Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in the Hospital Discharge after Stroke

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Primary outcome: functional independence and support needs in activities of daily living;

- -

- Secondary outcomes: improvement in sensory–motor skills, perceptual–cognitive skills, communication skills, quality of life, levels of anxiety and depression, and coping strategies and caregiver burden. At the same time, data on readmissions to the hospital, mortality, age, sex, etiology, race, income, side of hemiparesis, vascular territory and volume of the lesion, reperfusion treatment received, caregiver support, medical treatment at discharge, return to work, and return to driving are collected, as well as a direct economic analysis.

2. Relevance

3. Materials and Methods

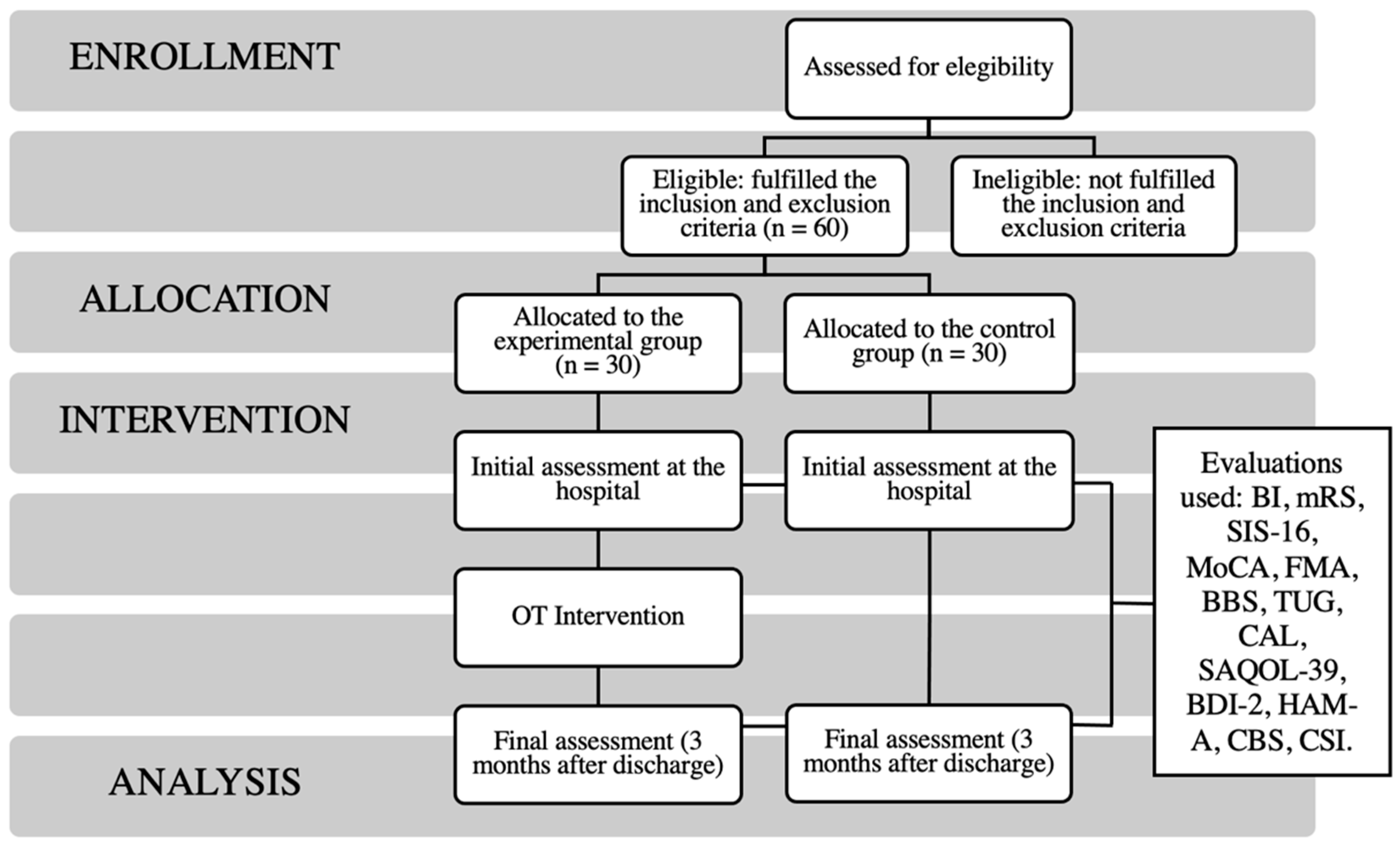

3.1. Type and General Design of the Study

3.2. Selection and Sample Size

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.4. Assessments to Be Used in the Study

3.5. Schedule and Data Collection

- -

- Before discharge: Two visits to the hospital.

