1. Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy and political populism are propelled by similar motivations: a profound distrust in elites and experts. Political influences are one of the contextual determinants of vaccine hesitancy behaviour [

1]. Kennedy [

2] found that, in 14 European countries, there was a significant association between the percentages of people in a country who voted for populist parties and of those who believed that vaccines were not important or effective. In the same way, Peretti-Watel et al. [

3] found that, in France, those who had voted for a far left or far right candidate, as well as those who abstained from voting, were much more likely to state that they would refuse vaccines. To the best of our knowledge, so far no one has studied systematically the relationship between citizen’s populist attitudes and vaccine hesitancy at an individual level in a large sample of countries. Hence, we aim to expand previous works by studying this underlying link with individual data that come from a large-scale survey that includes all the countries that belong to EU-27 + U.K. In that vein, Europe is the region with the highest level of vaccine hesitancy [

4] and populism has recently been on an upward trend [

5].

Vaccine hesitancy—the reluctance or refusal to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines—is a global issue that has become more pronounced in recent years in almost every country [

6]. One distinctive characteristic of vaccines, when compared with other medicines, is that it works both at individual and community level. Even in countries with high national vaccine uptake rates, if a population subgroup delays in acceptance or refusal of vaccines, the overall immunization strategy (at regional, national or global level) could be in danger [

1].

Achieving a quantitative knowledge of the factors associated with anti-vaccination attitudes is challenging due to the “small pockets” problem: the number of people with strong anti-vaccination attitudes represents a small minority of the population. Furthermore, any large-scale survey must be context-specific and valid. The team managing the survey, and the ulterior statistical analysis performed with the collected data, need to prove that scales are suitable in all countries and that their scores and relationships among variables could be compared. Statistically speaking, this issue is called measurement invariance.

Measurement invariance is becoming an increasingly important topic, but not yet in the vaccine hesitancy ground. In July 2021, the terms related to measurement invariance returned about 6337 hits in a Web of Science search (see

Appendix A,

Table A1 search #10). Vaccine hesitancy also attracted the interest of researchers, yielding about 5225 hits (see

Appendix A,

Table A1, search #3). For answering the question of to what extent the research about vaccine hesitancy did measurement invariance analysis, we crossed the previous queries and obtained only 2 hits (see

Appendix A,

Table A1, search #11). Main scales used for measuring vaccine hesitancy, based on scores of latent factors from multiple observed responses, are valid to the extent that the estimated parameters hold in each group under study (v.gr. country, region, etc.). Therefore, there is a gap in the scientific literature about vaccine-hesitancy.

Social marketing has been long employed in designing, implementing, and evaluating public health programs in the fight against several forms of communicable diseases [

7,

8,

9]. From the marketing perspective, audience targeting and segmentation strategy are the keys to success [

10]. To maximize vaccine uptake, better targeting is reached when based on people’s attitudes, values, and observed behaviours [

11]. For this purpose, we used invariant measures of two of the main determinants of vaccine hesitancy—distrust and usefulness of vaccines [

12]—and political populism ideas in the European citizens for determining how these variables relate to each other in EU27 + UK. Considering the average score that the interviewees in each country had in these three variables, we clustered them to obtain the different segments of European countries attending to the relationship between vaccine hesitancy and political populism. Governments and public health services (either international, national, or regional) could use these results when designing social marketing programs for overcoming hesitancy barriers associated with political populism beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours.

2. Populism and Vaccines

Political ideology influences how policymakers address and give solutions to healthcare issues [

13]. Recently, many established democracies have experienced a flourishing of populist political movements [

14]. Most of them belong to the right-wing political spectrum, but not necessarily. Hence, they do not need to share the same interests but only to fight against the same enemy (“the elite” or “the establishment”) that frustrates and endangers them all (“the people”) [

15]. The elite normally refers to mainstream political parties, the media, the upper classes, intellectuals, and, in the territorial scope of this work, the European Union [

16]. When applied to healthcare matters, medical populism [

17] is based on a distrust of evidence-based policy interventions and the condemnation of technocratic knowledge [

18,

19,

20].

