Relationships between Child Development at School Entry and Adolescent Health—A Participatory Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Review Questions

- What are the associations between measures of child development recorded at school starting age (3–7 years) and subsequent health in adolescence (8–15 years)?

- What are the effect modifiers (socio-economic factors) of this relationship? (This will identify factors which alter the strength of the observed associations.)

- What are the mediators of this relationship? (This will identify factors or set of factors (pathways) which explain the observed associations.)

2.3. Definition of Terms

2.4. Study Design

Stakeholder Engagement to Design the Conceptual Diagram

2.5. Eligibility

2.6. Search Strategy

2.7. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.8. Quality Assessment

2.9. Data Synthesis

3. Results

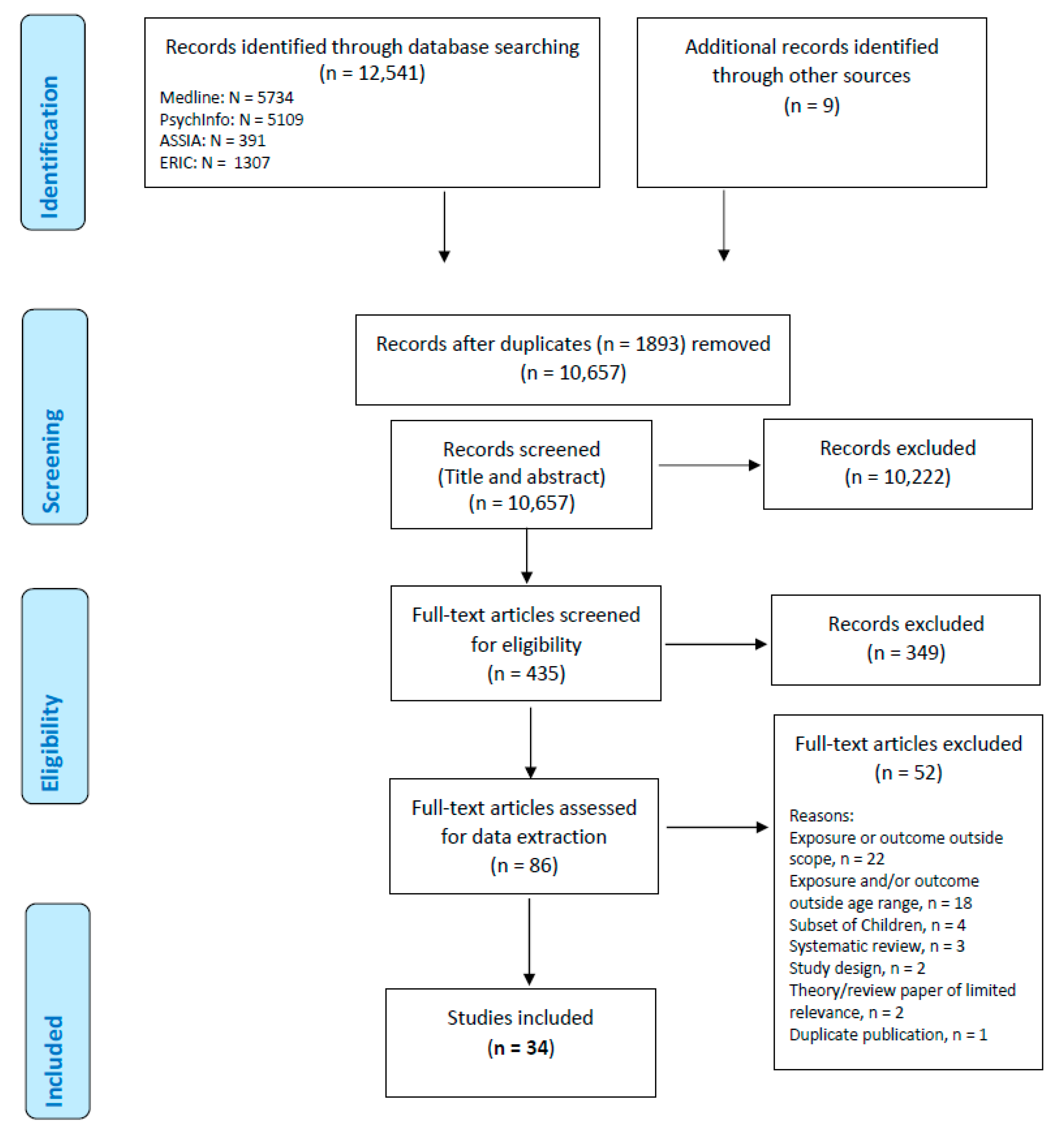

3.1. Literature Results

3.2. Study Design and Setting

3.3. Sample Size and Participant Characteristcs

3.4. Studies Identified across Different Domains of Child Development (Exposures) and Adolescent Outcomes

| Number of Studies by Exposure Domain | Outcome Measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | |||

