian man in a 31–40 age group. | Duration: 339 days Dose: NA | NA | >2.5 × 109/L (until day 5) 1.2 × 109/L (Day 6) ↓ | 2.7 × 109/L (Day 8) | Clozapine was withheld but restarted on day 10. | |

| Gee [19] | A non-Caucasian man in a 21–30 age group. | Duration: 67 days Dose: NA | ≥2.9 × 109/L | 0.5–0.9 × 109/L ↓ | NA (but resolved on day 38) | Clozapine treatment stopped. | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramli, F.F.; Ali, A.; Syed Hashim, S.A.; Kamisah, Y.; Ibrahim, N. Reduction in Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patient on Clozapine Infected with COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111289

Ramli FF, Ali A, Syed Hashim SA, Kamisah Y, Ibrahim N. Reduction in Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patient on Clozapine Infected with COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111289

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamli, Fitri Fareez, Adli Ali, Syed Alhafiz Syed Hashim, Yusof Kamisah, and Normala Ibrahim. 2021. "Reduction in Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patient on Clozapine Infected with COVID-19" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111289

APA StyleRamli, F. F., Ali, A., Syed Hashim, S. A., Kamisah, Y., & Ibrahim, N. (2021). Reduction in Absolute Neutrophil Counts in Patient on Clozapine Infected with COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111289