Understanding the Relationship between Depression and Chronic Diseases Such as Diabetes and Hypertension: A Grounded Theory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mechanisms of Influence: Chronic Diseases → Depression

1.2. Mechanisms of Influence: Depression -→ Chronic Diseases

1.3. Common Causal Mechanisms

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling Strategy and Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Collection Instruments

2.4.1. Diagnostic Instrument for Patients

2.4.2. Data Collection Instruments for Patients and Health Professionals

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

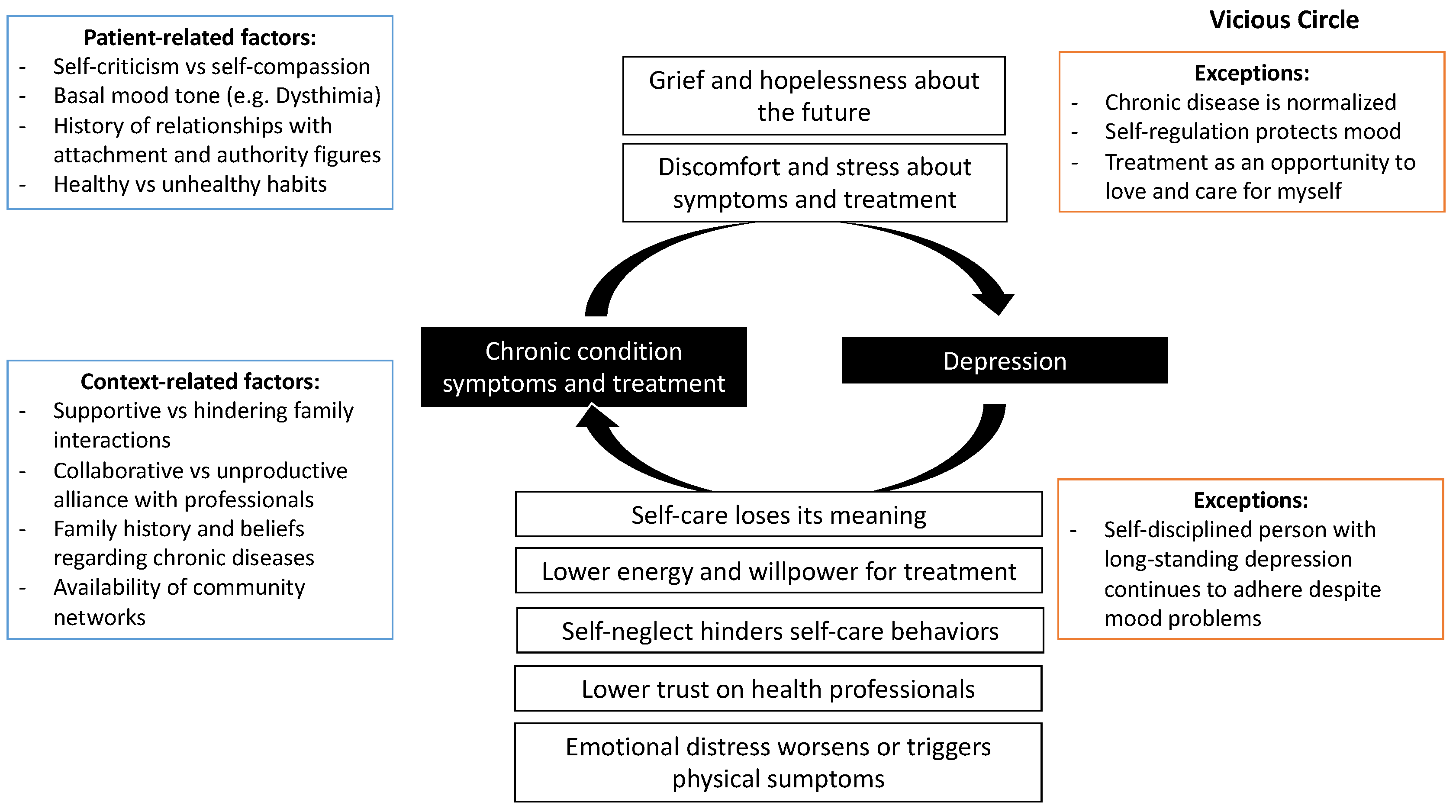

3.1. Vicious Circle: Bidirectional Relationship between Mood Problems and Difficulties with the Management of Chronic Disease

3.1.1. The Ways Chronic Disease Affects Mood

Chronic Illness Produces Grief and Hopelessness about the Future

“I have a vision problem. Suddenly, I say that it’s best if I’m no longer alive, because I’m going to be a burden. If I go blind, I’m going to be a burden and I don’t want to be.”(E4)