| Domain: | Total studies | Mental Health | Weight | Academic |

| Socio-emotional | 24 * | 18 | 5 | 3 |

| Cognitive | 4 * | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Communication and Language | 2 | 2 | 1 ^ | - |

| Physical | 2 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Composite/All domains measured | 2 * | 2 | 1 | - |

| 34 | 26 | 9 | 4 | |

| Author (Citation) | Study Design | Country | Participants (% Females) | Exposure (Development Characteristic) and Age | Exposure Measurement Instrument | Outcome and Age | Outcome Measurement Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashford et al. [33] | Longitudinal | Holland | 294 (49.2) | Behaviour internalising and externalising—age 4 | Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL)—parent and teacher rated. | Internalising behaviours— age 11 | CBCL—parent and teacher report. |

| Berthelsen et al. [34] | Longitudinal | Australia | 4819 (49.1) | Child behaviour at age 4–5 and early ecological risk factors SEP, MMH, parenting anger, parenting warmth, parenting consistency | Child behaviour risk index measured as the sum of scores: sleep (emotional and dysregulation (both parent report) and inattention/ hyperactivity symptoms (mother rated). | Executive Function (age 14–15) | A composite score from three computerised tasks for assessing cognition (visual attention, visual working memory and spatial problem solving). |

| Bornstein et al. [35] | Longitudinal | US east coast | 118 (42.0) | Social competence at age 4 | Social competence as a construct, of: the peer acceptance subscale of the Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance Preschool Form, the Friendship Interview, and the socialization domain of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS). | Internalising and externalising behaviours at age 10 and 14 | At age 10 years—the CBCL and Teacher Report Form At age 14 years—the CBCL and Youth Self-Report |

| Bornstein et al. [36] | Longitudinal | US east coast | Two studies Study 2 extracted— 139 (39.6) | Language—communication skills—at age 4 | Two verbal subtests of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence—Revised and the VABS. | Internalising and externalising behaviours at age 10 and 14 | At age 10 years—the CBCL and Teacher Report Form At age 14 years—the CBCL and Youth Self-Report |

| Derks et al. [37] | Cohort | The Netherlands | One study of three extracted: Generation R study, 3794 (50.4) | Aggressive behaviour— at ages 5–7, 10 and 14 | CBCL—mother rated | BMI and body composition (fat mass and fat free mass)—at ages 6 and 10 | BMI—the Dutch national reference in the Growth Analyser program. FM and FFM—dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scanner |

| Duchesne et al. [38] | Longitudinal | Canada | 2000 (49.9) | Behaviour—hyperactivity, inattention, aggressiveness and prosociality—age 6Maternal warmth and maternal control also studied | Social Behaviour Questionnaire (SBQ)—teacher rated | Trajectory of anxiety at age 11–12 | Rated annually from kindergarten to Grade 6 using the Anxiety Scale from the SBQ—teacher report Children put into trajectory of anxiety |

| Fine et al. [39] | Longitudinal | US | 154 (50.0) | Emotional knowledge, internalising and externalising behaviours age 7 | Emotion knowledge— composite score from two tasks: (Emotional labelling & Emotion situation knowledge) Internalising and externalising behaviours—CBCL (teacher report) | Internalising behaviours age 11 | Child self-report aggregate of the following measures: Depression—Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Anxiety—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Loneliness. The Loneliness Scale Negative emotions—Differential emotions scale |

| Glaser et al. [40] | Longitudinal | UK | 5250 (50.7) | IQ age 8 | Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children | Depression symptoms—age 11, 13, 14 and 17 | Self-reported depressive symptoms were measured with the 13-item Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) Moderator: Pubertal stage at 11, 13 and 14 years was measured using a five-point rating scale |

| Gregory et al. [41] | Longitudinal | Australia | 3906 (49) | School readiness across 5 domains (physical, social, emotional, language and cognitive, communication and general knowledge)—age 5 | Australian version of the Early Development Instrument—teacher rated. Children scored as vulnerable, at risk or on-track | Age 11: four aspects of student wellbeing (life satisfaction, optimism, sadness and worries) | Middle Years Development Instrument—child self-report |

| Hay et al. [42] | Longitudinal | UK | 134 (53) | Co-operation (one form of prosocial behaviour) at age 4 | Tester’s rating of cooperativeness during the cognitive test (Tester’s Rating of Children’s Behaviour) and an observational measure of cooperation with the mother during the Etch-A-Sketch task | Internalising and externalising behaviour problems—at age 11 | SDQ and CAPA (Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment) |

| Hooper et al. [43] | Longitudinal | US | 74 (52.7) | Language—receptive and expressive language, receptive vocab and working memory—age 5 and 7–8 (kindergarten and second grade) | Receptive and expressive language -The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals. Receptive vocab (Peabody test) and Working memory (Competing Language Processing Task) | Behaviour problems— externalising problems (conduct and hyperactivity)—kindergarten, first, second, and third grade | Teachers completed assessments of the children’s behaviour using a standardized scale of behaviour—Conner’s’ Teacher Rating Scale-Revised |

