LGBTQ+ Psychosocial Concerns in Nursing and Midwifery Education Programmes: Qualitative Findings from a Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- What content is delivered within nursing and midwifery pre-registration programmes to address the psychosocial concerns of LGBTQ+ people?

- What are the barriers to the inclusion of LGBTQ+ health content within nursing and midwifery pre-registration programmes?

- What are the areas of best education practice regarding the inclusion of LGBTQ+ health concerns in nursing and midwifery pre-registration programmes?

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Study Participants

3. Data Collection

Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Variable Programme Content

“As well as a passion for LGBTQIA health, the concepts of social justice and intersectionality are very at the forefront of my thinking. When we started developing the programmes, I actually put forward the idea that we had… a module within adult nursing that specifically looked at social justice, using intersectionality and focused on the protected characteristics from the Equalities Act.”(Ryan)

“I personalised it and I deliberately personalised it so that they could really appreciate quite how alienated that would be and then from there people understanding the damage of heteronormative language and the forms and the attitudes… Obviously to be constructively aligned within the programme I have to do some sessions about the impact on others… I talk about diversity and their pre-existing mental health. One of the areas that I explore is LGBT+ communities and also LGBT+ midwives.”(Charlie)

“I am 59 and I am a gay man but for somebody who is 59 and for a woman who’s 19, who’s a lesbian, my experience of being gay is very different from hers, or could be, or it could be somebody in their 70′s”.(Alex)

“Because it is not required to be built into the programme, it doesn’t exist. Again, something that is policy driven and the nursing and midwifery regulators could ensure through their monitoring and programme review processes is visible and included.”(Lee)

4.2. Developing Programme Consistency

“Usually it’s classroom, lectures, blended learning, some online things. All of them, service users were key. The mental health person, the nursing and the midwives were using service users to give their stories, and I have just told you I have done the same. Stories and service users are very key.”(Sam)

“We start with the concept and then we build towards the nursing practice implications. We find that really helps them embed it and really understand it…With the mental health study days that I do, again I turn that into talking to them about how do you support trans youth; how do you look for signs of gender dysphoria as opposed to somebody who is trans. Not every trans person has gender dysphoria. This idea of labelling everybody as dysphoric when that’s not necessarily everybody’s story.”(Ryan)

“I think we have got a very clear inclusion of trans in the curriculum now. I think that again is how society has shifted agendas.”(Finn)

“I was approached by the local perinatal mental health team… they brought up about training around LGBTQ because they said that we’ve got more people who are trans becoming pregnant and they are not having good experiences of maternity care, so we need to do some education on that. We had inclusion around LGBTQ issues, but we hadn’t included about trans people… we’re getting trans people become pregnant, but the staff aren’t prepared to support them. I know from talking with the LGBTQ forum they said that. They know that some trans people are reluctant to attend for ante-natal care because of the reaction they get which is upsetting for me really.”(Blake)

“I still think midwifery academics have got a way to go. Some of the language that we use makes assumptions about sexuality and this needs to change.”(Charlie)

“I think we have to be more open, be more open, and not assuming. And I’d say, really understand the psychosocial issues much further, particularly those who I find teach labour ward skills are still very medically focused. I think the whole concept of the psychosocial issues we need to address much more than we are doing.”(Blake)

4.3. Linking LGBTQ+ Health to Equality and Diversity

“It all comes under the umbrella of diversity. They are able to care for women with diverse needs. How diverse that is depends. We have got cultural-specific stuff, but it’s broad. Nothing LGBT specific.”(Blake)

“I spoke with our Equality and Diversity Student Services Lead, and we discussed how we could ensure that LGBT is more integrated into the curriculum… I said that I felt that it was really important it was embedded rather than an add on… the Programme Director makes sure that we are all mapped fully against the NMC Standards, but also against our equality plan.”(Finn)

“I think it is just really important that students see themselves reflected within the curriculum. And students see the patients that they are going to meet reflected within the curriculum. If your curriculum is traditional, it is whitewashed, everybody is heterosexual from a middle-class background, that kind of thing, it is not reflective of real life and it’s not reflective of your student population either.”(Chris)