Vaccine resistance fits perfectly in populist agendas. High levels of distrust and polarization are fruitful grounds for amplifying dissatisfaction with the elite [

21]. Citizen’s feelings about vaccines depend on their perceptions regarding the competence and motivation of each of the components of the vaccines value chain (v.gr., the pharmaceutical business, investigators, and health professionals), i.e., the elite, in populist terms [

22].

At the individual level, thoughts and feelings can influence getting vaccinated [

23]. Vaccine attitudes lie on a spectrum between the extremes that represent those people that have fixed anti-vaccination or pro-vaccination views [

24]. Active refusal is not the main concern for the 20 vaccines that are normally included in most of the high-income countries’ routine vaccination schedules [

25,

26]. Delaying or spreading out vaccination is a major concern [

23].

For understanding the context in which individual vaccination decisions operate, we first have to know how the actors perceive the risk involved and how it influences their behaviour. Considering the negative impact that vaccine fear has on people’s behaviour, public health experts have prioritized confidence in vaccines as a key driver in vaccination [

27,

28]. A second key component of vaccine confidence relates to trust in the social institutional system in which vaccination occurs [

29]. Citizens usually receive vaccination from a healthcare professional (physician, nurse, or pharmacist), so that trust in them seems to be a very important relationship to consider. Nevertheless, several studies showed that variation in trust of healthcare providers does not explain variation in vaccination coverage [

30,

31]. The influence of trust in vaccination behaviour must consider other social institutions that could exert more impact in the vaccination decision-process. Among them, we found the information media, the political parties, the regional or local public authorities, the national government, the national Parliament, and the European Union [

32,

33,

34,

35].

Scales for measuring attitudes toward vaccines have been usually developed for specific infectious diseases [

23]. When measuring confidence toward vaccines in general, there is evidence that a simplified scale that only considers the perceived benefits of vaccines performs as well as the entire scale [

29]. As the goal of our research is to develop a parsimonious invariant measurement model for testing the relationship between vaccine hesitancy and populism in general terms, only two drivers would be considered: the usefulness of being vaccinated (hereinafter referred as USELESS because it is reverse coded) and trust in the institutions that form the vaccine environment (hereinafter referred as DISTRUST because it is reverse coded).