| Howard et al. [44] | Cohort | Australia | 4983 (49) | Self-regulation—age 4–5 and 6–7 | Self-regulation problems were indexed by combining parent-, teacher-, and interviewer-report ratings of children’s self-regulatory behaviours | Academic and weight, mental health, substance use, crime, self-harm and suicidal ideation—age 15 | Academic achievement—children’s total scores on the Year 9 National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy Mental health problems were measured in a private face-to-face interview with the parent/carer who knew the adolescent best Overweight and obesity—BMI |

| Howes et al. [45] | Longitudinal | US | 307 (49.5) | Preschool social—emotional climate, Peer play, Behaviour problems, Teacher-child relationship quality—age 4 | Preschool social—emotional climate—average of children’s scores on measures in class. Peer play–peer play scale Behaviour problems—classroom behaviour inventory (CBI) Teacher-child relationship quality—The Pianta Student Teacher Relationship Scale | Social competence—Behaviour with peers at age 8 | Teacher reports using the Cassidy and Asher Teacher Assessment of Social behaviour Questionnaire |

| Jaspers et al. [65] | Longitudinal (retrospective) | Holland | 2139 (50.9) | Behavioural features at age 4—”sleeping, eating, and enuresis problems” and “emotional and behaviour problems” | Assessed by Preventative Child Healthcare professionals. | Behavioural and emotional problems at age 10 to 12 | CBCL—parent completed |

| Lecompte et al. [46] | Longitudinal | Canada | 68 (48.5) | Emotional wellbeing—Child-parent attachment at age 3–4 | Lab based separation reunion procedure | Anxiety and depressive symptoms and self-esteem (age 11–12) | Dominic Interactive Questionnaire- computerised self-report measure of common mental health disorders in childhood. Self-esteem–self-perception profile for children—self-report |

| Lee et al. [47] | Longitudinal | US | 762 (46.3) | Behaviour internalising and externalising— age 5 | CBCL—primary caregiver completed | Behaviour internalising and externalising—age 9 | CBCL—primary caregiver completed |

| Louise at al. [48] | Longitudinal | Western Australia | 2900 (not stated) | Behaviour— aggressive—age 5, 8, 10 and 14 | CBCL, youth self-report at age 14 and teacher report at age 10 and 14 | Weight at age 5, 8,10 and 14 | Weight—Wedderburn digital chair scale Height was measured using a Holtain Stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m2) |

| McKenzie et al. [49] | Longitudinal | USA | 207 (49.7) | Fundamental movement skills—Balance, agility, eye-hand coordination—age 4,5 and 6 | Movement skill tests in the child’s home | Physical Activity—age 12 | Trained assessors administered the 7-day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) in the child’s home on two occasions, approximately 6 months apart |

| Meagher et al. [50] | Longitudinal | USA | 56 (55.4) | Socio-emotional behaviours observed in pre-school—age 4 | Externalising and internalising symptoms from the CBCL—teacher report Observed negative effect by research assistants | Depression symptoms— age 8 | Child depression inventory—self-report |

| Nelson et al. [51] | Longitudinal | US | 280 (47.9) | Executive control and Foundational Cognitive Abilities at age 5 | EC–9-tasks administered to each child during individual sessions in the laboratory (working memory, inhibitory control, and flexible shifting) FCA—via the Woodcock-Johnson-III Brief Intellectual Assessment | Depression and Anxiety symptoms— Age 9–10. | Child Depression Inventory—child self-report Anxiety symptoms—Revised Child Manifest Anxiety Scale—child self-report Externalising symptoms—parents completed the ODD and ADHD-Hyperactivity subscales of the Conners 3rd Edition Parent Ratings Scale |

| Pedersen et al. [53] | Longitudinal | Canada | 551 (45.4) | Behaviour—anxiety/ social withdrawal and disruptive behaviour—age 6 | Social Behaviour Questionnaire (SBQ)—mother and teacher rated | Peer rejection & Friendedness (at age 8 to 11) Depressive symptoms Loneliness Delinquency—at age 13 | Peer rejection–peer nominations. Friendedness—Children were also asked to nominate up to four best friends Depressive symptoms—CDI—child report Loneliness-self-report measure developed by Asher et al. 1984 Delinquency—Self-Reported Delinquency Questionnaire (SRDQ) |

| Piche et al. [54] | Longitudinal | Canada | 966 (47.0) | Self-regulatory skills: classroom engagement and behavioural regulation (emotional distress, physical aggression, impulsivity)—age 6 | Classroom engagement (teacher rated) and Behavioural regulation using the SBQ (teacher rated) | Child Sports Participation and BMI— Age 10 | Parents reported on their child’s weekly involvement in structured sports outside of school during the past school year BMI was derived from direct height and weight measures made by trained, independent examiners |

