Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa

Abstract

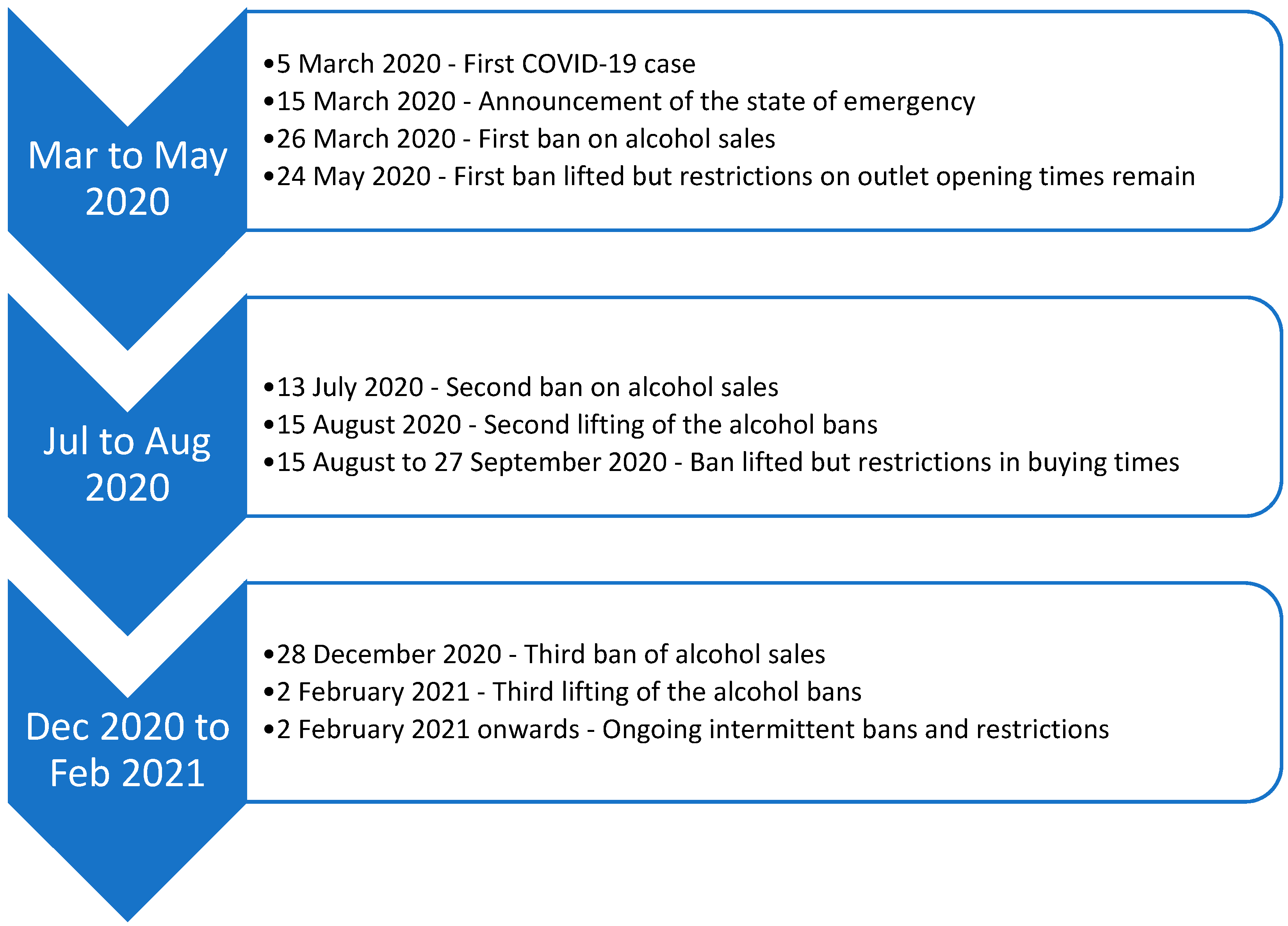

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Framework

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Government

3.2. The Alcohol Industry

3.3. Academics, Research Organisations and Public Health Advocates

3.4. Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs)