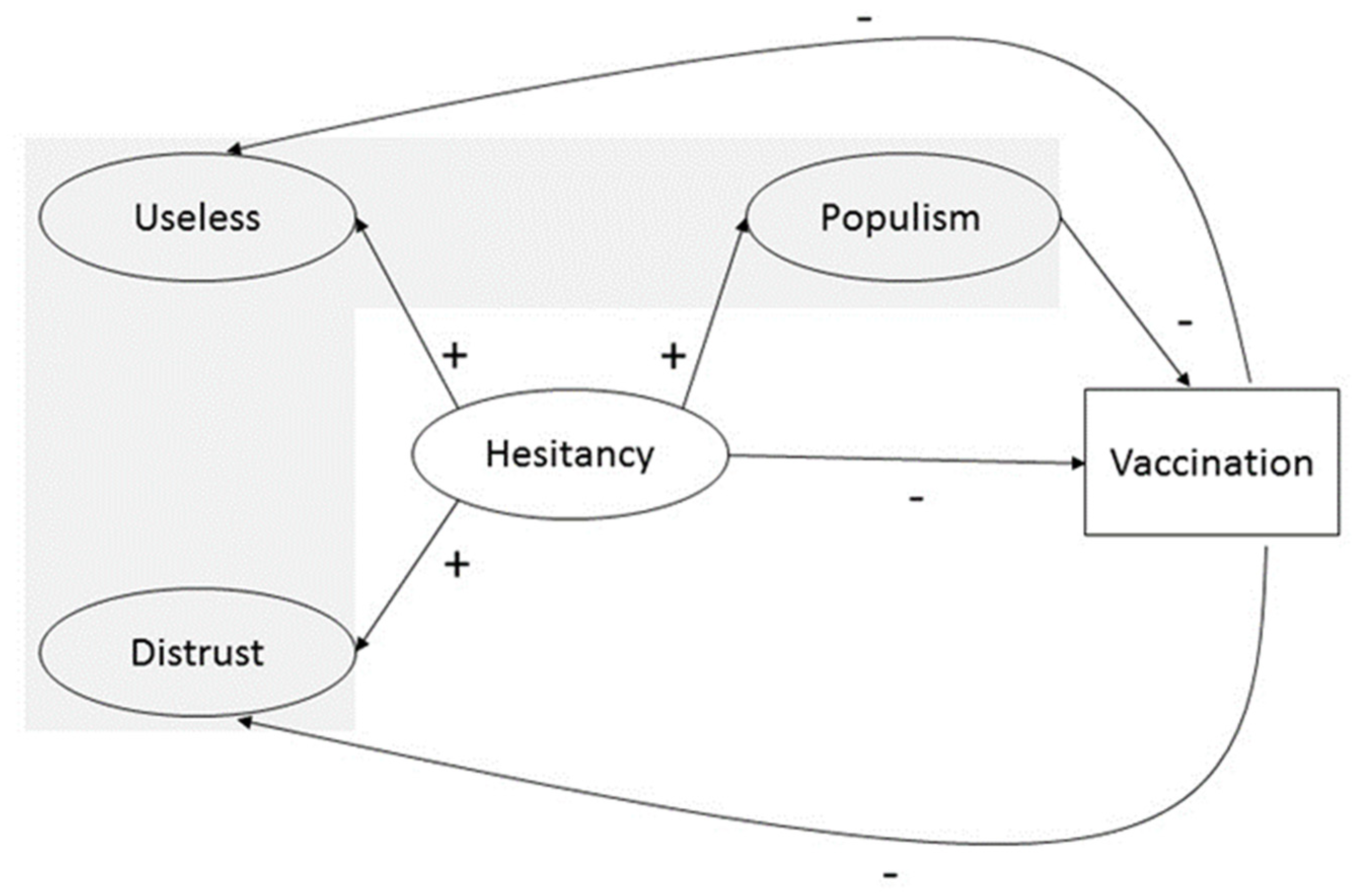

Hence, our measurement model was composed of three variables: two (USELESS and DISTRUST) that comprised vaccine-hesitancy (hereinafter referred as HESITANCY), and one that represented the politic populism (hereinafter referred as POPULISM) (see the grey-shaded area in

Figure 1). Once the measurement model proposed is stated as invariant in all countries under study, we expected that the country means for each of the latent variables would show differences among countries. We hypothesized, following Kennedy [

2], a highly positive significant association between vaccine hesitancy and political populism. We expected that the positive association between the variables would be even higher in the case of the DISTRUST-POPULISM because, as previously explained, distrust in institutions is one of the main key drivers of political populism and the nexus with vaccine hesitancy (see

Figure 2).

Hypothesis 1 (H1). USELESS, DISTRUST, and POPULISM are positively associated.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). DISTRUST and POPULISM have the highest positive association.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). POPULISM and VACCINE HESITANCY have a positive significant association across countries.

4. Results

As a first step, we checked if the hypothesized measurement model (see

Figure 2) fits well for each European country under study (separately calculated). In order to evaluate whether measurement invariance was supported, we first performed chi-square difference tests. Chi-square tests are overly sensitive when, as in our study, sample sizes are large and when the data is not normally distributed. In these cases, even substantially irrelevant differences can turn up as statistically significant [

47]. This limited the usefulness of this index in our analysis. Additionally, we considered three global fit measures: the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean residual (SRMR). We considered models with a CFI value higher than 0.90, and RMSEA and SRMR values lower than 0.08 as acceptable [

48,

49,

50]. Fit indices for all European countries met the generally accepted criteria (see

Appendix A,

Table A3).