[On how he reacted when his diabetes was confirmed] “... I didn’t want it. I didn’t even want to see a doctor. I had no idea that I had to be with a nutritionist or anything. So, it bothered me, and I was scared about what to do. So that’s how I spent many years. (...) Suddenly, I was taking [the medications] and other times I was not taking them. I have to be very honest about that, because I was angry, upset... Why did I get sick like that?”(E9)

Chronic Illness Causes Discomfort and Stress

“... But one doesn’t have time. Vegetables—do not eat this vegetable, do not eat the other vegetable. In the end, I don’t eat vegetables, I just like lettuce... tomatoes, generally, tomatoes. But I can’t eat tomatoes either because tomatoes are too sweet. Corn is also sweet. So, in the end, what does one eat?”(E6)

3.1.2. The Ways Mood Problems Affect the Evolution of Chronic Diseases and/or Adherence to Their Treatment

Depression Makes You Feel It Is Pointless to Take Care of Yourself

“If one day you see everything black and you see that it will not change at all, that your life has no meaning. It does not matter to you if you dialyze yourself or not, or if you follow the instructions or not, if in the end what you want is to stop living”.(EntProf2)

Maintaining a Healthy Lifestyle Requires Too Much Effort for the Depressed Person

“You still feel lonely because nobody understands you in the end. Because they are judging you because you are fat. For example, my mom didn’t believe me when I told her that I suffered from anxiety. And she told me: ‘you must stop eating so much’. And I tell her: ‘ah, but it’s not that easy’ (...) Besides, the endocrinologist says things a bit harsher. They say: ‘now, take this…do it’”.(Ent5)

Patients with Depression Are Distrustful of Authority Figures, Making It Difficult to Collaborate with Health Professionals

“Patients who do not adhere to treatment or sessions or whatever, it is because they have had bad experiences, either with doctors, with the health center, the hospital or whoever. Then with those bad experiences like, I don’t know … As they already begin to reject the consultation a little.”(GF4)

[Why did you make the decision to stop seeing your doctor?] “I didn’t want to live my whole life taking pills. I don’t want to live my whole life thinking ‘NO! YOU CAN’T EAT THIS, LEAVE IT THERE!’ Because many people are like that. Even my mom: “you can’t eat that.” It makes me sick (nervous laugh), so I didn’t want to live like this, that is, I preferred to die but not live like this. Because it’s not easy”.(Ent15)

Self-Neglect Patterns Hinder Self-Care Behaviors

(...) “I spent many years worrying more than one hundred percent about him and not caring about myself. (…) I worried about him taking the exams, about his meals, about everything. And I... I forgot the date of... to go to the nurse, to go to the doctor. Then I realized… I failed to go to the doctor’s appointment.”(Ent9)

The Body Manifests the Consequences of Emotional Distress

“I told him I have triglycerides sky high and diabetes sky high, and it is because I was not calm. (...) I had no time for anything. My day was nothing. I lacked hours a day to continue doing things. (...) So, I think that neuroses are involved a lot. Yes, because I get nervous. And everything raises your sugar”.(Ent7)

3.1.3. Contextual Factors

3.2. Exceptions

3.2.1. Cases in Which the Chronic Disease Does Not Adversely Affect Mood

Chronic Disease Is Normalized or Does Not Imply a Big Change in Daily Habits

“But it happened to me after my 60th birthday. That is why I say that it has not been an issue for me.”(E4)

Treatment as an Opportunity to Care for and Love Myself

“My life was always about home, son, work, son, work, home, work... so it was very busy, and I never worried about myself (...) I started there and finally said ‘no’, now I’m going to start caring about me. They are all doing great, I have no greater responsibility, so I’m going to start with my own affairs. And that’s when I started to look out for myself.”(E2)

Self-Regulation Ability Protects Mood

“She [her daughter] arrives with delicious things, …a lemon pie, a kuchen, … a milk cake, prepared by her. And she says to me: ‘look mom, see what I brought’. But if you are going to give me something, I say, me, give me only a bit, the size of a box of matches. And yes, I accept a bit of cake, so I don’t hurt her feelings. I say thank you, because it doesn’t complicate life for me, because it’s not so much and it’s not every day. What else can I do?”(E8)

3.2.2. Cases in Which Mood Problems Do Not Affect Chronic Diseases

A Self-Disciplined Person with a Long-Standing “Normalized” Depressive State Continues Her Treatment despite Feeling Bad

“I always take the medicine. Even if I have all the problems I have, but I always do the same... I have never stopped taking the medicines. (...) Calm or desperate, I don’t know. But I always take the medicine. I am not irresponsible in taking the pills.”(Ent10)

3.3. Suggested and Experienced Therapeutic Strategies

3.3.1. Acknowledge the Loss and Grief Process

“... the idea of helping him so that that person can acknowledge that ‘loss’, regarding his image of himself, his lifestyle and everything in a way that he can continue living with it. Give the person time to experience the grief and accompany him in that and not expect the person to accept it immediately, knowing that grief also has its processes.”(EntProf2)

