Aspirations and Worries: The Role of Parental Intrinsic Motivation in Establishing Oral Health Practices for Indigenous Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

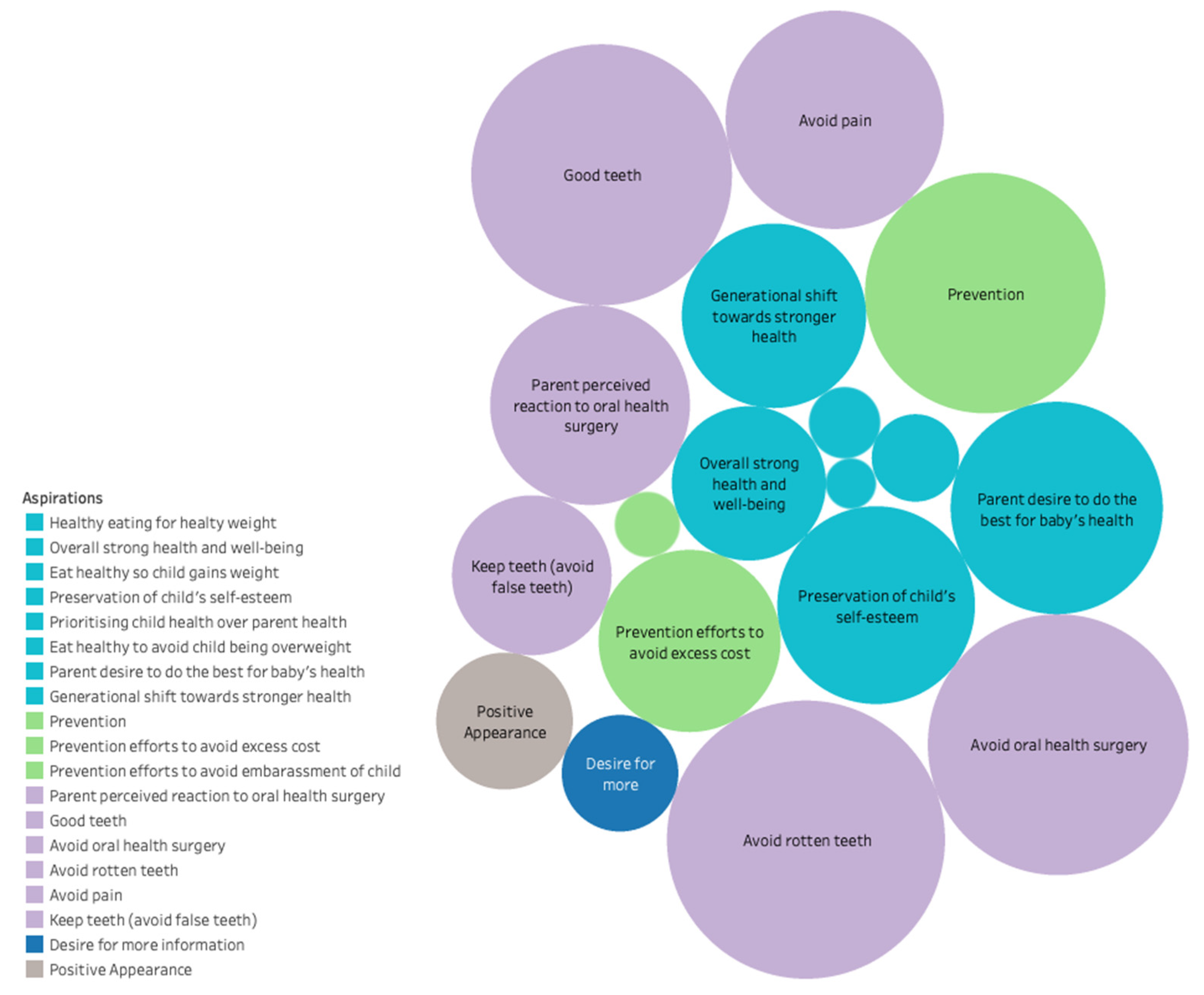

3.1. Aspirations

“I’m very proud, they’ve got very good education, like, you know, they speak really well… I live for my kids and their education and health is my number one priority, I don’t give a crap about anyone else’s but these two are my driven force.”

“[If my kids have no fillings, they’ll] feel very pretty about themselves … pretty inside and outside and that’s something that every girl needs to feel. They need to feel secure about themselves and everything and if there’s a lot of Aboriginal girls out there with missing teeth, they don’t like it… not one little bit they don’t like it and not even the boys like it. Because we are very emotional people when it comes to our bodies and our hearts and our souls and everything you know, Aboriginals do care, in the end they do care, they might not show it but they do, yes.”