In step two, we tested the configural invariance. This meant that we checked that each latent variable in the measurement model had the same set of indicators in each country, the model fits the data well in each country, and all factor loadings are substantial. Fit indices met the aforementioned criteria: χ

2(2828) = 7642.839,

p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.042; CFI = 0.966; SRMR = 0.052 (see

Table 1).

In step three, the fit of the model with all factor loadings constrained across the 28 European countries (metric model) was compared to the fit of the configural model. If the model fit did not significantly decrease after imposing these restrictions, the more restrictive model (metric model) could be accepted. As previously explained, the change in χ

2 was statistically significant [χ

2(3179) = 11507.306,

p = 0.000] (see

Table 1), but was not very useful because of the test’s high sensitivity to the large sample used. For that reason, we followed the suggestions made by Chen [

51] who advised considering the differences in other model fit statistics (CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR). With N > 300, differences between configural and metric models are considered relevant when the change in CFI is larger than 0.010, accompanied by a change in RMSEA larger than 0.015, or a change in SRMR larger than 0.030. The variation in RMSEA and SRMR held with the maximum 0.01 recommended, but the 0.03 variation in CFI exceeded it.

The metric and scalar models showed many large modification indices. This implied that for reaching a final good scalar model with acceptable fit indices, too many modifications were needed. Furthermore, the final result could lead us to a wrong model.

As we already mentioned in the methodological section, for overcoming the non-invariance we applied the alignment method. The advantage of the alignment method is that metric and scalar invariance are not required for comparing factor means among countries because it makes them comparable while minimizing measurement non-invariance [

44]. We ran the alignment procedure using the software MPLUS 8.6 [

45] with the country with the smallest factors mean (the Netherlands in our case) as the reference group [

52]. Results reached an overall non-invariance of 21.5% ( see

Appendix A,

Table A4). This result met the recommended rule of thumb (lower than 25% [

53]) and could be considered acceptable. Additionally, we also summarized in

Table 2 the fitting functions of both the factor loading and intercept for each item considered in the latent variables of our model. R2 values in this table corroborated these results.

For supporting the acceptance of the alignment result, we also performed Monte Carlo simulations based on the alignment parameter estimates for testing that factor means were well estimated so that countries’ comparisons could be made. In doing so, we used the number of items, the number of countries, the degree of measurement non-invariance, the country-varying factor means and variances, and the sample sizes in the countries. We carried out the analysis using MPLUS 8.6 software [

45] performing 1000 replications. In order to be trustworthy, a near-perfect correlation was required—at least 0.98—between the estimated factor means and the generated Monte Carlo ones [

38]. In our case, the correlations were USELESS = 1.000, DISTRUST = 0.999, and POPULISM = 0.998, suggesting excellent alignment despite non-invariance.

All of the previous results allowed us to feel confident in the reliability of the latent mean estimates and their comparisons across 28 countries. For better interpreting the results, the factor means for each of the 28 countries can be seen in

Figure 3 (country codes and number of respondents per country are available in

Table A2, and numerical results in

Table A5, both in

Appendix A).

For simplifying the interpretation of the results in a data-analytic way, we clustered the factor means among countries concerning their similarities. Using the factor means for each of the 28 countries obtained in the previous step, we proceeded to analyze the different country segments that existed. For choosing the best clustering method we used the package “clValid” from R [

54]. Hierarchical methods performed better than K-Means and PAM for the three internal measures of clustering validation used (Connectivity, Dunn, and Silhouette). Considering the compactness, separation, connectivity, and interpretability, the five-cluster solution performed the best.

Figure 3 visually depicts the results of the hierarchical clustering approach (using the squared Euclidean distance and the Ward method). For testing whether the country segments found were differentiable, we calculated segments’ means differences by applying an ANOVA-Tukey HSD analysis (see

Table 3). From these results, we concluded that the country segments’ mean differences were statistically significant for DISTRUST—except when comparing cluster 5 and cluster 2—and POPULISM—except when comparing clusters 5 and 3. USELESS only had statistically significant mean differences when comparing cluster 3 with any of the others.