| Piche et al. [55] | Longitudinal | Canada | 1516 (51.9) | Participation in structured and unstructured physical activity—age 7 | Parents reported on their children’s participation in structured and unstructured physical activity | Age 8 Depressive symptoms | Depression symptoms assessed through the Social Behaviour Questionnaire |

| Rudasill et al. [56] | Longitudinal | USA | 1156 (48.8) | Child temperament (negative emotionality at age 4½ and emotional reactivity at age 7–12) (Student-teacher relationship -teacher perception and child perception tested as mediators) | Negative emotionality: Mothers completed eight subscales from the Children’s Behaviour Questionnaire Emotional reactivity: Children’s emotional responses to events and environmental stimuli were rated by mothers using a measure designed for use in the NICHD SECCYD | Depressive symptoms in sixth grade (age 11–12) | Mother report of their children’s depressive symptoms was measured in 6th grade with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders oriented Affective Problems subscale of the Child Behaviour Checklist |

| Rudolph et al. [57] | Longitudinal | USA | 433 (55.0) | Peer Victimization (static and dynamic) (Age 7–12, 2nd to 5th grade) | Children and teachers completed a revised version of the Social Experiences Questionnaire to assess children’s exposure to peer victimization. | Depression symptoms and Aggressive behaviour—Age 11–12 (5th grade) | Depression symptoms—Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Child report) Aggressive behaviour—Children’s Social Behaviour Scale (teacher report) |

| Sandstrom et al. [66] | Meta-analysis | Any | 8836 (51.5) | The mean age at the first BI assessment was 3.61 years | BI: defined as shyness, fear, and avoidance when faced with new stimuli | The mean age at the anxiety assessment was 10.39 years | Anxiety and specific anxiety types searched |

| Sasser et al. [58] | Longitudinal | USA | 356 (54.0) | Intervention targeting social-emotional functioning and language-emergent literacy skills in the first year of pre-school. Executive function measured before and after preschool and each year to third grade (age 8) | Executive function assessment by trained examiners. Children assigned to either low, moderate or high executive function trajectory | Third grade academic outcomes | Reading fluency, language-arts and mathematics (all teacher rated), children self-evaluation of reading ability |

| Shapero et al. [59] | Longitudinal | USA | 958 (48.0) | Emotional—emotional reactivity at age 8. (Household income and household chaos also studied.Household Chaosand Household income also studied.) | Emotional reactivity—mother report—10-item questionnaire about their perceptions of how their child expresses emotions in response to events | Emotional and behavioural problems— age 15 | Adolescent Emotional and BehaviouralProblems—Youth Self-Report. |

| Slemming et al. [60] | Longitudinal | Denmark | 1336 (49.0) | Behaviour: anxious–fearful, hyperactive–distractible, and hostile– aggressive—age 3–4 | Preschool behaviour questionnaire (PBQ)—parent report | Internalising problems— age 10–12 | Emotional difficulties were measured at age 10–12 years with the parent-administered strength and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) |

| Straatmannet al. [61] | Longitudinal | UK | 10262 (not stated) | Five central domains of a health check in England: (1) personal, social and emotional development, (2) communication and language, (3) physical health, (4) learning and cognitive development and (5) physical development and self-care)—at age 3 | Health visitor assessment at routine health check | Language, weight, socioemotional behaviour— age 11 | Language—British Ability Scale Second Edition (BAS II) Verbal Similarities test Weight was derived from the body mass index (BMI), using the age and sex- International Obesity Task Force cut-offs Socio-emotional behaviour—SDQ—mother report |

| Sutin et al. [62] | Longitudinal | Australia | 4153 (71.6) | Temperament— sociability, persistence, negative reactivity. Age 4–5 | Parents completed a 12-item measure of temperament based on the Childhood Temperament Questionnaire | Weight and weight attitudes and behaviour—age 14–15 | Weight—BMI and waist circumference at all ages Weight attitudes and behaviour. At ages 14–15 years, study children self-reported on several aspects of their attitudes and behaviours. |

| Weeks et al. [63] | Longitudinal | Canada | 4405 (50.0) | Verbal ability (age 4–5) and Math skills— age 7–11 | Verbal Ability: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R) Math skills—Mathematics Computation Test (MCT) | Internalising symptoms of anxiety and depression—age 12–13 and 14–15 | Questionnaire that included 7 items from the Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS-R), assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression—self-report. |

| Yan et al. [64] | Longitudinal | USA | 695 (49.1) | Emotional Wellbeing—child parent relationship—Age 6 | Both fathers and mothers rated their relationships (conflict and closeness) with the child at Grade 1, 3, 4 and 5—Child-Parent Relationship Scale | Loneliness at grades 1, 3 and 5 (age 10–11) | Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire—child self-report |

3.5. Quality Assessment

3.6. Narrative Synthesis

- “Mental health related symptoms”—this incorporated: internalising symptoms (general, depression, anxiety, loneliness and self-esteem), externalising (general and ‘delinquency’), socio-emotional behaviour problems, social competence, wellbeing, self-harm and suicidal ideation.