“One of the issues coming up for trans people at the moment is for someone that’s transitioned earlier in life, and now if they have got dementia, it may mean that they don’t recognise their genitals or they wonder why they are being called by a name that wasn’t the name assigned at birth, that type of thing.”(Joe)

4.4. Barriers to Education Provision

4.4.1. Personal Confidence

“In many ways I don’t feel I was the right one. I got the job by being willing rather than having any great experience in the area… Sometimes I will say to the students, I’m not an expert in this field. I still to now struggle with the use of pronouns… Some of that may be the age I grew up in… Yes, that’s it, I’m not sure I’m necessarily the person to take it on because how well do I understand the issues… I don’t feel I’m the best person to teach here. I just appeared to be the only person who was willing to teach it at the beginning.”(Ray)

“I actually probably think it would be better coming from someone who is a member of the LGBTQ+ community. I feel a bit of a fraud trying to advocate for them… I think it can be something that some staff feel that they are not fully well equipped to deliver and can feel sometimes a little bit uncomfortable about.”(Chris)

4.4.2. Limited Knowledge and Skills of LGBTQ+ Issues and Needs

“I have brought my own experiences as a gay man, but I am very mindful that I am a gay man and not a lesbian or bisexual and I am still learning a lot, but I suppose I have my own insights.”(Alex)

“She [daughter] had gone into hospital and straightaway there was an assumption made that she was very heterosexual and when her partner turned up, they couldn’t bring themselves to use the word partner… Because of that and understanding quite how challenging that was to her mental health at a time where she was particularly vulnerable, that sort of informed my philosophy around how I was going to teach that.”(Charlie)

“We have a set of resources from service users and local members of the community who are happy to share their story and work with students. Literally at the moment I have got the YouTube video popped up and open… A gentleman who is now in his fifties who talks about his transition from female to male in his twenties and talks about the challenges with healthcare. I am reviewing that now and looking to get that integrated where I can.”(Lee)

“When I go down and see my daughter… I often meet a lot of her friends…They are often quite negative, her friends, because they have experienced bad situations. I can use that as a vehicle to address in my lectures. Sometimes I’ll say to them, you are making a really good point, do you mind if I talk about this conversation with my students. They always say yes. They always say yes, go ahead, fill your boots, I want this message to be heard.”(Charlie)

4.4.3. Identification and Availability of Networks

“I always love it if sessions like this could be delivered by people who identified with the group that they were talking about. But I do recognise actually we can’t always do that and as long as we have materials that are developed in a person-centred way in a way that reflects language that is positive and all that sort of stuff, I think we can work within it. But it’s not ideal.”(Ryan)

“It’s really important to get LGBTQ input into this wherever possible, but the challenge is how do you go about sourcing that when it’s still a sensitive issue for some.”(Lee)

4.5. Best Practice Examples

4.5.1. Skills Simulation

“… role play in relation to having somebody who is playing the part of somebody from the LGBT community whether that is the midwife, the birth partner, or the woman in the bed, and just to play it out in that respect.”(Jordon)

“We try to incorporate in a realistic way rather than throwing everything at them. As they work their way through a skills scenario for example in our skills lab, they will move from patient to patient and within that there may be a same sex parent, and then the other side, maybe a hetero-sexual person of colour with perhaps HIV. We integrate it.”(Finn)

“It was really seeing the ideas brought to life but in a safe environment, in a simulated environment, as opposed to being in practice meeting somebody and then putting their foot in it.”(Ryan)

“You could definitely use simulation to really explore in a safe environment what it means because I think a big part of it for both staff and students is they don’t want to offend. But by trying to avoid offending they remain silent so therefore people remain invisible. It’s how to think actually you are better off to be more sensitive and ask the questions in an inclusive manner. If you make some mistakes people will forgive you rather than not saying anything and therefore, we don’t see, we don’t hear, we don’t learn. Simulation would be perfect, absolutely perfect.”(Alex)