- -

- Post-discharge: A post-discharge home visit, telephone follow up, a home visit one month later, and a final evaluation three months after discharge.

3.6. Temporary Planning

3.7. Data Analysis Section

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Portalfarma. Madrid: Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Available online: https://www.portalfarma.com/Profesionales/campanaspf/categorias/Documents/2017-Guia-Prevencion-Ictus.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Informe de ictus Andalucía. Sociedad Española de Neurología. Available online: https://www.sen.es/images/2020/atlas/Informes_comunidad/Informe_ICTUS_Andalucia.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Abordaje del Accidente Cerebrovascular [Internet]. Madrid: Sistema Nacional de Salud. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/docs/200204_1.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- Chu, K.; Bu, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, W.; Xiao, L.; Jiang, F.; Tang, X. Feasibility of a Nurse-Trained, Family Member-Delivered Rehabilitation Model for Disabled Stroke Patients in Rural Chongqing, China. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjelsvik, B.E.B.; Hofstad, H.; Smedal, T.; Eide, G.E.; Næss, H.; Skouen, J.S.; Frisk, B.; Daltveit, S.; Strand, L.I. Balance and Walking after Three Different Models of Stroke Rehabilitation: Early Supported Discharge in a Day Unit or at Home, and Traditional Treatment (Control). BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Anderson, C.S.; Xie, B.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Prvu Bettger, J.; et al. Caregiver-Delivered Stroke Rehabilitation in Rural China. Stroke 2019, 50, 1825–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, S.F.; Burton, L.; McGovern, A. The Effect of a Structured Programme to Increase Patient Activity during Inpatient Stroke Rehabilitation: A Phase I Cohort Study. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vloothuis, J.D.; Mulder, M.; Veerbeek, J.M.; Konijnenbelt, M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Ket, J.C.; Kwakkel, G.; van Wegen, E.E. Caregiver-mediated Exercises for Improving Outcomes after Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD011058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudzi, W.; Stewart, A.; Musenge, E. Effect of Carer Education on Functional Abilities of Patients with Stroke. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Yue, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y. Collaborative Care Model Based Telerehabilitation Exercise Training Program for Acute Stroke Patients in China: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, Á.A. Rehabilitación del ACV: Evaluación, pronóstico y tratamiento. Galicia Clínica 2009, 70, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process—Fourth Edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74 (Suppl. S2), 7412410010p1–7412410010p87. [CrossRef]