- “Weight, diet and physical activity”—this incorporated: BMI, overweight/obese, sports participation, unhealthy weight attitudes, and healthy dietary habits.

- For secondary outcomes, the group included executive function and outcomes from academic tests.

- Domain: Social and emotional development. This was further subdivided to aid analysis, as follows:

- ○

- Internalising—internally focused behaviour such as inhibition and withdrawal.

- ○

- Externalising—externally focused behaviour such as aggression, attention problems, hyperactivity and “delinquent” behaviour.

- ○

- Emotional—internal factors such as social competence, emotion knowledge, pro-social, co-operative and self-regulation skills. External factors such as peer relations, parent-child relationships, teacher-child relationships, socio-emotional climate of school/pre-school setting.

- ○

- Temperament—negative emotionality, emotional reactivity and persistence.

- Domain: Language and communication. This comprised the ability to listen, understand and speak. Exposures included: receptive and expressive vocabulary. Receptive relates to understanding of words and expressive relates to the ability to use words for expression.

- Domain: Cognitive development. This comprised mathematics skills, executive control, foundational cognitive ability, verbal ability/literacy and Intelligence Quotient (IQ)

- Domain: Physical development. This involved fundamental movement skills (balance, agility, hand-eye co-ordination) and participation in structured and unstructured physical activity

- Multiple domains.

3.7. Primary Outcomes

3.7.1. Mental Health

Summary of Associations between Child Development and Mental Health

Summary of Associations between Socio-Emotional Development and Mental Health

Exposure of Internalising Behaviours at School Entry and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposure of Externalising Behaviours at School Entry and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposures of Emotional Wellbeing at School Entry and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposures of Temperament at School Entry and Subsequent Mental Health

Summary of Associations between Language and Communication, Cognitive Development, Physical Development, and Multiple Domains and Mental Health

Exposures within the Language and Communication Domain and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposures within the Cognitive Domain and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposures within Physical Development Domain and Subsequent Mental Health

Exposures Incorporating Multiple Domains and Subsequent Mental Health

3.7.2. Weight, Diet and Physical Activity Outcomes

Summary of Associations between Child Development and Weight

Summary of Associations between Socio-Emotional Development and Weight

Exposures of Externalising, Emotional Wellbeing and Temperament and Subsequent Weight

Summary of Associations between Domains of: Language and Communication, Cognitive, Physical Development, Multiple Domains and Weight

3.8. Secondary Outcomes

3.8.1. Academic Tests and Executive Function

Summary of Associations between Child Development and Academic Outcomes

Exposures within the Socio-Emotional and Cognition Domains and Subsequent Academic Outcomes

3.9. Factors Affecting Relationships

3.9.1. Mediators

3.9.2. Moderators

3.9.3. Factors Pertaining to the Family Stress Pathway—Moderating Associations between Child Development and Mental Health

3.9.4. Factors Pertaining to the Knowledge/Literacy Pathway—Moderating and Mediating Associations between Child Development and Academic Outcomes

3.9.5. Factors Pertaining to the Social/Cognitive Pathway—Mediating Associations between Child Development and Mental Health

3.9.6. Factors Pertaining to Child Characteristics—Moderating Associations between Child Development and Weight and Mental Health