4.5.2. Linking in with Local Networks

“I decided that I needed to review what we were doing but I needed help with it, so I approached the LGBTQ forum in [local city] and had a really helpful meeting with them. They agreed to come and do some teaching for us… I have learned how open and helpful LGBTQ people are when you talk to them. They are very kind, and they don’t mind, you know, they are very open, and they don’t take offence when you make a blunder. That’s been nice and confidence building for me.”(Blake)

“We have a lady who was born a man and she has been quite vocal about the needs of the trans gender community, and she has been doing some sessions talking about language and inclusivity.”(Charlie)

4.5.3. LGBTQ+ Champions and Success

“They have just appointed a LGBT Champion for their programme development.”(Sam)

“We have had some students in our group that if it comes up, they will contribute to the conversation in class because I think students are much more open now than what they used to be. They are quite happy to talk about it and we can all learn as a result”(Jordon)

“Be open to the unlearning. Be open to the fact that wherever your position is, whatever you are, whatever your personal identities, you don’t know everybody’s lived experiences or different group’s experiences. Be open to hear it.”(Ryan)

“I always refer the students back to the Nursing and Midwifery Council’s Code for Professional Conduct. The very first section in there is on prioritising people. I get them to look at reading every sentence one by one and trying to view it through the lens of sexualities and gender orientations… Just normalise it, throw it in. If you are doing a course on whatever you are doing it on, make sure you get some case studies in there, different ones, lesbian people, gay people, trans people.”(Joe)

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy

5.2. Education

- Agender—having no gender

- Androgyne—somewhere in-between man or woman

- Bigender—two gender identities at the same time or interchangeably

- Demigirl/demiboy—not completely identifying as woman or man.

5.3. Practice Learning

- Be proactive in their approach to welcoming trans and non-binary service users to care.

- Always treat trans and non-binary patients in a respectful way, as they would other service users.

- When unsure about how to address a service user, begin by introducing themself with their own name and pronouns. Following on, the nurse or midwife can then politely and discreetly ask the person for their name and pronouns.

- Avoid disclosing a service user’s trans or non-binary status to anyone who does not need to know.

- Discuss issues relating to service user’s gender identity in private, and with care and sensitivity, such as how would they like parts of their body referred to and with appropriate language.