- Rafsten, L.; Danielsson, A.; Nordin, A.; Björkdahl, A.; Lundgren-Nilsson, A.; Larsson, M.E.H.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Gothenburg Very Early Supported Discharge Study (GOTVED): A Randomised Controlled Trial Investigating Anxiety and Overall Disability in the First Year after Stroke. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmussen, R.S.; Østergaard, A.; Kjær, P.; Skerris, A.; Skou, C.; Christoffersen, J.; Seest, L.S.; Poulsen, M.B.; Rønholt, F.; Overgaard, K. Stroke Rehabilitation at Home before and after Discharge Reduced Disability and Improved Quality of Life: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taule, T.; Strand, L.I.; Assmus, J.; Skouen, J.S. Ability in Daily Activities after Early Supported Discharge Models of Stroke Rehabilitation. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 22, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Almhdawi, K.A.; Mathiowetz, V.G.; White, M.; delMas, R.C. Efficacy of Occupational Therapy Task-Oriented Approach in Upper Extremity Post-Stroke Rehabilitation. Occup. Ther. Int. 2016, 23, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, Y.D.; Bouhsain, M.E.; Salcedo, I.V.; Cantín, R.C. Plan de intervención desde terapia ocupacional en un paciente afecto de hemiplejia derecha: Tratamiento rehabilitador centrado en funcionalidad de extremidad superior. Rev. Electrónica Ter. Ocup. Galicia TOG 2017, 26, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Mar, J.; Masjuan, J.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Gonzalez-Rojas, N.; Becerra, V.; Casado, M.Á.; Torres, C.; Yebenes, M.; Quintana, M.; Alvarez-Sabín, J. Outcomes Measured by Mortality Rates, Quality of Life and Degree of Autonomy in the First Year in Stroke Units in Spain. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez-Sabín, J.; Quintana, M.; Masjuan, J.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Mar, J.; Gonzalez-Rojas, N.; Becerra, V.; Torres, C.; Yebenes, M.; CONOCES Investigators Group. Economic Impact of Patients Admitted to Stroke Units in Spain. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greysen, S.R.; Stijacic Cenzer, I.; Auerbach, A.D.; Covinsky, K.E. Functional Impairment and Hospital Readmission in Medicare Seniors. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, A.T.; Bai, G.; Lavin, R.A.; Anderson, G.F. Higher Hospital Spending on Occupational Therapy Is Associated With Lower Readmission Rates. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2017, 74, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiltz, N.K.; Dolansky, M.A.; Warner, D.F.; Stange, K.C.; Gravenstein, S.; Koroukian, S.M. Impact of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Limitations on Hospital Readmission: An Observational Study Using Machine Learning. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 2865–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråndal, A.; Eriksson, M.; Glader, E.-L.; Wester, P. Effect of Early Supported Discharge after Stroke on Patient Reported Outcome Based on the Swedish Riksstroke Registry. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Langhorne, P.; Baylan, S.; Early Supported Discharge Trialists. Early Supported Discharge Services for People with Acute Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, CD000443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fearon, P.; Langhorne, P.; Early Supported Discharge Trialists. Services for Reducing Duration of Hospital Care for Acute Stroke Patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD000443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domingo García, A.M. Occupational Therapy´s Treatment in Cerebrovascular Damages. TOG -Revista de Terapia Ocupacional Galicia. 2006. Available online: https://www.revistatog.com/num3/num2.htm (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Van Lieshout, E.C.C.; van de Port, I.G.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A. Does Upper Limb Strength Play a Prominent Role in Health-Related Quality of Life in Stroke Patients Discharged from Inpatient Rehabilitation? Top Stroke Rehabil. 2020, 27, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano gallego, M.; Hernández Ferrándiz, M.; Turró Garriga, O.; Pericot Nierga, I.; López-Pousa, S.; Vilalta Franch, J. Validación del Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): Test de cribado para el deterioro cognitivo leve. Alzheimer. Real Investig. Demenc. 2009, 43, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafar, M.Z.A.A.; Miptah, H.N.; O’Caoimh, R. Cognitive Screening Instruments to Identify Vascular Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Visser, M.C.; Schouten, H.J.A.; van Gijn, J. Interobserver Agreement for the Assessment of Handicap in Stroke Patients. Stroke 1988, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrer González, B.M.; Zarco Periñán, M.J.; Ruiz de Vargas, C.E.; Docobo Durantez, F. Adaptación y validación de la escala Fugl-Meyer en el manejo de la rehabilitación de pacientes con ictus. Depósito de Investigación Universidad de Sevilla, 2015; pp. 1–189. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/40335 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Clinimetric Properties of the Timed Up and Go Test for Patients With Stroke: A Systematic Review. Topics Stroke Rehabil. 2014, 21. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kudlac, M.; Sabol, J.; Kaiser, K.; Kane, C.; Phillips, R.S. Reliability and Validity of the Berg Balance Scale in the Stroke Population: A Systematic Review. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2019, 37, 196–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzán, J.J.; Pérez del Molino, J.; Alarcón, T.; San Cristóbal, E.; Izquierdo, G.; Manzarbeitia, J. Índice de Barthel: Instrumento válido para la valoración funcional de pacientes con enfermedad cerebrovascular. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 1993, 28, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lata-Caneda, M.C.; Piñeiro-Temprano, M.; García-Fraga, I.; García-Armesto, I.; Barrueco-Egido, J.R.; Meijide-Failde, R. Spanish adaptation of the Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39). Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 45, 379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duncan, P.W.; Lai, S.M.; Bode, R.K.; Perera, S.; DeRosa, J. Stroke Impact Scale-16: A Brief Assessment of Physical Function. Neurology 2003, 60, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carod-Artal, F.J. Escalas específicas de evaluación de calidad de vida en el ictus. Neurología 2004, 39, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Lisabeth, L.; Williams, L.; Katzan, I.; Kapral, M.; Deutsch, A.; Prvu-Bettger, J. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) for Acute Stroke: Rationale, Methods and Future Directions. Stroke 2018, 49, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvermüller, F.; Berthier, M.L. Aphasia Therapy on a Neuroscience Basis. Aphasiology 2008, 22, 563–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ball, R.; Ranieri, W. Comparison of Beck depression inventories—IA and II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Personal. Assess. 1996, 67, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Chamorro, L.; Luque, A.; Dal-Re, R. Validation of the Spanish versions of the Montgomery-Asberg depression and Hamilton anxiety rating scales. Med. Clin. 2002, 118, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano García, F.J.; Rodríguez Franco, L.; García Martínez, J. Adaptación española del Inventario de estrategias de Afrontamiento. Actas. Esp. Psiquiatr. 2007, 35, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Elmståhl, S.; Malmberg, B.; Annerstedt, L. Caregiver’s Burden of Patients 3 Years after Stroke Assessed by a Novel Caregiver Burden Scale. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1996, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFOT. About Occupational Therapy. Available online: https://wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Wańkowicz, P.; Staszewski, J.; Dębiec, A.; Nowakowska-Kotas, M.; Szylińska, A.; Turoń-Skrzypińska, A.; Rotter, I. Pre-Stroke Statin Therapy Improves In-Hospital Prognosis Following Acute Ischemic Stroke Associated with Well-Controlled Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMA—The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