The characteristics of each of the found segments were:

Cluster 1. The countries that belonged to this cluster were France, United Kingdom, Spain, Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia. They showed the highest mean in POPULISM, DISTRUST, and USELESS—in this latter case only surpassed by cluster 5, but not statistically significant.

Cluster 2. The countries that formed this cluster were Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. They presented a medium position in POPULISM—higher than clusters 3 and 5 and lower than clusters 1 and 4—and a medium-low position in DISTRUST—higher than cluster 3, lower than clusters 1 and 4 and not statistically significantly different from cluster 5. USELESS did not have any statistically significant difference with any other cluster.

Cluster 3. The countries that pertained to this cluster were The Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. They displayed one of the two lowest positions in POPULISM and DISTRUST—shared with cluster 5. USELESS, especially useful for marking the difference between this cluster and all the rest, presented the lowest position.

Cluster 4. The countries related to this cluster were Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Cyprus, and Malta. POPULISM and DISTRUST exhibited a medium-high level—higher than clusters 2, 3, and 5, and lower than cluster 1. The only statistically significant difference found for USELESS was that previously commented with cluster 3.

Cluster 5. The countries connected to this cluster were Austria, Luxemburg, and Ireland. As already mentioned when describing cluster 3, this cluster had the lowest positions in POPULISM and DISTRUST, tied with cluster 3, but not in USELESS, which was in line with the mean of clusters 1, 2, and 4.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

As a compulsory analytic prerequisite to making comparisons when data from large-scale surveys in several countries are used, we chose the alignment method that allowed us to check the invariance of the proposed measurement model. We reached a parsimonious invariant measurement model for studying the relationships between vaccine hesitancy and political populism in EUR 27 + UK.

From the two latent variables studied that we used for measuring vaccine hesitancy, DISTRUST had the strongest relationship with POPULISM (see

Figure 2) while USELESS was only statistically significant for differentiating cluster 3 from all the others (see

Appendix A,

Table A4). Hence, Hypotheses 1 and 2 holds.

Several European countries felt that the vaccine’s usefulness to fight against infectious diseases was not very high. Only the countries that belong to Cluster 3 (Denmark, The Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland) showed sound confidence in vaccines. For the rest of the country clusters, the perception of vaccines’ uselessness could be explained by different reasons. Some European countries that were exposed to Soviet communism (Bulgaria, Latvia, Romania, and Slovakia) depicted higher rates of vaccine USELESS ( see

Appendix A,

Table A5). Several investigations have found that weak trust in government, medical personal, and medical advice from doctors explained these cases [

55,

56,

57]. For some other eastern European countries that were also under the influence of Soviet communism (mainly the Czech Republic, Poland, and Hungary), the higher usefulness that they portrayed in vaccines could be explained by their experience developing vaccines since the 1950s and the role that they played in the propaganda campaigns claiming credit for their superiority [

58]. The rest of the ex-communist states felt, in these moments, the authoritarianism inherent in communist states when imposing vaccination trials and uptakes, which generated anti-vaccine sentiments that have remained ever since. Furthermore, not all the countries with low levels of DISTRUST and POPULISM believed that vaccines were useful for fighting against infectious diseases. As we saw, all the countries that belonged to cluster 5 (Austria, Luxembourg, and Ireland) felt that vaccines were useless. From a social marketing perspective, the results obtained for USELESS suggested that, except for countries that belonged to Cluster 3, marketing actions needed to be implemented to reinforce the association of vaccines as a proven and successful solution to fight against infectious diseases.

Distrust in institutions was the main underlying driver that was associated with both vaccine hesitancy and political populism (see

Figure 2). We also saw (

Figure 3) that a positive relationship existed between the two variables that formed vaccine hesitancy (USELESS and DISTRUST) and POPULISM. Hence, Hypothesis 3 also holds.