4. Discussion

4.1. Actors Involved and Strategies Employed

4.2. Political Context and Issue Framing

4.3. Use of Evidence and Policy Alternatives

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Probst, C.; Parry, C.D.H.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Rehm, J. The socioeconomic profile of alcohol-attributable mortality in South Africa: A modelling study. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Gmel, G.; Gmel, G.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Imtiaz, S.; Popova, S.; Probst, C.; Roerecke, M.; Room, R.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—An update. Addiction 2016, 112, 968–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, H.; Cook, S.; Matzopoulos, R.; London, L. Advancing alcohol research in low-income and middle-income countries: A global alcohol environment framework. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e001958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Norman, R.; Parry, C.; Bradshaw, D.; Plüddemann, A. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to alcohol use in South Africa in 2000. S. Afr. Med. J. 2007, 97, 664–672. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, A.A.; Dixon, J.; Lupez, K.; De Vries, S.; Wallis, L.A.; Ginde, A.; Mould-Millman, N.-K. The burden of trauma at a district hospital in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 9, S14–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casswell, S.; Thamarangsi, T. Reducing harm from alcohol: Call to action. Lancet 2009, 373, 2247–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, C.; London, L.; Myers, B. Delays in South Africa’s plans to ban alcohol advertising. Lancet 2014, 383, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, C.D.H. Alcohol policy in South Africa: A review of policy development processes between 1994 and 2009. Addiction 2010, 105, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhon, M.; Herrick, C. Alcohol control in the news: The politics of media representations of alcohol policy in South Africa. J. Health Politics Policy Law 2013, 38, 987–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Government. Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Disaster Management Act: Regulations to Address, Prevent and Combat the Spread of Coronavirus COVID-19: Amendment 2020. Pretoria. South Africa. Available online: www.gov.za (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Egbe, C.O.; Ngobese, S.P. COVID-19 lockdown and the tobacco product ban in South Africa. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzopoulos, R.; Walls, H.; Cook, S.; London, L. South Africa’s COVID-19 Alcohol Sales Ban: The Potential for Better Policy-Making. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 9, 486–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J.W.; Stano, E. Agendas, Alternatives Public Policies; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman, J.; Smith, S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: A framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet 2007, 370, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, S.; Williams, O.D. Frames, paradigms and power: Global health policy-making under neoliberalism. Glob. Soc. 2012, 26, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, D. Ideas, institutions policy change. J. Eur. Public Policy 2009, 16, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béland, D.; Cox, R.H. Ideas as coalition magnets: Coalition building, policy entrepreneurs power relations. J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 23, 428–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Ideas, politics public policy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, J. Ideas and actors in policy processes: Where is the interaction? Policy Stud. 2015, 36, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibiswa, N.K. Directed qualitative content analysis (DQlCA): A tool for conflict analysis. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 2059–2079. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan, D.H.; Wright, P.A. Media advocacy: Lessons from community experiences. J. Public Health Policy 1996, 17, 306–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howse, E.; Watts, C.; McGill, B.; Kite, J.; Rowbotham, S.; Hawe, P.; Bauman, A.; Freeman, B. Sydney’s ‘last drinks’ laws: A content analysis of news media coverage of views and arguments about a preventive health policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertscher, A.; London, L.; Orgill, M. Unpacking policy formulation and industry influence: The case of the draft control of marketing of alcoholic beverages bill in South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drahos, P. When the Weak Bargain with the Strong: Negotiations in the World Trade Organization. Int. Negot. 2003, 8, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.; Gostin, L.O. Big “Food, Tobacco Alcohol: Reducing Industry Influence on Noncommunicable Disease Prevention Laws and Policies: Comment on” Addressing NCDs: Challenges from Industry Market Promotion and Interferences. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savell, E.; Fooks, G.; Gilmore, A.B. How does the alcohol industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. Addiction 2016, 111, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.N. Crime, economy and governance in the new South Africa. Afr. Q. 1998, 38, 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, A.; Knowlton, L.M.; Schuurman, N.; Matzopoulos, R.; Zargaran, E.; Cinnamon, J.; Fawcett, V.; Taulu, T.; Hameed, S.M. Trauma Surveillance in Cape Town, South Africa: An Analysis of 9236 Consecutive Trauma Center Admissions. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebrits, K.; Du Plessis, S.; Jansen, A. The limits of laws: Traffic law enforcement in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pelser, E. How we really got it wrong: Understanding the failure of crime prevention. SA Crime Q. 2007, 2007, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akin-Onitolo, A.; Hawkins, B. Framing tobacco control: The case of the Nigerian tobacco tax debates. Health Policy Plan. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtle, J.; Langellier, B.; Lê-Scherban, F. A case study of the Philadelphia sugar-sweetened beverage tax policymaking process: Implications for policy development and advocacy. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2018, 24, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.J.; Baker, S. Responsible Citizens: Individuals, Health Policy under Neoliberalism; Anthem Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, S.; Schrecker, T. The double burden of neoliberalism? Noncommunicable disease policies and the global political economy of risk. Health Place 2016, 39, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.; Malbon, E.; Crammond, B.; Pescud, M.; Baker, P. Can the sociology of social problems help us to understand and manage ‘lifestyle drift’? Health Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godziewski, C. Is ‘Health in All Policies’ everybody’s responsibility? Discourses of multistakeholderism and the lifestyle drift phenomenon. Crit. Policy Stud. 2021, 15, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. “How do you measure up?” Assumptions about “obesity” and health-related behaviors and beliefs in two Australian “obesity” prevention campaigns. Fat Stud. 2014, 3, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosnitsyna, M.; Khorkina, N.; Sitdikov, M. Alcohol trade restrictions and alcohol consumption: On the effectiveness of state policy. Stud. Russ. Econ. Dev. 2017, 28, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnosaar, M. Time inconsistency and alcohol sales restrictions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 87, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, T.; Habicht, J. Decline in alcohol consumption in Estonia: Combined effects of strengthened alcohol policy and economic downturn. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011, 46, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navsaria, P.H.; Nicol, A.J.; Parry, C.D.H.; Matzopoulos, R.; Maqungo, S.; Gaudin, R. The effect of lockdown on intentional and non-intentional injury during the COVID-19 pandemic in Cape Town, South Africa: A preliminary report. S. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 111, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.M.; Marco, J.; Owolabi, E.O.; Duvenage, R.; Londani, M.; Lombard, C.; Parry, C.D.H. Trauma trends during COVID-19 alcohol prohibition at a South African regional hospital. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecher, E. A mountain or a molehill: Is the illicit trade in cigarettes undermining tobacco control policy in South Africa? Trends Organ. Crime 2010, 13, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowell, A.; Evans-Reeves, K.; Gilmore, A.B. Tobacco industry manipulation of data on and press coverage of the illicit tobacco trade in the UK. Tob. Control. 2014, 23, e35–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D. Places to Intervene in a System. Whole Earth 1997, 91, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe, J.; Shapiro, M.A.; Kim, H.K.; Bartolo, D.; Porticella, N. Narrative Persuasion, Causality, Complex Integration, and Support for Obesity Policy. Health Commun. 2013, 29, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngqangashe, Y.; Heenan, M.; Pescud, M. Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111494

Ngqangashe Y, Heenan M, Pescud M. Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111494

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgqangashe, Yandisa, Maddie Heenan, and Melanie Pescud. 2021. "Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111494

APA StyleNgqangashe, Y., Heenan, M., & Pescud, M. (2021). Regulating Alcohol: Strategies Used by Actors to Influence COVID-19 Related Alcohol Bans in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111494