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Formby, E. How should we ‘care’ for LGBT+ students within higher education? Pastor. Care Educ. 2017, 35, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, R.; Daniel, H.; Cooney, T.G.; Engel, L.S. Envisioning a better US health care system for all: Coverage and cost of care. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172 (Suppl. 2), S7–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. Primary Health Care on the Road to Universal Health Coverage: 2019 Global Monitoring Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029040 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- McCartney, G.; Popham, F.; McMaster, R.; Cumbers, A. Defining health and health inequalities. Public Health 2019, 172, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, P.; Batty, G.D.; Stenholm, S.; Kawachi, I.; Hyde, M.; Goldberg, M.; Westerlund, H.; Vahtera, J.; Head, J. Socioeconomic inequalities in disability-free life expectancy in older people from England and the United States: A cross-national population-based study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Potts, L.; Robinson, E.J. Mental illness stigma after a decade of Time to Change England: Inequalities as targets for further improvement. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M.L. Health inequalities: A global perspective. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2017, 22, 2097–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, Y.; Baker, P.; Ismail, S.A.; Tillmann, T.; Bash, K.; Quantz, D.; Hillier-Brown, F.; Jayatunga, W.; Kelly, G.; Black, M.; et al. Going upstream–an umbrella review of the macroeconomic determinants of health and health inequalities. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeeman, L.; Sherriff, N.; Browne, K.; McGlynn, N.; Mirandola, M.; Gios, L.; Davis, R.; Sanchez-Lambert, J.; Aujean, S.; Pinto, N.; et al. A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) health and healthcare inequalities. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casey, L.S.; Reisner, S.L.; Findling, M.G.; Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Sayde, J.M.; Miller, C. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, C.H.; Bilgin, H.; Uluman, O.T.; Sukut, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Buzlu, S. A systematic review of the discrimination against sexual and gender minority in health care settings. Int. J. Health Serv. 2020, 50, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H.; Russell, S.T.; Hammack, P.L.; Frost, D.M.; Wilson, B.D. Minority stress, distress, and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: A US probability sample. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, S.N.; Crowe, M.; Harris, S. The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities’ mental health care needs and experiences of mental health services: An integrative review of qualitative studies. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinchcombe, A.; Wilson, K.; Kortes-Miller, K.; Chambers, L.; Weaver, B. Physical and mental health inequalities among aging lesbian, gay, and bisexual Canadians: Cross-sectional results from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Can. J. Public Health 2018, 109, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, M.; Bishop, M.D.; Martos, A.; Wilson, B.D.; Russell, S.T. Sexual minority people’s perspectives of sexual health care: Understanding minority stress in sexual health settings. Sex. Res. Soc. Pol. 2020, 17, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatchel, T.; Polanin, J.R.; Espelage, D.L. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: Meta-analyses and a systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 2, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, J.S.; Craig, S.L.; Austin, A. Trauma-informed and affirmative mental health practices with LGBTQ+ clients. Psychol. Serv. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, D.; Gilchrist, G. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among transgender adults: A systematic review. Addict. Behav. 2020, 111, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131-eng.pdf;jsessionid=8FFBC6447827BD72F925028C29C27AC8?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Joseph, B.; Joseph, M. The health of the health workers. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 20, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organisation. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Beech, J.; Bottery, S.; Charlesworth, A.; Evans, H.; Gershlick, B.; Hemmings, N.; Imison, C.; Kahtan, P.; McKenna, H.; Murray, R.; et al. Closing the Gap. Key Areas for Action on the Health and Care Workforce; The Health Foundation/Nuffield Trust/The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/closing-the-gap-key-areas-for-action-on-the-health-and-care-workforce (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Nursing and Midwifery Board for Ireland. Available online: https://www.nmbi.ie/Registration (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- McCann, E.; Brown, M. The inclusion of LGBT+ health issues within undergraduate healthcare education and professional training programmes: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 64, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCann, E.; Brown, M.; Hollins Martin, C.; Murray, K.; McCormick, F. The views and experiences of LGBTQ+ people regarding midwifery care: A systematic review of the international evidence. Midwifery 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, T.; Seibenhener, S.; Young, D. Incorporating health care concepts addressing the needs of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population in an associate of science in nursing curriculum: Are faculty prepared? Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2015, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M.; Lundman, B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekoni, A.O.; Gale, N.K.; Manga-Atangana, B.; Bhadhuri, A.; Jolly, K. The effects of educational curricula and training on LGBT-specific health issues for healthcare students and professionals: A mixed-method systematic review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sherman, A.D.; Cimino, A.N.; Clark, K.D.; Smith, K.; Klepper, M.; Bower, K.M. LGBTQ+ health education for nurses: An innovative approach to improving nursing curricula. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 97, 104698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilicaslan, J.; Petrakis, M. Heteronormative models of health-care delivery: Investigating staff knowledge and confidence to meet the needs of LGBTIQ+ people. Soc. Work Health Care 2019, 58, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.L.; Nimmons, E.A.; Salcido, R., Jr.; Schnarrs, P.W. Multiplicity, Race, and Resilience: Transgender and Non-Binary People Building Community. Sociol. Inq. 2020, 90, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgel, H. Improving LGBT Cultural Competence in Nursing Students: An Integrative Review. ABNF J. 2017, 28, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal, K.; Bhatia, R.; Greene, G.J. Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadal, K.L. A decade of microaggression research and LGBTQ communities: An introduction to the special issue. J. Homosex. 2019, 66, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards Framework for Nursing and Midwifery Education; Nursing and Midwifery Council: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards-of-proficiency/standards-framework-for-nursing-and-midwifery-education/education-framework.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, E.; Wait, S.; Scrutton, J. The State of Play in Person-Centred Care: A Pragmatic Review of How Person-Centred Care is Defined, Applied and Measured; Health Foundation: London, UK, 2015; pp. 10–139. Available online: https://www.healthpolicypartnership.com/app/uploads/The-state-of-play-in-person-centred-care-summary.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E.; Carlsson, J.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Johansson, I.L.; Kjellgren, K.; et al. Person-centered care—ready for prime time. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Nursing. Fair Care for Trans and Non-Binary People: An RCN Guide for Nursing and Health Care Professionals, 3rd ed.; Royal College of Nursing: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/rcn-fair-care-trans-non-binary-uk-pub-009430 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Saunder, L. Online role play in mental health education. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2016, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