3.3.2. Promote Empowerment and Hope

“She became depressed thinking that complications could lead to amputations, loss of sight (...). She had to first learn to live with her disease and to be able to cope with all the changes associated with it, such as eating, mealtimes, check-ups, and then she realized that if she kept her condition stable, she would be fine, she wouldn’t have complications.”(GF1)

3.3.3. Support the Patient’s Context (Family, Community) so That the Person Requires Less Effort to Follow Their Treatment

“My mother says that it is a disease for people who are old, not for the young. And besides, I have a lot of family who are diabetic, a lot. So, my mom always tells me: look, you want to end up like them? [family members with diabetes]. (…) since I don’t take care of myself and all those things. And my mom is nagging. (...) So when my mom says those things to me, she hurts me a lot. Like: do you want to look like your aunt? (…) I start to cry.”(Ent5)

“So, my husband is involved in my [treatment] plan. He also helps me jog. He puts the TV on for me, he puts on music so that I don’t get bored. (...) Since there are not many of us at home, there is awareness on the part of my husband, which is the main thing. Sometimes, when my son wants to eat food that’s bad for me, he says ‘mommy, don’t wait for me with food, because I’ve already had lunch, or I’ve already eaten’.”(Ent8)

4. Conclusions

4.1. Acknowledge and Support the Patient’s Grieving Process

4.2. Support the Patient’s Management of Treatment-Related Stress and Demands

4.3. The Importance of “Exceptions” and Tailored Treatment

4.4. Final Words

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Health Statistics and Information (DEIS). Indicadores Básicos de Salud Chile 2016 [Basic health indicators Chile 2016]. 2016. Available online: http://www.deis.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IBS-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Martínez, P.; Rojas, G.; Fritsch, R.; Martínez, V.; Vöhringer, P.; y Castro, A. Comorbilidad en personas con depresión que consultan en centros de la atención primaria de salud en Santiago, Chile. Rev. Med. Chile 2017, 145, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katon, W.J. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 13, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (MINSAL). Guía Clínica Depresión GES [GES Depression Clinical Guide]. 2013. Available online: http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/GUIA-CLINICA-DEPRESION-15-Y-MAS.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Darwish, L.; Beroncal, E.; Sison, M.V.; Swardfager, W. Depression in people with type 2 diabetes: Current perspectives. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gask, L.; Macdonald, W.; Bower, P. What is the relationship between diabetes and depression? A qualitative meta-synthesis of patient experience of co-morbidity. Chronic Illn. 2011, 7, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, R.; de Groot, M.; Golden, S.H. Diabetes and Depression. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJean, D.; Giacomini, M.; Vanstone, M.; Brundisini, F. Patient experiences of depression and anxiety with chronic disease: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2013, 13, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, S.; Friedman, M.A.; Arent, S.M. Understanding the relation between obesity and depression: Causal mechanisms and implications for treatment. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2008, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, C.D.; Pickup, J.C.; Ismail, K. The link between depression and diabetes: The search for shared mechanisms. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penckofer, S.; Quinn, L.; Byrn, M.; Ferrans, C.; Miller, M.; Strange, P. Does glycemic variability impact mood and quality of life? Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2012, 14, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bădescu, S.V.; Tătaru, C.; Kobylinska, L.; Georgescu, E.L.; Zahiu, D.M.; Zăgrean, A.M.; Zăgrean, L. The association between Diabetes mellitus and Depression. J. Med. Life 2016, 9, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Corveleyn, J.; Luyten, P.; Blatt, S.J.; Blatt, S.J. The Theory and Treatment of Depression; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S.; Rice, L.N.; Elliott, R. Facilitando el Cambio Emocional [Facilitating Emotional Change]; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dagnino, P.; Pérez, C.; Gómez, A.; Gloger, S.; Krause, M. Depression and attachment: How do personality styles and social support influence this relation? Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. Process. Outcome 2017, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ehret, A.M.; Joormann, J.; Berking, M. Examining risk and resilience factors for depression: The role of self-criticism and self- compassion. Cogn. Emot. 2015, 29, 1496–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, A.; Westra, H. The impact of motivational interviewing on resistance in cognitive behavioural therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother. Res. 2011, 21, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, P. Cooperation and Resistance toward Medical Treatment in Hypertensive Patients Who Require Lifestyle Changes; Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- San Martín, D. Teoría fundamentada y Atlas.ti: Recursos metodológicos para la investigación educativa [Grounded theory and Atlas.ti: Methodological resources for educational research]. Rev. Electron. Investig. Educativa. 