3.2. Worries

“I don’t really know what a lot of foods have in them as such. That’s why I kind of worry about a lot, because I know a lot of the foods that he eats, he really shouldn’t eat. Like, a lot of them I’ve cut down on. Like he hardly ever eats chocolate any more except for the chocolate milk... So I’m trying to keep as healthy as I can [with] beans, peas, corn and zucchinis and pumpkin, and he eats it all.”

“This is one thing that I worry about, that she’s going to have bad teeth because I’ve got bad teeth that run[s] in my family … When we went for a hospital appointment [we were told] one of the leading diseases is gum disease, for Aboriginal people, so I get really funny because that’s something that I was funny about growing up, was having bad teeth. So, yes, just to make sure that everything was okay, we decided we would take her [to the dentist] just to check that, yes, she’s where she’s supposed to be.”

“I just think overall, like personal appearance, you know, when they get older… I think part of me is my teeth. And if you have rotten teeth, you’re not really confident. You know what I mean? Like you don’t want to smile. You got stinky breath. You don’t want to breathe on people. You can’t eat certain things because your tooth breaks and falls out or, you know, all sorts of reasons, especially oral health.”

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watt, R.G.; Petersen, P.E. Periodontal health through public health—The case for oral health promotion. Periodontology 2000 2012, 60, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, N.P.T.; Chu, C.H.; Fontana, M.; Lo, E.C.M.; Thomson, W.M.; Uribe, S.; Heiland, M.; Jepsen, S.; Schwendicke, F. A Century of Change towards Prevention and Minimal Intervention in Cariology. J. Dent. Res. 2019, 98, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, G.V. A Work on Operative Dentistry; Medico-Dental Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, R.G. From victim blaming to upstream action: Tackling the social determinants of oral health inequalities. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejerskov, O. Changing Paradigms in Concepts on Dental Caries: Consequences for Oral Health Care. Caries Res. 2004, 38, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.E.; Hale, K.J. The paradigm shift in the etiology, prevention, and management of dental caries: Its effect on the practice of clinical dentistry. J. Calif. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 31, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cartes-Velasquez, R.; Araya, C.; Flores, R.; Luengo, L.; Castillo, F.; Bustos, A. A motivational interview intervention delivered at home to improve the oral health literacy and reduce the morbidity of Chilean disadvantaged families: A study protocol for a community trial. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e011819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Mason, P.; Butler, C. Health Behavior Change: A Guide for Practitioners; Churchill Livingstone: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperman, N.A.; Arnsten, J.H. Motivational interviewing for improving adherence to antiretroviral medications. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2005, 2, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Owens, S.A.; Gansky, S.A.; Platt, L.J.; Weintraub, J.A.; Soobader, M.-J.; Bramlett, M.D.; Newacheck, P.W. Influences on Children’s Oral Health: A Conceptual Model. Pediatrics 2007, 120, e510–e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plutzer, K.; Spencer, A.J. Efficacy of an oral health promotion intervention in the prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2008, 36, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollister, M.C.; Anema, M.G. Health Behavior Models and Oral Health: A Review. J. Dent. Hyg. 2004, 78, 6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arrow, P.; Raheb, J.; Miller, M. Brief oral health promotion intervention among parents of young children to reduce early childhood dental decay. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ismail, A.I.; Ondersma, S.; Willem Jedele, J.M.; Little, R.J.; Lepkowski, J.M. Evaluation of a brief tailored motivational intervention to prevent early childhood caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2011, 39, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R.L.; Veronneau, J.; Leroux, B. Effectiveness of Maternal Counseling in Reducing Caries in Cree Children. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 1032–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvara, B.C.; Faustino-Silva, D.D.; Meyer, E.; Hugo, F.N.; Hilgert, J.B.; Celeste, R.K. Motivational Interviewing in Preventing Early Childhood Caries in Primary Healthcare: A Community-based Randomized Cluster Trial. J. Pediatr. 2018, 201, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, K.; Jackson, R. The health belief model and determinants of oral hygiene practices and beliefs in preteen children: A pilot study. Pediatr. Dent. 2015, 37, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, B.; Baker, S.R.; Lindberg, P.; Oscarson, N.; Öhrn, K. Factors influencing oral hygiene behaviour and gingival outcomes 3 and 12 months after initial periodontal treatment: An exploratory test of an extended Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.; Parker, E.J.; Steffens, M.A.; Logan, R.M.; Brennan, D.; Jamieson, L.M. Development and psychometric validation of social cognitive theory scales in an oral health context. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wade, K.J. Oral hygiene behaviours and readiness to change using the TransTheoretical Model (TTM). N. Z. Dent. J. 2013, 109, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Armfield, J.M.; Parker, E.J.; Roberts-Thomson, K.F.; Broughton, J.; Lawrence, H.P. Development and evaluation of the Stages of Change in Oral Health instrument. Int. Dent. J. 2014, 64, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghibi Sistani, M.M.; Yazdani, R.; Virtanen, J.; Pakdaman, A.; Murtomaa, H. Determinants of Oral Health: Does Oral Health Literacy Matter? ISRN Dent. 2013, 2013, 249591–249596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C.; Ntoumanis, N. The role of self-determined motivation in the understanding of exercise-related behaviours, cognitions and physical self-evaluations. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magill, M.; Gaume, J.; Apodaca, T.R.; Walthers, J.; Mastroleo, N.R.; Borsari, B.; Longabaugh, R. The Technical Hypothesis of Motivational Interviewing: A Meta-Analysis of MI’s Key Causal Model. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 973–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rose, G.S. Toward a Theory of Motivational Interviewing. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R. Motivational Interviewing with Problem Drinkers. Behav. Psychother. 1983, 11, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, W.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed. J. Healthc. Qual. 2003, 25, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, P.; Harrison, R.; Benton, T. Motivating mothers to prevent caries: Confirming the beneficial effect of counseling. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2006, 137, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, P.; Harrison, R.; Benton, T. Motivating parents to prevent caries in their young children: One-year findings. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martins, R.K.; McNeil, D.W. Review of Motivational Interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. ix, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Moyers, T.B. Eight Stages in Learning Motivational Interviewing. J. Teach. Addict. 2006, 5, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hardcastle, S.; Blake, N.; Hagger, M.S. The effectiveness of a motivational interviewing primary-care based intervention on physical activity and predictors of change in a disadvantaged community. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 35, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horowitz, L.G.; Dillenberg, J.; Rattray, J. Self-care Motivation: A Model for Primary Preventive Oral Health Behavior Change. J. Sch. Health 1987, 57, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Brega, A.G.; Batliner, T.S.; Henderson, W.; Campagna, E.J.; Fehringer, K.; Gallegos, J.; Daniels, D.; Albino, J. Assessment of parental oral health knowledge and behaviors among American Indians of a Northern Plains tribe. J. Public Health Dent. 2014, 74, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albino, J.; Tiwari, T. Preventing Childhood Caries: A Review of Recent Behavioral Research. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albino, J.; Tiwari, T.; Henderson, W.G.; Thomas, J.F.; Braun, P.A.; Batliner, T.S. Parental psychosocial factors and childhood caries prevention: Data from an American Indian population. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2018, 46, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henshaw, M.M.; Borrelli, B.; Gregorich, S.E.; Heaton, B.; Tooley, E.M.; Santo, W.; Cheng, N.F.; Rasmussen, M.; Helman, S.; Shain, S.; et al. Randomized Trial of Motivational Interviewing to Prevent Early Childhood Caries in Public Housing. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2018, 3, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Roberts-Thomson, K.F. Dental general anaesthetic trends among Australian children. BMC Oral Health 2006, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Do, L.G.; Spencer, J. Oral Health of Australian Children: The National Child Oral Health Study 2012–14; The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, South Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdadi, Z.D. Effects of Dental Rehabilitation under General Anesthesia on Children’s Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Using Proxy Short Versions of OHRQoL Instruments. Sci. World 2013, 2014, 308439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarimi, H.A.; Watt, R.G.; Pikhart, H.; Sheiham, A.; Tsakos, G. Dental caries and growth in school-age children. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e616–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroth, R.J.; Harrison, R.L.; Moffatt, M.E.K. Oral Health of Indigenous Children and the Influence of Early Childhood Caries on Childhood Health and Well-being. Pediatric Clin. N. Am. 2009, 56, 1481–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, A.M.; Martin-Kerry, J.; Geale, A.; Cole, D. Flying blind: Trying to find solutions to Indigenous oral health. Aust. Health Rev. 2016, 40, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, P.F.; Feldens, C.A.; Helena Ferreira, S.; Bervian, J.; Rodrigues, P.H.; Peres, M.A. Exploring the impact of oral diseases and disorders on quality of life of preschool children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2013, 41, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, D.L. Reducing Alaska Native paediatric oral health disparities: A systematic review of oral health interventions and a case study on multilevel strategies to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Batliner, T.; Fehringer, K.A.; Tiwari, T.; Henderson, W.G.; Wilson, A.; Brega, A.G.; Albino, J. Motivational interviewing with American Indian mothers to prevent early childhood caries: Study design and methodology of a randomized control trial. Trials 2014, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moynihan, P. Sugars and Dental Caries: Evidence for Setting a Recommended Threshold for Intake. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts-Thomson, K.F.; Spencer, A.J.; Jamieson, L.M. Oral health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Med J. Aust. 2008, 188, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.H.; Do, L.G.; Roberts-Thomson, K.; Jamieson, L. Risk indicators for untreated dental decay among Indigenous Australian children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2019, 47, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruerd, B.; Jones, C. Preventing baby bottle tooth decay: Eight-year results. Public Health Rep. 1996, 111, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Isong, I.A.; Luff, D.; Perrin, J.M.; Winickoff, J.P.; Ng, M.W. Parental Perspectives of Early Childhood Caries. Clin. Pediatrics 2012, 51, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Fredericks, B.; Mills, K.; Anderson, D. “Yarning” as a Method for Community-Based Health Research With Indigenous Women: The Indigenous Women’s Wellness Research Program. Health Care Women Int. 2014, 35, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R.; Benton, T.; Everson-Stewart, S.; Weinstein, P. Effect of Motivational Interviewing on Rates of Early Childhood Caries: A Randomized Trial. Pediatr. Dent. 2007, 29, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, M. Conversation Method in Indigenous Research. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2010, 5, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal, J.J.; Bowen, D.M. Motivational Interviewing to Decrease Parental Risk-Related Behaviors for Early Childhood Caries. J. Dent. Hyg. 2010, 84, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saffari, M.; Sanaeinasab, H.; Mobini, M.; Sepandi, M.; Rashidi-Jahan, H.; Sehlo, M.G.; Koenig, H.G. Effect of a health-education program using motivational interviewing on oral health behavior and self-efficacy in pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 128, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, J.; Chong, A.; Parker, E.; Roberts-Thomson, K.; Misan, G.; Spencer, J.; Broughton, J.; Lawrence, H.; Jamieson, L. Reducing disease burden and health inequalities arising from chronic disease among Indigenous children: An early childhood caries intervention. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jamieson, L.; Smithers, L.; Hedges, J.; Parker, E.; Mills, H.; Kapellas, K.; Lawrence, H.P.; Broughton, J.R.; Ju, X. Dental Disease Outcomes Following a 2-Year Oral Health Promotion Program for Australian Aboriginal Children and Their Families: A 2-Arm Parallel, Single-blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2018, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jamieson, L.M.; Hedges, J.; Ju, X.; Kapellas, K.; Leane, C.; Haag, D.G.; Santiago, P.R.; Macedo, D.M.; Roberts, R.M.; Smithers, L.G. Cohort profile: South Australian Aboriginal Birth Cohort (SAABC)—A prospective longitudinal birth cohort. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santacroce, S.J.; Maccarelli, L.M.; Grey, M. Intervention Fidelity. Nurs. Res. 2004, 53, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, L.; Bradshaw, J.; Lawrence, H.; Broughton, J.; Venner, K. Fidelity of Motivational Interviewing in an Early Childhood Caries Intervention Involving Indigenous Australian Mothers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaume, J.M.A.; Gmel, G.P.D.; Faouzi, M.P.D.; Daeppen, J.-B.M.D. Counselor skill influences outcomes of brief motivational interventions. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2009, 37, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crego, A.; Carrillo-Díaz, M.; Armfield, J.M.; Romero, M. From public mental health to community oral health: The impact of dental anxiety and fear on dental status. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vigu, A.; Stanciu, D. When the fear of dentist is relevant for more than one’s oral health. A structural equation model of dental fear, self-esteem, oral-health-related well-being, and general well-being. Patient Prefer. Adher. 2019, 13, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuyama, Y.; Jürges, H.; Dewey, M.; Listl, S. Causal effect of tooth loss on depression: Evidence from a population-wide natural experiment in the USA. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarasena, N.; Kapellas, K.; Brown, A.; Skilton, M.R.; Maple-Brown, L.J.; Bartold, M.P.; O’Dea, K.; Celermajer, D.; Slade, G.D.; Jamieson, L. Psychological distress and self-rated oral health among a convenience sample of Indigenous Australians. J. Public Health Dent. 2015, 75, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durey, A.; McAullay, D.; Gibson, B.; Slack-Smith, L.M. Oral Health in Young Australian Aboriginal Children: Qualitative Research on Parents’ Perspectives. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2017, 2, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrine, C.; Durey, A.; Slack-Smith, L. Enhancing oral health for better mental health: Exploring the views of mental health professionals. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; Marino, R.; Satur, J. Oral health promotion practices of Australian community mental health professionals: A cross sectional web-based survey. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meldrum, R.; Ho, H.; Satur, J. The role of community mental health services in supporting oral health outcomes among consumers. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butten, K.; Johnson, N.W.; Hall, K.K.; Toombs, M.; King, N.; O’Grady, K.-A.F. Impact of oral health on Australian urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, A.; Walker, D.; Tucker, T.; Fisher, B.; Fisher, T. Factors influencing the perceived importance of oral health within a rural Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Australia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshman, Z.; Ahern, S.M.; McEachan, R.R.C.; Rogers, H.J.; Gray-Burrows, K.A.; Day, P.F. Parents’ Experiences of Toothbrushing with Children: A Qualitative Study. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2016, 1, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butten, K.; Johnson, N.W.; Hall, K.K.; Toombs, M.; King, N.; O’Grady, K.-A.F. Yarning about oral health: Perceptions of urban Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durey, A.; McAullay, D.; Gibson, B.; Slack-Smith, L. Aboriginal Health Worker perceptions of oral health: A qualitative study in Perth, Western Australia. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durey, A.; Bessarab, D.; Slack-Smith, L. The mouth as a site of structural inequalities; the experience of Aboriginal Australians. Community Dent. Health 2016, 33, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cidro, J.; Zahayko, L.; Lawrence, H.; McGregor, M.; McKay, K. Traditional and cultural approaches to childrearing: Preventing early childhood caries in Norway House Cree Nation, Manitoba. Rural Remote Health 2014, 14, 2968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.; McNally, M.; Castleden, H.; Worden-Driscoll, I.; Clarke, M.; Wall, D.; Ley, M. Linking Inuit Knowledge and Public Health for Improved Child and Youth Oral Health in NunatuKavut. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2018, 3, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, R.J.; Halchuk, S.; Star, L. Prevalence and risk factors of caregiver reported Severe Early Childhood Caries in Manitoba First Nations children: Results from the RHS Phase 2 (2008–2010). Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, J.R.; Person, M.; Maipi, J.T.H.; Cooper-Te, K.R.; Smith-Wilkinson, A.; Tiakiwai, S.; Kilgour, J.; Berryman, K.; Morgaine, K.C.; Jamieson, L.M.; et al. Ukaipō niho: The place of nurturing for oral health. N. Z. Dent. J. 2014, 110, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Peres, M.A.; Macpherson, L.M.D.; Weyant, R.J.; Daly, B.; Venturelli, R.; Mathur, M.R.; Listl, S.; Celeste, R.K.; Guarnizo-Herreño, C.C.; Kearns, C.; et al. Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 2019, 394, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elani, H.W.; Harper, S.; Thomson, W.M.; Espinoza, I.L.; Mejia, G.C.; Ju, X.; Jamieson, L.M.; Kawachi, I.; Kaufman, J.S. Social inequalities in tooth loss: A multinational comparison. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poirier, B.F.; Hedges, J.; Smithers, L.G.; Moskos, M.; Jamieson, L.M. Aspirations and Worries: The Role of Parental Intrinsic Motivation in Establishing Oral Health Practices for Indigenous Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111695

Poirier BF, Hedges J, Smithers LG, Moskos M, Jamieson LM. Aspirations and Worries: The Role of Parental Intrinsic Motivation in Establishing Oral Health Practices for Indigenous Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111695

Chicago/Turabian StylePoirier, Brianna F., Joanne Hedges, Lisa G. Smithers, Megan Moskos, and Lisa M. Jamieson. 2021. "Aspirations and Worries: The Role of Parental Intrinsic Motivation in Establishing Oral Health Practices for Indigenous Children" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111695

APA StylePoirier, B. F., Hedges, J., Smithers, L. G., Moskos, M., & Jamieson, L. M. (2021). Aspirations and Worries: The Role of Parental Intrinsic Motivation in Establishing Oral Health Practices for Indigenous Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11695. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111695