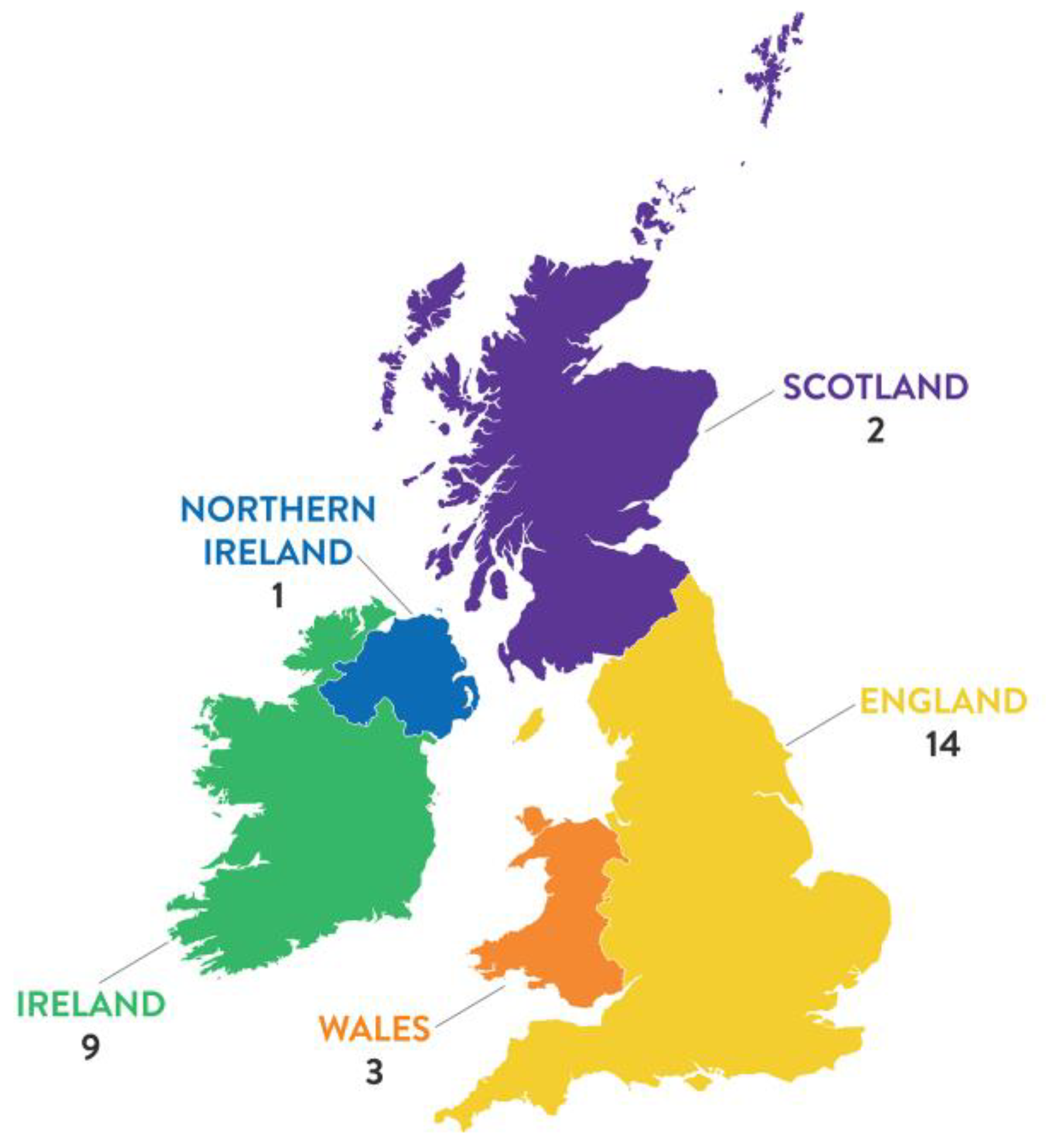

| Programme | Survey Responses | Interviews | Participant Pseudonym | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | 14 | 5 | Alex | Chris | Finn | Ryan | Taylor |