| Patient Evaluations | |

| Level of functional independence | BI mRS SIS-16 |

| Perceptual–cognitive skills | MoCA |

| Sensory–motor skills | FMA BBS TUG |

| Communication skills | CAL |

| Quality of life | SAQOL-39 |

| Levels of anxiety and/or depression | BDI-2 HAM-A |

| Caregiver Evaluations | |

| Caregiver burden | CBS |

| Coping strategies | CSI |

| Related to Health and Independence |

| Comorbidity Hospital readmission Subjective experience of the OT intervention Satisfaction with information provided on stroke and where to obtain support Opinion of patients and/or relatives on the adequacy of home care assistance and support ADL execution success and goals achieved Return to work Return to driving |

| Economics Data |

| Expenses related to health care Family expenses |

| Day 1: Hospital (1 h) Initial interview and evaluation. |

| Day 2: Hospital (1 h) Information about the ACV. Postural care. |

| Day 3: Housing (2 h) Study of the environment, recommendations and support products and establish individualized objectives. |

| Day 4–day 29: PHONE FOLLOW-UP. Initiation of rehabilitation by the caregiver (individual objectives). |

| Day 30: Housing (2 h). Final assessment of AVD at home. |

| At 3 months: Housing (2 h) Final evaluation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Pérez, P.; Rodríguez-Martínez, M.d.C.; Lara, J.P.; Cruz-Cosme, C.d.l. Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in the Hospital Discharge after Stroke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412877

García-Pérez P, Rodríguez-Martínez MdC, Lara JP, Cruz-Cosme Cdl. Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in the Hospital Discharge after Stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):12877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412877

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Pérez, Patricia, María del Carmen Rodríguez-Martínez, José Pablo Lara, and Carlos de la Cruz-Cosme. 2021. "Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in the Hospital Discharge after Stroke" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 12877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412877

APA StyleGarcía-Pérez, P., Rodríguez-Martínez, M. d. C., Lara, J. P., & Cruz-Cosme, C. d. l. (2021). Early Occupational Therapy Intervention in the Hospital Discharge after Stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12877. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412877