3.10. Conceptual Model/Diagram Development

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. State of Child. Health 2020; RCPCH London, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. Fair Society, Healthier Lives: The Marmot Review. 2010. Available online: https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report-pdf.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Centre on the Developing Child. The Foundations of Lifelong Health Are Built in Early Childhood. 2010. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-foundations-of-lifelong-health-are-built-in-early-childhood/ (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Fox, S.E.; Levitt, P.; Nelson, C.A. How the Timing and Quality of Early Experiences Influence the Development of Brain Architecture. Child. Dev. 2010, 81, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children. Science 2006, 312, 1900–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, J.C.; Bamidis, P.D.; Burberry, J.; Rudolf, M.C.J. The First Thousand Days: Early, integrated and evidence-based approaches to improving child health: Coming to a population near you? Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.; Barnes, A.; Baxter, S.; Beynon, C.; Clowes, M.; Dallat, M.; Davies, A.R.; Furber, A.; Goyder, E.; Jeffery, C.; et al. Learning across the UK: A review of public health systems and policy approaches to early child development since political devolution. J. Public Health 2019, 42, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.J.; Proulx, K.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Matthews, S.G.; Vaivada, T.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Rao, N.; Ip, P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; et al. Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Trang, K.T.; Love, H.R.; Templin, J. School Readiness Profiles and Growth in Academic Achievement. Front. Educ. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabol, T.J.; Pianta, R.C. Patterns of school readiness forecast achievement and socioemotional development at the end of elementary school. Child. Dev. 2012, 83, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithers, L.G.; Sawyer Alyssa, C.P.; Chittleborough, C.R.; Davies, N.M.; Davey Smith, G.; Lynch, J.W. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of early life non-cognitive skills on academic, psychosocial, cognitive and health outcomes. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onise, K.; Lynch, J.W.; Sawyer, M.G.; McDermott, R.A. Can preschool improve child health outcomes? A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, S.; Conti, G.; Farquharson, C.; Ginja, R. The Health Effects of Sure Start. London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PACEY. What Does “School Ready” Really Mean?—A Research Report from Professional Association for Childcare and Early Years; Professional Association for Childcare and Early Years: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage Setting the Standards for Learning, Development and Care for Children from Birth to Five; London, UK, 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-years-foundation-stage-framework--2 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. School Readiness: A Conceptual Framework; New York, NY, USA, 2012. Available online: https://sites.unicef.org/earlychildhood/files/Child2Child_ConceptualFramework_FINAL(1).pdf (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Bradbury, A.; Roberts-Holmes, G. The Datafication of Primary and Early Years Education: Playing with Numbers; Routlege: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zajacova, A.; Lawrence, E.M. The relationship between education and health: Reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; von Hippel, P. An Education Gradient in Health, a Health Gradient in Education, or a Confounded Gradient in Both? Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.; Barnes, A.; Strong, M.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Impact of child development at primary school entry on adolescent health—protocol for a participatory systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The, P.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, A.; Dundas, R.; Whitehead, M.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Pathways to inequalities in child health. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés Pascual, A.; Moyano Muñoz, N.; Quílez Robres, A. The Relationship Between Executive Functions and Academic Performance in Primary Education: Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, B.A. Basic Concept Scale Revised; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, D. Introduction to Systematic Reviews (Lecture); University of Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendoorn, W.E.; van Poppel, M.N.; Bongers, P.M.; Koes, B.W.; Bouter, L.M. Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1999, 25, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- te Velde, S.J.; van Nassau, F.; Uijtdewilligen, L.; van Stralen, M.M.; Cardon, G.; De Craemer, M.; Manios, Y.; Brug, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.; ToyBox-Study Group. Energy balance-related behaviours associated with overweight and obesity in preschool children: A systematic review of prospective studies. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13 (Suppl. S1), 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; McAleenan, A.; Reeves, B.C.; Higgins, J.P.T. Chapter 25: Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2; Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V., Eds.; 2021; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-25 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Baxter, S.K.; Blank, L.; Woods, H.B.; Payne, N.; Rimmer, M.; Goyder, E. Using logic model methods in systematic review synthesis: Describing complex pathways in referral management interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.; Johnson, M.; Chambers, D.; Sutton, A.; Goyder, E.; Booth, A. The effects of integrated care: A systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, J.; Smit, F.; van Lier, P.A.; Cuijpers, P.; Koot, H.M. Early risk indicators of internalizing problems in late childhood: A 9-year longitudinal study. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthelsen, D.; Hayes, N.; White, S.L.J.; Williams, K.E. Executive Function in Adolescence: Associations with Child and Family Risk Factors and Self-Regulation in Early Childhood. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Hahn, C.-S.; Haynes, O. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Hahn, C.-S.; Suwalsky, J.T. Language and internalizing and externalizing behavioral adjustment: Developmental pathways from childhood to adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2013, 25, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, I.P.M.; Bolhuis, K.; Yalcin, Z.; Gaillard, R.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Larsson, H.; Lundstrom, S.; Lichtenstein, P.; van Beijsterveldt, C.E.M.; Bartels, M.; et al. Testing Bidirectional Associations Between Childhood Aggression and BMI: Results from Three Cohorts. Obesity 2019, 27, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Larose, S.; Vitaro, F.; Tremblay, R.E. Trajectories of anxiety in a population sample of children: Clarifying the role of children’s behavioral characteristics and maternal parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, S.E.; Izard, C.E.; Mostow, A.J.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Ackerman, B.P. First grade emotion knowledge as a predictor of fifth grade self-reported internalizing behaviors in children from economically disadvantaged families. Dev. Psychopathol. 2003, 15, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Gunnell, D.; Timpson, N.J.; Joinson, C.; Zammit, S.; Smith, G.D.; Lewis, G. Age- and puberty-dependent association between IQ score in early childhood and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, T.; Dal Grande, E.; Brushe, M.; Engelhardt, D.; Luddy, S.; Guhn, M.; Gadermann, A.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Brinkman, S. Associations between School Readiness and Student Wellbeing: A Six-Year Follow Up Study. Child. Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, D.F.; Pawlby, S. Prosocial development in relation to children’s and mothers’ psychological problems. Child. Dev. 2003, 74, 1314–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, S.R.; Roberts, J.E.; Zeisel, S.A.; Poe, M. Core Language Predictors of Behavioral Functioning in Early Elementary School Children: Concurrent and Longitudinal Findings. Behav. Disord. 2003, 29, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, S.J.; Williams, K.E. Early Self-Regulation, Early Self-Regulatory Change, and Their Longitudinal Relations to Adolescents′ Academic, Health, and Mental Well-Being Outcomes. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics 2018, 39, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C. Social-emotional classroom climate in child care, child-teacher relationships and children’s second grade peer relations. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecompte, V.; Moss, E.; Cyr, C.; Pascuzzo, K. Preschool attachment, self-esteem and the development of preadolescent anxiety and depressive symptoms. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2014, 16, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-k.