The challenge that the world seems to be facing is trustdemic: falling public trust is all around the world [

59,

60,

61]. This could explain how vaccine-hesitancy is increasing worldwide while having highly effective vaccines. Trusted institutions are the grease in the social machine. As Khanna [

62] said, “When citizens lack trust, they are less likely to comply with laws and regulations, pay taxes, tolerate different viewpoints or ways of life, contribute to economic vitality, resist the appeals of demagogues, or support their neighbours. Without trust, societies are at risk of chaos and conflict.”

Populist political parties know that vaccines are fertile ground for instilling doubt and trying to gain from polarized debates [

63]. The main strategy of populists is to polarize pro and con views on vaccines, joining them with any other sentiments (anti-chemical, anti-science, anti-migration, anti-abort, anti-government, etc.) [

64]. Results from this strategy were clear: our measurement model portrayed a strong positive relationship among DISTRUST and POPULISM in all the European countries.

Vaccine-hesitancy is also very adequate for the populism strategy due to the “small pockets” issue. They do not need to convince the whole population to follow a vaccine-hesitant attitude. “Herd immunity”, the level at which immunization coverage has to be maintained in order to be effective, depends on the vaccine but it typically ranges between 80% and 90% of the population [

23,

65]. Hence, a small number of vaccine-hesitants can have enormous adverse effects on herd immunity and epidemic spread. Even more, if we consider that this low percentage that is leftover to attain “herd immunity” has to be reserved for people with compromised immune systems or for those that are too young, for example, neonates.

We also must bear in mind that to be vaccine-hesitant does not necessarily imply that one does not take any vaccines. Willingness to be vaccinated lies in a continuum ranging from those who accept all vaccines without any doubt to those who reject all without any doubt. It is complex and context-specific, varies across time, place, and vaccines [

65,

66]. Therefore, from the willingness to be vaccinated to the uptake there is still a myriad of factors that could influence the final decision and that belong to the demand side of vaccination [

8,

67]. One of them could be how populism affects vaccination uptake. It has not been studied in this paper. The mediation role of populism on vaccine uptake, depicted in

Figure 1, is part of an ongoing research study that has obtained promising preliminary results.

From the results, there are several implications for management. First, sixteen out of twenty-eight European countries under study showed high rates of distrust in institutions and populism and medium-low levels of confidence in vaccines for fighting against infectious diseases. They are all the countries that belong to Cluster 1 and Cluster 4. Populist organizations likely take advantage of this situation for generating social instability based on vaccine-hesitancy. Second, having low levels of distrust and populism does not mean living without problems. Countries that compose Cluster 3 have the highest perception that vaccines are not useful. Hence, vaccine hesitancy could be high and populist organizations could profit from this situation. Third, countries that constitute cluster 3 are at the medium of the spectrum. The two countries that belonged to the former Soviet communism area of influence (Hungary and Czech Republic) are proud of the role played during the Cold War when developing vaccines. Nevertheless, the economic, political, and economic situation in these countries could make them follow the same path as Poland (also proud of their vaccine experience in the past, but with higher levels of distrust and populism). Germany shares a similar problem: the

landers that were in the Soviet communism area of influence have higher degrees of vaccine hesitancy and populist organizations are making use of it [

68]. Fourth, countries included in Cluster 3 portray the best position represented by the low rates of the three drivers. Nevertheless, the “small pockets” concern could be a problem in these countries due to the existence of global vaccine-hesitant segments [

69].

Social marketing must be targeted for convincing vaccine-hesitants that to be vaccinated is a societal health strategy and not just a question about individual rights. Proactive steps must be implemented for restoring the trust in scientists that develop vaccines, governments, institutions, and businesses. A lifetime acceptance of vaccine programs, orchestrated through a relationship marketing campaign, could be the basis of a trust chain for better resisting the negative economic and social outcomes derived from the association that this paper shows between populism and vaccine-hesitancy.