2014, 16. Available online: https://redie.uabc.mx/redie/article/view/727/891 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Bases de la Investigación Cualitativa: Técnicas y Procedimientos Para Desarrollar la Teoría Fundamentada [Bases of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures to Develop Grounded Theory]; Sage; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellín, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, D.L. The importance of symbolic interaction in grounded theory research on women’s health. Health Care Women Int. 2001, 22, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, P.; Moncada, L.; Defey, D. Understanding Non-Adherence from the Inside: Hypertensive Patients’ Motivations for Adhering and Not Adhering. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 27, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baader, T.; Molina, J.; Venezian, S.; Rojas, C.; Farías, R.; Fierro-Freixenet, C.; Backenstrass, M.; Mundt, C. Validación y utilidad de la encuesta PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) en el diagnóstico de depresión en usuarios de atención primaria en Chile [Validation and usefulness of the PHQ-9 survey (Patient Health Questionnaire) in the diagnosis of depression in primary care users in Chile.]. Rev. Chil. De Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2012, 50, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, D. El dilema de lo cuantitativo y lo cualitativo de las encuestas a los métodos rápidos de investigación en salud [The quantitative and qualitative dilemma of surveys of rapid health research methods]. In Ciencias Sociales y Medicina. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas [Social Science and Medicine. Latinoamerican Perspecives]; Lolas, F., Florenzano, R., Gyarmati, G., Trejo, C., Eds.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 1992; pp. 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.; Magilvy, J.K. Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2011, 16, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Rush, A.J.; Shaw, B.; Emery, G. Cognitive Therapy for Depression, 19th ed.; Desclée de Brouwer: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, K.; Rose, A.; Peters, N.; Long, J.A.; McMurphy, S.; Shea, J.A. Distrust of the health care system and self-reported health in the United States. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, S. Saying goodbye in Gestalt therapy. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1971, 8, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, J.W. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy, 5th ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, R.; Weakland, J.H.; Segal, L.; Segal, L. The Tactic of Change; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Grulke, N.; Bailer, H.; Hertenstein, B.; Kächele, H.; Arnold, R.; Tschuschke, V.; Heimpel, H. Coping and survival in patients with leukemia undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation—long-term follow-up of a prospective study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 59, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.T.; Frame, M.C. Stress, health, and job performance: What do we know? J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2018, 23, 12147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, I.; Campos, S.; Urrutia, M.; Bustamante, C.; Alcayaga, C.; Tellez, Á.; Pérez, J.C.; Villarroel, L.; Chamorro, G.; O’Connor, A.; et al. Efecto de un modelo de apoyo telefónico en el auto-manejo y control metabólico de la Diabetes tipo 2, en un Centro de Atención Primaria, Santiago, Chile. Rev. Med. De Chile 2010, 138, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Leppin, A.; Montori, V.; Gionfriddo, M. Minimally Disruptive Medicine: A Pragmatically Comprehensive Model for Delivering Care to Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Healthcare 2015, 3, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.J. Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment Regimens. Bridging the Gap between Behavioral Science and Biomedicine; Yale University Press: Lonodn, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M.; Lukwago, S.; Bucholtz, R.; Clark, E.; Sanders-Thompson, V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, M.; Huntink, E.; van Lieshout, J.; Godycki-Cwirko, M.; Kowalczyk, A.; Jäger, C.; Steinhäuser, J.; Aakhus, E.; Flottorp, S.; Eccles, M.; et al. Tailored implementation of evidence-based practice for patients with chronic diseases. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wensing, M. The Tailored Implementation in Chronic Diseases (TICD) project: Introduction and main findings. Implement. Sci. 2017, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, P.; Prochaska, J.O.; Rossi, J.S. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piette, J.D.; Richardson, C.; Valenstein, M. Addressing the needs of patients with multiple chronic illnesses: The case of diabetes and depression. Am. J. Manag. Care 2004, 10, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera, P.A.; Campos-Romero, S.; Szabo, W.; Martínez, P.; Guajardo, V.; Rojas, G. Understanding the Relationship between Depression and Chronic Diseases Such as Diabetes and Hypertension: A Grounded Theory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212130

Herrera PA, Campos-Romero S, Szabo W, Martínez P, Guajardo V, Rojas G. Understanding the Relationship between Depression and Chronic Diseases Such as Diabetes and Hypertension: A Grounded Theory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212130

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera, Pablo Alberto, Solange Campos-Romero, Wilsa Szabo, Pablo Martínez, Viviana Guajardo, and Graciela Rojas. 2021. "Understanding the Relationship between Depression and Chronic Diseases Such as Diabetes and Hypertension: A Grounded Theory Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212130

APA StyleHerrera, P. A., Campos-Romero, S., Szabo, W., Martínez, P., Guajardo, V., & Rojas, G. (2021). Understanding the Relationship between Depression and Chronic Diseases Such as Diabetes and Hypertension: A Grounded Theory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212130