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J. Resident fathers’ positive engagement, family poverty, and change in child behavior problems. Fam. Relat. Interdiscip. J. Appl. Fam. Stud. 2017, 66, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louise, S.; Warrington, N.; McCaskie, P.; Oddy, W.; Zubrick, S.; Hands, B.; Mori, T.; Briollais, L.; Silburn, S.; Palmer, L.; et al. Associations between aggressive behaviour scores and cardiovascular risk factors in childhood. Pediatric Obes. 2012, 7, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Broyles, S.L.; Zive, M.M.; Nader, P.R.; Berry, C.C.; Brennan, J.J. Childhood movement skills: Predictors of physical activity in Anglo American and Mexican American adolescents? Res. Q Exerc. Sport 2002, 73, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, S.M.; Arnold, D.H.; Doctoroff, G.L.; Dobbs, J.; Fisher, P.H. Social-Emotional Problems in Early Childhood and the Development of Depressive Symptoms in School-Age Children. Early Educ. Dev. 2009, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.D.; Kidwell, K.M.; Nelson, J.M.; Tomaso, C.C.; Hankey, M.; Espy, K.A. Preschool executive control and internalizing symptoms in elementary school. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2018, 46, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.S.; Caroline, F. Children’s School Readiness: Implications for Eliminating Future Disparities in Health and Education. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.; Vitaro, F.; Barker, E.D.; Borge, A.I. The Timing of Middle-Childhood Peer Rejection and Friendship: Linking Early Behavior to Early-Adolescent Adjustment. Child. Dev. 2007, 78, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, G.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Pagani, L.S. Kindergarten Self-Regulation as a Predictor of Body Mass Index and Sports Participation in Fourth Grade Students. Mind Brain Educ. 2012, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, G.; Huỳnh, C.; Villatte, A. Physical activity and child depressive symptoms: Findings from the QLSCD. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2019, 51, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Pössel, P.; Winkeljohn, B.S.; Niehaus, K. Stephanie Winkeljohn; Niehaus, Kate. Teacher support mediates concurrent and longitudinal associations between temperament and mild depressive symptoms in sixth grade. Early Child. Dev. Care 2014, 184, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rudolph, K.D.; Troop-Gordon, W.; Hessel, E.T.; Schmidt, J.D. A Latent Growth Curve Analysis of Early and Increasing Peer Victimization as Predictors of Mental Health across Elementary School. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2011, 40, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasser, T.R.; Bierman, K.L.; Heinrichs, B.; Nix, R.L. Preschool Intervention Can Promote Sustained Growth in the Executive-Function Skills of Children Exhibiting Early Deficits. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapero, B.G.; Steinberg, L. Emotional reactivity and exposure to household stress in childhood predict psychological problems in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemming, K.; Sørensen, M.J.; Thomsen, P.H.; Obel, C.; Henriksen, T.B.; Linnet, K.M. The association between preschool behavioural problems and internalizing difficulties at age 10-12 years. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 19, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straatmann, V.S.; Pearce, A.; Hope, S.; Barr, B.; Whitehead, M.; Law, C.; Taylor-Robinson, D. How well can poor child health and development be predicted by data collected in early childhood? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutin, A.R.; A Kerr, J.; Terracciano, A. Temperament and body weight from ages 4 to 15 years. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weeks, M.; Wild, T.; Ploubidis, G.; Naicker, K.; Cairney, J.; North, C.; Colman, I. Childhood cognitive ability and its relationship with anxiety and depression in adolescence. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 152–154, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Feng, X.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J. Longitudinal associations between parent-child relationships in middle childhood and child-perceived loneliness. J. Fam. Psychol. 2018, 32, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, M.; De Winter, A.F.; De Meer, G.; Stewart, R.E.; Verhulst, F.C.; Ormel, J.; Reijneveld, S.A. Early findings of preventive child healthcare professionals predict psychosocial problems in preadolescence: The TRAILS study. J. Pediatrics 2010, 157, 316–321.e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sandstrom, A.; Uher, R.; Pavlova, B. Prospective Association between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2020, 48, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. IS 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication; Donsbach, W., Ed.; Blackwells: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, K.C.; Richardson, C.G.; Gadermann, A.M.; Emerson, S.D.; Shoveller, J.; Guhn, M. Association of Childhood Social-Emotional Functioning Profiles at School Entry With Early-Onset Mental Health Conditions. JAMA Netw. 2019, 2, e186694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, İ.B.; Lucassen, N.; van Lier, P.A.C.; de Haan, A.D.; Prinzie, P. Early childhood internalizing problems, externalizing problems and their co-occurrence and (mal)adaptive functioning in emerging adulthood: A 16-year follow-up study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, C.J.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.M.; Bray, B.C. The dynamics of internalizing and externalizing comorbidity across the early school years. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28, 1033–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringaris, A.; Lewis, G.; Maughan, B. Developmental pathways from childhood conduct problems to early adult depression: Findings from the ALSPAC cohort. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbel, R.; Mason, T.B.; Dunton, G.F. Transactional links between children daily emotions and internalizing symptoms: A six-wave ecological momentary assessment study. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 06, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T.L.; Eggum, N.D. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalay, P.; Hardman, C.A. Comorbidity, Codevelopment, and Temporal Associations Between Body Mass Index and Internalizing Symptoms From Early Childhood to Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.; Scalzi, D.; Lynch, J.; Smithers, L.G. Do thin, overweight and obese children have poorer development than their healthy-weight peers at the start of school? Findings from a South Australian data linkage study. Early Child. Res. Q. 2016, 35, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.L.; Cunningham, S.A. Social Competence and Obesity in Elementary School. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.L.; Christensen, D.; Jose, K.; Zubrick, S.R. Universal child health and early education service use from birth through Kindergarten and developmental vulnerability in the Preparatory Year (age 5 years) in Tasmania, Australia. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 00, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.L.; McMinn, D.; Daly, M. A Bidirectional Relationship between Executive Function and Health Behavior: Evidence, Implications, and Future Directions. Front. Neurosci 2016, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattan, S.; Conti, G.; Farquharson, C.; Ginja, G.; Pecher, M. The Health Impacts of Sure Start; The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2021. Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/14139 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Bundy, D.A.P.; de Silva, N.; Horton, S.; Patton, G.C.; Schultz, L.; Jamison, D.T. Child and Adolescent Health and Development: Realizing Neglected Potential. In Child and Adolescent Health and Development, 3rd ed.; Bundy, D.A.P., de Silva, N., Horton, S., Jamison, D.T., Patton, G.C., Eds.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Viner, R.M.; Allen, N.B.; Patton, G.C. Puberty, Developmental Processes and Health Interventions. In Child and Adolescent Health and Development, 3rd ed.; Bundy, D.A.P., de Silva, N., Horton, S., Jamison, D.T., Patton, G.C., Eds.; World Bank: Washinton, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.A.; Truman, B.I. Education Improves Public Health and Promotes Health Equity. Int. J. Health Serv. 2015, 45, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, N.J.; Joseph, G.; Pasick, R.J.; Barker, J.C. Theorizing social context: Rethinking behavioral theory. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 36, 55s–70s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAteer, J.; Di Ruggiero, E.; Fraser, A.; Frank, J.W. Bridging the academic and practice/policy gap in public health: Perspectives from Scotland and Canada. J. Public Health 2018, 41, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population and context | Studies must include children, some or all of whom are aged between 3 and 15 years, across socio-economic strata in high-income country settings, defined as OECD membership. | Studies of children from non-OECD countries. Studies which focus solely on a particular subset of children with a particular health or development need. |

