A Successful Dental Care Referral Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women in New York

Abstract

:1. Introduction

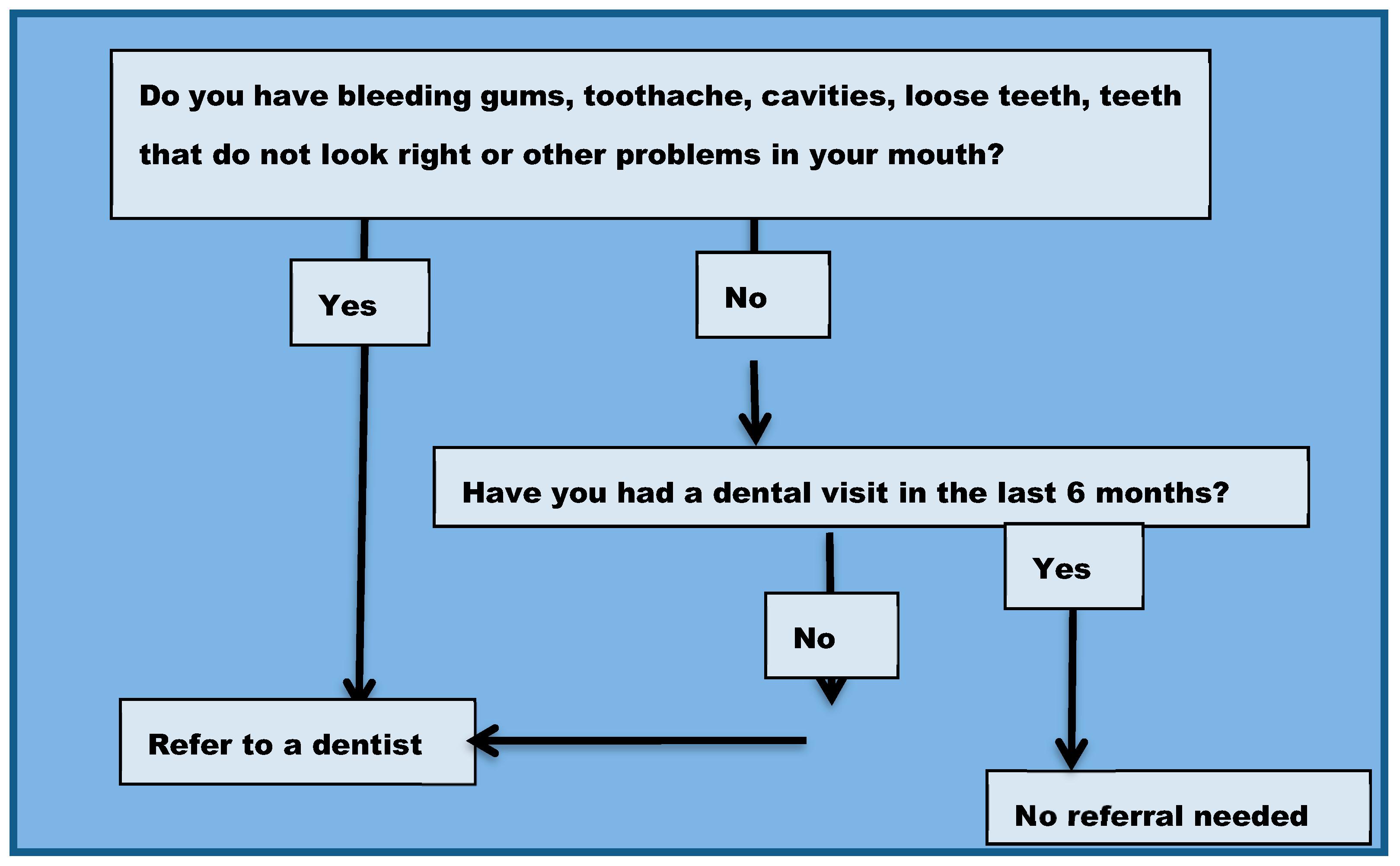

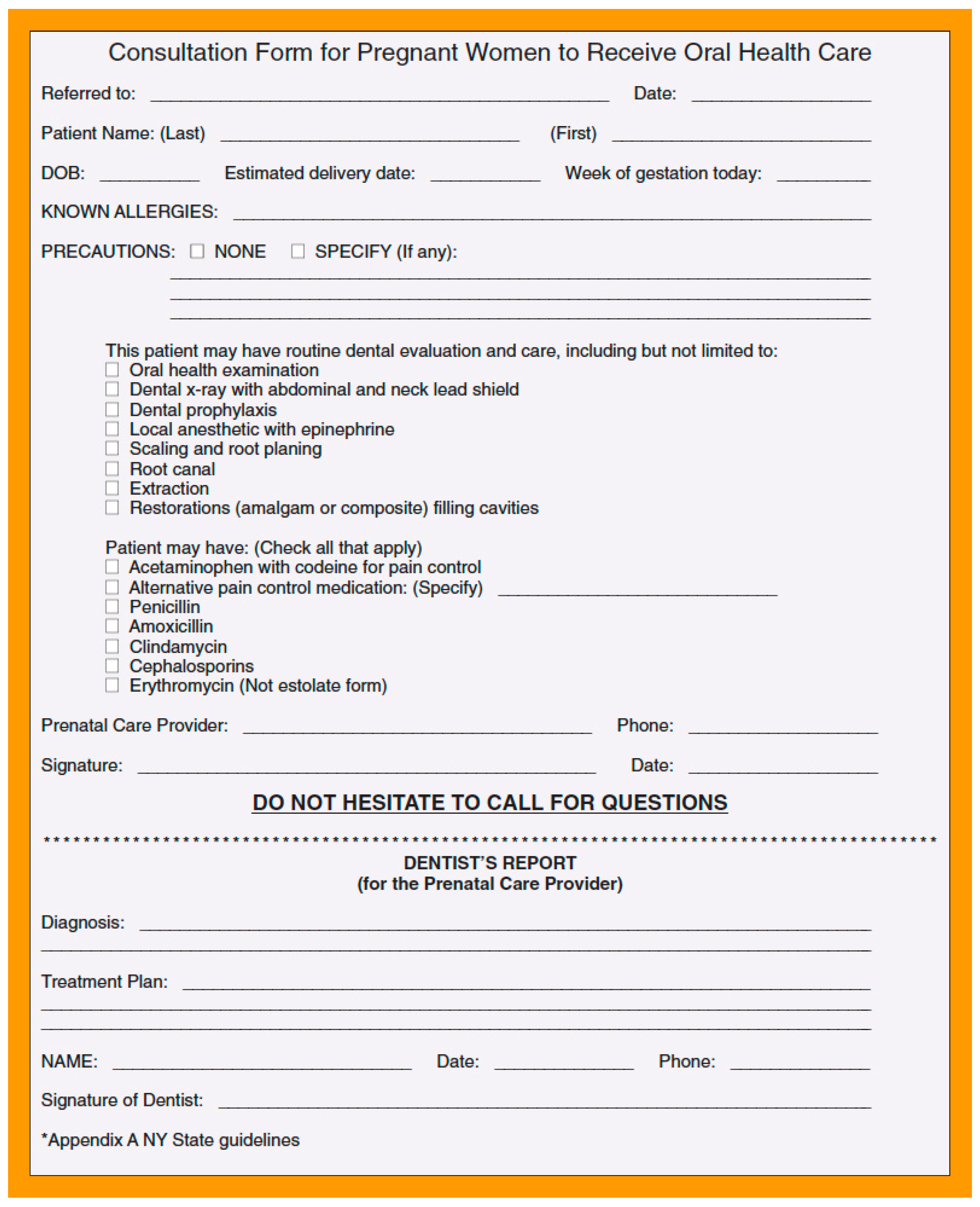

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

3.2. Bivariate Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, S.L.; Ickovics, J.; Yaffee, R. Parity and Tooth Loss: Exploring Potential Pathways in American Women. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.L.; Gordon, S.; Lukacs, J.R.; Kaste, L.M. Sex/Gender Differences in Tooth Loss and Edentulism: Historical Perspectives, Biological Factors, and Sociologic Reasons. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 57, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva de Araujo Figueiredo, C.; Gonçalves Carvalho Rosalem, C.; Costa Cantanhede, A.L.; Abreu Fonseca Thomaz, É.B.; Fontoura Nogueira da Cruz, M.C. Systemic alterations and their oral manifestations in pregnant women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raju, K.; Berens, L. Periodontology and pregnancy: An overview of biomedical and epidemiological evidence. Periodontol 2000 2021, 87, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azofeifa, A.; Yeung, L.F.; Alverson, C.J.; Beltrán-Aguilar, E. Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease among U.S. Pregnant Women and Nonpregnant Women of Reproductive Age, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. J. Public Health Dent. 2016, 76, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, Y.; Xiong, X.; Elkind-Hirsch, K.E.; Pridjian, G.; Maney, P.; Delarosa, R.L.; Buekens, P. Change of Periodontal Disease Status during and After Pregnancy. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farland, L.V.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Gillman, M.W. Early Pregnancy Cravings, Dietary Intake, and Development of Abnormal Glucose Tolerance. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1958–1964.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonbul, H.; Ashi, H.; Aljahdali, E.; Campus, G.; Lingström, P. The Influence of Pregnancy on Sweet Taste Perception and Salivary Acidogenicity. Matern. Child Health 2017, 21, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- New York State Department of Health. Oral Health Care during Pregnancy and Early Childhood. Practice Guidelines, 2006. Available online: https://www.health.ny.gov/prevention/dental/oral_health_care_pregnancy_early_childhood.htm (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Oral health care during pregnancy and through the lifespan. Committee Opinion No. 569. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalowicz, B.S.; DiAngelis, A.J.; Novak, M.J.; Buchanan, W.; Papapanou, P.N.; Mitchell, D.A.; Curran, A.E.; Lupo, V.R.; Ferguson, J.E.; Bofill, J. Examining the safety of Dental Treatment in Pregnant Women. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenbacher, S.; Lin, D.; Strauss, R.; McKaig, R.; Irving, J.; Barros, S.P.; Moss, K.; Barrow, D.A.; Hefti, A.; Beck, J.D. Effects of Periodontal Therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters & pregnancy outcome. J. Periodontics 2006, 77, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar]

- Iida, H.; Kumar, J.V.; Radigan, A.M. Oral health during perinatal period in New York State. Evaluation of 2005 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data. N. Y. State Dent. J. 2009, 75, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marchi, K.S.; Fisher-Owens, S.A.; Weintraub, J.A.; Yu, Z.; Braveman, P.A. Most pregnant women in California do not receive dental care: Findings from a population-based study. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Tranby, E.; Shi, L. Dental Visits during Pregnancy: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Analysis 2012–2015. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Garcia, A.I.; Adams, A.B.; Cheng, D. Disparities in unmet dental need and dental care received by pregnant women in Maryland. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerpen, S.J.; Burakoff, R. Improving access to oral health care for pregnant women. A private practice model. N. Y. State Dent. J. 2009, 75, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Boggess, K.A.; Urlaub, D.M.; Massey, K.E.; Moos, M.K.; Matheson, M.B.; Lorenz, C. Oral hygiene practices and dental service utilization among pregnant women. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2010, 141, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dye, B.A.; Li, X.; Thorton-Evans, G. Oral Health Disparities as Determined by Selected Healthy People 2020 Oral Health Objectives for the United States, 2009–2010; NCHS Data Brief, No. 104; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D.J.; O’Hayre, M.; Kusiak, J.W.; Somerman, M.J.; Hill, C.V. Oral Health Disparities: A Perspective from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S36–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibulka, N.J.; Forney, S.; Goodwin, K.; Lazaroff, P.; Sarabia, R. Improving oral health in low-income pregnant women with a nurse practitioner-directed oral care program. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2011, 23, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.T.; Quinonez, R.B.; Kerns, A.K.; Chuang, A.; Eidson, R.S.; Boggess, K.A.; Weintraub, J.A. Implementing a prenatal oral health program through interprofessional collaboration. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 79, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Schaaf, E.B.; Quinonez, R.B.; Cornett, A.C.; Randolph, G.D.; Boggess, K.; Flower, K.B. A Pilot Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve Safety Net Dental Access for Pregnant Women and Young Children. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Dahlen, H.G.; Blinkhorn, A.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Ellis, S.; Yeo, A.; Elcombe, E.; Johnson, M. Evaluation of a midwifery initiated oral health-dental service program to improve oral health and birth outcomes for pregnant women: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, C.A.; Weinstein, P.; Mancl, L.; Garson, G.; Huebner, C.E.; Milgrom, P.; Grembowski, D.; Shepherd-Banigan, M.; Smolen, D.; Sutherland, M. Dental attendance among low-income women and their children following a brief motivational counseling intervention: A community randomized trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 144, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kerpen, S.J.; Burakoff, R. Providing oral health care to underserved population of pregnant women: Retrospective review of 320 patients treated in private practice setting. N. Y. State Dent. J. 2013, 79, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristics | Total (n = 298) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± ds) | 26.5 ± 5.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | % (n) |