| Midwifery | 9 | 4 | Blake | Charlie | Jordon | Ray | |

| Nursing and midwifery | 6 | 3 | Joe | Lee | Sam | ||

| Total | 29 | 12 | |||||

| No | Potential Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Develop evidence-based LGBTQ+ educational guidelines to assist nurses and midwives to deliver modern contextualised LGBTQ+ care to service users. |

| 2 | Devise standalone module descriptors with an LGBTQ+ focus, which are designed to empower nurses and midwives to provide effective care to trans and non-binary service users and which include the points herein (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17) and also learning objectives cited in McCann et al. (2021) (Outline aims and objectives for lesson plans, and methods of teaching and assessing students’ skills in delivery). |

| 3 | Include a guide of relevant “non-binary” definitions, e.g., agender, androgyne, bigender, demigirl and demiboy, and provide contextual examples from nursing and midwifery practice. |

| 4 | Include a guide of “gender neutral” and “gender inclusive” language for nurses and midwives. |

| 5 | Provide examples of appropriate LGBTQ+ language to use when addressing and discussing care provision with service users. |

| 6 | Underpin LGBTQ+ education with an evidence-based Person-Centred Care (PCC) approach, which considers individual’s resources, interests, needs, and preferences, which includes: (1) care users’ narratives, (2) partnership in care, and (3) coherent documentation. |

| 7 | Ensure that all objectives are underpinned by an evidence base and use relevant research papers to underpin educational points made. |

| 8 | Involve members of the public in educational developments of LGBTQ+ education, ensuring that LGBTQ+ care users, staff, and students see themselves reflected in curriculum. |

| 9 | Develop sensitive scenarios and toolkits for rehearsal and role play within the classroom, on-line and/or clinical skills labs, which explore examples of where LGBTQ+ relevant communication can go well or astray. |

| 10 | Critically appraise the term microaggression and provide contextual examples of good and bad practice. |

| 11 | Discuss methods of documenting service users preferred terminology, pronouns, and language used to refer to parts of their body. |

| 12 | Outline legal requirements for confidentiality and avoiding disclosure of service user’s trans or non-binary status to unnecessary people. |

| 13 | Discuss social identity confusion which can occur when some LGBTQ+ people experience dissonance between their physical appearance and personal sense of being a man, woman, both, or neither and how gender identity is not necessarily fixed but fluid over time (emphasise importance of not making assumptions about people’s sexuality). |

| 14 | Outline methods of embedding LGBTQ+ teaching and learning across nursing and midwifery curriculum. |

| 15 | Plan systems to support students who have conflicting experiences, as they move from the classroom out into clinical practice. |

| 16 | Emphasise the importance of appointing a designated “LGBTQ+ champion” and outline their role and training required to effectively undertake this position. |

| 17 | Gain support from professional bodies to endorse teaching aids developed. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, M.; McCann, E.; Donohue, G.; Martin, C.H.; McCormick, F. LGBTQ+ Psychosocial Concerns in Nursing and Midwifery Education Programmes: Qualitative Findings from a Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111366

Brown M, McCann E, Donohue G, Martin CH, McCormick F. LGBTQ+ Psychosocial Concerns in Nursing and Midwifery Education Programmes: Qualitative Findings from a Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111366

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Michael, Edward McCann, Gráinne Donohue, Caroline Hollins Martin, and Freda McCormick. 2021. "LGBTQ+ Psychosocial Concerns in Nursing and Midwifery Education Programmes: Qualitative Findings from a Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111366