| Exposure | A measure of child development at school starting age (3–7 years), defined as: cognitive or physical or linguistic or socio-emotional development at school starting age, measured by any of the following:

Studies that explore mechanisms or pathways between child development at school starting age and these outcomes. | Studies reporting neither data nor mechanism between exposure and outcome will be excluded. |

| Outcome | Primary Outcome(s) The review will incorporate evidence health and wellbeing outcomes, reported between the ages of 8 and 15 years, specifically:

| Studies reporting neither data nor mechanism between exposure and outcome will be excluded. |

| Study design and sources | Observational studies (ecological, case-control, cohort (prospective and retrospective)) RCTs, Quasi-experimental, Review level studies including theory papers. | Cross-sectional studies, conference abstracts, books, dissertations, or opinion pieces. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Black, M.; Barnes, A.; Strong, M.; Brook, A.; Ray, A.; Holden, B.; Foster, C.; Taylor-Robinson, D. Relationships between Child Development at School Entry and Adolescent Health—A Participatory Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111613

Black M, Barnes A, Strong M, Brook A, Ray A, Holden B, Foster C, Taylor-Robinson D. Relationships between Child Development at School Entry and Adolescent Health—A Participatory Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111613

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlack, Michelle, Amy Barnes, Mark Strong, Anna Brook, Anna Ray, Ben Holden, Clare Foster, and David Taylor-Robinson. 2021. "Relationships between Child Development at School Entry and Adolescent Health—A Participatory Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111613

APA StyleBlack, M., Barnes, A., Strong, M., Brook, A., Ray, A., Holden, B., Foster, C., & Taylor-Robinson, D. (2021). Relationships between Child Development at School Entry and Adolescent Health—A Participatory Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11613. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111613