| White | 10.7% (31) |

| Black | 29.4% (86) |

| Asian | 12.8% (37) |

| Hispanic | 39.1% (113) |

| Place of Birth | |

| USA, including PR | 52.5% (156) |

| Education | |

| <HS graduate | 18.2% (53) |

| HS graduate/Some college | 62.5% (182) |

| ≥College graduate | 19.2% (56) |

| Family Income | |

| ≤10,000 USD/year | 28.9% (86) |

| 10,001–20,000 USD/year | 33.2% (99) |

| ≥20,000/year | 30.8% (92) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/living as married | 77.7% (226) |

| Language | |

| English | 87.2% (259) |

| Spanish | 12.1% (36) |

| Place of Residence | |

| Long Island | 41.7% (123) |

| Queens (NYC) | 51.3% (153) |

| Brooklyn (NYC) | 5.7% (17) |

| Pregnancy Characteristics | |

| Gravidity (# pregnancies) | |

| 1 | 40.3% (120) |

| 2 | 29.2% (87) |

| ≥3 | 30.5% (91) |

| Parity (# live births) | |

| 0 | 53.4% (159) |

| 1 | 23.8% (71) |

| ≥2 | 22.5% (67) |

| First Prenatal Visit | |

| first trimester | 77.5% (231) |

| second trimester | 30.8% (92) |

| third trimester | 2.4% (7) |

| Trimester at Time of Survey | |

| 1 | 12.4% (37) |

| 2 | 49.0% (146) |

| 3 | 38.3% (114) |

| Pregnancy Symptoms | |

| nausea | 71.8% (214) |

| vomiting | 56.7% (169) |

| fatigue | 68.8% (205) |

| Pregnancy Complications | |

| gestational diabetes | 5.0% (15) |

| hypertension | 2.3% (7) |

| Total (n = 298) % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Perceived Oral Health | |

| excellent/very good | 27.1% (78) |

| good | 46.3% (138) |

| fair/poor | 24.2% (72) |

| Brushing Frequency | |

| ≤once daily | 4.3% (13) |

| once daily | 25.8% (77) |

| twice daily | 55.7% (166) |

| ≥twice daily | 13.8% (41) |

| Interproximal Cleaning Frequency | |

| never | 37.6% (112) |

| 1–3 times/month | 15.4% (46) |

| 1–3 times/week | 21.8% (65) |

| daily | 24.2% (72) |

| Number of Missing Teeth | |

| none | 63.4% (189) |

| 1–2 teeth | 24.3% (74) |

| ≥3 teeth | 11.4% (34) |

| Ever Told Had Gum Disease | |

| yes | 10.4% (31) |

| Dental Care When Not Pregnant | |

| never | 10.1% (30) |

| for pain or problem only | 28.9% (86) |

| ≤once yearly | 45.9% (137) |

| ≥twice yearly | 14.8% (44) |

| Usual Place of Routine Dental Care | |

| no routine care | 29.2% (87) |

| private dental office | 43.0% (128) |

| public dental clinic | 26.5% (79) |

| Difficulty Finding Place for Routine Dental Care | |

| not tried to find place for routine care | 12.4% (37) |

| not difficult | 44.3% (132) |

| somewhat difficult | 23.2% (69) |

| very difficult | 18.8% (56) |

| Method of Payment for Dental Care when not Pregnant | |

| private dental insurance | 13.1% (39) |

| Medicaid | 54.0% (161) |

| cash/self-pay | 19.8% (59) |

| could not pay/don’t know how I would pay | 9.4% (28) |

| Oral Symptoms during Current Pregnancy | |

| bleeding gums | 47.7% (142) |

| oral/dental pain | 41.6% (124) |

| swollen gums | 31.2% (93) |

| cavity | 28.5% (85) |

| loose tooth/teeth | 10.1% (30) |

| Dental Care Referral from Prenatal Clinic during Current Pregnancy | 72.5% (216) |

| Dental Visit during Current Pregnancy | 56.0% (167) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russell, S.L.; Kerpen, S.J.; Rabin, J.M.; Burakoff, R.P.; Yang, C.; Huang, S.S. A Successful Dental Care Referral Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women in New York. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312724

Russell SL, Kerpen SJ, Rabin JM, Burakoff RP, Yang C, Huang SS. A Successful Dental Care Referral Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women in New York. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312724

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussell, Stefanie L., Steven J. Kerpen, Jill M. Rabin, Ronald P. Burakoff, Chengwu Yang, and Shulamite S. Huang. 2021. "A Successful Dental Care Referral Program for Low-Income Pregnant Women in New York" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312724